Abstract

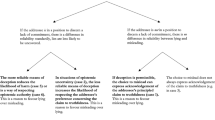

Lying is standardly distinguished from misleading according to how a disbelieved proposition is conveyed. To lie, a speaker uses a sentence to say a proposition she does not believe. A speaker merely misleads by using a sentence to somehow convey but not say a disbelieved proposition. Front-and-center to the lying/misleading distinction is a conception of what-is-said by a sentence in a context. Stokke (Philos Rev 125(1):83–134, 2016, Lying and insincerity, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2018) has recently argued that the standard account of lying/misleading is explanatorily inadequate unless paired with a theory where what-is-said by a sentence is determined by the question under discussion or qud. I present two objections to his theory, and conclude that no extant theory of what-is-said enables the standard account of the lying/misleading distinction to be explanatorily adequate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Saul (2012, 56–57) surprisingly suggests that the theories of King and Stanley (2005), Bach (2002), and Carston (2002) are all compatible with nte. One may wonder, as a referee does, whether this is the correct classification of Bach and Carston. Since neither of their views fall within this paper’s focus, I do not take a stance on classification.

Stokke (2016, 2018) is not the first to suggest that sentences can express a cloud of propositions. See Poesio (1996), Braun and Sider (2007), von Fintel and Gillies (2009), Saul (2012), and King (2018) for similar proposals and further discussion of how underspecified declaratives express many propositions.

This definition differs from the earlier definition found in Stokke (2016, 104) by making the second condition disjunctive. It previously required only that p\(\subseteq\)\(\mu _{c }\)(S). Allowing \(\mu _{c }\)(S) \(\subseteq\)p enables the view to explain what happens with downward entailing operators. See Stokke (2018, 101–102) for discussion.

In a previous version of this paper, I suggested that (5b) might be elliptical for Doris lost her job because Doris insulated Sean at a party while (6b) was not. Were this so, a \({\textsc {wis}}_{\textsc {nte}}\) theory could enable \({\textsc {sa}}_{\textsc {l/m}}\) to identify William’s reply as a lie. I now regard this suggestion as misguided. As my referees pointed out, no extant proposal of syntactic ellipsis will predict as much. Were (5b) a fragment like Because Doris insulted Sean at a party, matters would be different because the connective because is stranded. But (5b) is not a fragment.

Examples of helpful non-answers abound. Here is a variant of (7b). With or without well, pronounce Doris insulted Sean at a party with a fall-rise intonational contour conveying uncertainty (Ward and Hirschberg 1985; Constant 2012). The contour does not contributes to a sentence’s truth-conditions like well, and it yields the same effect as (7b). However, I focus on (7b) because the semantics of intonation is complicated enough to create unnecessary noise in counterexamples.

Relatedly, William can produce the discourse Well, Doris did insult Sean at a party. But I don’t know that Doris lost her job because she insulted Sean without producing Moorean absurdity. But the discourse would be absurd if the first sentence said that Doris lost her job because she insulted Sean at a party.

A referee wonders if helpful non-answers are not assertions. Then condition (ii) of sl for being a lie would not be met. As a consequence, no mistaken predictions would be made by pairing \({\textsc {sa}}_{\textsc {l/m}}\) with sl and \({\textsc {wis}}_{\textsc {qud}}\). But helpful non-answers bear all the tell-tale signs. An assertion on the Stalnakerian conception adopted by Stokke is a proposal to update the common ground with a proposition (Sect. 2). A reply like (7b) is exactly that. It is a proposal to update the common ground with the proposition that Doris insulted Sean at a party. It is just not also offered as an answer to the prior question, which is why it is mishandled. Another sign that a reply like (7b) is an assertion is that it can be extended into a Moorean absurdity. Witness the defectiveness of Well, Doris did insult Sean at a party, but I don’t know that she did. Both features of (7b) make it starkly contrast with a sentence like Doris insulted Sean at a party, I heard. Such a hedged reply also does not seem to say that Doris lost her job because she insulted Sean at a party. But it is plausibly not an assertion because it is neither a proposal to update the common ground nor extendible into a discourse that is absurd. For more on hedged assertion, see Benton and van Elswyk (2018).

In any case, the pull-back proposal is incompatible with the alternative view. By having what-is-said by a sentence like (9b) be a generalized proposition, whether the super liar is lying or sincere is no longer indeterminate. They are speaking sincerely because the generalized proposition is believed.

It is important to hold to the earlier stipulation that (10a) through (10c) are the only candidate relations my could specify in the context. If it helps, assume that it is common ground between Norma and Larry that Larry only traffics in books when he is writing them, checking them out from the library, or reading them for book club. If we drop this stipulation, Larry can rely on a way of being related to a book of which Norma is unaware. Were Norma to follow-up to (13d) with What do you mean?, Larry could give an answer even if it strained credibility. But, given the stipulation, Larry lacks an answer to that follow-up. He is limited to one of three options and he denied all three in (13d). Therein lies his lack of plausible deniability. Thanks are owed to a referee for helping me see the importance of this stipulation.

A qud-based approach to discourse structure is appealed to in explanations of a wide range of phenomena across philosophy and linguistics. Examples include ellipsis, focus, indefinites, knowledge ascriptions á la epistemic contextualism, presupposition projection, discourse particles, and appositives. For many, hanging onto the qud will be a compelling reason to pursue this first option. Skeptics of the qud will be less compelled. I count myself among the skeptics.

\({\textsc {wis}}_{\textsc {qud}}\) contrasts strongly with other non-\({\textsc {wis}}_{\textsc {nte}}\) theories intended to predict enrichment. For example, Relevance Theory, as developed by Sperber and Wilson (1986), relies on principles of communication not precise enough to generate predictions. See Bach (2010) and Pagin (2014) for discussion.

References

Adler, J. (1997). Lying, deceiving, or falsely implicating. Journal of Philosophy, 94(9), 435–452.

Asher, N., & Lascarides, A. (2003). Logics of conversation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bach, K. (2002). Seemingly semantic intuitions. In J. C. Keim, M. O’Rourke, & D. Shier (Eds.), Meaning and truth (pp. 21–33). New York: Seven Bridges.

Bach, K. (2010). Impliciture vs explicature: What’s the difference? In B. Soria & E. Romero (Eds.), Explicit communication: Robyn Carston’s pragmatics (pp. 126–137). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Benton, M., & van Elswyk, P. (2018). Hedged assertion. In S. Goldberg (Ed.), Oxford handbook of assertion. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Braun, D., & Sider, T. (2007). Vague, so untrue. Nous, 41(2), 133–156.

Cappelen, H., & Lepore, E. (2005). Insensitive semantics. Oxford: Blackwell.

Carlson, L. (1984). ‘Well’ in Dialogue Games: A discourse analysis of the interjection ‘well’ in idealized conversation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Carston, R. (2002). Thoughts and utterances: The pragmatics of explicit communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Constant, N. (2012). English rise-fall-rise: A study in the semantics and pragmatics of intonation. Linguistics and Philosophy, 35(5), 407–442.

Hamblin, C. L. (1973). Questions in montague english. Foundations of Language, 10(1), 41–53.

Kehler, A. (2002). Coherence, reference, and the theory of grammar. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

King, J. C. (2018). Strong contextual felicity and felicitous underspecification. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 97, 631–657.

King, J. C., & Stanley, J. (2005). Semantics, pragmatics and the role of semantic content. In Z. Szabó (Ed.), Semantics versus pragmatics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lakoff, R. (1973). Questionable answers and answerable questions. In B. Kachru (Ed.), Papers in honor of Henry and Renee Kahane (pp. 453–467). Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

Martin, J. (1992). English text: System and structure. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Owens, M. L. (1983). Apologies and remedial interchanges. Paris: Mouton.

Pagin, P. (2014). Pragmatic enrichment as coherence raising. Philosophical Studies, 168(1), 59–100.

Poesio, M. (1996). Semantic ambiguity and perceived ambiguity. In K. van Deemter & S. Peters (Eds.), Semantic ambiguity and underspecification (pp. 159–201). Stanford: CSLI.

Pomerantz, A. (1984). Agreeing and disagreeing with assessments: some features of preferred/dispreferred turn shapes. In J. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis (pp. 57–101). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Roberts, C. (1996/2012). Information structure in discourse: Towards an integrated formal theory of pragmatics. Semantics and Pragmatics, 6, 1–69.

Saul, J. (2012). Lying, misleading, and what is said: An exploration in philosophy of language and in ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schiffrin, D. (1987). Discourse markers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schoubye, A., & Stokke, A. (2016). What is said? Nous, 50(4), 759–793.

Searle, J. (1978). Literal meaning. Erkenntnis, 13, 207–224.

Sperber, D., & Wilson, D. (1986). Relevance. Oxford: Blackwell.

Stalnaker, R. (1978). Assertion. Syntax and semantics 9: Pragmatics (pp. 315–332). Cambridge: Academic Press.

Stalnaker, R. (2002). Common ground. Linguistics and Philosophy, 25(5–6), 701–721.

Stojnic, U., Stone, M., & Lepore, E. (2017). Discourse and logical form: Pronouns, attention, and coherence. Linguistics and Philosophy, 40(5), 519–547.

Stokke, A. (2013). Lying and asserting. Journal of Philosophy, 110(1), 33–60.

Stokke, A. (2016). Lying and misleading in discourse. Philosophical Review, 125(1), 83–134.

Stokke, A. (2018). Lying and insincerity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Travis, C. (1996). Meaning’s role in truth. Mind, 100, 451–466.

von Fintel, K., & Gillies, T. (2009). ‘Might’ made right. In A. Egan & B. Weatherson (Eds.), Epistemic modality, chapter ‘Might’ made right. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ward, G., & Hirschberg, J. (1985). Implicating uncertainty: The pragmatics of fall-rise intonation. Language, 61(4), 746–776.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are owed to Liz Camp, Chris Willard-Kyle, Jeff King, Nico Kirk-Giannini, Carolina Flores, Joshua Spencer, and two referees for helpful comments or conversation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van Elswyk, P. Deceiving without answering. Philos Stud 177, 1157–1173 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-019-01239-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-019-01239-7