Abstract

Purpose

Since the introduction of the molecular definition of oligodendrogliomas based on isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH)-status and the 1p19q-codeletion, it has become increasingly evident how this glioma entity differs much from other diffuse lower grade gliomas and stands out with longer survival and often better responsiveness to adjuvant therapy. Therefore, apart from using a molecular oligodendroglioma definition, an extended follow-up time is necessary to understand the nature of this slow growing, yet malignant condition. The aim of this study was to describe the long-term course of the oligodendroglioma disease in a population-based setting and to determine which factors affect outcome in terms of survival.

Methods

All adults with WHO-grade 2 oligodendrogliomas with known 1p19q-codeletion from five Scandinavian neurosurgical centers and with a follow-up time exceeding 5 years, were analyzed regarding survival and factors potentially affecting survival.

Results

126 patients diagnosed between 1998 and 2016 were identified. The median follow-up was 12.0 years, and the median survival was 17.8 years (95% CI 16.0–19.6).

Factors associated with shorter survival in multivariable analysis were age (HR 1.05 per year; CI 1.02–1.08, p < 0.001), tumor diameter (HR 1.05 per millimeter; CI 1.02–1.08, p < 0.001) and poor preoperative functional status (KPS < 80) (HR 4.47; CI 1.70–11.78, p = 0.002). In our material, surgical strategy was not associated with survival.

Conclusion

Individuals with molecularly defined oligodendrogliomas demonstrate long survival, also in a population-based setting. This is important to consider for optimal timing of therapies that may cause long-term side effects. Advanced age, large tumors and poor function before surgery are predictors of shorter survival.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oligodendrogliomas are usually slow-growing primary CNS tumors that often give rise to first-time seizures in young to middle-aged adults. The tumors are classified as diffuse lower grade gliomas (LGG) together with isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH)-mutated astrocytomas [1]. The tradition for treating oligodendrogliomas and astrocytomas together in the scientific literature is, however, likely to have blurred important differences between the respective subgroups.

The advent of molecular definitions in tumor classification has allowed clear demarcations between subtypes and elucidated important differences in anatomical preferential locations, clinical course, treatment responses and prognosis. For oligodendrogliomas, predictors for an unfavorable clinical course are particularly at risk for being concealed in merged analyses due to dominant effects from tumor subtypes with shorter time to event, such as astrocytomas and IDH-wildtype (IDH-wt) LGG, all being part of older LGG cohorts [2]. Another shortcoming, common to most publications with molecular data, is that the follow-up time of patients with oligodendrogliomas is too short to adequately assess survival [2, 3]. Surrogate markers for survival such as "progression free survival" (PFS) have been used to circumvent this problem, but the correlation between PFS and actual survival may be very weak [4,5,6,7,8]. Since oligodendrogliomas are rare tumors, large cohorts with detailed individual level data are needed but still few [9]. Other studies with relative long follow-up may reflect the clinical course for patients selected for surgery in specialized centers [7, 10].

To address these difficulties, we performed a long-term multicenter study including only patients with molecularly defined grade 2 oligodendrogliomas, with the aim to describe the course of the disease and to determine prognostics in a population-based context.

Materials and methods

Study population

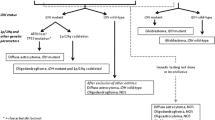

All adults (aged 18 or above) with a known 1p19q-codeleted oligodendroglioma WHO grade 2 diagnosis and with a minimum follow-up time of 5 years (for non-deceased patients), were included from five Scandinavian neurosurgical centers with inclusion periods between 1998 and 2016 (N = 126). Cases were retrieved from histopathological records of WHO grade 2 tumors with inclusion periods differing for the different centers but in all cases with a minimal follow-up period of 5 years and with a common end of studydate, January 1:st 2021. For details see Fig. 1. All centers serve defined geographical areas, which is why the material reflects an unselected oligodendroglioma patient population.

Data collection

Medical records and radiological images were used to identify patient-, tumor-, and treatment characteristics. Tumor localization was defined as the cerebral lobe mainly affected. Cases with more than one lobe clearly affected were classified as multi-lobar. Eloquent tumor location was described according to Sawaya [11]. Largest diameter referred to the largest diameter in MRI measured either in the axial, coronal or sagittal plane. Regarding initial surgical strategy, patients that were initially biopsied but resected within the first 3 months after biopsy, were defined as resected. Patients never resected or resected after more than 3 months after biopsy were classified as biopsied regarding initial surgical strategy. All tumors were histopathologically identified as low grade gliomas and molecularly defined through low-grade glioma related research, or in more recent years, IDH and 1p19q status were detected according to clinical practice in the respective institutions. IDH-mutation status was evaluated with immunohistochemistry for R132H, and sequencing was used in selected cases [12]. For 1p19q detection we accepted fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) and methylation analysis as described earlier [12, 13]. All cases were 1p19q-codeleted, but 20 tumors were lacking data on IDH mutational status, whereas two cases were assigned to the oligodendroglioma group based upon detection of 1p19q-codeletion in the absence of detected IDH-mutations.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were done with SPSS, version 28 or newer (Chicago, IL, USA) or R [version 4.2.2 GUI 1.79 High Sierra build (8160)] and R studio (version 2022.12.0 + 353). Statistical significance level was set to p < 0.05. All tests were two-sided. Central tendencies are presented as means ± SD, or median with first and third quartile if skewed. Overall survival and median follow-up time were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method. Uni- and multivariable Cox regression analyses were performed for survival. Assumptions for proportional hazards were verified. For the multivariable analysis, variables were chosen by perceived clinical relevance and statistical significance in the unadjusted analysis. To avoid overloading the model, only variables associated at the p < 0.05 level in the unadjusted analyses were entered into the multivariable regression model. However, in a sensitivity analysis, also variables associated at the p < 0.1 were used for a separate multivariable model.

Kaplan–Meier curves with log rank tests were used for visualization of findings in survival analyses. Spearman´s rank correlation was used to check correlations between continuous covariates, independent t-test and Mann–Whitney U-test were used to check correlations between categorical variables and covariates when normally distributed and non-parametrically distributed respectively.

Results

In total 126 patients were included with a median follow-up of 12.0 (CI 11.1–12.8) years (reversed Kaplan–Meier method). The median age at inclusion was 42.5 years, ranging from 20 to 78. The preoperative patient characteristics, tumor data and treatment variables are presented in Table 1.

As shown in Table 1, the cohort was heterogeneously treated; 24 patients (19.0%) had early chemotherapy, 45 patients (35.7%) had early radiotherapy, whereas 10 patients (7.9%) had both radio-and chemotherapy within 6 months. All patients but 15 (11.9%) underwent resective surgery at some point during the follow-up-period.

Survival

The median survival time was 17.8 years (Fig. 2).

Predictors for survival

In Cox regression analysis, factors affecting survival were examined (Table 2).

In univariable analyses, the parameters increased age, impaired functional status (KPS < 80), preoperative neurological deficit, tumor crossing the midline of the brain and larger tumor diameter, were correlated with reduced survival. In adjusted analysis, only increased age (HR 1.05; CI 1.02–1.08, p < 0.001), larger tumor diameter (HR 1.05; CI 1.02–1.08, p < 0.001) and KPS < 80 (HR 4.47; CI 1.70–11.78, p = 0.002) remained associated with shorter survival. A sensitivity analysis including all variables associated with survival at a p < 0.1 level did not change the results (Supplementary Table S1), nor did a corresponding multivariable model that also included "initial surgical strategy" (data not shown).

Kaplan–Meier curves are presented for age and tumor size strata to illustrate findings visually (Fig. 3).

There was no statistically significant correlation between age and tumor size (Spearman’s rho = 0.13, p = 0.16). Nor was the difference in median age and mean tumor size significant for patients with KPS < 80 compared to those with KPS ≥ 80 (age 51.0 vs. 42.0 years, p = 0.50, tumor diameter 63.6 vs. 55.8 mm, p = 0.20).

Sub-analyses were made assessing early chemo- and radiotherapy in groups stratified by risk (Supplementary Fig. S1). In the low-risk stratum (age < 45 and tumor size < 50 mm) there were only three events (n = 28). In the high-risk group (age ≥ 45 and tumor size ≥ 50 mm) (n = 97), there was no statistically significant difference in survival comparing early chemo- or radiotherapy with delayed or absent such therapy (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Discussion

In this population based multi-center observational study with long-term data of WHO grade 2 oligodendrogliomas, the median survival was almost 18 years. During this long follow-up, patients were heterogeneously treated, and most patients underwent multiple treatment interventions. Only increased age, larger tumor diameter and KPS < 80 correlated with impaired survival in multivariable analyses.

Baseline characteristics

In line with previous studies of oligodendrogliomas, the patients in the present cohort were somewhat older at diagnosis than what is typically reported for LGG cohorts that include a mixture of IDH-mutated astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas. Also, more males than females were affected, the vast majority had seizures preoperatively, and the tumors had a predilection for frontal lobe engagement [10, 14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. We believe that this congruence with earlier observations supports the external validity of the present study.

Prognostic factors

As seen in our results, and as previously known from earlier studies with molecularly defined oligodendrogliomas, the survival times clearly exceed those of other diffuse gliomas [10, 17, 21, 22]. Publications on oligodendrogliomas lacking molecular data have probably been subjected to considerable misclassification and therefore also to confounding effects from IDH-wt tumors and IDH-mut astrocytomas [23,24,25]. More recent publications with separate analyses for the different molecular tumor subtypes, on the other hand, are often disadvantaged by short follow-up times in relation to the expected survival time [10, 14, 16,17,18, 23, 26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35].

Bearing these limitations in mind, the present study together with several earlier studies identify older age as a predictor for poor survival also in molecularly defined cohorts [23, 28, 33, 35,36,37]. The correlation was however not reported in another recent large cohort study [10]. Since higher age is associated with shorter survival also among healthy individuals and the median survival in our cohort is nearly 18 years, some patients may of course have died from unrelated causes.

Studies on 1p19q-codeleted tumors presenting data on pre-operative tumor size have almost consequently shown a correlation between larger tumor size and worse prognosis [10, 14, 17, 19, 34, 36, 38]. Nevertheless, in a large registry based study by Garton et al. no significant correlation was seen between tumor size and survival [23]. This conflicting result might derive from the potentially less reliable size data in the registry of the mentioned study.

The shorter survival associated with impaired performance status (KPS < 80) seen in the current work is unsurprising and confirms earlier studies, even if it is not entirely clear whether it stands for advanced disease or serious co-morbidities that were not adjusted for [7, 28].

Initial surgical strategy (biopsy vs. resection) did not significantly affect survival in the present study. The strong correlation between Extent of resection (EOR)/Gross total resection (GTR) and survival often found in studies involving astrocytomas, seems to be less apparent (even if sometimes present) for patients with 1p19q-codeleted oligodendrogliomas [7, 10, 14, 17, 19, 26, 28, 29, 32, 39], although contrary results do exist [16].

There are also several oligodendroglioma studies with data from large American cancer registries (National Cancer Database/NCBD and SEER/Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results) that have shown correlations between GTR and prolonged survival when compared to biopsy/no surgery [34, 35], especially in anaplastic oligodendrogliomas [23]. Conflicting results particularly for the role of subtotal resections (STR) among these studies, and in relation to other studies based on the same registries, have been reported, possibly due partly to different interpretations of the codes used for extent of resection [23, 29, 34, 35, 40, 41]. The less prominent effect of surgical resection in oligodendrogliomas may be due to data immaturity, since, in many studies, the number of events may come in single digits for the oligodendroglioma subgroup [17, 18, 27, 31] or reflect only the first few years in a disease course expected to last for almost two decades [14, 29, 33]. It could also be that these tumors are more responsive to other treatment, affecting the overall surgical impact [21]. Also, in observational data with long follow-ups, patients may undergo multiple interventions at various time points, making it difficult to isolate effects of single treatment elements. Further, in studies like ours, that lack volumetric data, a therapeutic effect of surgery may not emerge as clearly as in those with quantified residual tumor volumes, where an assumed dose response relationship would be possible to detect. In the present study, the category "resection" includes surgeries with any attempt of debulking surgery as well as complete resections due to lack of postoperative imaging in the earlier time-periods. Nevertheless, in a recent study by Hervey-Jumper et al. [10] the association between residual tumor volume and survival was clear but not independent from preoperative tumor volume in molecularly defined oligodendrogliomas (unlike the case for astrocytomas). Despite long follow-up, data immaturity was a concern also in this publication [10], making conclusions difficult to draw when only 16.3% (31/190) of the patients with oligodendrogliomas were deceased in the largest cohort with the longest follow-up.

For WHO grade 3, 1p19q-oligodendrogliomas, an interesting publication by Garnier et al. specifically addressed short-time survivors (cancer specific survival less than 5 years) [36]. These patients differed in several ways from the classical survivors and were for example older (median age 57.4), more often presented with symptoms other than only seizures, were more often biopsied, and had a larger preoperative tumor volume (mean 186 cm3). Almost all the clinical factors characterizing the short-time-survivors of this study, were also found as predictors for impaired survival in the present study, at least in univariable analysis (age, large tumor size, impaired cognition/neurological deficit, engagement of midline structures).

We believe that the long survival times demonstrated in this publication are important to consider when deciding on the best timing of treatment in relation to the risk profile [42,43,44,45].

For example, high risk resections or early radiotherapy should be weighed up against the relatively long survival on group level, thus allowing for multiple reinterventions if needed later, postponing the risk for sequelae. However, the identified risk factors for shorter survival may be useful in decision making when considering pros and cons of different treatment options.

Limitations

The study is subject to all limitations inherent to a retrospective observational study including the inability to conclude causality from detected associations. As most patients underwent multiple interventions, the results should not be confused with the natural course of the disease. Also, the sample size of 126 patients, although one of the larger cohorts in the context of molecularly defined cases with individual level data, is limited. Similarly, and as mentioned before, the median follow-up of 12 years may, even though probably longer than in any other molecular study, still be regarded as too short, considering the expected longevity of the analyzed cohort. Finally, volumetric data on tumor residuals would have increased the resolution with which the effect of surgery could be evaluated.

Conclusion

This long-term study of patient with heterogeneously treated 1p19q-codeleted oligodendroglioma WHO grade 2 demonstrates that the median survival approaches 20 years in a population-based setting. Further, increased patient age, lower functional status and larger preoperative tumor size were independently associated with impaired survival. Altogether, these findings may be used to weigh risks and benefits of treatment, especially considering potential long-term risks of early treatment.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of the present study are not publicly available, due to them containing information that could compromise research participant privacy/consent. The data are however available upon reasonable request to the authors.

References

Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P et al (2021) The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Neuro Oncol 23(8):1231–1251. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/noab106

Rincon-Torroella J, Rakovec M, Materi J et al (2022) Current and future frontiers of molecularly defined oligodendrogliomas. Front Oncol 12:934426. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.934426

Albuquerque LAF, Almeida JP, de Macêdo Filho LJM, Joaquim AF, Duffau H (2021) Extent of resection in diffuse low-grade gliomas and the role of tumor molecular signature—a systematic review of the literature. Neurosurg Rev 44(3):1371–1389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-020-01362-8

Booth CM, Eisenhauer EA (2012) Progression-free survival: Meaningful or simply measurable? J Clin Oncol 30(10):1030–1033. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2011.38.7571

Gyawali B, Eisenhauer E, Tregear M, Booth CM (2022) Progression-free survival: it is time for a new name. Lancet Oncol 23(3):328–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(22)00015-8

Gilbert MR, Dignam JJ, Armstrong TS et al (2014) A randomized trial of bevacizumab for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 370(8):699–708. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1308573

Mair MJ, Geurts M, van den Bent MJ, Berghoff AS (2021) A basic review on systemic treatment options in WHO grade II–III gliomas. Cancer Treat Rev 92:10224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2020.102124

Scherer M, Ahmeti H, Roder C et al (2020) Surgery for diffuse WHO Grade II gliomas: volumetric analysis of a multicenter retrospective cohort from the German study group for intraoperative magnetic resonance imaging. Neurosurgery 86(1):E64-e74. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuros/nyz397

Achey RL, Khanna V, Ostrom QT, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS (2017) Incidence and survival trends in oligodendrogliomas and anaplastic oligodendrogliomas in the United States from 2000 to 2013: a CBTRUS Report. J Neurooncol 133(1):17–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-017-2414-z

Hervey-Jumper SL, Zhang Y, Phillips JJ et al (2023) Interactive effects of molecular, therapeutic, and patient factors on outcome of diffuse low-grade glioma. J Clin Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.21.02929

Sawaya R, Hammoud M, Schoppa D et al (1998) Neurosurgical outcomes in a modern series of 400 craniotomies for treatment of parenchymal tumors. Neurosurgery 42(5):1044–1055. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006123-199805000-00054 (Discussion 1055–6)

Jakola AS, Skjulsvik AJ, Myrmel KS et al (2017) Surgical resection versus watchful waiting in low-grade gliomas. Ann Oncol 28(8):1942–1948. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx230

Ferreyra Vega S, Olsson Bontell T, Corell A, Smits A, Jakola AS, Carén H (2021) DNA methylation profiling for molecular classification of adult diffuse lower-grade gliomas. Clin Epigenetics 13(1):102. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13148-021-01085-7

Carstam L, Corell A, Smits A et al (2021) WHO grade loses its prognostic value in molecularly defined diffuse lower-grade gliomas. Front Oncol 11:803975. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.803975

Carstam L, Rydén I, Jakola AS (2022) Seizures in patients with IDH-mutated lower grade gliomas. J Neurooncol 160(2):403–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-022-04158-6

Aoki K, Nakamura H, Suzuki H et al (2018) Prognostic relevance of genetic alterations in diffuse lower-grade gliomas. Neuro Oncol 20(1):66–77. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nox132

Kavouridis VK, Boaro A, Dorr J et al (2019) Contemporary assessment of extent of resection in molecularly defined categories of diffuse low-grade glioma: a volumetric analysis. J Neurosurg. https://doi.org/10.3171/2019.6.Jns19972

Bush NAO, Young JS, Zhang Y et al (2021) A single institution retrospective analysis on survival based on treatment paradigms for patients with anaplastic oligodendroglioma. J Neurooncol 153(3):447–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-021-03781-z

Latini F, Fahlström M, Hesselager G, Zetterling M, Ryttlefors M (2020) Differences in the preferential location and invasiveness of diffuse low-grade gliomas and their impact on outcome. Cancer Med 9(15):5446–5458. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.3216

Skjulsvik AJ, Bø HK, Jakola AS et al (2020) Is the anatomical distribution of low-grade gliomas linked to regions of gliogenesis? J Neurooncol 147(1):147–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-020-03409-8

Cairncross JG, Ueki K, Zlatescu MC et al (1998) Specific genetic predictors of chemotherapeutic response and survival in patients with anaplastic oligodendrogliomas. J Natl Cancer Inst 90(19):1473–1479. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/90.19.1473

Wesseling P, van den Bent M, Perry A (2015) Oligodendroglioma: pathology, molecular mechanisms and markers. Acta Neuropathol 129(6):809–827. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-015-1424-1

Garton ALA, Kinslow CJ, Rae AI et al (2020) Extent of resection, molecular signature, and survival in 1p19q-codeleted gliomas. J Neurosurg 134(5):1357–1367. https://doi.org/10.3171/2020.2.Jns192767

Iorgulescu JB, Torre M, Harary M et al (2019) The misclassification of diffuse gliomas: rates and outcomes. Clin Cancer Res 25(8):2656–2663. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-18-3101

Brat DJ, Verhaak RG, Aldape KD et al (2015) Comprehensive, integrative genomic analysis of diffuse lower-grade gliomas. N Engl J Med 372(26):2481–2498. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1402121

Delev D, Heiland DH, Franco P et al (2019) Surgical management of lower-grade glioma in the spotlight of the 2016 WHO classification system. J Neurooncol 141(1):223–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-018-03030-w

Kawaguchi T, Sonoda Y, Shibahara I et al (2016) Impact of gross total resection in patients with WHO grade III glioma harboring the IDH 1/2 mutation without the 1p/19q co-deletion. J Neurooncol 129(3):505–514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-016-2201-2

Lin AJ, Kane LT, Molitoris JK et al (2020) A multi-institutional analysis of clinical outcomes and patterns of care of 1p/19q codeleted oligodendrogliomas treated with adjuvant or salvage radiation therapy. J Neurooncol 146(1):121–130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-019-03344-3

Lu VM, Alvi MA, Bydon M, Quinones-Hinojosa A, Chaichana KL (2019) Impact of 1p/19q codeletion status on extent of resection in WHO grade II glioma: insights from a national cancer registry. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 182:32–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2019.04.027

Patel SH, Bansal AG, Young EB et al (2019) Extent of surgical resection in lower-grade gliomas: differential impact based on molecular subtype. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 40(7):1149–1155. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A6102

Weller J, Katzendobler S, Karschnia P et al (2021) PCV chemotherapy alone for WHO grade 2 oligodendroglioma: prolonged disease control with low risk of malignant progression. J Neurooncol 153(2):283–291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-021-03765-z

Wijnenga MMJ, French PJ, Dubbink HJ et al (2018) The impact of surgery in molecularly defined low-grade glioma: an integrated clinical, radiological, and molecular analysis. Neuro Oncol 20(1):103–112. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nox176

Yeboa DN, Yu JB, Liao E et al (2019) Differences in patterns of care and outcomes between grade II and grade III molecularly defined 1p19q co-deleted gliomas. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol 15:46–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctro.2018.12.003

Harary M, Kavouridis VK, Torre M et al (2020) Predictors and early survival outcomes of maximal resection in WHO grade II 1p/19q-codeleted oligodendrogliomas. Neuro Oncol 22(3):369–380. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/noz168

Kinslow CJ, Garton ALA, Rae AI et al (2019) Extent of resection and survival for oligodendroglioma: a US population-based study. J Neurooncol 144(3):591–601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-019-03261-5

Garnier L, Vidal C, Chinot O et al (2022) Characteristics of anaplastic oligodendrogliomas short-term survivors: a POLA network study. Oncologist 27(5):414–423. https://doi.org/10.1093/oncolo/oyac023

Halani SH, Yousefi S, Velazquez Vega J et al (2018) Multi-faceted computational assessment of risk and progression in oligodendroglioma implicates NOTCH and PI3K pathways. NPJ Precis Oncol 2:24. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-018-0067-9

Darvishi P, Batchala PP, Patrie JT et al (2020) Prognostic value of preoperative MRI metrics for diffuse lower-grade glioma molecular subtypes. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 41(5):815–821. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A6511

Jakola AS, Pedersen LK, Skjulsvik AJ, Myrmel K, Sjåvik K, Solheim O (2022) The impact of resection in IDH-mutant WHO grade 2 gliomas: a retrospective population-based parallel cohort study. J Neurosurg. https://doi.org/10.3171/2022.1.Jns212514

Alattar AA, Brandel MG, Hirshman BR et al (2017) Oligodendroglioma resection: a surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) analysis. J Neurosurg. https://doi.org/10.3171/2016.11.JNS161974

Jin K, Zhang SY, Li LW et al (2021) Prognosis of oligodendroglioma patients stratified by age: a SEER population-based analysis. Int J Gen Med 14:9523–9536. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijgm.S337227

Lawrie TA, Gillespie D, Dowswell T et al (2019) Long-term neurocognitive and other side effects of radiotherapy, with or without chemotherapy, for glioma. Cochrane Datab Syst Rev 8(8):CD013047. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013047.pub2

Kirkman MA, Hunn BHM, Thomas MSC, Tolmie AK (2022) Influences on cognitive outcomes in adult patients with gliomas: a systematic review. Front Oncol 12:943600. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.943600

Douw L, Klein M, Fagel SS et al (2009) Cognitive and radiological effects of radiotherapy in patients with low-grade glioma: long-term follow-up. Lancet Neurol 8(9):810–818. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(09)70204-2

Ahmad H, Martin D, Patel SH et al (2019) Oligodendroglioma confers higher risk of radiation necrosis. J Neurooncol 145(2):309–319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-019-03297-7

Acknowledgements

Figure 1 was created with BioRender.com. Thank you to Linus Köster for assistance with R statistical software.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Gothenburg. This study received financial support from the Swedish state under the agreement between the Swedish Government and the county councils [Avtal om Läkarutbildning och Forskning (ALF)], the ALF-agreement in the form of ALF-Grant (ALFGBG-965622) and from the Swedish Research Council (2017-00944). The sponsors had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed with acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. The statistical analysis and the first draft of the manuscript was made by LC. Study supervision was provided by AJ and AS. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no financial or non-financial interests to disclose that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical approval

The study involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the respective ethical committees of the regions involved: The Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics Central Norway approved the study but waived the need for informed consent (ref: 2014/1674). The Regional Ethical Committee in the Region of Västra Götaland approved the study but waived the need for informed consent (DNR 1067-16). The regional ethics committee, Regionala Etikprövningsnämnden Uppsala, approved the study protocol (Dnr 2015/210) but waived the need for informed consent for patients operated between 2005 and 2015. Inclusion of patients after January 2015 was based upon a written informed consent. The Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics in Stockholm approved the study protocol and waived the need for informed consent (Dnr: 2017/1760-31).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Carstam, L., Latini, F., Solheim, O. et al. Long-term follow up of patients with WHO grade 2 oligodendroglioma. J Neurooncol 164, 65–74 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-023-04368-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-023-04368-6