Abstract

Why do people express moral outrage? While this sentiment often stems from a perceived violation of some moral principle, we test the counter-intuitive possibility that moral outrage at third-party transgressions is sometimes a means of reducing guilt over one’s own moral failings and restoring a moral identity. We tested this guilt-driven account of outrage in five studies examining outrage at corporate labor exploitation and environmental destruction. Study 1 showed that personal guilt uniquely predicted moral outrage at corporate harm-doing and support for retributive punishment. Ingroup (vs. outgroup) wrongdoing elicited outrage at corporations through increased guilt, while the opportunity to express outrage reduced guilt (Study 2) and restored perceived personal morality (Study 3). Study 4 tested whether effects were due merely to downward social comparison and Study 5 showed that guilt-driven outrage was attenuated by an affirmation of moral identity in an unrelated context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Given an issue can be framed in either moral or non-moral terms (Van Bavel et al. 2012) a pilot study was conducted to ensure that the presentation of the issues in our studies (sweatshop labor in Studies 1, 4 and 5; environmentally destructive behavior in Studies 2 and 3), was perceived in moral terms. A separate sample of 151 MTurk participants indicated the extent to which their attitudes about sweatshop labor and people’s environmentally destructive behavior were “a reflection of your core moral beliefs and convictions” after reading the articles used in the primary studies. The item was adapted from previous research (Luttrell et al. 2016) and responses were made on a 7-point scale (1 = not at all, 7 = extremely). Supporting our assumption, one-sample t tests revealed that the means (M sweatshop = 5.66, M environment = 5.03) were significantly higher than the scales’ midpoint (4), t(150) = 14.35, p < .001 and t(150) = 8.14, p < .001, respectively.

To ensure sufficient power for the planned mediation analysis, we collected a large sample. In a simple mediation analysis (i.e., with a single mediator), and two small-to-moderate paths, a sample of 148 is necessary to achieve sufficient power (Fritz and McKinnon 2007). Given that the sequential mediation model incorporates two separate simple models, we collected approximately double this sample to ensure more than sufficient power for the planned analysis.

Pilot studies revealed that a small number of participants were unable to properly view the news articles due to technical issues (e.g., slow internet speeds, hardware issues). Based on this, all participants were asked if they had any difficulty viewing the news articles upon completion of the studies and excluded accordingly.

Although participants generally admitted to engaging in behaviors contributing to labor exploitation, self-reported contribution scores were not correlated with our primary variables of interest. This is consistent with the idea that felt guilt, rather than the mere recognition of one’s harm-doing, is the driving force behind subsequence increases in moral outrage and retributive action against perceived corporate harm-doing.

A sample size analysis using G*Power (Faul et al. 2007) revealed that in order to ensure .80 power for our primary analysis, assuming a small to medium effect size we would need a total sample size of 264. Factoring in the exclusion rate from Study 1 we estimated that we would need to collect approximately 307 participants.

A Responsibility × Order ANOVA on Perceived Victimization yielded no significant effects (responsibility: F(1, 263) = .04, p = .85; order: F(1, 263) = .07, p = .80; responsibility × order: F(1, 263) = .17, p = .68).

A sample size analysis using G*Power (Faul et al. 2007) revealed that in order to ensure .80 power for our primary analysis, assuming a small to medium effect size we would need a total sample size of 264. Factoring in the exclusion rate from the previous studies we estimated that we would need to collect approximately 307 participants.

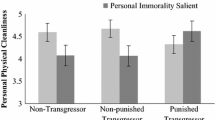

We conducted partial correlational analyses to assess the relationship between moral outrage at third-party harm-doing and perceived personal moral character within conditions. This analysis revealed a significant positive correlation between moral outrage scores and personal moral character ratings following a moral identity threat, r(60) = .25, p = .05. This correlation remained significant when belief in anthropogenic climate change scores were not included as a control, r(63) = .26, p = .04. There was no significant correlation between outrage and moral character in the absence of a moral identity threat, r(56) = .03, p = .85.

A sample size analysis using G*Power (Faul et al. 2007) revealed that in order to ensure .80 power for our primary analysis, assuming a small to medium effect size we would need a total sample size of 124. Factoring in the exclusion rate from the previous studies we estimated that we would need to collect approximately 148 participants.

As in Study 3 we conducted correlational analyses to test for the hypothesized relationship between moral outrage at third-party harm-doing and perceived personal moral character. Consistent with the previous study, this analysis revealed a significant positive correlation between moral outrage scores and personal moral character ratings following a moral identity threat, r(67) = .25, p = .05.

A sample size analysis using G*Power (Faul et al. 2009) revealed that in order to ensure .80 power for our primary analysis, assuming a small to medium effect size we would need a total sample size of 89. Factoring in the exclusion rate from the previous studies we estimated that we would need to collect approximately 100 participants.

References

Barkan, R., Ayal, S., Gino, F., & Ariely, D. (2012). The pot calling the kettle black: Distancing response to ethical dissonance. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 141, 757–773.

Batson, C. D. (2011). What’s wrong with morality? Emotion Review, 3, 230–236.

Batson, C. D., Thompson, E. R., Seuferling, G., Whitney, H., & Strongman, J. A. (1999). Moral hypocrisy: Appearing moral to oneself without being so. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 525–537.

Baumeister, R. F., Stillwell, A. M., & Heatherton, T. F. (1994). Guilt: An interpersonal approach. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 243–267.

Bellantoni, C., & Polantz, K. (2013, April 19). One year later: What happened to #stopkony? Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/newshour/rundown/one-year-later-what-happened-to-stopkony/

Branscombe, N. R., Doosje, B., & McGarty, C. (2002). Antecedents and consequences of collective guilt. In D. M. Mackie & E. R. Smith (Eds.), From prejudice to intergroup emotions: Differentiated reactions to social groups (pp. 49–66). New York: Psychology Press.

Branscombe, N. R., & Miron, A. M. (2004). Interpreting the ingroup’s negative actions toward another group: Emotional reactions to appraised harm. In L. Z. Tiedens & C. W. Leach (Eds.), The social life of emotions (pp. 314–335). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Branscombe, N. R., Slugoski, B., & Kappen, D. M. (2004). Collective guilt: what it is and what it is not. In N. R. Branscombe & B. Doosje (Eds.), Collective guilt: International perspectives (pp. 16–34). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Doosje, B., Branscombe, N. R., Spears, R., & Manstead, A. S. R. (1998). Guilty by association: When one’s group has a negative history. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 872–886.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 1149–1160.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191.

Fritz, M. S., & McKinnon, D. P. (2007). Required samples size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science, 18, 233–239.

Gausel, N., & Brown, R. (2012). Shame and guilt—Do they really differ in their focus of evaluation? Wanting to change the self and behavior in response to ingroup immorality. The Journal of Social Psychology, 152, 547–567.

Gausel, N., Leach, C. W., Vignoles, V. L., & Brown, R. (2012). Defend or repair? Explaining responses to in-group moral failure by disentangling feelings of shame, rejection, and inferiority. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102, 941.

Gausel, N., Vignoles, V. L., & Leach, C. W. (2016). Resolving the paradox of shame: Differentiating among specific appraisal-feeling combinations explains pro-social and self-defensive motivation. Motivation and Emotion, 40, 118–139.

Glick, P. (2005). Choice of scapegoats. In J. F. Dovidio, P. Glick, & L. A. Rudman (Eds.), On the nature of prejudice: Fifty years after Allport (pp. 244–261). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Gupta, P. (2012, January 27). Tim Cook responds to Foxconn worker abuse report: Apple not turning ‘blind eye’. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/01/27/tim-cook-foxconn_n_1237341.html

Haidt, J. (2003). The moral emotions. In R. J. Davidson, K. R. Scherer & H. H. Goldsmith (Eds.), Handbook of affective sciences (pp. 852–870). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Harth, N. S., Hornsey, M., & Barlow, F. K. (2011). Emotional responses to rejection of gestures of intergroup reconciliation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37, 815–829.

Harth, N., Leach, S. C. W., & Kessler, T. (2013). Guilt, anger, and pride about ingroup environmental behavior: Different emotions predict distinct intentions. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 34, 18–26.

Harvey, R. D., & Oswald, D. L. (2000). Collective guilt and shame as motivation for white support of black programs. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30, 1790–1811.

Hathaway, J. (2014, October 10). What Is Gamergate, and Why? An Explainer for Non-Geeks. Retrieved from http://gawker.com/what-is-gamergate-and-why-an-explainer-for-non-geeks-1642909080

Hoffman, M. L. (2000). Empathy and moral development: Implications for caring and justice. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Iyer, A., Leach, C. W., & Crosby, F. J. (2003). White guilt and racial compensation: The benefits and limits of self-focus. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 117–129.

Iyer, A., Schmader, T., & Lickel, B. (2007). Why individuals protest the perceived transgressions of their country: The role of anger, shame, and guilt. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 572–587.

Jordan, J., Hoffman, M., Bloom, P., & Rand, D. G. (2016). Third-party punishment as costly signal of trustworthiness. Nature, 530, 473–476.

Jordan, J., Mullen, E., & Murnighan, J. K. (2011). Striving for the moral self: The effects of recalling past moral actions on future moral behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37, 701–713.

Keltner, D., Haidt, J., & Shiota, M. N. (2006). Social functionalism and the evolution of emotions. In M. Schaller, J. A. Simpson & D. T. Kendrick (Eds.), Evolution and Social Psychology (pp. 115–142). New York: Psychology Press.

Leach, C. W., Ellemers, N., & Barreto, M. (2007). Group virtue: The importance of morality (vs. competence and sociability) in the positive evaluation of ingroups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 234–249.

Leach, C. W., Snider, N., & Iyer, A. (2002). Poisoning the consciences of the fortunate: The experience of relative advantage and support for social equality. In I. Walker & H. J. Smith (Eds.), Relative deprivation (pp. 136–163). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lodewijkz, H. F. M., Kersten, G. L. E., & van Zomeren, M. (2008). Dual pathways to engage in “silent marches” against violence: Moral outrage, moral cleansing and modes of identification. Journal of Community and Applied Psychology, 18, 153–167.

Luttrell, A., Petty, R. E., Briñol, P., & Wagner, B. C. (2016). Making it moral: Merely labeling an attitude as moral increases its strength. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 65, 82–93.

Mazar, N., Amir, O., & Ariely, D. (2008). The dishonesty of honest people: A theory of self-concept maintenance. Journal of Marketing Research, 45, 633–644.

McGarty, C., Pedersen, A., Leach, C. W., Mansell, T., Waller, J., & Bliuc, A. (2005). Group-based guilt as a predictor of commitment to apology. British Journal of Social Psychology, 44, 659–680.

Merritt, A. C., Effron, D., & Monin, B. (2010). Moral licensing: When being good frees us to be bad. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4, 344–357.

Miron, A. M., Branscombe, N. R., & Biernat, M. R. (2010). Motivated shifting of justice standards. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36, 768–779.

Monin, B., & Jordan, A. H. (2009). Dynamic moral identity: A social psychological perspective. In D. Narvaez & D. Lapsley (Eds.), Personality, identity, and character: Explorations in moral psychology (pp. 341–354). Cambridge: University Press.

Montada, L., & Schneider, M. (1989). Justice and emotional reactions to the disadvantaged. Social Justice Research, 3, 313–344.

Nisan, M. (1991). The moral balance model: Theory and research extending our understanding of choice and deviation. In W. M. Kurtines & J. L. Gerwitz (Eds.), Handbook of moral behavior and development (Vol. 3, pp. 213–249). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

O’Connor, L. E. (2010). Guilt. In I. B. Weiner & W. E. Craighead (Eds.), Corsini encyclopedia of psychology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley

Pagano, S., & Huo, Y. J. (2007). The role of moral emotions in predicting support for political actions in post-war Iraq. Political Psychology, 28, 227–255.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891.

PEW, (2014, June 12). Political polarization in the American republic. Retrieved from http://www.people-press.org/2014/06/12/political-polarization-in-the-american-public/

Rothschild, Z. K., Landau, M. J., Keefer, L. A., & Sullivan, D. (2015). Another’s punishment cleanses the self: Evidence for a moral cleansing function of punishing transgressors. Motivation and Emotion. doi:10.1007/s11031-015-9487-9. (Advanced online publication)

Rothschild, Z. K., Landau, M. J., Molina, L. E., Branscombe, N. R., & Sullivan, D. (2013). Displacing blame over the ingroup’s harming of a disadvantaged group can fuel moral outrage at a third-party scapegoat. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49, 898–906.

Rothschild, Z. K., Landau, M. J., Sullivan, D., & Keefer, L. A. (2012). A dual-motive model of scapegoating: Displacing blame to reduce guilt or increase control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102, 1148–1163.

Sandberg, T., & Conner, M. (2008). Anticipated regret as an additional predictor in the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. British Journal of Social Psychology, 47, 589–606.

Stewart, T. L., Latu, I. M., Branscombe, N. R., & Denney, H. T. (2010). Yes we can! Prejudice reduction through seeing (inequality) and believing (in social change). Psychological Science, 21, 1557–1562.**

Tangney, J. P. (1992). Self-conscious emotions: The self as a moral guide. In T. Abraham, D. A. Staple & J. V. Wood (Eds.), Self and motivation: Emerging psychological perspectives (pp. 97–117). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Tangney, J. P. (1995). Recent advances in the empirical study of shame and guilt. The American Behavioral Scientist, 38, 1132–1145.

Tangney, J. P., Stuewig, J., & Mashek, D. J. (2007). Moral emotions and moral behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 345–372.

Tarrent, M., Branscombe, N. R., Warner, R., & Weston, D. (2012). Social identity and perceptions of torture: It’s moral when we do it! Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48, 513–518.

Täuber, S., & van Zomeren, M. (2013). Outrage towards whom? Threats to moral group status impede striving to improve via out-group-directed outrage. European Journal of Social Psychology, 43, 149–159.

Thomas, A. J., Stanford, P. K. & Sarnecka, B.W. (2016). No child left alone: Moral judgments about parents affect estimates of risk to children. Collabra, 2(1), 10. DOI: 10.1525/collabra.33.

Thomas, E. F. (2005). The role of social identity in creating positive beliefs and emotions to motivate volunteerism. Australian Journal on Volunteering, 10, 45–52.

Thomas, E. F., McGarty, C., & Mavor, K. I. (2009). Transforming “Apathy into movement”: The role of prosocial emotions in motivating action for social change. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 13, 310–333.

Thompson, M. M., Naccarato, M. E., Parker, K. C. H., & Moskowitz, G. (2001). The Personal Need for Structure (PNS) and Personal Fear of Invalidity (PFI) scales: Historical perspectives, present applications and future directions. In G. Moskowitz (Ed.), Cognitive social psychology: The Princeton symposium on the legacy and future of social cognition (pp. 19–39). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Van Bavel, J. J., Packer, D. J., Haas, I. J., & Cunningham, W. A. (2012). The importance of moral construal: Moral versus non-moral construal elicits faster, more extreme, universal evaluations of the same actions. PLoS ONE, 7(11), e48693.

Vidmar, N. (2000). Retribution and revenge. In J. Sanders & V. L. Hamilton (Eds.), Handbook of justice research in law (pp. 31–63). New York: Kluwer.

Wang, X., & McClung, S. R. (2012). The immorality of illegal downloading: The role of anticipated guilt and general emotions. Computers and Human Behavior, 28, 153–159.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070.

Wills, T. A. (1981). Downward comparison principles in social psychology. Psychological Bulletin, 90, 245–271.

Funding

These studies were funded by the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Zachary Rothschild declares that he has no conflict of interest. Lucas Keefer declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rothschild, Z.K., Keefer, L.A. A cleansing fire: Moral outrage alleviates guilt and buffers threats to one’s moral identity. Motiv Emot 41, 209–229 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-017-9601-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-017-9601-2