Abstract

Elemental isotopic ratios are measured in various research fields and provide useful information regarding age, origin, geological and biological activities, ancient climate, etc. Here, we report a new isotopic analysis method without sample destruction using muon-induced characteristic X-rays. We demonstrated this method by conducting muon-beam irradiation experiments on two Pb plates with different isotopic ratios: natural isotopic composition and artificially enriched 208Pb. The observed broad X-ray peaks of the Pb Kα line around 6 MeV were deconvolved with 206Pb, 207Pb, and 208Pb isotopes, giving the isotopic ratios. The resulting isotopic ratios were consistent with those obtained from mass spectrometry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The isotopic composition as well as chemical composition of a material provides important information on various natural phenomena and human activities through the associated isotopic effects of chemical and physical reactions (e.g. evaporation, condensation, diffusion, isotopic exchange, radiometric decay, etc.). Specifically, isotopes of Pb are of particular importance in archaeology, Earth and planetary science, and other scientific fields because they provide insights into the origin of the material [1, 2]. For example, the isotopic ratio of Pb can identify the production area of archaeological artefacts (e.g. bronze products) because the ratio depends on the origin of the ore [3, 4]. This is owing to the inhomogeneous distribution of uranium and thorium deposited by Earth’s formation, which continually produce lead by radioactive decay. In the field of Earth and planetary science, on the other hand, the isotopic ratio of Pb has been used to determine the crystallization and/or alteration age of minerals [5, 6].

Various methods of determining the isotopic ratios of various samples exist. The majority of these methods are based on mass spectrometry owing to its high level of accuracy. The application of mass spectrometry, however, necessarily results in sample destruction. Thus, a non-destructive method of determining the isotopic ratio is highly desirable, especially for the analysis of precious samples.

In this paper, we report a new method of isotopic determination by measuring muon-induced characteristic X-rays. Muons are elementary particles with charge equal to that of an electron and mass 207 times that of an electron. Recent advances in accelerator technology have led to the emergence of intense muon beams [7, 8], thus making non-destructive elemental analysis by muonic X-ray measurement practical [9].

When a muon is introduced to a substance, the muon is captured in the Coulomb field of the nucleus and forms a muonic atom. The orbit of the captured muon is very different from the electron’s orbit. The muon exists in highly excited atomic muon level just after muon capture in the atom and immediately de-excites to muonic 1 s level with emitting muonic X-rays [10,11,12]. The muon atomic orbit is very close to the nucleus and has a large binding energy owing to its large mass. Therefore, muonic X-rays have very high energies, and as a result, those generated in the interior of a substance can easily escape from the sample. The selected incident energy of the accelerated muon determines the stopping depth in the substance whereby three-dimensional muonic X-ray analysis of the resulting light elements is possible [13, 14]. Non-destructive elemental analysis using this method has already been demonstrated for serval valuable samples (e.g., Ninomiya et al. and Hampshire et al. used this method to determine the internal elemental distribution in archaeological artefacts [14,15,16,17], and Terada et al. succeeded in quantifying carbon contents in carbonaceous meteorites [13, 18, 19]).

It is important to note that the muon atomic orbit is 207 times closer to the nucleus than the electron orbit owing to its increased mass (i.e. 207 times that of an electron). Therefore, the muon orbit of the inner shell (e.g. the 1 s orbit) is strongly affected by properties of the nucleus, especially the distribution of protons in the nucleus [20]. Because the atomic muon level is affected by the mass of the nuclide, the energy of the muonic characteristic X-rays depends on the mass of the nuclide (i.e., so-called “isotope shift”). For example, Kessler et al. reported the energies of muonic Kα1 X-rays of lead atoms as 5778 keV for 208Pb, 5784 keV for 207Pb, 5787 keV for 206Pb and 5796 keV for 204Pb [21]. These represent isotope shifts of serval keV. Previous studies have measured the isotopic shift of muonic X-rays to investigate the distribution of protons in the nucleus [20]. In this study, we aimed to leverage the isotope shift to develop non-destructive isotopic analysis methods for Pb, an important element in archaeology and geochemistry.

Experimental

Non-destructive isotopic analysis by muon-beam irradiation

Muon irradiation experiments were carried out in the Japan Proton Accelerator Complex (J-PARC). The muon facility (MUSE; MUon Science Establishment) of J-PARC contains the highest intensity pulsed muon beam in the world [7]. To produce the muon beam, 3 GeV protons of 150-kW (primary proton beam intensity of 50 μA) with a 25-Hz pulse structure bombarded a graphite target. The generated muons were transported to the D2 beam line where an aluminium vacuum chamber was connected directly to the end of the beam line. We used two 3-g Pb samples, 22 mm in diameter and 0.7 mm thick, one having natural isotopic abundance (The Nilaco Corporation determined isotopic abundance as 208Pb: 51.5%, 207Pb: 22.3%, 206Pb: 24.7% and 204Pb: 1.4% by mass spectrometry) and the other enriched 208Pb (Pb ingot from ISOFLEX USA, 208Pb: 99.57%, 207Pb: 0.35%, 206Pb: 0.01%, and 204Pb: 0.07%). Each sample was set in the centre of the chamber for its muon irradiation.

Four high-purity germanium detectors were placed around the chamber to measure the muonic X-rays emitted following muon capture in the sample. Three types of detectors were used in these measurements: one GL0110 (CANBERRA Ind.) detector for low-energy muonic X-ray measurement (i.e. 0–200 keV), one GLP36360 (ORTEC Ind.) detector for the medium-energy region (i.e. 0–800 keV), and two GMX20P4 (ORTEC Ind.) detectors for high-energy muonic X-ray measurement (i.e. 0–8000 keV). These detectors were placed at a distance of 170–1150 mm from the sample. The data from the three GMX detectors were used in the muonic Kα X-ray analysis. Further details of the experimental setup are given elsewhere [22].

We used this setup to conduct two experiments (2016B0207 and 2017A0177). In the 2016B0207 experiment, natPb and 208Pb samples were irradiated for 40 and 14 h, respectively. In the 2017A0177 experiment, the irradiation times for natPb and 208Pb samples were 22 and 16 h, respectively. In both experiments, we selected the incident muon momentum as 30 MeV/c, which corresponds to a kinetic energy of 4.2 MeV. Under these conditions, the muon beam stops at a depth of 0.2 mm in the lead sample. The intensity of the muon beam depends on the muon momentum. Based on the muonic X-ray intensity, we estimated the number of stopped muons in the sample to be about 3000 /s at an incident muon momentum of 30 MeV/c.

Determination of isotopic ratio by mass spectrometry

The isotopic abundance of the natPb sample was analysed by the multi-turn TOF–SIMS (Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry) system (OPTIMA: Osaka PosT-Ionization MAss spectrometer) at Osaka University. The sample was sputtered by a Ga ion beam of a FIB system, and the sputtered atoms were then ionized by a femto-second laser system. These ions were guided to the multi-turn time-of-flight mass spectrometer (MULTUM) and detected by a multi-channel plate for separation of m/z. The 204, 206, 207, and 208 mass-number counting rates determined the isotopic ratios of 208Pb/204Pb, 207Pb/204Pb, and 206Pb/204Pb. We repeated these measurements ten times to obtain the isotopic ratios of 36.26 ± 0.60 for 208Pb/204Pb, 15.72 ± 0.27 for 207Pb/204Pb, and 17.40 ± 0.29 for 206Pb/204Pb. Further details of the mass spectrometry measurement methods are given elsewhere [23].

Results and discussion

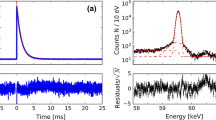

Figure 1 shows the muonic X-ray spectra obtained from the muon irradiation experiments for natPb and enriched 208Pb samples. Figure 1a shows spectrum for GMX detector in 2016B0207 experiment and Fig. 1b shows that for GLP detector. Muonic X-rays were observed in the energy range up to 6 MeV because the muon is 207 times more massive than the electron, as previously mentioned. In the initial stage of muonic atom formation, the muon is captured in a highly excited muonic orbit. There is only one muon in the muonic atom and all inner muon atomic orbits are vacant. As a result, one captured muon emits many muonic X-rays, such as Kα, Lα, Mα, Nα, etc., by a muon cascade process. Some gamma-rays emitted after muon absorption by the nucleus were also observed [22].

a Muonic X-ray spectrum obtained by muon irradiation of the natPb sample for GMX detector 2016B0207 experiment and b muonic X-ray spectrum obtained by muon irradiation of the natPb sample for GLP detector. Cascading muonic X-rays such as K, L, M, and N lines were clearly observed. c Enlarged view of the muonic Kα X-ray region. Owing to the large energy gap between muonic 2p1/2 and 2p3/2 states, Kα1 and Kα2 X-rays appeared into two different energy regions. Each peak appeared as a single sharp component in the 208Pb sample. The broadening observed in the natPb sample was due to the presence of the isotopic shift

Figure 1c shows an enlarged view of the muonic X-ray spectra for the Kα X-ray region (5600–6200 keV) for one of GMX detector in 2016B0207 experiment. For the enriched 208Pb sample, one sharp peak was observed in each of the Kα1(2p1/2-1s1/2) and Kα2(2p3/2-1s1/2) X-ray regions. In the natPb sample, on the other hand, the Kα1 and Kα2 X-ray peaks exhibited a broad peak and a tail component on the high-energy side. The low-energy region of each broadened peak was consistent with the peak position obtained from the 208Pb sample. The spread of each peak in the high-energy region was consistent with the expected energy of the muonic X-rays of 207Pb and 206Pb [21].

In order to investigate the contribution from each isotope, we deconvolved a fit of the broadened peaks in the muonic X-ray spectrum. First, we fit the single peaks of the Kα1 and Kα2 X-rays from the 208Pb sample with one Gaussian function and determined the peak centre and width. Using these as fixed parameters, along with peak centres of 206Pb and 207Pb taken from the literature, we fitted the broad Kα X-ray peaks obtained from the natPb one of example is shown in Fig. 2 [21]. It should be noted that the 204Pb peak was not taken into consideration because of its negligibly low intensity.

Expanded muonic Pb Kα1 X-ray spectrum together with fitting components from each isotope and background. The full width half-maximum of each fitted peak was determined from the fit of the 208Pb sample and the peak centres were obtained from the literature [21] (see text)

This fitting procedure resulted in the identification of the intensities of the muonic X-rays from 206Pb, 207Pb, and 208Pb. Figure 3 shows the isotopic ratios determined from the Kα1 and Kα2 X rays of 208Pb/206Pb and 207Pb/206Pb for each experiment and detector, and the weighted mean values. The resulting isotopic ratios were consistent despite the differences between the two experiments and two detectors. The weighted mean isotopic ratios were 1.85 ± 0.15 for 208Pb/206Pb and 0.77 ± 0.10 for 207Pb/206Pb. The magnitudes of the isotopic ratios were determined by the intensities of 206Pb, 207Pb, and 208Pb X-rays divided by the sum of their X-ray intensities (i.e. 51.0% for 208Pb, 21.3% for 207Pb, and 27.6% for 206Pb). The isotopic ratios determined by these methods are in good agreement with those determined by mass spectrometry, i.e., 2.08 ± 0.06 for 208Pb/206Pb and 0.90 ± 0.03 for 207Pb/206Pb.

Isotopic ratios determined from the intensity ratios of muonic Kα X-rays for (a) 208Pb/206Pb and (b) 207Pb/206Pb. The values obtained from each of the two detectors (detector 1, and 2) in the two individual muon irradiation experiments (2016B0207 and 2017A0177) are consistent with each other. The weighted mean values from four data are also shown. The dashed line and shaded region show the corresponding value obtained from mass spectrometry and its errors, respectively

Conclusions

We succeeded in non-destructive isotopic analysis by muonic X-ray measurement for the first time. Isotope shifts of muonic X-rays exist in any elements, so this method can be applied to any element in various samples. The accuracy achieved by this method, however, is currently insufficient for conducting contemporary research such as identifying the production area of archaeological artefacts and dating geochemical samples. The J-PARC muon facility has begun testing a 1-MW primary proton beam, which is more than six times the beam intensity used in this experiment, and the accuracy can be improved by using the intense muon beam in addition to optimizing the experimental setup.

References

Longman J, Veres D, Ersek V, Phillips DL, Chauvel C, Tamas CG (2018) Quantitative assessment of Pb sources in isotopic mixtures using a Bayesian mixing model. Sci Rep 8:6154. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-24474-0

Mathuthu M, Khumalo N (2018) Determination of lead isotope ratios in uranium mine products in South Africa by means of inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 315:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-017-5641-z

Goucher CL, Teilhet JH, Wilson KR, Chow TJ (1976) Lead isotope studies of metal source for ancient Nigerian ‘bronzes’. Nature 262:130–131. https://doi.org/10.1038/262130a0

Brill RH, Yamakaki K, Barnes IL, Rosman KJR, Diaz M (1979) Lead isotopes in some Japanese and Chinese glasses. Airs Orientals 11:87–109

Patterson C (1956) Age of meteorites and the earth. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 10:230–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(56)90036-9

Amelin Y, Krot AN, Hutcheon ID, Ulyanov AA (2002) Lead isotopic ages of chondrules and calcium–aluminum–rich inclusions. Science 297:1678. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1073950

Shimomura K, Koda A, Strasser P, Kawamura N, Fujimori H, Makimura S, Nakahara K, Ishida K, Nishiyama K, Miyake Y (2009) Superconducting muon channel at J-PARC. Nucl Instr Methods A 600:192–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2008.11.029

Cook S, D’Arcy R, Edmonds A, Fukuda M, Hatanaka K, Hino Y, Kuno Y, Lancaster M, Mori Y, Ogitsu T, Sakamoto H, Sato A, Tran NH, Truong NM, Wing M, Yamamoto A, Yoshida M (2017) Delivering the world’s most intense muon beam. Phys Rev Accel Beams 20:030101. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevAccelBeams.20.030101

Kubo K (2016) Non-destructive elemental analysis using negative muon. J Phys Soc Jpn 85:091015. https://doi.org/10.7566/JPSJ.85.091015

Ponomarev LI (1973) Ann Rev Nucl Sci 23:395. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ns.23.120173.002143

Measday DF (2001) The nuclear physics of muon capture. Phys Rep 354:243–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0370-1573(01)00012-6

Yoshida G, Ninomiya K, Higemoto W, Ito TU, Nagatomo T, Strasser P, Kawamura N, Shimomura K, Miyake Y, Miura T, Kubo MK, Shinohara A (2015) Muon capture probability of carbon and oxygen for CO, CO2, and COS under low-pressure gas conditions. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 303:1277–1281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-014-3602-3

Terada K, Ninomiya K, Osawa T, Tachibana S, Miyake Y, Kubo MK, Kawamura N, Higemoto W, Tsuchiyama A, Ebihara M, Uesugi M (2014) A new X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy for extraterrestrial materials using a muon beam. Sci Rep 4:5072. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05072

Ninomiya K, Kubo MK, Nagatomo T, Higemoto W, Ito TU, Kawamura N, Strasser P, Shimomura K, Miyake Y, Suzuki T, Kobayashi Y, Sakamoto S, Shinohara A, Saito T (2015) Nondestructive elemental depth-profiling analysis by muonic X-ray measurement. Anal Chem 87:4597–4600. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.5b01169

Ninomiya K, Nagatomo T, Kubo K, Ito TU, Higemoto W, Kita M, Shinohara A, Strasser P, Kawamura N, Shimomura K, Miyake Y, Saito T (2012) Development of non destructive and quantitative elemental analysis method using calibration curve between muonic X-ray intensity and elemental composition in bronze. Bull Chem Soc Jpn 85:228–230. https://doi.org/10.1246/bcsj.20110151

Ninomiya K, Inagaki M, Kubo MK, Nagatomo T, Higemoto W, Kawamura N, Strasser P, Shimomura K, Miyake Y, Sakamoto S, Shinohara A, Saito T (2016) Negative muon induced elemental analysis by muonic X-ray and prompt gamma-ray measurements. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 309:65–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-016-4772-y

Hampshire B, Butcher K, Ishida K, Green G, Paul D, Hillier A (2019) Using negative muons as a probe for depth profiling silver roman coinage. Heritage 2:400–407. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2010028

Terada K, Sato A, Ninomiya K, Kawashima Y, Shimomura K, Yoshida G, Kawai Y, Osawa T, Tachibana S (2017) Non-destructive elemental analysis of a carbonaceous chondrite with direct current Muon beam at MuSIC. Sci Rep 7:15478. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15719-5

Osawa T, Ninomiya K, Yoshida G, Inagaki M, Kubo MK, Kawamura N, Miyake Y (2015) Elemental analysis system with negative-muon beam. JPS Conf Proc 8:025003. https://doi.org/10.7566/JPSCP.8.025003

Fricke G, Bernhardt C, Heilig K, Schaller LA, Schellenberg L, Shera EB, De Jager CW (1995) Nuclear ground state charge radii from electromagnetic interactions. Atom Data Nucl Data 60:177–285. https://doi.org/10.1006/adnd.1995.1007

Kessler D, Mes H, Thompson AC, Anderson HL, Dixit MS, Hargrove CK, McKee RJ (1975) Muonic X rays in lead isotopes. Phys Rev C 11:1719–1734. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.11.1719

Ninomiya K, Kubo MK, Strasser P, Shinohara A, Tampo M, Kawamura N, Miyake Y (2018) Isotope identification of lead by muon induced X-ray and gamma-ray measurements. JPS Conf Proc 21:011043. https://doi.org/10.7566/JPSCP.21.011043

Terada K, Kawai Y, Toyoda M, Ishihara M, Aoki J, Yabuta H, Miya K, Suwa T, Matsuda T, Nakamura R (2017) Development on Multi-Turn TOF-SIMS with a femto-second laser for post ionization: first application of OPTIMA (Osaka PosT-Ionization MAss spectrometer) for presolar SiCs. JPS Conf Proc 14:011103. https://doi.org/10.7566/JPSCP.14.011103

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr. K. Hamada and Mr. S. Doiuchi (WDB EUREKA) for their kind support in the muonic X-ray measurements. The muon experiment at the Materials and Life Science Experimental facility of J-PARC was performed under a user program (Proposal No. 2016B0207 and 2017A0177). This research was partially supported by the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (JP18H05457, B01 team of “Toward new frontiers: Encounter and synergy of state-of-the-art astronomical detectors and exotic quantum beams”) and the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (JP18K11922).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ninomiya, K., Kudo, T., Strasser, P. et al. Development of non-destructive isotopic analysis methods using muon beams and their application to the analysis of lead. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 320, 801–805 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-019-06506-9

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-019-06506-9