Abstract

Native speakers of English regularly hear sentences without overt subjects. Nevertheless, they maintain a [\(-\)pro] grammar that requires sentences to have an overt subject. It is proposed that listeners of English recognize that speakers reduce predictable material and thus attribute null subjects to this process, rather than changing their grammars to a [\(+\)pro] setting. Mack et al. (J Memory Lang 67(1):211–223, 2012) showed that sentences with noise covering the subject are analyzed as having null subjects more often with a first person pronoun and with a present tense—properties correlated with more predictable referents—compared to a third person pronoun and past tense. However, those results might in principle have been due to reporting null subjects for verbs that often occur with null subjects. An experiment is reported here in which comparable results are found for sentences containing nonsense verbs. Participants preferred a null subject more often for first person present tense sentences than for third person past tense sentences. The results are as expected if participants are responding to predictability, the likelihood of reduction, rather than to lexical statistics. The results are argued to be important in removing a class of mis-triggering examples from the language acquisition problem.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

There are many reasons to assume that linguistic knowledge includes an abstract system of rules, constraints or principles. One reason is to account for the human ability to produce and understand novel utterances, including highly implausible ones, involving very low frequency structures. Other reasons include generalizations such as the relation between the existence of expletive subjects in a language and the requirement of an overt subject. Such generalizations are expected if linguistic knowledge is treated as a system but not otherwise since the generalization is not a surface generalization nor is it logically entailed. But of course this issue goes far beyond what can be discussed in a brief article. So for present purposes we simply make the assumption of the mental existence of a grammar.

In a pilot study, 10 people rated 12 isolated null subject sentences from Mack et al. in a written questionnaire, using a 5-point scale. As expected, the present tense examples were rated higher (3.47) than the past tense examples (2.77).

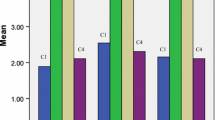

A logistic mixed model was fit, using random intercepts and slopes of subjects and items. The fixed effect of tense/person was highly significant (b \(=\) 1.26, SE \(=\) 0.4015, t \(=\) 3.147, p \(=\) 0.00165).

References

Albright, A., & Hayes, B. (2003). Rules vs. analogy in English past tenses: A computational/experimental study. Cognition, 90, 119–161.

Brown, P. M., & Dell, G. S. (1987). Adapting production to comprehension: The explicit mention of instruments? Cognitive Psychology, 19(4), 441–472.

Fowler, C. A., & Housum, J. (1987). Talkers’ signaling of new and old words in speech and listeners’ perception and use of the distinction. Journal of Memory and Language, 26, 489–504.

Frazier, L. (2012). Two interpretive systems for natural language? In Fernandez, E., Fodor, J., (Eds.), Grammars and parsers: Papers from the special session of the CUNY conference on human sentence processing. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research.

Frazier, L. (2014). Going beyond one’s current grammar. In Proceedings of Boston University language development conference. Cascadilla Press.

Frazier, L., & Clifton, C. (2011). Quantifiers undone: Reversing predictable speech errors in comprehension. Language, 87(1), 158–171.

Hyams, N. (2012). Missing subjects in early child language. In Jill De Villiers & Thomas Roeper (Eds.), Handbook of Generative Approaches to Language Acquisition. Berlin: Springer.

Jaeger, T. F. (2010). Redundancy and reduction: Speakers manage syntactic information density. Cognitive Psychology, 61(1), 23–62.

Mack, J., Clifton, C, Jr, Frazier, L., & Taylor, P. V. (2012). Pragmatic constraints influence the restoration of optional subjects. Journal of Memory and Language, 67(1), 211–223.

Omaki, A., & Lidz, J. (2014). Linking parser development to acquisition of syntactic knowledge. Language Acquisition.

Rohdenburg, G. (1996). Cognitive complexity and increased grammatical explicitness in English. Cognitive Linguistics, 7, 149–182.

Snedeker, J. (2009). Sentence processing. In Edith L. Bavin (Ed.), The Cambridge Handbook of Child Language (pp. 321–337). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Valian, V., Hoeffner, J., & Aubry, S. (1996). Young children’s imitations of sentence subjects: Evidence of processing limitations. Developmental Psychology, 32(1), 153–164.

Weir, A. (2012). Left edge deletion in English and subject omission in diaries. English Language and Linguistics, 16(1), 105–29.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Grant HD18708 to the University of Massachusetts. I am grateful to Amanda Rysling for discussion and for bringing the relevance of Albright and Hayes (2003) to my attention, and to Chuck Clifton for help with all aspects of this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Both forms are illustrated for item #1; only the present tense form is illustrated for the other items.

-

1.

-

a.

How does that trif to you?

-

Which answer sounds more natural?

-

Trifs good to me., It trifs good to me.

-

-

b.

How did that trif to him?,

-

Which answer sounds more natural?

-

Triffed good to him., It triffed good to him.

-

-

a.

-

2.

Glits like fun to me., It glits like fun to me.

-

3.

Snells very cold to me., It snells very cold to me.

-

4.

Shees humid to me., It shees humid to me.

-

5.

Skells like a bad idea to me., It skells like a bad idea to me.

-

6.

Murns a bit crazy to me., It murns a bit crazy to me.

-

7.

Spacks perfect to me., It spacks perfect to me.

-

8.

Stips like heavy rain to me., It stips like heavy rain to me.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Frazier, L. Do Null Subjects (mis-)Trigger Pro-drop Grammars?. J Psycholinguist Res 44, 669–674 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-014-9312-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-014-9312-8