Abstract

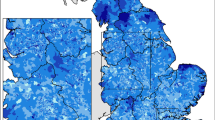

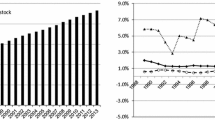

This study deals with counterurbanisation in Sweden and how it can be understood and explained by a focus on both demography and housing market conditions at a low geographical level. A central concept is the hotspot. A hotspot is a place that appears side by side with other places considered to be degenerated or deprived, but where a certain process has taken place—a process which over time transforms the place into an attractive destination. The objective of the study is twofold. The first object focuses on whether hotspots have grown in Northern Sweden. The second objective draws attention to place characteristics and change, and whether demographic and socioeconomic features contribute to explaining the occurrence of hotspots. The data are derived from a longitudinal register-based database maintained by Statistic Sweden. The database allows a detailed analysis of the growth of hotspots, here identified through a Tobin’s q model of changes in house prices from 2000 to 2008 at the neighbourhood level. Next, the transformation into hotpots is tested by a logistic regression analysis where changes in demography and socioeconomic composition and Tobin’s q are analysed simultaneously. The results indicate that hotspots have emerged in Northern Sweden. An influx of a more affluent population contributes to a socioeconomic and demographic transformation of places into hotspots. However, hotspots do not grow in the most rural countryside, but in the countryside close to urban areas with commuting opportunities. This implies that both urban proximity and rural amenities are positively valued.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The total number of municipalities in Sweden is 290 and in the Northern Sweden 54. A municipality in a Swedish context is a territorially defined area, an administrative unit of local government, a political organization with directly elected policymakers, legal entity with mandatory membership, which may enter into contracts and own real and personal property (www.ne.se). The municipalities are here divided into categories based on structural parameters such as population, population density, commuting pattern and economic structure. This functional classification of municipalities is made by the Swedish Association of Local Authorities.

References

Amcoff, J., & Westholm, E. (2007). Understanding rural change—demography as key to the future. Futures, 39(4), 363–379.

Andersson, E. (2012). Understanding hotspots in Northern Sweden—the housing market and households in the Swedish countryside. Department of human geography, Stockholm University. Memo.

Berg, L., & Berger, T. (2006). The Q theory and the Swedish housing market—an empirical test. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economic, 33(4), 329–344.

Berry, B. J. L. (1978). The counterurbanization process: How general? In N. M. Hansen (Ed.), Human settlement system (pp. 25–49). Cambridge: Ballinger Publishing Company.

Champion, A. G. (1994). Population change and migration in Britain since 1981: Evidence for continuing deconcentration. Environment and Planning A, 26(10), 1501–1520.

Champion, A. G. (2001). A changing demographic regime and evolving polycentric urban regions: Consequences for the size, composition and distribution of city populations. Urban Studies, 38(4), 657–677.

Dahms, F. A. (1995). ‘Dying villages’, ‘counterurbanization’ and the urban field—a Canadian perspective. Journal of Rural Studies, 11(1), 21–33.

Database Geosweden (2011).

Elliot, J. R. (1997). Cycles within the system: Metropolitanisation and internal migration in US, 1965–90. Urban Studies, 34(1), 21–41.

Eurostat (2010). epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/statistics/themes.

Glaeser, E. L., & Gyourko, J. (2005). Urban decline and durable housing. Journal of Political Economy, 113(2), 345–375.

Hedin, K., Clark, E., Lundholm, E., & Malmberg, G. (2012). Neoliberalization of housing in Sweden: Gentrification, filtering, and social polarization. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 102(2), 443–463.

Hines, J. D. (2010). Rural gentrification as permanent tourism: The creation of the ‘New’ west archipelago as postindustrial cultural space. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 28(3), 509–525.

Johannisson, B., Persson, L. O., & Wiberg, U. (1989). Urbaniserad glesbygd—verklighet och vision. Arbetsmarknadsdepartementet, Ds 1989:22.

Kontuly, T. (1998). Contrasting the counterurbanisation experience in European Nations. In P. Boyle & K. Halfacree (Eds.) Migration into rural areas. Theories and issues. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Lepczyk, C. A., Hammer, R. B., Stewart, S. I., & Radeloff, V. C. (2007). Spatiotemporal dynamics of housing growth hotspots in the North Central U.S. from 1940 to 2000. Landscape Ecology, 22, 939–952.

Magnusson, L. (2005). Gentrification—the prospect for European cities? Open House International, 30(3), 54–60.

Magnusson, L., & Turner, B. (2003). Countryside abandoned?—suburbanisation and mobility in Sweden. European Journal of Housing Policy, 3(1), 35–60.

Magnusson, L., & Turner, B. (2006). På spaning efter “hotspots” i norra Sverige—en förstudie. Uppsala universitet, Institutet för bostads- och urbanforskning. Memo.

Meen, D., & Meen, G. (2003). Social behaviour as a basis for modelling the urban housing market: A review. Urban Studies, 40(5–6), 917–935.

Millard Ball, A. (2002). Gentrification in a residential mobility framework: Social change, tenure change and chains of moves in stockholm. Housing Studies, 17(6), 833–856.

Ord, J. K., & Getis, A. (2001). Testing for local spatial autocorrelation in the presence of global autocorrelation. Journal of Regional Science, 41(3), 411–432.

Phillips, M. (1993). Rural gentrification and the processes of class colonisation. Journal of Rural Studies, 9(2), 123–140.

Phillips, M. (2009). Gentrification, rural. In International encyclopedia of human geography (pp. 368–375). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Phillips, M. (2010). Counterurbanisation and rural gentrification: An exploration of the terms. Population, Space and Place, 16(6), 539–558.

Poterba, J. M. (1983). Dividend taxes, corporate investment, and ‘Q’. Journal of Public Economics, 22(2), 135–167.

Statistic Sweden (2012). www.ssd.scb.se/databaser/makro/start.asp.

Stockdale, A. (2010). The diverse geographies of rural gentrification in Scotland. Journal of Rural Studies, 26(1), 31–40.

Stockdale, A., Finlay, A., & Short, D. (2000). Repopulation of rural Scotland: opportunities and threat. Journal of Rural Studies, 16(2), 243–257.

Swedner, H. (1968). Social struktur på landsbygden. In E. Dahlström (Ed.), Svensk samhällsstruktur i sociologisk belysning. Stockholm: Svenska Bokförlaget.

The Royal Bank of Scotland Group (2006). www.rbs.co.uk/firsthome.

Turner, B. (1995). What determines regional house prices in Sweden?—a cross section analysis. Scandinavian Housing and Planning Research, 12(3), 155–163.

Walks, R. A., & Maaranen, R. (2008). Gentrification, social mix, and social polarization: Testing the linkages in large Canadian cities. Urban Geography, 29(4), 293–326.

White, H. T. (2010). Property report October 2010.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank a number of persons for comments on an earlier draft of this paper. These persons are: Terry Hartig, Viggo Nordvik, Bo Söderberg and Terje Wessel. Thanks finally to referees for useful comments. This research was supported by The Swedish Research Council Formas.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Turner, L.M. Hunting for hotspots in the countryside of Northern Sweden. J Hous and the Built Environ 28, 237–255 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-012-9304-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-012-9304-7