Abstract

This paper reconsiders the fertility of historical social groups by accounting for singleness and childlessness. We find that the middle class had the highest reproductive success during England’s early industrial development. In light of the greater propensity of the middle class to invest in human capital, the rise in the prevalence of these traits in the population could have been instrumental to England’s economic success. Unlike earlier results about the survival of the richest, the paper shows that the reproductive success of the rich (and also the poor) were lower than that of the middle class, once accounting for singleness and childlessness. Hence, the prosperity of England over this period can be attributed to the increase in the prevalence of middle-class traits rather than those of the upper (or lower) class.

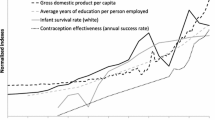

Data from Table F.1

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.Notes

As is clear in our demographic measures below, farmers are often an outlier group. We suspect that farmers organised themselves differently with regards to family planning than other segments of society for two reasons. They were much more closely affected by inheritance rules and the division of farm land between offspring, and as food suppliers they responded in the opposite manner to variations in food prices than all other groups who were food demanders.

We also ran other models with a greater number of time periods, one for each decade, but this did not influence our results.

The Cox proportional hazard model assumes, as its name indicates, that the hazard rate is shifted proportionately by the control variables. It implies that the survival functions for different social classes change proportionately and do not, for instance, cross each other. One test of the proportionality assumption (by Grambsch and Therneau (1994)) is obtained by computing, for each control variable, the scaled Schoenfeld residual, and by correlating it with a transformation of time (Hosmer and Lemeshow 1999, pp. 197–205; Schoenfeld 1982); proportionality is rejected if the correlation is statistically significant. In the case of our regression, the correlations are respectively 0.01 (Husbandmen), 0.01 (Craftsmen), 0.00 (Traders), -0.02 (Farmers), -0.00 (Upper class), and none of them is statistically different from zero.

We tested for regional variation in the marriage rates by grouping our parishes into three regions: North, Midlands and South. The upper classes had lower risks of marriage in all regions and statistically signicant differences in the Midlands and South. However, the gradient appears to hold across all regions (not reported).

Note that childbirth outside of wedlock was banned by the Church of England, and that illegitimate births, therefore, were rare ranging from 1.2 to 6.0% of births across our period (Wrigley et al. 1997, p. 224).

Leridon (2008) measures natural sterility in the Henry database for rural eighteenth century France when fertility control was ineffective. Restricting the sample to couples where the husband and the wife were still living together at age 50, 3.7% of women who married at age 20–24 remained childless.

We also test for proportionality here. The correlation between the scaled Schoenfeld residual and transformation of time are respectively 0.01 (Husbandmen), 0.00 (Craftsmen), 0.01 (Traders), 0.00 (Farmers), 0.03 (Upper class), and none of them is statistically different from zero, but for the Upper class. In addition to the proportionality assumption, it is also possible to test the assumption of the Cox model that censoring is independent from survival time. We have reasons to believe that it might be violated in the case of childlessness, as sterility and death have common unobserved determinants. We consider this issue in Appendix I, using the method proposed by Jackson et al. (2014) and find that it is not important for our results.

Again, we tested for regional variation in the childlessness rates by grouping our parishes into three regions: North, Midlands and South. The upper classes had lower risks of first birth in all regions but the differences were only statistically significant in the South. However, the gradient appears to hold across all regions (not reported).

The proportionality of the hazard rates is less clearly supported for the birth estimations than for the two extensive margins. Among the 63 coefficients in Table 4, proportionality is rejected in 26 cases (at the 5% level). However, this non-proportionality is not overly concerning because we are estimating the parity progression ratios over a short period of time (the cumulated hazard over 10 years rather than 30 years for marriage rates), and non-proportionality is less likely to be an issue over short time intervals (Bellera et al. 2010).

Moreover, the proportionality of hazards is never rejected.

We break the margins down further in Appendix D. This gradient also matches what one would find from a simple count of the number of children surviving to women sorted by the woman’s father’s occupation (see Appendix E.

We use the imputation method described in the next section (Sect. 4.6) to aggregate the uncertainty around the estimates for the four margins estimated above.

One might also wonder what would happen if those with unknown occupations were able to be assigned to their correct occupational categories. The unknown category has lower net reproduction than the other groups. Part of this is driven by the sources of occupations, which leads us to underestimate births and overestimate childlessness for that group, and is discussed at length in Sect. 5.3 and Appendix L. If we assume that the vast majority of the unknown were lower classes and reallocate all of the unknown into the lower class category, the net reproduction of the lower classes becomes statistically lower than both the middle and upper classes. However, the middle classes would still have far higher fertility than the upper classes, which is what is important for our story. The hump-shaped gradient would only become more accentuated.

Note that we do not lose any parishes in this robustness check because the parishes with data after 1780 all have starting dates before 1680. Thus, there are 26 parishes in all of the analysis.

We are not surprised that women have a slightly higher emigration rate than men in this case. We are mostly measuring migration over very small distances, given that a migrant is simply someone who leaves their parish of birth. We would not be surprised, then, if relatively few women migrated long distances and most women migrants simply moved into their husband’s parish nearby. As such, our findings do not challenge the common understanding that men have a higher propensity to emigrate.

See Appendix D and Figure D.1 for more detail.

References

Aaronson, D., Lange, F., & Mazumder, B. (2014). Fertility transitions along the extensive and intensive margins. American Economic Review, 104(11), 3701–24.

Althaus, P. G. (1980). Differential fertility and economic growth. Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswissenschaft / Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, 136(2), 309–326.

Anderson, M. (1990). The social implications of demographic change. In F. M. L. Thompson (Ed.), The Cambridge Social History of Britain, 1750–1950 (Vol. 2, pp. 1–70). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Armstrong, W. A. (1972). The use of information about occupation. In E. A. Wrigley (Ed.), Nineteenth-century society: Essays in the use of quantitative methods for the study of social data (pp. 191–310). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ashraf, Q., & Galor, O. (2011). Dynamics and stagnation in the Malthusian epoch. American Economic Review, 101(5), 2003–2041.

Bardet, J.-P. (1983). Rouen au XVII \(^e\) et XVIII \(^e\) siècles. Paris: SEDES.

Baudin, T., de la Croix, D., & Gobbi, P. E. (2015). Fertility and childlessness in the US. American Economic Review, 105, 1852–1882.

Baudin, T., de la Croix, D., & Gobbi, P. E. (2020). Endogenous childlessness and stages of development. Journal of the European Economic Association (forthcoming).

Bellera, C. A., MacGrogan, G., Debled, M., de Lara, C. T., Brouste, V., & Mathoulin-Pélissier, S. (2010). Variables with time-varying effects and the Cox model: some statistical concepts illustrated with a prognostic factor study in breast cancer. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 10(1), 20.

Belsey, M. A. (1976). The epidemiology of infertility: a review with particular reference to sub-Saharan Africa. Bulletin of the World Health Organization (WHO), 54(3), 319–341.

Bengtsson, T., & Dribe, M. (2006). Deliberate control in a natural fertility population: Southern Sweden, 1766–1864. Demography, 43(4), 727–746.

Blackstone, W., & Kerr, R. M. N. (1896). The student’s blackstone: Being the commentaries on the Laws of England of Sir William Blackstone. London: Reeves and Turner.

Boberg-Fazlic, N., Sharp, P., & Weisdorf, J. (2011). Survival of the richest? Social status, fertility and social mobility in England 1541–1824. European Review of Economic History, 15, 365–392.

Bowles, S. (2007). Genetically capitalist? Science, 318(5849), 394–396.

Cheneys. (1967). Cheneys of Banbury, 1767–1967. Cheneys & Sons.

Cinnirella, F., Klemp, M., & Weisdorf, J. (2017). Malthus in the bedroom: Birth spacing as birth control in pre-transition England. Demography, 54(2), 413–436.

Clark, G. (2007). A farewell to alms: A brief economic history of the world. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Clark, G., & Cummins, N. (2015). Malthus to modernity: Wealth, status, and fertility in England, 1500–1879. Journal of Population Economics, 28(1), 3–29.

Clark, G., & Hamilton, G. (2006). Survival of the richest: The Malthusian mechanism in Pre-Industrial England. The Journal of Economic History, 66(3), 1–30.

Clark, P. (1979). Migration in England during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Past & Present, 83, 57–90.

Cressy, D. (1981). Levels of illiteracy in England, 1530–1730. In H. A. Graff (Ed.), Literacy and social development in the west: A reader (pp. 105–124). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Crouzet, F. (1985). The first industrialists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

De Moor, T., & Van Zanden, J. L. (2010). Girl power: The European marriage pattern and labour markets in the North Sea region in the late medieval and early modern period. Economic History Review, 63(1), 1–33.

de la Croix, D. (2012). Fertility, education, growth, and sustainability. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

de la Croix, D., & Brée, S. (2019). Key forces behind the decline of fertility: Lessons from childlessness in rouen before the industrial revolution. Cliometrica, 13(1), 25–54.

de la Croix, D., & Doepke, M. (2003). Inequality and growth: Why differential fertility matters. American Economic Review, 93(4), 1091–1103.

de la Croix, D., Doepke, M., & Mokyr, J. (2018). Clans, guilds, and markets: Apprenticeship institutions and growth in the Pre-Industrial Economy. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133, 1–70.

Dennison, T., & Ogilvie, S. (2014). Does the European marriage pattern explain economic growth? The Journal of Economic History, 74(03), 651–693.

de Pleijt, A. M. (2018). Human capital formation in the long run: Evidence from average years of schooling in England, 1300–1900. Cliometrica, 12(1), 99–126.

de Pleijt, A. M., Nuvolari, A., & Weisdorf, J. (2019). Human Capital formation during the first industrial revolution: Evidence from the use of steam engines. Journal of the European Economic Association (early view).

Doepke, M., & Zilibotti, F. (2008). Occupational choice and the spirit of capitalism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(2), 747–793.

Feeney, G. (1986). Period parity progression measures of fertility in Japan. NUPRI Research Paper Series 35.

Fildes, V. A. (1986). Breasts, bottles and babies: A history of infant feeding. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Foreman-Peck, J. (2011). The Western European marriage pattern and economic development. Explorations in Economic History, 48(2), 292–309.

Froide, A. M. (2005). Never married: Singlewomen in early modern England. Cambridge: Oxford University Press.

Galor, O. (2012). Unified growth theory. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Galor, O., & Klemp, M. (2019). Human genealogy reveals selective advantge to moderate fecundity. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 3, 853–857.

Galor, O., & Michalopoulos, S. (2012). Evolution and the growth process: Natural selection of entrepreneurial traits. Journal of Economic Theory, 147(2), 759–780.

Galor, O., & Moav, O. (2001). Evolution and growth. European Economic Review, 45(4–6), 718–729.

Galor, O., & Moav, O. (2002). Natural selection and the origin of economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(4), 1133–1191.

Gobbi, P. E. (2013). A model of voluntary childlessness. Journal of Population Economics, 26(3), 963–982.

Gobbi, P. E., & Goñi, M. (2016). Childless aristocrats. Fertility, inheritance, and persistent inequality in Britain (1550–1950). unpublished.

Goñi, M. (2015). Kissing cousins. Estimating the causal effect of consanguinity on fertility using evidence from the London Season. unpublished.

Grambsch, P. M., & Therneau, T. M. (1994). Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika, 81(3), 515–526.

Hajnal, J. (1965). European marriage patterns in perspective. In D. E. Eversley & D. V. Glass (Eds.), Population in history: Essays in historical demography (pp. 101–43). Chicago: Chicago Illinois Aldine Publishing Company.

Henry, L. (1953). Fécondité des Mariages - Nouvelle méthode de mesure. Paris: Presses Universitaire de France.

Holcombe, L. (1983). Wives and property. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Hollingsworth, T. H. (1965). The demography of the British peerage. London: Population Investigation Committee, LSE.

Hosmer, D. W., & Lemeshow, S. (1999). Applied survival analysis: Regression modelling of time to event data. New York: Wiley.

Jackson, D., White, I., Seaman, S., Evans, H., Baisleyb, K., & Carpenter, J. (2014). Relaxing the independent censoring assumption in the Cox proportional hazards model using multiple imputation. Statistics in Medicine, 33, 4681–4694.

Jeub, U. N. (1993). Parish records: 19th century ecclesiastical registers. Umeå: Demografiska databasen, Univ.

Kelly, M., & Gráda, C. Ó. (2012). The preventive check in medieval and Preindustrial England. The Journal of Economic History, 72(04), 1015–1035.

Klemp, M., Minns, C., Wallis, P., & Weisdorf, J. (2013). Picking winners? The effect of birth order and migration on parental human capital investments in pre-modern England. European Review of Economic History, 17(2), 210–232.

Landers, J. (1993). Death and the metropolis: Studies in the demographic history of London, 1670–1830 (Vol. 20). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lee, J., Feng, W., & Li, B. (2000). Population, poverty, and subsistence in China, 1700–2000. In T. Bengtsson & O. Saito (Eds.), Population and economy: From hunger to modern economic growth (pp. 73–109). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Leridon, H. (2008). A new estimate of permanent sterility by age: Sterility defined as the inability to conceive. Population Studies, 62(1), 15–24.

Leunig, T., Minns, C., & Wallis, P. (2011). Networks in the premodern economy: The market for London apprenticeships, 1600–1749. The Journal of Economic History, 71(2), 413–443.

Livi-Bacci, M. (1986). Social group forerunners of fertility control in Europe. In A. Coale & S. C. Watkins (Eds.), The decline of fertility in Europe (pp. 182–200). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Long, J. (2013). The surprising social mobility of Victorian Britain. European Review of Economic History, 17(1), 1–23.

Malthus, T. R. (1798). An essay on the principle of population. London: Johnson.

Minns, C., & Wallis, P. (2012). Rules and reality: Quantifying the practice of apprenticeship in early modern England. The Economic History Review, 65(2), 556–579.

Mokyr, J. (2005). Long-term economic growth and the history of technology. In P. Aghion & S. N. Durlauf (Eds.), Handbook of economic growth (Vol. 1, pp. 1113–1180). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Parascandola, J. (2008). Sex, sin, and science: A history of syphilis in America. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group.

Ruggles, S. (1992). Migration, marriage, and mortality: Correcting sources of bias in English family reconstitutions. Population Studies, 46(3), 507–522.

Schoenfeld, D. (1982). Partial residuals for the proportional hazards regression model. Biometrika, 69(1), 239–241.

Schofield, R. (1985). English marriage patterns revisited. Journal of Family History, 10, 2–20.

Schofield, R. S. (1981). Dimensions of illiteracy in England, 1750–1850. In H. A. Graff (Ed.), Literacy and social development in the West: A reader (pp. 201–213). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shaw-Taylor, L., & Wrigley, E. A. (2014). Occupational structure and population change. In J. H. R. Floud & P. Johnson (Eds.), The Cambridge economic history of modern Britain: Volume 1, Industrialisation, 1700–1870 (pp. 53–88). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Skirbekk, V., et al. (2008). Fertility trends by social status. Demographic Research, 18(5), 145–180.

Squicciarini, M. P., & Voigtländer, N. (2015). Human capital and industrialization: Evidence from the age of enlightenment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(4), 1825–1883.

Stone, L. (1979). The family sex and marriage: In England 1500–1800. New York: Harper and Row.

Szreter, S. (2014). The prevalence of Syphilis in England and Wales on the eve of the great war: Re-visiting the estimates of the Royal Commission on Venereal Diseases 1913–1916. Social History of Medicine, 27(3), 508–529.

Szreter, S. (2017). Treatment rates for the pox in early modern England: A comparative estimate of the prevalence of syphilis in the city of Chester and its rural vicinity in the 1770s. Continuity and Change, 32(2), 183–223.

Van de Walle, E., & Van de Walle, F. (1972). Allaitement, stérilité et contraception: les opinions jusqu’au XIXe siècle. Population, 27(4), 685–701.

Van Leeuwen, M. H. D., & Maas, I. (2011). HISCLASS: A historical international social class scheme. Leuven: Universitaire Pers Leuven.

Vogl, T. (2016). Differential fertility, human capital, and development. Review of Economic Studies, 83, 365–401.

Voigtländer, N., & Voth, H.-J. (2013). The three horsemen of riches: Plague, war, and urbanization in Early Modern Europe. Review of Economic Studies, 80(2), 774–811.

Wallis, P., & Webb, C. (2011). The education and training of gentry sons in early modern England. Social History, 36(1), 36–53.

Weir, D. R. (1984). Rather never than late: celibacy and age at marriage in English cohort fertility, 1541–1871. Journal of Family History, 9(04), 340–54.

Wrigley, E. A. (1966). Family reconstitution. In D. E. C. Eversley, P. Laslett, & E. A. Wrigley (Eds.), An introduction to english historical demography: From the sixteenth to the nineteenth century (pp. 96–159). London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Wrigley, E. A. (1994). The effect of migration on the estimation of marriage age in family reconstitution studies. Population Studies, 48(1), 81–97.

Wrigley, E. A., Davies, R. S., Oeppen, J., & Schofield, R. (1997). English population history from family reconstitution: 1580–1837. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wrigley, E. A., & Schofield, R. (1981). The population history of England 1541–1871: A reconstruction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgements

David de la Croix acknowledges the financial support of the project ARC 15/19-063 of the Belgian French speaking Community. We thank Gregory Clark, Neil Cummins, Oded Galor, James Kung, Carol Shiue, Joachim Voth, Patrick Wallis and participants at the workshops on “The importance of Elites and their demography for Knowledge and Development” (UCLouvain, 2016), “Deep-Rooted Factors in Comparative Development” (Brown, 2017) and the seminar Economics and History (Marseilles, 2017) for comments on an earlier draft. An earlier version of this paper circulated as “Decessit sine prole”—Childlessness, Celibacy, and Survival of the Richest in Pre-Industrial England.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de la Croix, D., Schneider, E.B. & Weisdorf, J. Childlessness, celibacy and net fertility in pre-industrial England: the middle-class evolutionary advantage. J Econ Growth 24, 223–256 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-019-09170-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-019-09170-6

Keywords

- Fertility

- Marriage

- Childlessness

- European marriage pattern

- Industrial revolution

- Evolutionary advantage

- Social class