Abstract

During humanitarian crises, a large amount of information is circulated in a short period of time, either to withstand or respond to such crises. Such crises also give rise to misinformation that spreads within and outside the affected community. Such misinformation may result in information harms that can generate serious short term or long-term consequences. In the context of humanitarian crises, we propose a synthesis of misinformation harms and assess people’s perception of harm based on their work experience in the crisis response arena or their direct exposure to crises.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In humanitarian crises where a community faces large scale dangers, the affected people seek information that can help respond to such crises. However, in a short period of time, official and legitimate sources of the governments or news organizations normally cannot offer enough confirmed/verified information, pushing the community to consume information mainly through fast acting social media channels (Oh et al. 2013; h, 2015). Here social media can play a vital role with many active users uploading real time data about the crises (Holdeman 2018). However, social media is often the source of widespread misinformation (Gupta et al. 2013; Holdeman 2018; Maddock et al. 2015; Rajdev 2015). Facebook, WhatsApp and Twitter have been identified as social media platforms that spread most misinformation in crises (Nealon 2017; Pang and Ng 2017).

Research that focuses on misinformation harms has gained attention in the recent past. Agrafiotis et al. (2018), Elliott (2019) and Ohlhausen (2017) discuss misinformation harms, but not including humanitarian crises. Other scholars have addressed disinformation occurring during the COVID 19 pandemic (Love et al. 2020; Motta et al. 2020; Ma et al. 2020). Yet, to the best of our knowledge, there is no research that systematically examines people’s perception of the effects or consequences of misinformation in terms of harm during different types of humanitarian crises and in terms of differences in the perception of affected people or the larger community.

This paper fills the gap by developing a systematic synthesis of harms from misinformation as applied to humanitarian crisis contexts and investigates aspects of such harms. We use the synthesis in two chosen scenarios of crises misinformation. We present a visualization of the harms and test for significant differences between perceptions of harms between those working in the crisis response arena and those who are not as well as those affected by the crisis and those who are not. Thus, this paper contributes to the gap in the literature regarding misinformation harms and perceptions of such harms.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: The next section reviews the literature. Subsequently, we extract information and conduct surveys and analyze data to examine harms from misinformation during humanitarian crises. In the final section, we include a discussion and conclusion of the paper.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Misinformation and Misinformation Harms

Misinformation is incorrect information which can seem to be legitimate initially (Holdeman 2018) but can mislead and create harmful effects to the individual and the community (Pang and Ng 2017). Love et al. (2020) have identified that misinformation propagation can deepen harmful or deadly effects on people. Motta et al. (2020) have showed that misinformation spreading through right-leaning media shaped public misleading beliefs and eventually lead to distrust in media. They have also reported that “even seemingly innocuous [misinformation] from relied-upon media sources may lead individuals either into a false sense of security or lead others to ignore government recommendations” (p. 336). Misinformation harm has also been shown to range from hundreds of fatalities (Love et al. 2020). We stress on the following definition of misinformation harms: injuries that are a result of damages caused by misinformation (Bostrom 2011; Sandvik et al. 2017).

Prior literature on misinformation harms during humanitarian crises is scarce (Tran et al. 2019). Agrafiotis et al. (2018) created a structural taxonomy of harms in the context of organizations rather than in the context of humanitarian crises. They defined five main categories of harms and their sub categories, including physical or digital harms, economic harms, psychology harms, reputational harms, and social or societal harms. The harms were considered based on the view of organizations. In addition, Ohlhausen (2017) classified five groups of harms (FTC Informational Injury Workshop Report, 2018). Her taxonomy of injuries includes deception injuries, financial injuries, health or safety injuries, unwarranted intrusion injuries, and reputational injuries. Similarly, Elliott (2019) expounded on 5 categories, including physical harms, psychological or emotional harms, financial harms and reputation harms. He also mentioned about short-term and long-term harms. In this paper we draw from this work and adapt it to crisis context.

2.2 Misinformation Harms in Humanitarian Crises

Social media is an indispensable part of crisis response. It is utilized by the authorities for reporting real-time developments on the ground through breaking news and headline reporting. Social media has garnered public attention as a communication tool during crisis situations. However, the success of social media has been short-lived owing to the problem of misinformation.

Several studies have investigated the misinformation in crisis context (see Table 1). In the context of health crises, the anti-vaccination misinformation situations that expound on unproven risks and side effects or the inability of the immune system to respond to the viruses and bacteria have damaged public confidence in vaccination resulting in decline in vaccination and letting the community become exposed to diseases such as measles-mumps-rubella, hepatitis B, and H1N1 (Peretti-Watel et al. 2014). In addition, in the crisis of Zika virus in 2016, claims about the cause (genetically modified mosquitoes), severity (Zika virus symptoms are similar to seasonal flu), immunity (Americans are immune to the virus) and prevention (coffee can keep Zika mosquitoes away) caused problems for efforts to fight the dangerous infectious disease that resulted in people’s health being at risk (Ghenai and Mejova 2017, p. 3). Dredze et al. (2016) have attributed misinformation in social media to uncertainty regarding the origin of the message. Jamison et al. (2020) have discussed the role of Facebook ads in shaping misinformed views about vaccination among people.

In the context of natural crises, such as hurricane Sandy, Gupta et al. (2013) investigated spread of misinformation-filled messages. They concluded that there were very few original misinformation messages and that the majority of these messages were shared messages. Rajdev and Lee (2015) examined the behaviors of malicious users posting misinformation messages and concluded that malicious users had lesser number of favorite tweets compared to legitimate. Nealon (2017) reported that false information lead to unnecessary fears on the one hand and false expectations on the other, which severely affected evacuation decisions and support from authorities during hurricane Harvey and Irma. Similarly, misinformation about Louisiana floods in 2006 from Facebook messages and posts confused FEMA (March 2016 floods) and the American Red Cross (Summer floods) with information overload (Holdeman 2018).

Prior research has examined 15 types of harms related to crisis misinformation, including life, injury, income, business, emotion, trust, reputation, discrimination, connection, isolation, safety, access, privacy, decision and confusion harms (see Table 2).

There is recent research on Twitter social media users that address certain types of misinformation and their harms, such as the use of house cleaners as COVID 19 virus treatments (Chary et al. 2020) or “vaccine misconceptions” during Zika virus outbreak (Dredze et al. 2016). Additionally, (Motta et al. 2020) have examined “mentions” from online users that are related to misinformation harms on platforms such as Media Cloud in the context of the COVID 19 pandemic. However, few researchers have systematically considered the consequences from misinformation as might be perceived by either people from different backgrounds or different groups of affected people such as “patients” (Love et al. 2020) or “medical students and hospital workers” (Ma et al. 2020) in such a healthcare crisis like COVID 19 pandemic.

To ensure enriched quality of data (Love et al. 2020; Ma et al. 2020), in this paper, we have recruited participants that have knowledge and experience as well as exposure to the actual context of that topic. We have surveyed (Agrafiotis et al. 2018) participants that are victims of the crises (or referred to in this paper as “victims); and (Alexander 2018) participants that have existing crisis related working experience (referred to as “crisis responders”). We believe that victims can provide first-hand organic insight into perceptions of harms based on their own experience facing crises’ hazards and vulnerabilities. In addition, the crisis responders will have in depth knowledge and understanding about harm likelihood and impact as a result of their routine work that aims to mitigate or minimize possible immediate, short term or long term effects of emergencies as well as to help the community of victims and their situations to recover or reconstitute.

While various researchers have recently started addressing misinformation harms in specific contexts, there are several gaps in the literature that need to be considered. First, the harm identified are typically anecdotal in nature (Chary et al. 2020). Second, there are limited studies that systematically investigate different types of harms associated with the humanitarian crises. Third, there is scant research that addresses harm perceptions of people with varying crisis experience. Finally, majority of the research focuses on misinformation harm identification, rather than harm assessment. This paper fills these gaps.

Therefore, this paper (Agrafiotis et al. 2018) establishes a synthesis of misinformation harms that are applicable to the context of humanitarian crises, and (Alexander 2018) examines how people perceive misinformation harms in crises. The findings are expected to not only contribute to the understanding of perceived harms of misinformation during humanitarian crises contexts but also derive practical implications to stakeholders such as crises first responders, governmental organizations and social media platforms in efforts of minimize effects of misinformation toward the victims.

3 Methodology

3.1 Details of Survey

To examine misinformation harms, we conducted a survey to obtain judgements of people regarding their perceptions of harm from misinformation during crisis situations (Park et al. 2006). The survey was approved by IRB (Institutional Review Board) at a southern university in the U. S. It was designed using Qualtrics.Footnote 1 The survey was distributed through Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk).Footnote 2

We chose two scenarios, anti-vaccination and hurricane, that exhibited the following criteria: (Agrafiotis et al. 2018) popularity and familiarity: scenario details were widely known or were reported in various news outlets; and (Alexander 2018) diversity: the scenarios had different characteristics and captured different types of harms of misinformation in crises. The resulting scenarios are listed in Table 3: (Agrafiotis et al. 2018) anti vaccination crisis with overload of and confusing misinformation, and (Alexander 2018) Hurricane Harvey 2017 disaster with the wrong claim of immigration status check..

The survey was conducted in three rounds: The first round was a screening survey to filter participants that were victims and/or crisis responders, including those in firefighter departments, police departments, Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the Red Cross, or hospitals and other healthcare organizations. We ensured the reliability of participants’ claim that they were victims or crisis responders by asking them to list from 3 to 5 key steps they had performed to handle crisis situations. In this round, we asked for 400 responses from participants in the U. S. We retained 273 participants (68.25%) who had appropriate responses.

The second round was constructed to filter the 273 participants based on their familiarity with hurricane Harvey or anti-vaccination crises, or whether they had been involved in similar situations (see Table 3). Familiarity with the scenarios was measured on a Likert scale from 1 to 5. We retained 183 participants (67.03%) who had familiarity with the crisis situations at hand.

In the third round, we sent harm perception questionnaires to the 183 participants. They were asked to give judgements about the 15 harms listed in Table 2 on two aspects: likelihood of happening, and the level of impacts or the perceived damages of the harms. The ratings on likelihood ranged from 0 to the highest level of 10. Out of 183 requested responses, we got 89 responses (48.63%).

3.2 Addressing Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) Data Quality Concerns

There have been debates about the quality and validity of studies conducted on MTurk. Although raising concerns about appropriateness and overall quality of MTurk workers’ responses, Cheung et al. (2017) has pointed out that MTurk responses passed various important validity tests. Importantly, most researchers agreed that MTurk workers and their responses are much more diverse than participants from other recruiting methods (Buhrmester et al. 2011; Casler et al. 2013; Heen et al. 2014; Majima et al. 2017; Sheehan 2018). We also applied various quality control measures as detailed below.

We only allowed people qualified as “Master,” someone with more than 90% previous approval rates to join. Further we used attention check questions (ACQ) to ensure that we got the best responses. Our records show high quality regarding those ACQs. All these steps are crucial to guarantee high quality and appropriateness of the research design.

4 Data Analysis

4.1 Overview

As we can see from Table 4, the 89 participants were well distributed between scenarios.

4.2 Examining Harms in Scenarios and Quadrants

In order to examine harms perceptions in the misinformation scenarios, we tracked differences on two main dimensions: likelihood and impact. We rescaled the 0–10 scale to −5 to +5 scale by subtracting 5 so that zero is the mid-point. This resulted in four quadrants as shown below:

-

Quadrant 1: negative likelihood and negative impact

-

Quadrant 2: negative likelihood and positive impact

-

Quadrant 3: positive likelihood and negative impact

-

Quadrant 4: positive likelihood and positive impact

Table 5 summarizes the likelihood and impact, and the associated quadrants for the 15 harms. The ratings vary between the scenarios.

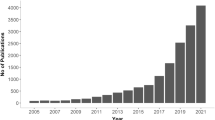

Table 5 yields the visualization as shown in Fig. 1. From Fig. 1, we can see that people perceived lower likelihood of harm for misinformation related to anti-vaccination while higher impact of harm for misinformation regarding hurricane scenario.

The most noticeable difference is in connection harm and isolation harm. Similar is the case with decision harm and confusion harm. This can be expected because confused undocumented immigrants may make wrong decision thereby not evacuating, and therefore may be left isolated. Furthermore, physical harms and emotional harms from scenario 2 are higher, suggesting that generally people care more about life threatening issues in crisis situations. Finally, we can also see that it seems financial harms and certain other harms related to general safety, services access and personal privacy do not have high scores, indicating that in such humanitarian contexts, those financial or safety harms are not prioritized because people care more about physical dangers and emotional harms.

One factor that can help explain this difference is the immediacy of response. In hurricane Harvey context, people are urged to act fast, and postponing evacuation due to misinformation about immigration status checks may lead to higher perception of harm. On the contrary, the need of vaccination can take months or years because its effects take more time to appear.

5 Post-hoc Analysis

5.1 Scenario Differences

In this section we test the significance of pairwise comparisons between the mean values of harm perceptions using Tukey test (Howell 2010). Tukey test investigates the significance of differences in means across the two scenarios in this study. The details of the results can be seen in Table 6. From the total 15 examined harms, we only report the differences that are statistically significant with p-values equal to or less than 5%.

From results in Table 6, we can see that the likelihood and impact of access harm, privacy harm and confusion harm differs between anti-vaccination and hurricane scenario. In addition, the likelihood of emotion harm, discrimination harm and connection harm as well as the impact of safety harm differs between the two scenarios. For example, the immigrants that decide not to evacuate during Hurricane Harvey disaster (S2) were more likely to face emotional harm due to interrupted social connections with friends or family members together with fears from dangers. Moreover, participants worry about general safety concerns owing to vast physical and life devastation potential of a hurricane.

5.2 Individual Differences

We further investigate the differences in harm perception between different participants with varying crisis experience and exposure.

We consider whether the perceived harms would be different between those working in the crisis response arena and those who are not. Crises related working experience is the experience dealing with rescuing victims (such as first responders or police officers), treating victims (such as doctors and nurses working for hospitals or clinics), or supporting victims of crises (such as staffs of emergency responses organizations like FEMA). We denote participants with such working experience as W1, and those without such experience as W0.

In addition, we also consider whether the perceived harms would be different between those affected by the crisis and those who are not (i.e. direct victims of the crisis). Direct victims are people who have been directly affected by any kind of crises, including natural and manmade crises. We denote participants that are direct victims as V1, and participants that are not direct victims as V0.

Table 7 showed the details of these considered groups and their distribution.

Tables 8 and 9 show the significant differences between groups of participants listed in Table 7. We consider the differences in terms of harms’ likelihood and impact. We report only the significant differences in Tables 8 and 9.

We notice that harms’ likelihood is positive across crisis experience groups. This implies that participants with crisis experience judged the likelihood of harms higher than the participants with no crisis experience because crisis responders have worked closely with the community impacted and as a result may be able to better able to identify potential harms that the opposite group may not be able to.

In addition, harms’ impact is negative across crisis exposure groups. This means that crisis victims reported lower impact of harms than their counterparts (non-victim participants). This is because victims have more realistic estimation while non-victims have exaggerated judgements that may be shaped by social media coverage.

We also notice that most of the significant differences in perceived harms belong to emotional or psychological harms such as trust, emotion, reputation or isolation harms because fear of immigration issues and physical damages from the hurricane can generate much higher levels of harms in S2 compared to the vaccination context of S1.

6 Conclusion

Humanitarian crises are situations in which people seek helpful information to find suitable solutions. Social media can act much faster than official information sources, but it comes with a price: exposure to misinformation that can create serious consequences. Many researchers have tried to tackle the situation by creating misinformation detection systems or algorithms, hypothesizing and testing the roles of behavioral characteristics of involved people, or finding the patterns of how misinformation can successfully spread and influence people. However, not much attention has been placed on categorizing the harms or impacts. This paper assesses misinformation harms in the context of humanitarian crises.

Moreover, by gathering judgements of people that have experience and exposure to crises through various rounds of survey, this study investigated the likelihood and the level of impacts of different harms derived from the literature as well as the individual differences associated with them.

These findings are expected to be beneficial not only for optimizing crisis response and recovery activities for prioritizing the use of resources, but also for future research studies to deepen and broaden such findings. The contributions of this research to both the practical side of benefiting the community or minimizing harms for victims and the academic size of forming a systematic background for humanitarian crises and emergency related researches are clearly significant.

There are certain limitations of this study. While we have tested how participants with and without crisis related working experience or victimization experience responded differently for likelihood and impacts of harms, we have not tested for specific types of working experience (such as police officers, first responders, doctors or nurses) or victimization exposure (such as direct or indirect victims). In addition, we have not examined the effects of demographics information (such as age, gender or income) that may influence the perceived harms. We propose that future research can extend this work in several ways. We recommend testing other types of crises in order to generalize findings reported in this paper.

References

Agrafiotis, I., Nurse, J. R., Goldsmith, M., Creese, S., & Upton, D. (2018). A taxonomy of cyber-harms: Defining the impacts of cyber-attacks and understanding how they propagate. Journal of Cybersecurity, 4(1), tyy006.

Alexander, K. (2018). What caused nearly 20,000 quakes at Oroville dam? Scientists weigh in on mystery”. Retrieved on 08/25/2019 from: https://www.sfchronicle.com/news/article/What-caused-nearly-20-000-quakes-at-Oroville-Dam-13473254.php

Bostrom, N. 2011. “Information hazards: A typology of potential harms from knowledge”. Review of Contemporary Philosophy, 10, 44–79. Retrieved on 07/01/2019 from http://search.proquest.com/docview/920893069/

Buhrmester, D. M., Kwang, N. T., & Gosling, D. S. (2011). Amazon's mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(1), 3–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691610393980.

Casler, K., Bickel, L., & Hackett, E. E. (2013). Separate but equal? A comparison of participants and data gathered via Amazon’s MTurk, social media, and face-to-face behavioral testing. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(6), 2156–2160.

Chary, M., Overbeek, D., Papadimoulis, A., Sheroff, A., & Burns, M. (2020). Geospatial correlation between covid-19 health misinformation on social media and poisoning with household cleaners. MedRxiv Preprint. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.30.20079657.

Cheung, H. J., Burns, K. D., Sinclair, R., & Sliter, M. (2017). Amazon mechanical Turk in organizational psychology: An evaluation and practical recommendations. Journal of Business and Psychology, 32(4), 347–361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-016-9458-5.

Dredze, M., Broniatowski, D. A., & Hilyard, K. M. (2016). Zika vaccine misconceptions: A social media analysis. Vaccine, 34(30), 3441–3442.

Elliott, D. (2019). Concept unwrapped – Causing harms. Copyright © 2019 ethics unwrapped - McCombs School of Business – The University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved on 02/15/2019 from: https://ethicsunwrapped.utexas.edu/video/causing-harm.

Ghenai, A., & Mejova, Y. 2017. Catching Zika fever: Application of crowdsourcing and machine learning for tracking health misinformation on twitter. arXiv.org.

Gupta, A., Lamba, H., Kumaraguru, P., Joshi, A. (2013). Faking sandy: Characterizing and identifying fake images on twitter during hurricane sandy. In Proceedings of the 22nd international conference on world wide web (pp. 729-736).

Heen, M. S., Lieberman, J. D., & Miethe, T. D. (2014). A comparison of different online sampling approaches for generating National Samples. UNLV – Center Crime Justice Policy, 1, 1–8 Research in brief. September 2014, CCJP 2014-01.

Holdeman, E. (2018). BLOG: Disaster zone: How to counter fake news during a disaster. Chicago: TCA Regional News.

Howell, C. H. (2010). “Scheffé test”. In: Encyclopedia of Research Design, pages: 1323-1325. Published by SAGE Knowledge. Subject: Research Design. Edited by: Neil J. Salkind. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412961288.n404.

Jamison, A. M., Broniatowski, D. A., Dredze, M., Wood-Doughty, Z., Khan, D., & Quinn, S. C. (2020). Vaccine-related advertising in the Facebook ad archive. Vaccine, 38(3), 512–520.

Love, J. S., Blumenberg, A., & Horowitz, Z. (2020). The parallel pandemic: Medical misinformation and COVID-19: Primum non nocere. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05897-w.

Ma, X., Vervoort, D., & Luc, J. G. (2020). When misinformation goes viral: Access to evidence-based information in the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Global Health science, 2(1), e13. https://doi.org/10.35500/jghs.2020.2.e13 pISSN 2671-6925·eISSN 2671-6933.

Maddock, J., Starbird, K., Al-Hassani, H., Sandoval, D., Orand, M., Mason, R. (2015). Characterizing online rumoring behavior using multi-dimensional signatures. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM conference on computer supported cooperative work & social computing (pp. 228–241). ACM.

Majima, Y., Nishiyama, K., Nishihara, A., & Hata, R. (2017). Conducting online behavioral research using crowdsourcing services in Japan. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00378.

McNamara, A. (2019). Facebook announces plan to combat anti-vaccine misinformation. Retrieved on 06/14/2019 from: https://www.thedailybeast.com/facebook-announces-plan-to-combat-vaccine-misinformation

Miller, C. A. (2019). Viral misinformation: Rise of 'anti-vaxxer' movement requires news literacy inoculation. USA today. Retrieved on 6/14/2019 from: https://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2019/05/03/measles-spread-viral-anti-vaxxer-misinformation-internet-literacy-news-column/3650914002/

Motta, M., Stecula, D., Farhart, C. (2020). How right-leaning media coverage of COVID-19 facilitated the spread of misinformation in the early stages of the pandemic in the US. Canadian Journal of Political Science/revue canadienne de science politique, pp.1-8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423920000396.

Nealon, C. (2017). False Tweets During Harvey, Irma Under Scrutiny by University At Buffalo Researchers. Washington, D.C: US Fed News Service, Including US State News [Washington, D.C]29. Sep 2017. Retrieved on 02/15/2019 from: http://www.buffalo.edu/news/releases/2017/09/044.html.

Newton, C. (2019). Instagram will begin blocking hashtags that return anti-vaccination misinformation. Retrieved on 06/14 from: https://www.theverge.com/2019/5/9/18553821/instagram-anti-vax-vaccines-hashtag-blocking-misinformation-hoaxes

Oh, O., Agrawal, M., & Rao, H. (2013). Community intelligence and social media services: A rumor theoretic analysis of tweets during social crises. MIS Quarterly, 37(2), 407–426.

Ohlhausen, M.K. (2017). Informational Injury in FTC Privacy and Data Security Cases. Retrieved on 02/15/2019 from: https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_statements/1255113/privacy_speech_mkohlhausen.pdf.

Pang, N., & Ng, J. (2017). Misinformation in a riot: A two-step flow view. Online Information Review, 41(4), 438–453.

Park, I., Lee, J., Upadhyaya, S. J., & Rao, H. R. (2006). Emerging issues for secure knowledge management-results of a Delphi study. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics - Part A: Systems and Humans, 36(3), 421–428. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSMCA.2006.871644

Peretti-Watel, P., Raude, J., Sagaon-Teyssier, L., Constant, A., Verger, P., & Beck, F. (2014). Attitudes toward vaccination and the H1N1 vaccine: Poor people’s unfounded fears or legitimate concerns of the elite? Social Science & Medicine, 109, 10–18.

Rajdev, M., & Lee, K. 2015. “Fake and spam messages: Detecting misinformation during natural disasters on social media”. In 2015 IEEE/WIC/ACM international conference on web intelligence and intelligent agent technology (WI-IAT) (Vol. 1, pp. 17-20). IEEE.

Sandvik, K., Jacobsen, K., & McDonald, S. (2017). Do no harm: A taxonomy of the challenges of humanitarian experimentation, 99(904), 319–344. https://doi.org/10.1017/S181638311700042X.

Sheehan, B. K. (2018). Crowdsourcing research: Data collection with Amazon’s mechanical Turk. Communication Monographs, 85(1), 140–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2017.1342043.

Tran, T., Valecha, R., Rao, H. R. and Rad, P. (2019). Misinformation harms during crises: When the human and machine loops interact," 2019 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Los Angeles, 2019, pp. 4644–4646.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tran, T., Valecha, R., Rad, P. et al. An Investigation of Misinformation Harms Related to Social Media during Two Humanitarian Crises. Inf Syst Front 23, 931–939 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-020-10088-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-020-10088-3