Abstract

This article provides a first step towards a better theoretical and empirical knowledge of the emerging arena of transnational climate governance. The need for such a re-conceptualization emerges from the increasing relevance of non-state and transnational approaches towards climate change mitigation at a time when the intergovernmental negotiation process has to overcome substantial stalemate and the international arena becomes increasingly fragmented. Based on a brief discussion of the increasing trend towards transnationalization and functional segmentation of the global climate governance arena, we argue that a remapping of climate governance is necessary and needs to take into account different spheres of authority beyond the public and international. Hence, we provide a brief analysis of how the public/private divide has been conceptualized in Political Science and International Relations. Subsequently, we analyse the emerging transnational climate governance arena. Analytically, we distinguish between different manifestations of transnational climate governance on a continuum ranging from delegated and shared public–private authority to fully non-state and private responses to the climate problem. We suggest that our remapping exercise presented in this article can be a useful starting point for future research on the role and relevance of transnational approaches to the global climate crisis.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Scientific evidence indicates with increasing certainty that current changes in the earth’s climate system are happening as a result of human agency, and that they are taking place at an accelerated pace (IPCC 2007; Stern 2007). While the problem of anthropogenic climate change is gaining renewed attention in the media and the wider public,Footnote 1 the institutional architecture in place seems to be rather incapable of effectively addressing climate change. Within this context, the scientific community has so far not sufficiently reflected on one of the major trends in global environmental governance that increasingly gains relevance for global climate politics: the transnationalization of environmental governance (cf. Biermann and Pattberg 2008). The current transnationalization of global climate governance can be observed in phenomena such as private standard-setting initiatives for the carbon market (e.g. the Gold Standard), public–private governance networks that implement internationally agreed outcomes such as the Millennium Development Goals (e.g. The Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Partnership), public non-state networks that focus on mitigation (e.g. C40, a recent initiative of 40 global cities to curb their greenhouse gas emissions) and private networks that attempt to govern the climate arena through information disclosure and public awareness (e.g. the Carbon Disclosure Project).Footnote 2

More systematically, the transnationalizationFootnote 3 of climate governance refers to at least five empirical observations. First, global climate governance is marked by a proliferation of policies, such as the emissions trading system of the European Union (EU), the target-and-timetables approach of the Kyoto Protocol, the voluntary Asia-Pacific Partnership on Clean Development and Climate (APP) (van Asselt 2007), independent initiatives taken by some U.S. states, and the fast-growing voluntary carbon market. Second, global climate governance is marked by a mosaic of actors, including governments, civil society, science, business, and public non-state actors such as cities, and their interlinked political activities in this field.Footnote 4 Third, and as a consequence, global climate governance is marked by divergent polities and principles on how the overall architecture of climate governance should be structured: While some nations hope to maintain a universal approach towards climate governance, others seemingly work towards new forms of a more fragmented and flexible order that places more emphasis on hybrid and private mitigation policies (Biermann et al. 2007c). Fourth, and related to the above, the emerging carbon market is now increasingly fragmented, but with many interconnections. An important distinction can be made between compliance (or mandatory) markets and voluntary markets. Further, there are two major types of transactions of emissions reduction credits taking place: allowance-based transactions and project-based transactions. The former refers to the trading of issued allowances created and allocated by regulators under a cap-and-trade regime and in the latter are emission credits the result of a specific project in a baseline-and-credit system.

Finally, global climate governance is marked by a multiplication of functional interlinkages and communication channels, apparent in the observation that the future of global climate governance is currently negotiated in different and often non-synchronized discussion fora. While, for example, the future of the current climate regime and, in particular, its Kyoto Protocol is negotiated in the open-ended ad hoc working group (AWG), established at the first COP/MOP in 2005, the larger convention dialogue on “long-term cooperative action to address climate change” and the seminar of government experts’ (SOGE) current discussion on reducing deforestation in developing countries, other future strategies are discussed within the Gleneagles G8 plus 5 process, the Major Economies Meeting initiated by the U.S. Administration, and the APP.Footnote 5 In addition, the crucial role of business and other non-state actors in mitigating climate change is rarely reflected in the international negotiations.

In light of this growing complexity of global climate policy, we argue that an expansion of our analytical toolkit is both necessary and rewarding. We contend that the predominant perspective on global climate governance is biased and incomplete as it takes into account only the international arena of interstate negotiations, public policies and those non-state actors that try to influence international agreements. However, current developments in global climate governance are signs of the gradual institutionalization of a transnational public sphere in world politics, where the establishment of norms and rules and their subsequent implementation are only to a limited extent the result of public agency in the formal sense, but often the outcome of agency beyond the state.Footnote 6 Therefore, a more detailed mapping of the actors, mechanisms and systems of rules beyond the interstate system is necessary to appraise all potential options for an effective and equitable future global climate governance architecture.

We proceed in three steps. First, we provide a critical re-conceptualization of the public/private distinction in International Relations (IR) theory. Subsequently, we attempt a remapping of global climate governance by focusing on agency and architecture beyond the state. Empirically, we offer an overview of transnational approaches towards global climate governance, including governance through markets and governance through networks. Our cases are illustrations of our conceptual framework rather than an all-encompassing mapping of the field. Finally, we conclude with some lessons learned and a number of questions for future research in the field of transnational climate governance.

2 The public and the private ‘divide’

The distinction between the public and the private is a crucial ordering device in social life and it continues to shape much of the current debates surrounding various forms of governance. The following sections provide a brief portrayal of how the public and private have been conceptualized in the political science literature and indicate how it might be rethought. We will specifically sketch how the discipline of IR has historically worked with a rather crude approach to the public/private divide that is a direct result of its statist point of departure. However, there have been some significant reorientations in the literature that enable a less statist and more comprehensive remapping of global politics. While it is common to refer to a ‘divide’ or a ‘gap’ between the public and the private, such dichotomous thinking actually turns out to be not necessarily wrong but rather unhelpful when it comes to understanding how authority is being articulated and how governance is shaped through non-state actors in issue areas such as climate change.

2.1 The public and the private in political theory

In political theory the legacy of the Polis is pervasive. The Polis is the ancient Greek term for the city-state and refers to a rather small entity, independently governed, and composed of both rural and urban areas. There was only one city for each Polis and the members of the community, the citizens, identified themselves with common religion, language and costumes. The Greek word Politeia (government), derived from the term Polis, was used to describe the way city-states were ruled. It was Hanna Arendt who, with The Human Condition (1958), drew attention to the separation of Greek life into two realms: a public (the Polis) and a private (the household). Arendt, in a classic formulation, uses the Polis metaphorically and states that the Polis

“is not the city-state in its physical location; it is the organization of the people as it arises out of acting and speaking together, and its true space lies between people living together for this purpose, no matter where they happen to be” (Arendt 1958, p. 198).

Beacroft underscores the centrality of Arendt’s thinking for our conceptualization of politics: the “Greek model of the Polis remains relevant to political theory as it highlights the centrality of the public realm for political life as a way of speaking, acting and living between human beings” (Beacroft 2007, p. 42). For IR specifically, the equation of the public, the state and the territory has had fundamental implications for how we think of authority and governance. Authority, that is legitimate power, has been understood to exist only inside the Polis and, hence, outside the territory/state/public power has been considered ‘illegitimate’. It has therefore been difficult for IR to come to terms with non-state actors as a legitimate form of agency ‘beyond the state’ in world politics.

While political analysis and commentaries are accustomed to use the public (the state) and the private (the market) in a specific way, these concepts are more contested than usually acknowledged. In two essays, Bailey (2000, 2002) provides an historical overview of the public/private divide and shows that there is no essential ‘private’ or genuinely ‘public’. In ancient Greek civilization the public was the sphere of freedom and decision. Later on, Roman imperial and republican conceptualizations shifted the focus of the public from shared deliberation to absolute sovereignty. However, in any case, the private was merely residual and it was the public that was privileged as idea, concern and project. During the Middle Ages and the period of feudalism the public/private distinction faded. Kinship and networks of personal dependency made both the public and the private irrelevant as categories. However, the public/private distinction made a comeback with the rise of modernity and civil society, and through ideas such as sovereignty and citizenship. In a comprehensive fashion, Bailey (2002, p. 19) argues that

“the rise of bourgeois civil society, the spread of market-based social relations and legal-rational capitalism, and the growth of political representation and political democracy in the West all marked the next stages for change in the meanings of the public and private”.

Throughout history, the content and location of the private and the public has not been fixed. The private can refer to, inter alia, the family, the domestic, the personal, friendship and the self, while the public can refer to the state, civil society, the market and community. Hence, what is important here is that Bailey adopts an understanding of the public, not as that which is ‘the state’, but as that which is ‘collective’. Collective actors derived from civil society, the market and various communities become effectively public with a potential to govern people and issues. As we will see in a moment, this is an accord that harmonizes with recent writings on the public and private in world politics.

2.2 Public and private authority in world politics

Within the discipline of IR, by and large, the public has been equal to the state and the private has been equal to the non-state. The role of non-state actors was attracting scholarly interest in the early 1970s (e.g. Keohane and Nye 1972). The predominant focus of these studies was to account for the influence of non-state actors (mostly multinational corporations) on state behaviour in various issue areas. Keohane and Nye (1977) have later developed the theoretical model of “complex interdependence”, which portrays a world where transnational activity affects the states’ capacity to act, where the distinction between ‘high’ (security) and ‘low’ (trade) politics is obsolete, and where military force is seen, by and large, as ineffective.

By the mid-1980s, institutionalist thinking had shifted towards a functional theory of regimes (Keohane 1984) that could account for patterns of international cooperation (or the lack thereof). This theory provided the opportunity for Realism and Liberalism to unite in a shared ‘rationalist’ research programme that was premised on the condition of anarchy in the international system (i.e. authority seen as divided and separated territorially) and oriented towards investigating the conditions for international cooperation. This perspective became also influential for the way research on global environmental politics came to be conceptualized and it still continues to shape and inspire research in the field.Footnote 7

In a broad (critical) reflection on the regime approach to global environmental issues, Conca (2006, p. 21) argues that

“simply put, regimes are the vehicles of states. Because a codified international agreement lies at the heart of most processes of regime building, regimes internalize strong presumptions about state authority, the legitimacy of state actions, and the essential difference between governments and other collective agents.”

Therefore, given that global climate governance is increasingly transnationalizing, there is an urgent need to reconsider climate governance with regard to questions of authority.

Starting from a similar position, James Rosenau has emphasized the role of non-state actors and authority in world politics rather differently. Stressing that “governance without government” is present in many issue areas, Rosenau (1997) concluded that degrees of order are achieved through regime-building efforts and other rule-making activities without the presence of a state or a formal intergovernmental institution. The emergence of such new authority structures led Rosenau to identify two (separate) political worlds, one ‘state-centric’ consisting of ‘sovereignty-bound states’ and the other ‘multi-centric’ consisting of ‘sovereignty-free’ actors. As a result, Rosenau tries to account for non-state actors as more generic ‘spheres of authority’. Consequently, Rosenau (1997, p. 39) understands these spheres of authority as the building blocks of a new ontology where states are treated as only one of the many sources of authority.

In a similar vein, but with less focus on novelty and instead with a view on historic continuity, Ferguson and Mansbach (1996, 2004) have provided a comprehensive remapping of global politics in which authority is fragmented among polities with little hierarchical arrangement among them.

The shift in conceptualizing authority in world politics is most pronounced in two edited books, Private Authority in International Affairs (Cutler et al. 1999) and Private Authority in Global Governance (Hall and Biersteker 2002a). Hall and Biersteker contend that traditional approaches to international politics regard states not only as the principal actors, but also as the only legitimate actors. They argue that the equation of authority with government has for too long constrained an analysis of other forms of authority. But, in fact, the public does not need to equal the government:

“Being public does not, however, imply that a state or public institution must be involved or wielding authority, even though they might participate in recognizing it in certain situations. It does, however, imply that the social recognition of authority should be publicly expressed. This opens the possibility for the emergence of private, non-state based, or non-state legitimated authority” (Hall and Biersteker 2002b, p. 5).

Hence, the distinction between the state as the public domain and the non-state as the private domain is neither a helpful guide to where to find, and not to find, authority nor does it allow to make any claims about where authority should, or should not, be located. It seems now rather obvious that increasingly norms, rules, roles and responsibilities are becoming institutionalized beyond the confines of the state and the international society they construct. As Ruggie (2004, p. 521) has argued,

“the arena in which ‘the authoritative allocation of values in societies’ now takes place increasingly reaches beyond the confines of national boundaries, and a small, but growing fraction of norms and rules governing relations among social actors of all types (states, international agencies, firms, and of civil society) are based in and pursued through transnational channels and processes.”

Consequently, we define this emerging space of interactions, the related norms and rules and the resulting roles and responsibilities of actors within the field of climate change as a transnational arena of climate governance. The next section will explore this analytical space in more detail.

3 Remapping transnational climate governance

In contrast to a majority of scholars and policy makers who view global climate governance as predominantly determined by the authority of states, we argue for a conceptualization that is comprehensive enough to cover various ways in which authority is being articulated in relation to the climate issue.Footnote 8 One helpful approach is to distinguish between the source of authority and the mode of steering involved. Börzel and Risse (2005) propose a continuum of public, hybrid and private sources of authority on the constellation-axis and a continuum of hierarchical and non-hierarchical steering modes on the governance-axis. We can further distinguish these modes of governance into hierarchical top-down regulation, and non-hierarchical governance through markets and networks (cf. Mayntz 2004). In this respect, we understand approaches of global climate governance to be situated along a continuum ranging from international and public sources of authority to public–private or private interventions. Some are related to international agreements and norms and thus fall under a shadow of hierarchy (e.g. the European Emissions Trading Scheme), while others are situated in the realm of non-hierarchical steering without any overarching authority. For the purpose of this article, we focus on those approaches, policies and institutions that are situated beyond the purely international policy arena and thus constitute the emerging, and in many instances contested, arena of transnational climate governance. We provide examples of governance through markets and networks for public, hybrid and purely private sources of authority in Table 1.

In order to analyse this emerging arena, we draw on two concepts that help to assess the contribution of transnational climate policies to effectively address global climate change. First, the concept of agency beyond the state that focuses on the actor-dimension and the source of authority (horizontal axis), and second, the concept of architecture that highlights the generic governance principles, the institutional design and the institutional interlinkages of different modes of governance within and across issue areas (vertical axis).Footnote 9

The concept of agency beyond the state is useful in analyzing the contributions—positive as well as negative—of different actors to the problem of anthropogenic climate change.Footnote 10 In our reading, agency, understood as the capacity of individual and collective actors to change the course of events or the outcome of processes, is increasingly located in sites beyond the state and its international organizations. A number of actors deliberately form social institutions to address the problem of climate change without being forced, persuaded or funded by states and other public agencies. To limit our analysis, we exclude agency that is unconscious about itself (e.g. the unintended consequences of everyday activities), but include individual agency, as in the case of carbon neutrality.

The second analytical concept that we apply to the emerging transnational arena of global climate governance is architecture. According to Biermann (2007), architecture is defined as “the interlocking web of principles, institutions and practices that shape decisions by stakeholders at all levels”. Most research has hitherto been focused on single institutions. As a result, we today possess a fairly good understanding of the determinants of institutional effectiveness (cf. Miles et al. 2001; Victor et al. 1998). In comparison, however, the effectiveness of the overall institutional structure remains much less understood.

With regard to approaches that fall within our concept of transnational climate governance, an analytical distinction can be made between those that are still connected to and/or embedded in the international climate governance arena and those that predominantly emanate from private authority and are directed to private actors. The next sections will provide an empirical remapping of the current transnational climate governance arena, including both hybrid and private markets as well as public, hybrid and private networks.

3.1 Transnational climate governance through markets

With the successful negotiation and entry into force of the Kyoto Protocol, market mechanisms have become a cornerstone of the current climate governance architecture. The following sections discuss the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) as an example of hybrid authority and the concept of carbon neutrality as well as company- and industry-wide emissions trading schemes as illustrations of private authority in transnational climate governance.Footnote 11

3.1.1 The clean development mechanism: carbon commodification?

The main trend in climate change governance since the negotiations of the Kyoto Protocol (1997) has been the process of carbon commodification, i.e. the turning of carbon dioxide emissions reduction into commodities that can be bought and sold in a market. Markets for emissions reduction do not emerge spontaneously but have to be crafted by political decisions. The Clean Development Mechanism entered late in the Kyoto negotiations as part of three ‘flexible mechanisms’ that were supposed to make the provisions more agreeable to the U.S. As it turned out, the U.S. did not ratify the Protocol but the CDM has nonetheless been established as an important mode and node of climate governance. The CDM aims at providing low-cost emissions reductions to Annex 1 countries (developed countries with binding emission targets under the Kyoto protocol), while at the same time facilitating technology transfer, increasing the flow of capital from rich to poor countries, and providing sustainable development in developing countries. In simple terms, the CDM works “by paying developing countries to adopt lower-polluting technologies than they otherwise would” (Wara 2007, p. 595). Its relative success or failure depends on where you look.

As a market, CDM seems to be (after a slow start) able to provide significant volumes of emissions reduction for the carbon market. In May 2008, there were 3,498 CDM projects under validation and registration in the CDM project Pipeline (UNEP 2008). In 2007, 551 MtCO2eFootnote 12 for a value of 4,787 million Euros were transacted in the CDM market (Capoor and Ambrosi 2008). The CDM seems to deliver comparatively cost-effective reductions, but research suggests that neither does it deliver sustainable development (Rowlands 2001; Cosbey et al. 2006; Schneider 2007) nor does it contribute to investments in new infrastructure and technology (Ellis et al. 2007; Pearson 2007). This point is underlined in a large literature review of CDM and sustainable development: “the initial assumption of the synergy and win-win relationship between the dual aims of the CDM does not hold for many projects studied in the literature” (Olsen 2007, p. 64). However, since the market share of renewable energy, fuel switching and energy efficiency projects have risen from 14% in 2005 to 64% in 2007, the potential for a contribution to sustainable development has increased.

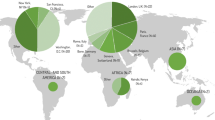

Overall, climate governance through the CDM is unevenly spread across the globe. Three countries (China, India and Brazil) account for two-thirds of the projects and, as regions, Latin America and the Asia and Pacific region host 96% of the projects. Africa has earlier been bypassed in the CDM investments flows, but has now somewhat risen to hold a market share of 5% of transacted volumes of Certified Emission Reduction (CER) even though the number of projects (74) is still rather low. To some observers, geographically unbalanced climate governance can be remedied through institutional redesign (Haites and Yamin 2000), through stricter interpretation of additionality (Hamwey 1998) or through different kinds of locally sensitive projects that connect to rural development strategies (Boyd et al. 2007). To other observers, redesign, stricter rules or new projects will not work as the CDM is fundamentally flawed. CDM is, in this perspective, a kind of new ‘carbon colonialism’ that only serve to legitimize rich countries’ overconsumption of the world’s resources (Bachram 2004).

The CDM is principally interesting because it exemplifies a broader contemporary turn in environmental policymaking towards market liberalism, flexibility and pluralism. The governance of the CDM involves agency beyond the state at different political levels and across various jurisdictions. Authority is delegated to a range of non-nation state actors and their responsibilities diverge in every step of the CDM project cycle, from project identification and design to validation, registration, monitoring and over to verification and certification, and, finally, to the issuance of CERs. The supreme authority over the CDM is shared among governments in the CDM Executive Board (EB) and difficult issues are negotiated and resolved under the climate convention. The EB is responsible for approval and registration of CDM projects, the issuance of CERs, and the accreditation of the ‘Designated Operational Entities’ (DOEs), which are independent third-party private actors involved in the validation and verification of CDM projects. At the national level, the Designated National Authority (DNA) is an entity governments are required to set up to approve potential CDM projects. Annex B governments are also involved in the CDM project cycle as investors and project initiators and host-country governments may also develop CDM projects on a unilateral basis. The private sector involves different types of actors such as CDM project proponents, consultants (that identify and design CDM projects, take care of documentation in relation to baseline and monitoring methodologies), carbon brokers (involved in the sale of CERs), carbon investment funds (bridge between sellers and buyers of CERs), and, importantly, DOEs. Multilateral organizations (such as the World Bank, UNIDO, UNDP, UNEP) appear frequently in CDM governance in various roles (e.g. providing technical advisory, capacity assistance, research/scientific advice and project finance). International organizations also set up carbon investment funds and purchase CERs on behalf of governments and corporations. It is likely that the roles and responsibilities of public and private actors in the CDM (or some similar market mechanism for sustainable development) will change when a new post-2012 climate governance architecture is agreed upon.

3.1.2 Voluntary carbon markets: The concept of carbon neutrality and corporate emissions trading

In 2006, Oxford University Press announced “carbon neutrality” to be the word of the year.Footnote 13 A well-deserved award, as the concept had received a lot of media attention when, for example, Coldplay in 2002 announced that they would plant 10,000 mango trees in southern India to offset the environmental impacts of their second album. The Rolling Stones claimed their tour in 2003 to be carbon neutral, and in 2004, one of the world’s largest banks, HSBC, became the first carbon neutral bank. Even the FIFA World Cup 2006 was announced as a carbon neutral event. ‘Carbon Neutrality’ refers to companies and individuals who ‘offset’ their carbon emissions by buying carbon credits that equal out their contribution to climate change. It is important to note that carbon offsetting can be carried out in two different ways that follow slightly different logics. One way is to buy emissions rights in a cap-and-trade market (such as the EU ETS) that, in theory, raise the price and hence reduce the demand for carbon. Whether the price actually rises depends on whether the buyer is in a position to influence the market. The other way follows the logic of the CDM and Joint Implementation, where carbon credits are generated through a certain project. The project could either remove emissions from the atmosphere (such as tree-planting projects) or reduce emissions indirectly (for example through fuel switching) when compared to a business as usual projection.

The last years have seen an explosion in carbon offset retailers that made a publication like “A Consumers Guide to Retail Carbon-Offset Providers” (2006) necessary. On the demand side, every week we can witness new entities (for example governments, travel magazines, airline companies, university departments) announcing their engagement in the voluntary market. Usually, the demand is to offset a certain activity but the trend is also spreading to products and services. In media, comments about this development range from “The Good, The Bad, The Ugly” (Brainard 2007). It is common to point at carbon offsetting as a modern form of selling indulgences that do not induce changes in lifestyles (Monbiot 2006; Revkin 2007). Debates have also drawn attention to the dubious quality of the offered offsets and to the lack of common standards (Robbins 2006; Harvey and Fidler 2007). Within a critical international political economy perspective, Larry Lohmann (2006) offers a comprehensive account of carbon offsetting as a new arena of conflict and contestation. In the same vein, the report “The Carbon Neutral Myth: Offset Indulgences for your Climate Sins” by Carbon Trade Watch (Smith 2007) includes case studies of the Carbon Neutral Company (formerly known as Future Forests) and of a few different offsetting projects. It also adds an analysis of how celebrity endorsements have helped to legitimize such projects.

The recent emergence of a voluntary carbon market with the potential to “offset” emissions is a relevant development within the larger context of climate change mitigation, but research has, so far, been lagging behind. Most research has focused on the ‘compliance’ or ‘regulatory’ market, where the demand is generated by legally mandated reductions. This part of the carbon market includes the Kyoto markets, the EU Emissions Trading Scheme, the US Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative and the Australian New South Wales Greenhouse Gas Abatement Scheme. It might therefore be indicative that at Point Carbon’s 2007 “Carbon Market Insight” conference in Copenhagen, the voluntary carbon market was for the first time included in the conference agenda with a well-attended roundtable on “Voluntary Carbon Offsets”.

As the voluntary carbon market is in an early stage of development, it is difficult to estimate its current size. The World Bank study “State and Trends of the Carbon Market” (Capoor and Ambrosi 2007) estimate the volumes and values to 65 million Verified Emissions Reductions for €246 million including trades on the Chicago Climate Exchange. It is difficult to make a good estimation since there are no comprehensive registries of the transactions made. Hence, estimations of future trends are more uncertain, but one might still want to note that the U.S. analyst Trexler imagines the U.S. market to double every year from, perhaps, 20MtCO2 in 2006 to 250 MtCO2 by 2011 (Trexler 2007).

While carbon credits produced by CDM/JI under the Kyoto Protocol are intergovernmentally regulated and supervised, and therefore include third-party verification and transparency in a structured process, the voluntary carbon market is not regulated, emissions reductions are not necessarily ‘certified’, the actors are not ‘accredited’, and there are many different verification standards competing for attention.Footnote 14 Many individuals and institutional actors in the carbon market are currently working on developing the ‘Voluntary Carbon Standard’ (VCS), which aims to set a basic quality threshold. The VCS is backed by The Climate Group, the International Emissions Trading Association (IETA) and the World Economic Forum Global Greenhouse Register and might therefore hold the potential for success. Capoor and Ambrosi (2007, 36) refer to the voluntary carbon market as a wide-open space in urgent need for standards, but it remains to be seen how those standards not only draw on existing CDM practices, but also accommodate the specific characteristics of the voluntary carbon market.

In addition to the voluntary carbon market as a baseline and credit system, private mitigation projects have also emerged within the corporate world. One remarkable trend is the emergence and consolidation of different voluntary CO2 emissions reduction programmes put forward by individual companies. For example, more than 100 U.S. corporations, among them leading companies such as Procter & Gamble, Coca-Cola, DuPont and Alcoa, have set or already achieved voluntary targets (Vogel 2005). Next to these firm-based initiatives, there are a number of network arrangements that incorporate a number of companies. Among others, Environmental Defense and the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) have both teamed up with corporations to set up voluntary targets for emissions reduction that are independently monitored. In addition, a number of individual companies have adopted and experimented with internal trading systems. The logic behind these actions could be described as follows: first and foremost, companies prepare for a political change in the U.S. that could lead to a more positive stance on binding emissions reduction. Second, companies have, although to different degrees, experienced considerable monetary implications of voluntary reduction programmes. Vogel (2005, 130) reports that Alcoa alone has reduced costs of about US $100 million annually through reduced energy use and related environmental performance improvements.

Furthermore, private actors in cooperation with municipalities, public universities and states have developed the first U.S.-based voluntary but legally binding emissions trading scheme, the Chicago Climate Exchange (CCX). Participating members have agreed to reduce their global greenhouse gas emissions 4% (1% per year) below an annual baseline emission average of the years 1998–2001. In the second commitment period from 2007 to 2010, reductions will be 6%. Members trade ‘carbon financial instruments’ (equal to 100 tons of carbon dioxide) that have been allocated according to their current emissions and the baseline scenario. Participants that exceed their emissions allowance can buy carbon financial instruments from those participants that are in excess of reductions. The programme-wide emissions baseline has dropped from 250,761,100 metric tons of CO2 in 2004 to 226,510,000 in 2005. However, a number of criticisms have been raised against the CCX. First, the annual emissions reduction of 1% is not very ambitious. Many companies are expected to reach this reduction with just some cosmetic changes to their operations. A second criticism is related to the market-based nature of a carbon-trading programme. The financial incentive to avoid an excess of the individual carbon allowance will increase with the market price for carbon financial instruments. With a market price of around US $3.30 in January 2007, the economic steering effect of the CCX is rather limited. Despite these shortcomings, carbon trading is getting more institutionalized globally. Next to the EU Emissions Trading Scheme, CCX has opened a European branch. In addition, recent attempts by the International Emissions Trading Association to standardize the verification of carbon reduction units (IETA 2006) underline the growing importance of private market-building approaches.

From our perspective, the voluntary carbon market is a site of climate governance beyond the state. The current search for common standards, registries and reporting procedures indicates a trend towards the institutionalization of climate governance beyond the international negotiation routine. The emerging norm of ‘carbon neutrality’ is currently expressed and contested not only on the carbon market, but also among the media, NGOs and local communities. Hence, carbon neutrality and the ensuing practices of carbon offsetting can be viewed as a policy instrument not just ‘beyond the state’, but within a transnational public sphere with the potential to mitigate climate change largely independent of state action.

3.2 Transnational climate governance through networks

Next to governing through markets, networks have emerged as a central steering mechanism in global environmental governance. This section provides a mapping of networks within the transnational arena of global climate governance, including public non-state networks such as the C40 global cities partnership, hybrid networks emanating from public–private sources of authority such as the WSSD partnerships, and finally networks whose authority derives from purely private sources, such as corporate social responsibility and standard-setting initiatives.

3.2.1 Public non-state networks in transnational climate governance: the case of global city partnerships

Next to public–private and private networks, the cooperation of public non-state actors gains relevance in global climate governance. Cities are a prime example of public authority that transcends the dichotomy of national/international (Bulkeley and Betsill 2003). Increasingly, cities have formed cooperative arrangements to exchange information, learn from best practices and consequently mitigate carbon dioxide emissions independently from national government decisions. These developments are interesting from both the agency and architecture perspective. In terms of agency, city networks illustrate that the drivers of climate policies can no longer be equated with governments and their diplomatic corps, but have diversified to include the local as a central level of climate governance. In terms of architecture, city networks for climate change mitigation add a crucial layer to the complexity of global climate governance, as their individual contributions to problem solving can no longer be subsumed under national commitments taken by states within the UNFCCC/Kyoto framework. We discuss these aspects briefly below.

A prime example of a public non-state network in global climate governance is the Cities for Climate Protection (CCP) programme organized by Local Governments for Sustainability (ICLEI), an international association of local governments and national and regional local government organizations that have made a commitment to sustainable development. ICLEI began working on the issue of global climate change in 1991, when it launched the Urban CO 2 Reduction Project, involving 14 municipalities in North America and Europe. This campaign, which ran until 1993, was designed to “develop comprehensive local strategies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and quantification methods to support such strategies” (ICLEI 1997, p. 5).

On the basis of the success of the Urban CO2 Reduction Project, ICLEI launched its CCP campaign in 1993 at the Municipal Leaders’ Summit on Climate Change and the Urban Environment held at the United Nations (cf. Betsill 2001, p. 395). Any municipal government is able to join Cities for Climate Protection by becoming a formal signatory to a National Municipal Leaders’ Declaration on Climate Change. In 2008, 692 communities in 31 countries are CCP members, with a clear bias towards Australia (196), the USA (159), and Canada (109). It is estimated that CCP members account for approximately 15% of global anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions.Footnote 15

The CCP programme has three main goals: quantifiable reductions in local greenhouse gas emissions, improvement of air quality, and the enhancement of urban livability and sustainability. In achieving these goals, the CCP programme is premised on the assumption that while the efforts of any single local government to reduce greenhouse gas emissions may be relatively modest, by working together local authorities can make a significant contribution to the efforts to mitigate climate change (Betsill 2004, p. 477). Participation in the CCP programme includes a number of defined steps. First, interested local governments begin participating in the CCP programme by passing a resolution pledging to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from their local government operations and throughout their communities. Each local government sets its own emission reduction target and develops a Local Action Plan outlining actions that the city will pursue to meet its target. After passing the resolution, the local government designates a staff member and an elected official to serve as the city’s liaison to ICLEI.

The approach through which the CCP’s goals are expected to be reached is the so-called 5 milestones approach to which members commit themselves in an attempt to control GHG emissions. It consists of the following elements: (1) conduct a baseline emissions inventory and forecast; (2) adopt an emissions reduction target for the forecast year; (3) develop a Local Action Plan through a multi-stakeholder process (most plans also incorporate public awareness and education efforts); (4) implement policies and measures (e.g. energy efficiency improvements to municipal buildings and water treatment facilities, streetlight retrofits, public transit improvements, installation of renewable power applications, and methane recovery from waste management); and finally (5) monitor and verify results. Tangible results of this approach are difficult to verify. ICLEI itself estimates that the U.S.-based CCP participants mitigate approximately 23 million tons of carbon dioxide annually (ICLEI 2006). Scholars have thus emphasized the ‘soft’ results of the CCP, such as increased access to relevant technical information and policy learning (Betsill 2004, p. 487).

A second example of a public non-state network in transnational climate governance is the C40 network. In August 2006, the Large Cities Climate Leadership Group, a coalition of then 18 global cities, was joined by the Clinton Climate Initiative to form the C40, a partnership of 40 major cities that have pledged to reduce carbon emissions and increase energy efficiency in large cities across the world. In the words of Nicholas Stern, economic advisor to the UK government: “The C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group is a tremendous idea and a fine example of the different dimensions of international collaboration” (C40 2008). Despite such praise, the C40 initiative is in such an early stage of its implementation that an evaluation of its performance and impacts is currently not feasible. Taken together, the CCP programme and the C40 initiative illustrate our claim that contemporary climate governance cannot adequately be analysed from a purely international perspective, but has to take into account the multiple spheres of authority emerging in global climate governance today.

3.2.2 Public–private networks in transnational climate governance: the case of WSSD partnerships for sustainable development

Public–private partnerships, that is networks of different societal actors, including governments, international agencies, corporations, research institutions and civil society organizations, have become a cornerstone of the current global environmental order, both in discursive and material terms. At the UN level, partnerships have been endorsed by the former Secretary General Kofi Anan through the establishment of the Global Compact, a voluntary partnership between corporations and the United Nations, as well as through the so-called type-2 agreement concluded by governments at the World Summit for Sustainable Development (WSSD) in Johannesburg in 2002 that institutionalizes public–private implementation partnerships in issues areas ranging from biodiversity to energy and has been criticized for effectively privatizing parts of the policy responses to global change.

These networks typically bring together actors from various sectors—governments, industry, activists, scientists or international organizations—and build on a voluntary agreement to achieve a specific sustainability goal, in other words govern a distinct issue area. They are defined as “specific commitments by various partners intended to contribute to and reinforce the implementation of the outcomes of intergovernmental negotiations of the WSSD (Programme of Action and the Political Declaration) and to help the further implementation of Agenda 21 and the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)” (Kara and Quarless 2002). The United Nations invited such partnerships to register with the secretariat of the Commission for Sustainable Development (CSD), a sub-committee of the UN Economic and Social Council. By March 2007, 323 multi-stakeholder initiatives have been listed in the CSD Partnerships Database.Footnote 16

Out of the 323 WSSD partnerships formally registered, 96 are within the primary categories of “energy for sustainable development”, “air pollution/atmosphere” and “climate change”.Footnote 17 What is missing so far is an encompassing assessment of the effectiveness of these novel mechanisms of governance with regard to the ultimate objective of the climate change convention as defined in UNFCCC Article 2 and other international documents.

For the purpose of this article, we focus on some less ambitious and more descriptive questions in regard to the 27 partnerships that focus on climate change as their primary thematic area. First, what is the geographical scope of climate change partnerships? Second, what is the average duration of partnerships in this issue area? And third, is the climate change area dominated by one specific type of partner? To answer these questions, we draw on data collected for the Global Sustainability Partnerships Database (cf. Biermann et al. 2007a, b; but see also Bäckstrand 2008).

With regard to the geographical scope of WSSD partnerships in the thematic area of climate change, the lack of local and national scope is noteworthy (see Table 2). As one might expect given the global nature of the climate problem, globally geared partnerships are very frequent, performing above average (63%) compared to the total partnership sample (50.8%). However, given the high importance of adaptation within the climate change issue area and the immediate relevance of sustainability at the local level, the total absence of local partnerships from the climate sample is surprising. In fact, it underlines the frequently raised criticism that WSSD partnerships reflect given interest structures and therefore seldom deliver additional benefits that have not already been realized in more traditional multilateral or bilateral implementation programmes.

A second interesting observation relates to the average duration of WSSD climate change partnerships. Given the long-term effects of climate change and the given inertia of the climate system, it seems at least plausible to assume that partnerships in the area of climate change will either be frequently open-ended or long term. In fact, our assessment of the available data shows that 37% of all climate change partnerships are open-ended, compared to 28.3% in the total sample. In addition, the average duration compares 6.1–4.9 years in favour of climate partnerships. We can tentatively conclude that climate change partnerships within the context of WSSD reflect the specific long-term nature of the climate problem in their duration. However, it is unclear whether the observed duration pattern is adequate in achieving the partnership goals and thereby contributing to, at least partially, solving the climate change problem.

Turning to the question of leadership within our climate change sample, three observations are noteworthy.Footnote 18 First, leadership by UN agencies is less frequent in the climate change sample than in the total (12.1% compared to 16.7%), while state leadership is above average at 33.3 compared to 24.4%. This finding is consistent with the argument that the politically sensitive area of climate change is less likely to be governed by international agencies but is expected to remain under the control of governments. As a second observation, business actors are slightly overrepresented in the climate change sample (6.1% compared to 2.6%), but are still less frequently found in leadership roles than standard arguments about business interests in climate change might suggest. One explanation could be that the advantages of participation in partnerships as a lead-partner do not outweigh the costs and therefore business actors remain either absent or participate in less prominent roles. However, as the participation rate for business is higher than in the total sample, a business case for climate change might well exist. This observation is in line with the growing relevance of specific business interests in climate change, such as insurance, investors and consultancy firms. Finally, research institutions are underrepresented in climate change partnerships (3% compared to 11.8%), which is surprising in so far as science plays a major role in defining the problem of climate change as well as in finding solutions.

In sum, our preliminary assessment of climate change partnerships within the sample of WSSD partnerships has pointed to a number of open questions, in particular with regard to the effectiveness of public–private approaches. For example: Does the average duration of climate change partnerships adequately reflect the nature of the climate system? Is effective implementation of climate-related activities possible without a major contribution by business actors (both in terms of making an actual impact and in terms of providing additional financial resources)? Or, how can we explain the lack of local-level partnerships in an issue area where, at least rhetorically, high emphasis is placed on delivering sustainable development to local communities?

3.2.3 Private networks in transnational climate governance: the case of corporate social responsibility

In addition to public–private networks that are still embedded within the larger multilateral arena, at least partially, there are a number of policies that are beyond the state in a more concrete sense, as their authority does not predominantly emanate from, or address public actors. Instead, they target transnational corporations and their global value and supply chains. Consequently, the majority of these approaches are discussed under the heading of corporate social responsibility (CSR), understood as “a concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and in their interactions with their stakeholders on a voluntary basis” (Commission of the European Communities 2001, p. 6).

Next to firm- or industry-level emissions reduction schemes and market-building approaches, a number of private networks have emerged that only indirectly aim at greenhouse gas emissions reduction, but rather focus on creating the necessary information and transparency for societal actors to assess corporate responses to climate change. Consequently, these benchmarking processes create a global competition among business actors to address climate change as a serious limitation to their profit-making activities. These emerging information-based governance schemes effectively institutionalize new norms at the transnational level, for example the norm to disclose corporate carbon emissions (in addition to the country-based reporting of the UNFCCC). We discuss the Carbon Disclosure Project as an illustrative example.Footnote 19

The Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) provides an institutional setting for the world’s largest collaboration of institutional investors on the business implications of climate change. CDP represents an efficient process whereby many institutional investors collectively sign a single global request for disclosure of information on greenhouse gas emissions. In 2007, 225 investment firms, representing over 31 trillion $US, are CDP supporters. In 2006, CDP has asked the FT 500 (the 500 largest firms by market capitalization) the fourth time in a row to disclose their carbon emissions and emissions reduction approaches along with information about climate change-related management strategies and participation in emissions trading (CDP 2006). After 47, 59, and 71% in the three preceding surveys, 72% have responded to CPD 4 in 2006. Interestingly, sectors that have a high impact on carbon emission, such as the electric utility sector, have performed above average in the FT 500 index as a whole, while, not surprisingly, US companies are lagging behind European companies (60% compared to 82%). In addition to the regular survey, more than 1,000 large corporations report on their emissions through the CDP’s website. Although it is too early to assess the effectiveness of the CDP and the wider carbon disclosure discourse, arguably institutional investors have acquired agency beyond the state in global climate governance by, at least partially, institutionalizing the norm of corporate disclosure of carbon emissions and carbon reductions.Footnote 20

In addition to the complexity of agency, the architecture of global climate governance is highly fragmented. Within the private realm of climate governance, a number of approaches exist that have no link to the international arena and therefore can hardly be integrated in or at least synchronized with the ongoing post-2012 negotiations. However, a number of interlinkages are also visible. Being the most obvious case, companies have related their firm- or industry-level emissions reduction programmes to the international targets and timetables approach of the Kyoto Protocol. Less obvious, but no less important, the business-NGO partnership The Climate, Community & Biodiversity Alliance (CCBA) has recently announced the first two forestry projects to be independently certified under its Climate, Community & Biodiversity (CCB) Standards.Footnote 21 The standard evaluates land-based carbon mitigation projects in forestry and thereby relates to the so-called land use, land use change and forestry section of the Kyoto Protocol.Footnote 22 On this account, private standardization attempts to fill critical gaps in the operationalization and implementation of international agreements.

In sum, the current developments in CSR clearly underscore the relevance of a broadened analytical perspective on global climate change governance. With an increasing number of non-state actors acquiring agency beyond the state and the deepening institutionalization of non-state approaches towards climate change such as market- and information-based mechanisms, a strictly international and state-centered perspective seems no longer viable. Instead, focusing on the transnational global climate governance arena shows the importance of CSR for effective climate politics.

4 Conclusions

In this article we have argued for a fresh perspective on current global climate governance. In particular, we believe a new conceptualization of global climate governance is essential in order to understand the increasing complexity, segmentation and functional differentiation of climate politics. Our notion of a transnational arena of climate governance offers such a concept and opens up space for remapping key sites of public, hybrid and private authority over the climate issue. Following a vibrant debate about the inadequacy of the public/private dichotomy in political theory and the recent trend towards a multi-actor and multi-level perspective in the discipline of IR, we suggest to position the emergent arena of transnational climate governance within a larger shift towards a global public domain.

In short, our article reflects two major purposes, one conceptual and one empirical. First, we aimed to develop a better conceptual vantage point to analyse the potential problem-solving contributions of different non-state actors and institutions (including a critical perspective on the normative implications of such a development). In light of a growing complexity of global climate policy, we believe that an expansion of our analytical toolkit is both necessary and rewarding. We argue that next to the international arena of global climate governance consisting of states and public agencies, there is an increasingly institutionalized arena of transnational global climate governance. What is missing to date is a detailed assessment of agency beyond the state in regard to the institutional arrangements different actors create and sustain in order to address the problem of climate change and the resulting overarching architecture of climate governance. Consequently, as our second purpose, we attempt to provide an up-to-date empirical account of the burgeoning field of transnational climate governance and a critical assessment of its problem-solving capacity.

With regard to the former objective, we have provided a broader perspective on global climate governance that takes into account public, hybrid and private sources of authority. We have provided an overview of central empirical developments in the field, with a focus on those that are still linked to the international arena (e.g. the partnerships that have emerged from the 2002 Johannesburg Summit) and those that operate in greater distance from the established field of international politics, such as the carbon neutrality approach.

In sum, our empirical analysis has highlighted some important aspects: first, transnational approaches towards global climate change governance might increase the transparency of the system, for example through initiatives like the Carbon Disclosure Project. Second, transnational approaches provide a clear signal to the political system of national governments and international organizations that climate change features high on the global agenda. Third, public–private partnerships, such as the WSSD partnerships and the CDM, have displayed rather mixed results. And finally, Carbon Neutrality emerges as novel discourse in global climate governance that potentially shifts the agency from public actors such as states to individuals.

Concluding from our empirical analysis, we want to bring forward some preliminary critical observations. First, the frequent interlinkages within the transnational arena (e.g. between CSR initiatives and carbon neutrality) and beyond (e.g. the link between carbon neutrality and the carbon market) make the overall system more complex. This offers more possibilities for issues-linkages and strategic bargains among actors (both governments and non-state actors), but at the same time increases the need for coordination among a growing number of agents in global climate governance. It remains to been seen how higher degrees of coordination can be achieved in the absence of a centralized structure of authority and before norms, rules and procedures are established and recognized by a large part of the relevant actors. As a result, we need to further our knowledge about the systemic interaction between the international and transnational global climate arena and the possibility for effective and equitable governance, taking into account a growing number of agents in a multiplicity of institutional contexts. Second, as there is currently neither an overall account of the mitigation commitments brought forward by a host of private actors nor a trustworthy verification system for those commitments, the effectiveness of transnational climate mitigation instruments remains to be assessed. However, we believe that our remapping exercise presented in this article can be a useful starting point for future research on the role and relevance of transnational approaches to the global climate crisis.

Notes

A 2006 poll in the US for example shows that nearly three out of every four individuals—74%—are more convinced today that global warming is a reality than they were two years before. See http://www.zogby.com/news/ReadNews.dbm?ID=1161.

By stressing the current trend towards transnationalization in global climate governance, we do not stipulate that transnationalization in general is a novel trend in world politics. We position the current debate within the long-standing scholarly discussion on transnational politics in Sect. 2.

We broadly define transnationalization as a deepening and broadening of interactions, processes, and institutions that cross national boundaries and include non-state actors. On this account, a change in policies, institutional arrangements and the underlying norms is regarded as transnationalization as long as it includes non-state actors and has a boundary-spanning dimension. This understanding is in line with recent scholarship on the transnationalization of environmental politics (Pattberg 2005, 2007).

This functional multiplication of actors extends to governments, where we can distinguish at least three different groups: industrialized countries that have ratified the Kyoto Protocol and committed to limit their greenhouse gas emissions by an average of 5% by 2012; industrialized countries that reject Kyoto, but intend to develop alternative regulatory approaches and architectures of international cooperation; and developing countries that support Kyoto in principle, and have ratified it, but do not need to limit or reduce their emissions within the first commitment period.

On the related concept of environmental regime conflicts, see Zelli (2005).

For a recent example see Breitmeier et al. (2006).

In contrast to the modes of governance, architecture and agency are analytical concepts to understand how the different steering modes are situated within the larger architecture of climate governance and how authority within that architecture is constructed.

For a further elaboration of the concept of agency beyond the state, see Biermann (2007).

We exclude the European Emissions Trading Scheme from our discussion, because it operates under a considerable shadow of hierarchy and therefore does not comply with our conceptualization of transnational climate governance.

MtCO2e stands for “million tones of carbon dioxide equivalent”. This is the standard measurement of the amount of CO2 emissions that are reduced or secluded from the environment.

For an excellent summary of the discursive practices around climate governance beyond the state, see Bäckstrand and Lövbrand (2006).

Appendix 3 in Bayon et al. (2007) offers a recent overview of the various standards.

For more information about CCP membership, see http://www.iclei.org/index.php?id=800, retrieved June 19, 2008.

See http://webapps01.un.org/dsd/partnerships/public/welcome.do, retrieved 5 October, 2007.

Note that these categories are based on the self-description of partnerships in the CSD partnership database.

Leadership refers to the question of who is formally (by registration with the CSD database) a lead-partner within a partnership. Note that multiple lead-partners per partnership are possible.

Another emerging non-state information-based governance scheme is the Investor Network on Climate Risk, organized by the non-profit organization ‘Coalition for Environmentally Responsible Economies’, an institutionalized cooperation of leading US environmental organizations, social responsible investors and companies.

For a general assessment of the influence of transnational CSR schemes, see Pattberg (2006).

Under Article 3.3 of the Kyoto Protocol, Parties decided that greenhouse gas removals and emissions through certain activities—namely, afforestation and reforestation since 1990—are accounted for in meeting the Kyoto Protocol’s emission targets.

References

Andonova, L., Betsill, M., & Bulkeley, H. (2007, May). Transnational climate change governance. Paper presented at the 2007 Amsterdam Conference on the Human Dimensions of Global Environmental Change, Amsterdam.

Arendt, H. (1958). The human condition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bachram, H. (2004). Climate fraud and carbon colonialism: The new trade in greenhouse gases. Capitalism, Nature, Socialism, 15, 5–20.

Bailey, J. (2000). Some meanings of ‘The Private’ in sociological thought. Sociology, 34(3), 381–401.

Bailey, J. (2002). From public to private: The development of the concept of the ‘Private’. Social Research, 69(91), 15–31.

Bayon, R., Hawn, A., & Hamilton, K. (2007). Voluntary carbon markets. London: Earthscan.

Bäckstrand, K. (2008). Accountability of networked climate governance: The rise of transnational climate partnerships. Global Environmental Politics, 8(3), 74–102.

Bäckstrand, K., & Lövbrand, E. (2006). Planting trees to mitigate climate change: Contested discourses of ecological modernization, green governmentality and civic environmentalism. Global Environmental Politics, 6(1), 50–75.

Beacroft, M. (2007). Defining political theory: An Arendtian approach to difference in the public realm. Politics, 27, 40–47.

Betsill, M. (2001). Mitigating climate change in US cities: Opportunities and obstacles. Local Environment, 6(4), 393–406.

Betsill, M. (2004). Transnational networks and global environmental governance: The cities for climate protection program. International Studies Quarterly, 48(2), 471–493.

Biermann, F. (2007). ‘Earth System Governance’ as a crosscutting theme of global change research. Global Environmental Change, 17(3–4), 326–337.

Biermann, F., Chan, S., Mert A., & Pattberg, P. (2007a). Multi-stakeholder partnerships for sustainable development: Does the promise hold? In P. Glasbergen, F. Biermann & A. P. J. Mol (Eds.), Partnerships, governance and sustainable development. Reflections on theory and practice (pp. 239–260). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Biermann, F., & Pattberg, P. (2008). Global environmental governance: Taking stock, moving forward. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 33, 277–294.

Biermann, F., Pattberg, P., Chan, M., & Mert, A. (2007b). Partnerships for sustainable development: An appraisal framework. Global Governance Working Paper No 31. Amsterdam: The Global Governance Project.

Biermann, F., Pattberg, P., van Asselt, H., & Zelli, F. (2007c). Fragmentation of global governance architectures—the case of climate policy. Global Governance Working Paper No 34. Amsterdam: The Global Governance Project.

Börzel, T. A., & Risse, T. (2005). Public-private partnerships: Effective and legitimate tools of international governance. In E. Grande & L. W. Pauly (Eds.), Reconstituting political authority: Complex sovereignty and the foundations of global governance (pp. 195–216). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Boyd, E., Gutierrez, M., & Chang, M. (2007). Small-scale forest carbon projects: Adapting CDM to low-income communities. Global Environmental Change, 17, 250–259.

Brainard, C. (2007). Emissions Markets: The Good, The Bad, The Ugly. Columbia Journalism Review. Retrieved October 20, 2008, from http://www.cjr.org/behind_the_news/emissions_markets_the_good_the.php.

Breitmeier, H., Young, O., & Zürn, M. (2006). Analyzing international regimes. From case study to database. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Bulkeley, H., & Betsill, M. (2003). Cities and climate change. Urban sustainability and global environmental governance. London: Routledge.

C40 (2008). C40 Large Cities Climate Summit. C40, London. Retrieved June 15, 2008, from http://www.c40cities.org/summit/.

Capoor, K., & Ambrosi, P. (2007). State and trends of the carbon market 2007. Washington, DC: World Bank Institute.

Capoor, K., & Ambrosi, P. (2008). State and trends of the carbon market 2008. Washington, DC: World Bank Institute.

Carbon Disclosure Project. (2006). Carbon Disclosure Project Report 2006. Global FT500. CDP, London. Retrieved September 10, 2007, from http://www.cdproject.net/.

Commission of the European Communities. (2001). Promoting a european framework for corporate social responsibility. Brussels: Commission of the European Communities.

Conca, K. (2006). Contentious transnational politics and global institution building. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Cosbey, A., Murphy, D., Drexhage, J., & Balint, J. (2006). Making development work in the CDM: Phase II of the development dividend project. Winnipeg, Manitoba: International Institute for Sustainable Development.

Cutler, A. C., Haufler, V., & Porter, T. (Eds.). (1999). Private authority and international affairs. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Dingwerth, K. (2005). The democratic legitimacy of public-private rule making: What can we learn from the World Commission on Dams. Global Governance. A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations, 11(1), 65–83.

Dingwerth, K. (2007). The new transnationalism. Transnational governance and democratic accountability. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ellis, J., Winkler, H., Corfee-Morlot, J., & Gagnon-Lebrun, F. (2007). CDM: Taking stock and looking forward. Energy Policy, 35, 15–28.

Ferguson, Y. H., & Mansbach, R. W. (1996). Polities: Authority, identities and change. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press.

Ferguson, Y. H., & Mansbach, R. W. (2004). Remapping global politics: History’s revenge and future shock. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Haites, E., & Yamin, F. (2000). The clean development mechanism: Proposals for its operation and governance. Global Environmental Change, 10(1), 27–45.

Hall, R. B., & Biersteker, T. J. (Eds.). (2002a). The emergence of private authority in global governance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hall, R. B., & Biersteker, T. J. (2002b). The emergence of private authority in the international system. In R. B. Hall & T. J. Biersteker (Eds.), The emergence of private authority in global governance (pp. 3–22). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hamwey, R. M. (1998). A sustainable framework for joint implementation (of internal cooperation on climate change). International Environmental Affairs, 10, 79–97.

Harvey, F., & Fidler, S. (2007). Industry caught in carbon ‘smokescreen’. Financial Times, April 25.

ICLEI. (1997). Local government implementation of climate protection: Report to the United Nations. Toronto: ICLEI.

ICLEI. (2006). Combating climate change: A comprehensive look at local climate protection programs. Toronto: ICLEI. Retrieved June 20, 2008, from http://www.iclei-usa.org/action-center/learn-from-others/(resource)Case_Studies_Dec–2006.pdf.

International Emissions Trading Association (IETA). (2006). Voluntary carbon standard. Verification protocol and criteria. Geneva: IETA.

IPCC. (2007). Summary for policymakers. In S. Solomon, D. Qin, M. Manning, Z. Chen, M. Marquis, K. B. Averyt, M. Tignor & H. L. Miller (Eds.), Climate change 2007: The physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the fourth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jagers, S. C., & Stripple, J. (2003). Climate governance beyond the state. Global governance. A review of multilateralism and international organizations, 9(3), 385–399.

Kara, J., & Quarless, D. (2002, May). Guiding principles for partnerships for sustainable development (‘type 2 outcomes’) to be elaborated by interested parties in the context of the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD). Paper presented at the Fourth Summit Preparatory Committee (PREPCOM 4), Bali, Indonesia.

Keohane, R. O. (1984). After hegemony. Cooperation and discord in the world political economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Keohane, R. O., & Nye, J. S. (Eds.). (1972). Transnational relations and world politics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Keohane, R. O., & Nye, J. S. (1977). Power and interdependence. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company.

Lohmann, L. (2006). Carbon trading: A critical conversation on climate change, privatization and power. Development Dialogue, 48.

Meyer, A. (1995). Economics of climate change. Nature, 378, 433–433.

Mayntz, R. (2004). Governance theory als fortentwickelte Steuerungstheorie?. Köln: Max-Planck-Institute for the Study of Societies.

Miles, E. L., Underdal, A., Andresen, S., Wettestad, J., Skjaerseth, J. B., & Carlin, E. M. (Eds.). (2001). Environmental regime effectiveness. Confronting theory with evidence. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Monbiot, G. (2006). Paying for our sins. Guardian, October 18.

Okereke, C., & Bulkeley, H. (2007). Conceptualizing climate change governance beyond the international regime. Tyndall Centre Working Paper. Norwich: University of East Anglia.

Olsen, K. H. (2007). The clean development mechanism’s contribution to sustainable development: A review of the literature. Climatic Change, 84, 59–73.

Paterson, M., & Stripple, J. (2007). Singing climate politics into existence: On the territorialisation of climate change policymaking. In M. Pettenger (Ed.), The social construction of climate change: Power, knowledge, norms, discourses (pp. 149–172). London: Ashgate.

Pattberg, P. (2005). The institutionalization of private governance: How business and non-profit organizations agree on transnational rules. Governance: An International Journal of Policy, Administration, and Institutions, 18(4), 589–610.

Pattberg, P. (2006). The influence of global business regulation: Beyond good corporate conduct. Business and Society Review, 111(3), 241–268.

Pattberg, P. (2007). Private institutions and global governance. The new politics of environmental sustainability. Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Pearson, B. (2007). Market failure: Why the clean development mechanism won’t promote clean development. Journal of Cleaner Production, 15, 247–252.

Point Carbon. (2007). Carbon 2007—A new climate for carbon trading. London: Point Carbon.

Revkin, A. C. (2007). Carbon-neutral is hip but is it green? The New York Times, April 2007.

Robbins, T. (2006). The great green rip-off? The Observer Sunday, December 10.

Rosenau, J. N. (1997). Along the domestic-foreign frontier: Exploring governance in a turbulent world. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rowlands, I. H. (2001). The Kyoto Protocol’s ‘Clean Development Mechanism’: A sustainability assessment. Third World Quarterly, 22, 795–811.

Ruggie, J. G. (2004). Reconstructing the global public domain—issues, actors, and practices. European Journal of International Relations, 10(4), 499–531.

Smith, K. (2007). The Carbon Neutral Myth. Offset Indulgencies for your Climate Sins, Carbon Trade Watch. Retrieved September 10, 2007, from http://www.carbontradewatch.org/pubs/carbon_neutral_myth.pdf.

Schneider, L. (2007). Crediting the displacement of non-renewable biomass under the CDM. Berlin: Institute for Applied Ecology.

Stern, N. H. (2007). The economics of climate change: The stern review: Stern review on the economics of climate change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Trexler, M. (2007). US demand? Paper presented at the Point Carbon Carbon Market Insights 2007, Copenhagen.

UNEP. (2008). UNEP Risoe CDM/JI pipeline analysis and database. Retrieved June 11, 2008, from http://cdmpipeline.org/.

Van Asselt, H. (2007). From UN-ity to Diversity? The UNFCCC, the Asia-Pacific partnership, and the future of international law on climate change. Carbon and Climate Law Review, 1(1), 17–28.

Victor, D. G., Raustiala, K., & Skolnikoff, E. B. (1998). The implementation and effectiveness of international environmental commitments: Theory and practice. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Vogel, D. (2005). The market for virtue. The potential and limits of corporate social responsibility. Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Wara, M. (2007). Is the global carbon market working? Nature, 445, 595–596.

Zelli, F. (2005). The regime environment of environmental regimes. Conceptualizing international regime conflicts on environmental issues. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Studies Association, Honolulu, Hawaii. Retrieved September 10, 2007, from http://www.allacademic.com/meta/p69616_index.html.

Acknowledgements

The research reported in this article was conducted under the project ‘Adaptation and Mitigation Strategies: Supporting European Climate Policy (ADAM)’, financed by DG Research of the European Commission under the Sixth Framework Programme 2002–2006, Priority 1.1.6.3, Global Change and Ecosystems. The authors would like to thank Ans Kolk, David Levy, and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions