Abstract

While many papers have focused on socially unequal admissions in higher education, this paper looks at the persistence of class differentials after enrolment. I examine the social class gap in bachelor’s programme dropout and in the transition from bachelor’s to master’s in Denmark from the formal introduction of the bachelor’s degree in 1993 up to recent cohorts. Using administrative data, I find that the class gap in bachelor’s departures has remained constant from 1993 to 2006, with disadvantaged students being around 15 percentage points more likely to leave a bachelor’s programme than advantaged students, even after adjusting for other factors such as grades from upper secondary school. Importantly, the class gap reappears at the master’s level, with privileged students being more likely to pursue a master’s degree than less privileged students. The size of the class gap is remarkable, given that this gap is found among a selected group of university enrolees. As other studies have found that educational expansion in higher education is not necessarily a remedy for narrowing the class gap in educational attainment, scholars need to pay more attention to keeping disadvantaged students from leaving higher education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

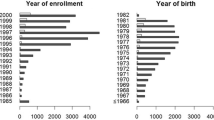

I use the newest data available, but do not include cohorts enrolled later than 2006, to be able to follow students well after their enrolment year.

As robustness checks, I also ran models of dropout status at years 6 and 10 after bachelor enrolment; these models produced the same results as those presented in this paper.

I choose to model dropout by linear probability models over event history models, because (1) my primary aim is simply to gauge the social gap in non-completion and not the timing of events (i.e. when dropout occurs), and (2) administrative data measure the exact occurrence of dropout poorly (as students may be registered as enrolled long after they have dropped out).

Average predicted probabilities from logit models yield virtually identical results as the ones presented here.

Not shown in Table 1, most of those enrolled in bachelor’s programmes have attended the general Gymnasium (73%), with a smaller share having chosen the technical/business-oriented track (13%) and a different type of the general Gymnasium (‘HF’, 12%) catered towards mature students (on average 23 years old when they obtain their diploma). These students are generally from lower educated homes than students from the general Gymnasium. HF students are on average 20% more likely to dropout than STX students are, even though their GPA is fairly similar (7.9 and 8.1, respectively).

This assumption is supported by the fact that the University of Roskilde is the institution with the highest share of bachelor’s degree holders leaving their institution to pursue their master’s degree elsewhere.

Although we cannot deduce that leavers would have enjoyed the same income as stayers, had they finished their degree, the income gap is unlikely to be attributable solely to selection; that is, dropouts would have some unobservable traits leading them to have lower economic returns, regardless of whether or not they obtained a degree.

Disadvantaged students with a GPA in the top decile have a very high dropout rate, suggesting that this small group will be heavily selected on unobservable traits, which may lead them, for example, to venture successfully into the labour market without a degree. It could also be the case that top performing disadvantaged students enrol in highly selective programmes where they are most likely to feel culturally out of place and hence dropout more (I thank an anonymous reviewer for this excellent point).

This pattern holds true even if we distinguish between different tracks in the higher education-preparatory upper secondary school (general, business, technical and higher preparatory track).

References

Allensworth, E. M., & Clark, K. (2020). High school GPAs and ACT scores as predictors of college completion: Examining assumptions about consistency across high schools. Educational Researcher, 49(3), 198–211.

Archer, L., & Hutchings, M. (2000). “Bettering yourself”? Discourses of risk, cost and benefit in ethnically diverse, young working-class non-participants’ constructions of higher education. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 21(4), 555–574.

Argentin, G., & Triventi, M. (2011). Social inequality in higher education and labour market in a period of institutional reforms: Italy, 1992-2007. Higher Education, 61, 309–323.

Bar Haim, E., & Shavit, Y. (2013). Expansion and inequality of educational opportunity: A comparative study. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 31, 22–31.

Bernardi, F. (2014). Compensatory advantage as a mechanism of educational inequality. Sociology of Education, 87(2), 74–88.

Bernstein, B. (1990). Class, codes and control: Vol. 4. The structuring of pedagogic discourse. Routledge.

Boudon, R. (1974). Education, opportunity and social inequality. Changing prospects in Western society. John Wiley & Sons.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). Distinction. A social critique of the judgement of taste. Routledge.

Bourdieu, P. (1996). The state nobility: Elite schools in the field of power. Polity Press.

Bourdieu, P., Passeron, J.-C., & Martin, M. d. S. (1994). Academic discourse: Linguistic misunderstanding and professorial power. Stanford University Press.

Breen, R., & Goldthorpe, J. H. (1997). Explaining educational differentials. Rationality and Society, 9(3), 275–305.

Breen, R., & Jonsson, J. O. (2005). Inequality of opportunity in comparative perspective: Recent research on educational attainment and social mobility. Annual Review of Sociology, 31, 223–243.

Christie, H., Tett, L., Cree, V. E., Hounsell, J., & McCune, V. (2008). “A real rollercoaster of confidence and emotions”: Learning to be a university student. Studies in Higher Education, 33(5), 567–581.

Contini, D., Cugnata, F., & Scagni, A. (2018). Social selection in higher education. Enrolment, dropout and timely degree attainment in Italy. Higher Education, 75, 785–808.

Doren, C., & Grodsky, E. (2016). What skills can buy: Transmission of advantage through cognitive and noncognitive skills. Sociology of Education, 89(4), 321–342.

Goldrick-Rab, S. (2006). Following their every move: An investigation of social-class differences in college pathways. Sociology of Education, 79(1), 61–79.

Goldrick-Rab, S., & Pfeffer, F. T. (2009). Beyond access: Explaining socioeconomic differences in college transfer. Sociology of Education, 82(2), 101–125.

Goldthorpe, J. H. (1996). Class analysis and the reorientation of class theory: The case of persisting differentials in educational attainment. British Journal of Sociology, 47(3), 481–505.

Grodsky, E., & Riegle-Crumb, C. (2010). Those who choose and those who don’t: Social background and college orientation. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 627(1), 14–35.

Haveman, R., & Wilson, K. (2007). Access, matriculation, and graduation. In S. Dickert-Conlin & R. Rubenstein (Eds.), Economic inequality and higher education (pp. 17–43) Russell Sage Foundation.

Herbaut, E. (2020). Overcoming failure in higher education: Social inequalities and compensatory advantage in dropout patterns. Acta Sociologica, online first: June 2.

Holm, A., & Jæger, M. M. (2011). Dealing with selection bias in educational transition models: The bivariate probit selection model. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 29(3), 311–322.

Hovdhaugen, E. (2009). Transfer and dropout: Different forms of student departure in Norway. Studies in Higher Education, 34(1), 1–17.

Jæger, M. M., & Holm, A. (2007). Does parents’ economic, cultural, and social capital explain the social class effect on educational attainment in the Scandinavian mobility regime? Social Science Research, 36(2), 719–744.

Johnes, G., & Mcnabb, R. (2004). Never give up on the good times: Student attrition in the UK. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 66(1), 23–47.

Karlson, K. B. (2019). College as equalizer? Testing the selectivity hypothesis. Social Science Research, 80, 216–229.

Larsen, M. S., Kornbeck, K. P., Kristensen, R., Larsen, M. R., & Sommersel, H. B. (2013). Dropout phenomena at universities: What is dropout? Why does dropout occur? What can be done by the universities to prevent or reduce it? Danish Clearinghouse for Educational Research.

Mare, R. D. (1981). Change and stability in educational stratification. American Sociological Review, 46(1), 72–87.

Mare, R. D. (1993). Educational stratification on observed and unobserved components of family background. In Y. Shavit & H.-P. Blossfeld (Eds.), Persistent inequality: Changing educational attainment in thirteen countries (pp. 351–376). Westview Press.

Mood, C. (2009). Logistic regression: Why we cannot do what we think we can do, and what we can do about it. European Sociological Review, 26(1), 67–82.

Narayan, A., Van der Weide, R., Cojocaru, A., Lakner, C., Redaelli, S., Gerszon Mahler, D., Ramasubbaiah, R. G. N., & Thewissen, S. (2018). Fair progress?: Economic mobility across generations around the world. World Bank Group.

OECD. (2018). A broken social elevator? How to promote social mobility. OECD Publishing.

Reay, D. (2003). A risky business? Mature working-class women students and access to higher education. Gender and Education, 15(3), 301–317.

Reay, D., David, M., & Ball, S. (2001). Making a difference?: Institutional habituses and higher education choice. Sociological Research Online, 5(4), 14–25.

Reay, D., Crozier, G., & Clayton, J. (2009). “Strangers in paradise”? Working-class students in elite universities. Sociology-the Journal of the British Sociological Association, 43(6), 1103–1121.

Shavit, Y., Arum, R., & Gamoran, A. (2007). Stratification in higher education. A comparative study. Stanford University Press.

Stuber, J. M. (2011). Inside the college gates: How class and culture matter in higher education. Lexington Books.

Thomsen, J. P. (2012). Exploring the heterogeneity of class in higher education. Social and cultural differentiation in Danish university programmes. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 33(4), 565–585.

Thomsen, J.-P. (2015). Maintaining inequality effectively? Access to higher education programmes in a universalist welfare state in periods of educational expansion 1984-2010. European Sociological Review, 31(6), 683–696.

Thomsen, J.-P., Hedman, J., Helland, H., Bertilsson, E., & Dalberg, T. (2017). Higher education participation in the Nordic countries 1985-2010—a comparative perspective. European Sociological Review, 33(1), 98–111.

Troelsen, R., & Laursen, P. F. (2014). Is drop-out from university dependent on national culture and policy? The case of Denmark. European Journal of Education, 49(4), 484–496.

Ulriksen, L. (2009). The implied student. Studies in Higher Education, 34(5), 517–532.

Vignoles, A. F., & Powdthavee, N. (2009). The socioeconomic gap in university dropouts. B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 9(1), 1–36.

Wilbur, T. G., & Roscigno, V. J. (2016). First-generation disadvantage and college enrollment/completion. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 2, 1–11.

Winterton, M. T., & Irwin, S. (2012). Teenage expectations of going to university: The ebb and flow of influences from 14 to 18. Journal of Youth Studies, 15(7), 858–874.

Zarifa, D., Kim, J., Seward, B., & Walters, D. (2018). What’s taking you so long? Examining the effects of social class on completing a bachelor’s degree in four years. Sociology of Education, 91(4), 290–322.

Zhou, X. (2019). Equalization or selection? Reassessing the “meritocratic power” of a college degree in intergenerational income mobility. American Sociological Review, 84(3), 459–485.

Availability of data and material

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available, as only researchers employed at Danish authorized research institutions, for reasons of security, can get access to administrative data at Statistics Denmark.

Code availability

Data was analysed in Stata and coding files are available upon request from the author.

Funding

This research was supported by the Danish Council for Independent Research, grant no: 4180-00054A.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 64 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thomsen, JP. The social class gap in bachelor’s and master’s completion: university dropout in times of educational expansion. High Educ 83, 1021–1038 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00726-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00726-3