Abstract

Global university rankings currently attract considerable attention, and it is often assumed that such rankings may cause universities to prioritize activities and outcomes that will have a positive effect in their ranking position. A possible consequence of this could be the spread of a particular model of an “ideal” university. This article tests this assumption through an analysis of a sample of research-intensive universities in the Nordic region. Through document analysis and interviews with institutional leaders and staff from central administration, the study explores whether high-ranked Nordic universities take strategic measures as a response to global rankings, and whether the traditional identities of the universities are changing, as they are influenced and affected by the rankings. The study shows that rankings have a relatively modest impact on decision-making and strategic actions in the Nordic universities studied, and that there are few signs of rankings challenging the existing identities of the universities in this region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

University rankings are currently a worldwide phenomenon, attracting a lot of interest in higher education. For universities, rankings pose new challenges as certain dimensions of a university’s activities and performance is being exposed to a broader public (Dill and Soo 2005; Hazelkorn 2011). Based on the increasing globalization of the sector, and increased competition among universities, notions of excellence are frequently associated with the idea of being a world-class university (Salmi 2009; Hazelkorn 2013). While the discourse related to “world class institutions” is certainly not a new phenomenon, it has increased in importance both in terms of political ambitions nationally and as a strategic aim for the institutions (Deem et al. 2008). As a consequence of this, a number of countries have launched initiatives with the explicit goal of creating excellent and world-class universities (Hazelkorn 2013). Perhaps paradoxically, the oversimplified and proxy-based view of quality which is one of the bases for the appeal of university rankings is also one of the main criticisms (Hazelkorn 2013; Marginson 2014). Rankings provide a visualized image of where particular institutions are placed in the global hierarchy of higher education institutions. This information is also available for use by those with no knowledge about the complexity of the sector. Through this, rankings have captured the public attention worldwide, even if they have been the subject of much criticism both in terms of their conceptual and technical basis (Harvey 2008). Nevertheless, the common argument is that “rankings are here to stay”, and that rankings matter.

Hence, rankings can be seen as being highly intertwined with processes of globalization and they are also accused of promoting a particular kind of university—the world-class university (Salmi 2009). At the same time, one could question whether processes of globalization are spreading at an even pace and with similar scope in different parts of the world, and whether globalization—almost as a default—always leads to standardization. This article explores this assumption by studying how a group of Nordic research-intensive universities respond and react to global rankings. The key questions investigated here are (1) whether we can see that key values, norms and ideals related to the identity of Nordic research universities are being affected by the global rankings, and (2) whether the universities studied initiate special measures or actions intended to improve their position or status in the global rankings.

The Nordic region is a particularly interesting case for testing issues related to globalization as it can be argued that the global excellence agenda has entered the public debate in the Nordic countries, although this region is traditionally also known for the strong emphasis it places on values such as broad access to higher education, equality of opportunity and the fostering of democratic values, seemingly a parallel track to the global race for excellence. Hence, the Nordic region can be said to have quite ambiguous characteristics with respect to globalization. The Nordic region is a technologically advanced and a highly industrialized area where the countries making up the region have open economies and a highly skilled and educated population, not least due to a relatively well-developed and funded higher education sector. In this way, the Nordic region is open for, and indeed is a part of, a more globalized economy. At the same time, the Nordic region is also well known for having developed sophisticated welfare states in which protecting the population against some of the downsides of market competition has been a central aim. Through such aims, one could also argue that Nordic higher education could be a sector with some in-built potential to resist global pressures for change.

University rankings as identity signifiers

It is possible to argue that rankings can both challenge and consolidate the identity of research-intensive universities (Kehm and Stensaker 2009). For those universities that are not pleased with their positioning in the global rankings, rankings may imply that changes that can boost their profile and performance in certain areas have to be made (Hazelkorn 2011). For those universities at or near the top of the rankings, possible actions are perhaps more related to consolidating their current position and strengthening what is perceived as being their comparative advantage towards other universities (Dill and Soo 2005). Hence, rankings are not value free and rankings can also have an impact on university identity—the collective signification of “who we are” and “who we should be” as an institution.

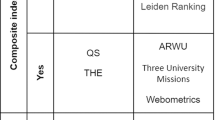

Arguing that rankings are not value free implies that rankings tend to emphasize some aspects of the activities and performance of universities at the expense of others (Dill and Soo 2005). A recent study has shown that age of institution and size of institution may influence ranking position (Piro et al 2014). The global rankings focused upon in the current article are ARWU (Shanghai) and Times Higher Education, as these are also considered highly prestigious.Footnote 1 In general, the Shanghai ranking is known to favour comprehensive research universities in English-speaking countries that have a wide coverage of disciplines (and strength in the natural sciences) with relatively few employees in educational positions (Liu and Cheng 2005; Marginson and van der Wende 2007). The focus is clearly on research, and purposefully so by the designers of the ranking as this was arguably the only indicator by which meaningful comparisons could be made across national borders (Liu and Cheng 2005). The Times Higher Education (THE) ranking has much more focus on internationalization and reputation indicators that are based on a global survey of university staff (Marginson and van der Wende 2007). Hence, it can be argued that two elements stand out as central for the rankings in focus here: research performance and reputation. This means that when we discuss how Nordic universities respond or react to global rankings, it is measures taken in these two areas that we have particularly focussed on.

University rankings—perspectives on their impact on university identity

Governance reforms in higher education in recent decades have led to increased focus on autonomy, accompanied by emphasis on management and reporting structures to cater for the increased pressure for accountability (Christensen 2011). In this perspective, global rankings represent a new global standard for university performance and reputation, and represent a source of information for management decisions on how to improve (Kehm and Stensaker 2009). These measures are also key ingredients in the concept of the so-called world-class university which in the last decade have been presented as the global university ideal which is constructed as a result of global rankings (Salmi 2009). Hence, in this perspective, university identities are externally given as particular images universities are forced to adapt to (Gioia et al 2000). This perspective is backed by the work of Ellen Hazelkorn who examined the use of rankings in university management and decision-making in several countries, arguing that rankings have had a profound effect on universities (Hazelkorn 2011; 2013). Her survey showed that 76 % of the institutional leaders reported that they used rankings to follow how other national institutions were doing, and 50 % reported that they followed global results. Furthermore, 40 % of the university leaders used rankings when they evaluated cooperation agreements (Hazelkorn 2013:4). Other studies have also backed the argument for adaptive and responsive universities. For example, studies focusing on developments within the UK have demonstrated how national rankings led to institutions actively trying to improve their position (Harvey 2008; Yorke 1997).

However, although globalization is undoubtedly affecting universities, one could still question the rapidness and comprehensiveness of the changes taking place in various countries and within institutions (Saarinen and Välimaa 2012). Hence, whether universities are willing and able to adopt identities created by international rankings could still be questioned. Universities are known to be organizations infused with values and norms that they develop over time and from the bottom-up (Clark 1983). In addition, they are also seen as fragmented organizations where disciplines create distinct academic cultures (Becher and Trowler 2001; Välimaa 1998), making the adaptation of external ideas challenging. Furthermore, universities engage in a variety of activities beyond those emphasized by rankings, and universities are known to balance competing and sometimes contradictory functions (Castells 2001). Hence, while universities indeed may have organizational identity(ies), one may doubt the extent to which such an identity is easily adaptable (Stensaker 2015). For example, development of organizational sagas that create a sense of unity and commitment through particular imagery and myths may take a very long time to develop (Clark 1972), at least in the time frame in which international rankings operate. Thus, in this perspective university identities are more internally developed and based on the historical legacies of universities which potentially could be quite resistant to external influence—even from global rankings (Selznick 1957; Albert and Whetten 1985).

It is also possible to outline a third perspective, combining insights from the first two. In this perspective, university identity is seen as something that is constructed between the environment and the individual organization—through dialogue, negotiations and interest articulation (Glynn 2008). This perspective is based on the insight that while identity is linked to uniqueness, identity is actually also about belonging to a certain group or entity (Pedersen and Dobbin 2006). For example, while it can be considered an advantage for a university to have a unique profile, that profile cannot be so unique that the organization no longer qualifies to be labelled as a “university”. In the latter case, the uniqueness would take away the legitimacy that follows being labelled as belonging to a recognized cluster of organizations (Pedersen and Dobbin 2006). This opens a more selective, but also a more path-dependent adaptation to global rankings. The existing identity shapes choices regarding the organizations which are chosen for comparison, resulting in possible clustering of universities with perceived similar identities. Research has shown that universities tend not only to focus on structurally similar organizations, but also their identity by focusing on reputation and organizational image (Labianca et al. 2001). However, the need to find a match between external pressures and internal legitimacy and history also implies that identity constrains available choice options (Glynn 2008).

While all three perspectives focus on university identities as the heuristic tool, they also indirectly deal with issues of convergence and diversity, although from very different perspectives. However, central to them all is the idea of that identity is created through comparison. In the first perspective, comparisons are made in relation to a global university ideal. In the second perspective, the comparison is historical and related to the inherent characteristics of the university. In the third perspective, the comparison is selective—only certain elements are seen as important. Of course, these comparisons are also related to the current position and how the university views its opportunities to improve its position. As such, if the universities see rankings as a relevant instrument, this can also create isomorphic pressures within the organization that are mediated by organizational identities. These pressures can take the form of certain measures to improve ranking performance. If this happens, the question that follows is the extent to which these new initiatives are strong enough to challenge simultaneously existing organizational identities.

Empirical design and methodology

The empirical setting

The responses to global reform trends and scripts take various forms at the national level. The national level can transfer directly, translate or develop buffering mechanisms as responses to these global trends (Gornitzka 2013). As such, national regulative and financial frameworks, incentives and governance models have to be taken into account when examining the role of rankings for institutional priorities (Harvey 2008). While institutions might compete in the global landscape, institutions are also clearly embedded in a national context with national mandates. Common in the Nordic countries is that their higher education systems can be considered to be quite similar, founded on a strong welfare state and universal access to higher education. However, ideas on excellence have become more prominent over time, and the Nordic countries follow different types of excellence initiatives. The Nordic countries are often described as being part of a single “Nordic model”, although research suggests that recent higher education reforms have indicated rather different national trajectories and combinations (Gornitzka and Maassen 2011), which may lead to the Nordic countries becoming more different from each other. Hence, the Nordic sphere can provide a quite good setting for studying how universities that are ranked operate in an environment of increased focus on excellence and strategic behaviour.

Up until now most of the existing research on rankings has focused primarily on countries with high levels of market focus and high levels of differentiation within the system, or on institutions that are near the top of the ranking lists. Based on this research, claims are made about the impact of rankings worldwide. However, fewer studies have looked at institutions that are doing quite well, but which are not at the very top of the league and there are also few studies of the impact of rankings in higher education systems that are less competitive. Hence, a study of the Nordic region provides a contrast to existing studies on the role of rankings, both with regard to ranking status and to the status of rankings in the higher education system.

Case selection

This study is based on a broad study of 14 universities in four Nordic countries. As the study was placed in the Norwegian context, the institutions that have been included are those that perform as well as or better than the four Norwegian institutions in the two main global rankings (ARWU and THE). While none of the universities are among the top 25, on a global scale these can be seen as comparatively well-performing universities (see Table 1). The positioning of the institutions includes some national differences. Norway and Finland have only one institution among the top 100 universities in the rankings, while Denmark has two and Sweden has three such institutions.

Common to all universities on the list is that they are quite old institutions, most of them over 100 years old and some much older. However, there is some diversity within the sample. Some are comprehensive research universities, NTNU, KTH and DTU, which are technical universities, and KI is a medical university. The universities also differ in size, although most universities are quite large. Hence, in order to make it to the ranking lists an institution has to be a large comprehensive university or a specialty school with strong focus on research (Kehm and Stensaker 2009).

Empirical data

For the 14 case institutions, the analyses are based on interviews with senior leadership and document analysis of strategic plans, in addition to an examination of university profiles on the institution websites. In the strategic plans, the following thematic areas have been examined: (a) how institutions collect and document results and (b) internationalization, and (c) the type and level of ambition the university has in terms of its national and international positioning, how this is operationalized and the kind of measures that have been introduced. Furthermore, we also examined whether and in what context rankings are mentioned. While strategic plans usually only represent a broad perspective of the institution, the documents can arguably also be seen to have a more symbolic value. At the same time, strategic plans also represent a direct representation of identity “who we are as an institution” and also signalling future ambitions of what the institution wants to achieve.

The interviews were conducted with key persons in the universities. In some cases, we were re-directed by senior leadership to talk to those working directly with rankings at these institutions. In addition to persons working specifically on rankings at a few of the case institutions, our respondents primarily included current and former rectors and research directors of these universities. The interviews were conducted as semi-structured exploratory expert interviews (Bogner and Menz 2009), and it was emphasized to the respondents that they were being interviewed as representatives of their institution. The themes for the interview included how the university viewed its position in society, and the current focus on excellence, competitiveness and internationalization. Furthermore, the set of questions focused on rankings and how rankings are used: what the views on rankings are, their importance for strategic decision-making, and whether concerns about ranking positions rankings had led to any institutional measures/initiatives. The interview guides were inspired to some extent by previous research in the field (see, e.g. Marginson and Sawir 2006; Hazelkorn 2011). The interviews were conducted in March 2014, either in person or as telephone interviews.

Furthermore, examining how universities communicate ranking results to the public also shows a particular preference in terms of the image that the university conveys. For this purpose, we have examined how these universities represent rankings on their websites. While we acknowledge that this does not always represent a direct linkage to strategy, identity as such is not constructed only through strategic choice. By creating certain mythos and symbols (i.e. we are the best university in the country/region), such representation can also contribute to organizational identity.

This methodological approach has its limitations and trade-offs. The interview data are focused on the current state of affairs and as such only provide a snapshot, so any causal claims of impact should be considered with caution. The relatively large number of cases also compromises the depth of analysis to a certain extent, as our focus was quite broadly at the institutional level. Furthermore, only one Finnish university has been included in the sample, while several universities have been included among the cases in Sweden, Norway and Denmark. However, this illustrates differences in higher education systems, as Finland has one higher education institution that is far larger than all the others (Aarrevaara et al. 2009). We also focus on senior leadership of the institution and as such one gets a rather top-heavy picture of the institutions from such an approach. We also acknowledge that any strategic plans pitched at the institutional level might be rather loosely coupled to reality at the grass roots level. However, we nevertheless believe that the benefits of comparing 14 institutions across a whole region sufficiently compensate for this trade-off of more comprehensive single case studies without the comparative element. As the purpose of this paper is to examine the broad developments in the Nordic countries in the light of recent changes in these systems, it was deemed more appropriate to include a set of cases in the analysis that was as wide as possible.

Challenging identities?

National context as a source for variation?

The Nordic countries are often seen as being quite similar, but when it comes to research policy, they have chosen slightly different paths. All countries have a different form of excellence initiatives, and they are shaped and oriented differently (Gornitzka and Maassen 2011). Norway has had a focus on development of excellence initiatives at the national level through several forms of schemes to promote larger research groups that are or have the potential to perform well. Finland has also had national excellence initiatives, although these have focused more on creating networks between institutions. Excellence initiatives in Denmark have channelled funds to individuals and smaller research groups, much in line with the modern excellence policy developed by the European Research Council. This has probably contributed to the number of more highly visible and cited researchers in Denmark. Sweden has chosen a pathway in between, with a mix of the two strategies. These differences in research strategies and how excellence initiatives are structured in the Nordic countries may have had some implications for the differences in position on the rankings. However, of most interest to the current study, the excellence initiatives in the Nordic countries may have triggered curiosity among Nordic universities as to “what works” and how specific forms of organizing excellence initiatives create specific results.

Another source of variation within the higher education landscape in the Nordic region is institutional size. Sweden and Denmark have some very large higher education institutions, and University of Helsinki in Finland is significantly larger than all other institutions in that country. As size of institution matters in some of the rankings (i.e. ARWU), this may also contribute to explaining some of the differences in positioning, but also with respect to who to benchmark against.

But even though there are differences between the Nordic countries, both in size of higher education institutions and in how their research policies have been structured, they are still all operating in a setting where most institutions are public and there is a comparably low level of hierarchical difference between institutions within each higher education system (Aarrevaara et al 2009). This is also the background for the argument that these types of institutions may be able to withstand pressure from global competition to a greater extent. In addition, within the Nordic region there is quite a long history of cooperation in higher education going back to 1952 and the establishment of the Nordic Council (Maassen et al 2008). Through collaborative schemes such as Nordplus—an exchange programme for students in the Nordic region, Nordic universities have established solid inter-institutional links that could open up for possible benchmarking activities between them, also with respect to strategic initiatives. As such, one could argue that although there indeed are many differences between the Nordic countries concerning the way they organize their higher education and research systems, there is still strong cultural and historical ties between the countries and between their universities (Maassen et al 2008).

Environmental push towards excellence and relevance

While there were some variations across the Nordic countries, the case studies also identified differences in the perceived institutional environment within countries. In Norway, all four institutions have clear priorities to stimulate excellent research, with ambitions of being world-class in certain narrow areas. This is being done primarily through using Research Council instruments such as Centres for Excellence. The traditional research universities in Norway all believe that their opportunities to focus on excellence are sufficient and that there are no financial or regulatory barriers for such a focus. Being excellent is also of high priority in all institutions, while various instruments have been introduced at the institutional level. While the University of Tromsø is sharpening its unique Arctic profile, the University of Oslo is focusing heavily on research management and the development of strategic advisory boards. All of these four old comprehensive research universities report on the measures being taken to facilitate and further develop their world-class research.

In Denmark, current regulatory and funding situation was described as being extremely favourable. While certain limitations in terms of wage caps and hiring procedures are mentioned, the current regulatory and financial environment was evaluated as being good, described by one respondent as:

right now we are standing at the top of the Himalayas funding wise. It can only go down.

One of the institutions actually mentioned that too much external funding was being brought in, and that this had too much influence on the opportunities to set institutional priorities in terms of research themes. Furthermore, national policies for excellence were mentioned and highlighted as a “secret of the Danish impact” in terms of their relative success in bibliometric indicators. While funding from Horizon 2020 and the European Research Council are high on the agenda in all Nordic countries, Denmark stands out as the country where this focus is the most pronounced. In Sweden, concentration of resources was noted in the interviews. Again, national priorities for excellence play a role, through the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet) and the Wallenberg Foundations, public private foundations that fund excellent research in Sweden. However, international competition for the top researchers is noted:

some of our top researchers have received offers they could not refuse—from Oxford, Cambridge or the US. They have picked some of our best researchers in the last 10 years.

In the case of the University of Helsinki in Finland, it is perhaps the most dominant in the Finnish national context in comparison with the other case universities. Again the institutional environment was evaluated as enabling, whereas the issues that were highlighted as being problematic were more closely linked to disciplinary cultures where a shift towards more international publishing is still underway.

Do rankings trigger strategic actions at the university level?

When asking university leaders and other key people about the role of rankings, the uniform response was that it is quality improvement that counts, not rankings. Any improvement in ranking positions should only be a side effect of such general quality improvement. One of the respondents actually compared this to getting a medal in the decathlon while only competing in the shot put and 1500 m. There is a feeling that focus on such single aspects of quality would not improve overall performance, but improved performance on few indicators would. There was also a strong argument that focusing on rankings would not satisfy the societal mandate of the universities. However, institutional representatives acknowledge that certain parts of rankings might be used for information purposes and that rankings in some cases are used for benchmarking.

While rankings are not commonly mentioned in the universities’ strategic plans, there are a few exceptions. The University of Helsinki has a clear goal of being in the top 50 in the world. However, the decision to include a specific ranking goal came from the university board:

our board decided that we would need a very concrete goal, because it is good to have an ambitious goal. It shows we want to be better, but the real ambition was to put it down in writing. I personally did not like that too much, because you know it varies, there are many fluctuations, (…) but when thinking about it more I think it’s a good thing, it really gives a focus on where we want to be. This says more than we want to be a top university—well we are a top university already so it makes it concrete.

Including rankings in the strategic plans was also the case for DTU and the University of Southern Denmark (SDU). DTU’s goal is to be among the top five of the technical institutions in Europe, and SDU’s ambition is related to research output in the Leiden ranking. These two institutions and the University of Helsinki are also outliers in terms of including actual ranking position goals in their strategic plans. In some of the other strategic plans, high positions in rankings are mentioned, but with no operationalization about what this means nor is there focus on instruments that could be used to achieve these goals. Furthermore, some discrepancy in terms of what is stated in the strategic plan and the institutional realities was recorded. At some of the Swedish institutions, focus on rankings was not visible in the strategic plans, but at the institution active work with rankings was taking place. This suggests that to a certain extent, actively working with rankings is dependent on particular entrepreneurs within the organization, and as such rankings are not institutionalized as a legitimate tool for information.

In Norway, one can identify a varied level of ambition in terms of rankings. Overall, rankings as a phenomenon are met with some indignation as there is a widespread understanding that the geographical positioning of Norway makes it difficult to be very successful in rankings. The younger institutions in all the Nordic countries are also conscious of their difficulties in achieving high reputation scores, as “age matters” for reputation. Reputation surveys are therefore scrutinized, and a few of the interviewees expressed strong criticisms about the methodologies employed. Few institutions mention having any institutional measures that are directly related to or derived from the rankings.

At the same time, some institutions have measures that can be seen as being indirectly linked. First, some of the Swedish institutions have created a managerial position that can be loosely translated as “reputation analyst”. Occupants of these positions work primarily on gathering data for rankings and assuring that quality data are delivered to different ranking proprietors. In some ways, the very establishment of such a position can be seen as a strategic decision to work on rankings. Establishment of such a position or unit can also become increasingly professionalized over time and creates a place for rankings on the organizational map. Such positions do not exist in other Nordic countries where this is usually one of the tasks of an administrative employee and not a full-time position. Further, the institutions also report an increased focus on getting researchers to document their publications in electronic databases. However, this cannot solely be accounted for as being linked to rankings, since there is strong focus on research outputs in general in all of the Nordic countries. Nevertheless, SDU did take a direct initiative to examine how to achieve the best possible bibliometric outputs, by sending some librarians to Leiden. Therefore, while there appears to be caution in terms of using rankings as a basis for strategic decisions, at the same time there are some signs of practices in some of the institutions that could be linked to efforts to improve rankings, and it is clear that ranking performance is followed.

While using rankings to create a profile of one’s own university was not very widespread, there was widespread use of rankings for initial screening of possible partner institutions. While it was highlighted that in many cases the initiative for cooperation agreements comes bottom-up, many academic leaders also acknowledged that they would use rankings for initial screening of requests, incoming guests and similar situations. The leaders also reported experiencing screening themselves when abroad. As such, it appears that rankings have gained some legitimacy as an instrument for screening partner institutions. While our data do not suggest that rankings are used for strategic decision-making within the institution, they have become a convenient part of the toolbox used for navigating in the global higher education landscape, despite their faults.

Overall, our case institutions show a strong focus on quality. While rankings are criticized, there is also acknowledgement that there is a need for information in the benchmarking process. While one can criticize rankings for their poor selection of indicators, at the same time rankings may fill a certain information need in the institutions. In Norway, institutions that are not represented in the global rankings, such as institutions taking part in the meeting of the Norwegian Association for Higher Education Institutions, also express the need to get benchmarking information. These institutions would refer to the national student survey (Studiebarometeret) published by the National Quality Assurance Agency (NOKUT) as a means to identify individual positions in the institutional hierarchy, something that can be seen as a proxy for a rankings position. This suggests an institutional need to make sense of one’s positioning and gain more information about performance. To what extent rankings are the most appropriate means to deal with this information vacuum is of course another story.

Are rankings challenging the identity of Nordic research universities?

Taking into account the traditional values of the Nordic research universities and the emerging focus on excellence, our key question has been to what extent global rankings has an effect on institutional identities, the collective “who are we” and “who do we want to be”?

Examining our case institutions and their strategic plans, it is clear that focus on quality and excellence are indeed high on the agenda. This focus can on the one hand be linked to national policies with focus on excellence, and on the other hand to various institutional factors and legacies. All of these institutions view themselves as players in a global knowledge arena and not merely in a national context. Being world-class in certain areas is an integral part of the value system and arguably a part of how these institutions view themselves. The respondents were also clear about the need to document results for society and show that institutions are accountable. This is also perhaps to be expected in the Nordic higher education systems, where social responsibility is still an important and shared value for the universities. While all of the institutions have the aim in one way or another to be world-class in something, in the Nordic institutions the idea that higher education is a public good and as such, a concern for society seems still very much alive. One could therefore argue that there is also a specific Nordic dimension. It was also noted in the interviews that it is not always easy to combine a strong focus on basic research and excellence, and as such, two competing ideas in the way institutions view themselves can be identified.

As the internal strategic use of rankings is limited, rankings can function is as a means for and re-enforcement of external status. An example of this is the quote from the University of Helsinki highlighted earlier in this section—by setting the ambition level more specifically, universities can communicate beyond being a “top university”. Even if not explicitly used for profiling, rankings are also visible on the university websites. Both on the websites and in the interviews, it is in particular the three big schemes (ARWU and THE that are discussed in this paper, alongside QS) and the Leiden ranking that are mentioned, with three institutions also highlighting the Taiwan ranking.

One of the starting assumptions in this study was that one could presume that institutions that perform well would also focus more on rankings. While there was a tendency towards such a pattern, this was not clear cut. In the three institutions in which specific goals were set (DTU, SDU and University of Helsinki), the interview respondents appeared to consider such specific goals as being of more symbolic value for explaining the kind of institution the university is, thus ranking position was a signifier of being a part of a specific group of institutions rather than a goal in itself.

Overall, our data suggest that there are few signs that rankings challenge and change university identities. One key argument here was that while institutions do have benchmarking needs, it was emphasized in the interviews that for those universities which are part of the rankings, the information displayed is not really novel. There is much tacit knowledge within higher education about which the “good” institutions are—even worldwide. As such, one can identify much implicit knowledge about the global educational landscape. The same argument applies at the national level as in many cases, rankings re-emphasize existing national hierarchies. The flagship universities are usually in the capital and are the oldest and/or largest institutions. A somewhat divergent case here is Sweden, where both Lund University and Uppsala University are very old institutions, and neither them nor Stockholm University is a clear flagship institution that would dominate the others. This is in contrast with the Universities of Copenhagen, Oslo and Helsinki. As such, the higher education hierarchy seems somewhat more open in Sweden, and organizational identities related to relative prestige of institutions in this country seem not so settled.

An interesting case emerged in Norway in 2010 when the University of Bergen was ranked higher than the University of Oslo in one of the global rankings, due to an error in the data. This created a huge national debate and media attention. This was also a good example of what can happen when a ranking considerably challenges existing national hierarchies. As long as the rankings do not “rattle the cage”, their effect on universities’ self-perception in terms of prestige on the national higher education landscape is also not challenged. There is some consideration in terms of the Nordic comparative dimension and positioning in the global market. While all of the Nordic institutions we examined report that they experience fairly positive regulatory and funding conditions to support excellence—it nevertheless shows that there is considerable difference between the Nordic countries in terms of research performance.

Conclusion

The current study was embedded in the discourse about globalization, and how rankings can be said to be a reinforcing globalized element influencing higher education. While there is evidence that suggest the substantial impact of rankings on university behaviour in different parts of the world (Marginson and Sawir 2006; Hazelkorn 2011), our study can be said to offer a somewhat different picture. Expectations that suggest a strong emphasis on global rankings in the Nordic higher education landscape cannot be said to be substantiated. Although Nordic universities indeed pay attention to global rankings by providing space for rankings on their own webpages, and even where a couple of universities have made explicit references to rankings in their strategic plans, the overall picture is one of a quite moderate interest in rankings and a moderate interest among institutions in making strategic efforts to change their ranking position. Existing university identities are still basically maintained, although tendencies towards selective use of rankings on certain issues can be identified.

Coming back to our three perspectives on rankings as identity signifiers, our study suggests that rankings in the Nordic region are mostly consolidating although sometimes challenging existing university identities. Our data do indeed indicate some “peer watching” tendencies among the universities as suggested by the perspective of university identities are externally given (Gioia et al 2000). However, much of this activity is focused on other Nordic universities, and with limited mentioning of universities outside the region. Interviews showed that the selected universities were well aware of each other’s initiatives and strategies and that universities with similar identities were followed closely. Here, rankings functioned as one source of information, but in a process that has been taking place for decades before the rankings appeared on the horizon. Hence, institutions did follow each other before rankings emerged, but rankings have made it easier to keep up with other institutions. As such, this finding supports assumptions that rankings may create “identity clusters” and as such contribute to a more stratified higher education system.

In a similar vein, one can also see that rankings may strengthen and reinforce institutional, domestic and regional priorities as suggested by the second perspective where university identities are seen as historically developed (Albert and Whetten 1985). While a number of the universities in our sample are quite active in developing their distinct profile in a more competitive environment, a common denominator in these initiatives is the emphasis on the historical “saga” and the unique identity of the individual university (Clark 1972). Here, results from rankings are used to underline the historical characteristics and positioning of the universities, although rankings sometimes may produce outcomes that also can challenge such positions.

Our third perspective, where identity construction is seen as a more selective process, also finds some support in our data. All institutions in our sample are research-intensive universities, and most of them are well-placed within global rankings. As such, these institutions see the current global, national and regional excellence agendas as fitting well with their current identities, although the rankings certainly seem to increase the attention paid to excellence. Here, one could suspect that an increased focus on excellence fit well with the long-term strategies of the universities and that it is in their interest to boost the public interest in supporting excellence, not least with respect to national funding schemes (Glynn 2008). The current study is qualitative and does not allow for strong generalizations. However, the study adds nuance to the picture about the scope and pace of globalization, at least when it comes to how universities operate in an environment in which rankings are highly visible. As we have shown, rankings may play different roles in the identity construction of universities. While one could argue that we have only studied a region that is “lagging behind” in the race for a more globalized higher education sector, and where the results might be different a few years’ time, it is also important to underline that other studies of identity emulation have also demonstrated quite substantial differentiation (see, e.g. Labianca et al. 2001). Our study can be said to question whether global rankings have particularly strong isomorphic consequences on the higher education sector. In the Nordic region, global university rankings do not seem to contribute to a radical change in the identity of universities that historically have been quite strongly research-oriented—although perhaps not in the ways promoted by Shanghai and THE. As such, it seems that global rankings in this region can contribute to further strengthening of existing identities of the universities.

Notes

In addition, some of the better-known rankings systems include QS World University Rankings, Leiden ranking, Taiwan ranking and U-Multirank.

References

Aarrevaara, T., Dobson, I., & Elander, C. (2009). Brave new world. Higher Education Management and Policy, 21(2), 1–18.

Albert, S., & Whetten, D. (1985). Organizational identity. Research in Organizational Behavior, 7, 263–295.

Becher, T., & Trowler, P. (2001). Academic tribes and territories: Intellectual enquiry and the culture of disciplines. Buckingham: Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press.

Bogner, A., & Menz, W. (2009). The theory-generating expert interview: Epistemological interest, forms of knowledge, interaction. In A. Bogner, B. Littig, & W. Menz (Eds.), Interviewing experts (pp. 43–80). Palgrave/MacMillan: Houndmills.

Castells, M. (2001). Universities as dynamic systems of contradictory functions. In J. Muller, N. Cloete, & S. Badat (Eds.), Challenges of globalization. South African debates with manuel castells (pp. 206–223). Cape Town: Maskew Miller Longman.

Christensen, T. (2011). University governance reforms: Potential problems of more autonomy? Higher Education, 62(4), 503–517.

Clark, B. R. (1972). The organizational saga in higher education. Administrative Science Quarterly, 17(2), 178–184.

Clark, B. R. (1983). The higher education system: Academic organization in cross-national perspective. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Deem, R., Mok, K. H., & Lucas, L. (2008). Transforming higher education in whose image? Exploring the concept of the ‘world-class’ University in Europe and Asia. Higher Education Policy, 21(1), 83–97.

Dill, D. D., & Soo, M. (2005). Academic quality, league tables, and public policy: A cross-national analysis of university ranking systems. Higher Education, 49(4), 495–533.

Gioia, D. A., Schultz, M., & Corley, K. G. (2000). Organizational identity, image, and adaptive instability. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 63–81.

Glynn, M. A. (2008). Beyond constraint: How institutions enable identities. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, R. Suddaby, & K. Sahlin-Andersson (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 414–430). Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Gornitzka, Å. (2013). Channel, filter or buffer? National policy responses to global rankings. In T. Erkkilä (Ed.), Global university rankings: Challenges for European higher education (pp. 75–91). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gornitzka, Å., & Maassen, P. (2011). University governance reforms, global scripts and the “Nordic model”: Accounting for policy change? In J. Schmid, K. Amos, J. Schrader, & A. Thiel (Eds.), Welten der Bildung? Vergleichende Analysen von Bildungspolitik und Bildungssystemen (pp. 149–177). Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Harvey, L. (2008). Rankings of higher education institutions: A critical review. Quality in Higher Education, 14(3), 187–207.

Hazelkorn, E. (2011). Rankings and the reshaping of higher education. The battle for world-class excellence. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hazelkorn, E. (2013). How rankings are reshaping higher education. In V. Climent, F. Michavila & M. Ripollés, (Eds.), Los rankings universitarios, Mitos y Realidades. Tecnos. http://arrow.dit.ie/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1023&context=cserbk. Accessed May 11, 2015.

Kehm, B. M., & Stensaker, B. (2009). University rankings, diversity, and the new landscape of higher education. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Labianca, G., Fairbank, J. F., Thomas, J. B., Gioia, D. A., & Umphress, E. E. (2001). Emulation in academia: Balancing structure and identity. Organization Science, 12(3), 312–330.

Liu, N. C., & Cheng, Y. (2005). The academic ranking of world universities. Higher Education in Europe, 30(2), 127–136.

Maassen, P., Vabø, A., & Stensaker, B. (2008). Translation of globalisation and regionalisation in Nordic cooperation in higher education. In Å. Gornitzka & L. Langfeldt (Eds.), Borderless knowledge. Dordrecht: Springer.

Marginson, S. (2014). University rankings and social science. European Journal of Education, 49(1), 45–59.

Marginson, S., & Sawir, E. (2006). University leaders’ strategies in the global environment: A comparative study of Universitas Indonesia and the Australian National University. Higher Education, 52(2), 343–373.

Marginson, S., & van der Wende, M. (2007). To rank or to be ranked: The impact of global rankings in higher education. Journal of Studies in International Education, 11(3–4), 306–329.

Pedersen, J. S., & Dobbin, F. (2006). In search of identity and legitimation: Bridging organizational culture and neoinstitutionalism. American Behavioral Scientist, 49(7), 897–907.

Piro, F. N., Hovdhaugen, E., Elken, M., Sivertsen, G., Benner, M., & Stensaker, B. (2014). Nordiske universiteter og internasjonale universitetsrangeringer: Hva forklarer nordiske plasseringer og hvordan forholder universitetene seg til rangeringene? NIFU rapport 25/2014. Oslo: NIFU.

Saarinen, T., & Välimaa, J. (2012). Change as an intellectual device and as an object of research. In B. Stensaker, J. Välimaa, & C. S. Sarrico (Eds.), Managing reform in universities: The dynamics of culture, identity and organizational change. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Salmi, J. (2009). The challenges of establishing world-class universities. Washington, DC: Wold Bank.

Selznick, P. (1957). Leadership in administration: A sociological interpretation. New York: Harper & Row.

Stensaker, B. (2015). Organizational identity as a concept for understanding university dynamics. Higher Education, 69(1), 103–115.

Välimaa, J. (1998). Culture and identity in higher education research. Higher Education, 36(2), 119–138.

Yorke, M. (1997). A good league table guide? Quality Assurance in Education, 5(2), 61–72.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The paper draws on a recently finalized project funded by the Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research that focused on (a) deconstruction of ranking lists; (b) the effect of rankings on organizational behaviour.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Elken, M., Hovdhaugen, E. & Stensaker, B. Global rankings in the Nordic region: challenging the identity of research-intensive universities?. High Educ 72, 781–795 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9975-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9975-6