Abstract

The lack of economic sustainability of most healthcare systems and a higher demand for quality and safety has contributed to the development of regulation as a decisive factor for modernisation, innovation and competitiveness in the health sector. The aim of this paper is to determine the importance of the principle of public accountability in healthcare regulation, stressing the fact that sunshine regulation—as a direct and transparent control over health activities—is vital for an effective regulatory activity, for an appropriate supervision of the different agents, to avoid quality shading problems and for healthy competition in this sector. Methodologically, the authors depart from Kieran Walshe’s regulatory theory that foresees healthcare regulation as an instrument of performance improvement and they articulate this theory with the different regulatory strategies. The authors conclude that sunshine regulation takes on a special relevance as, by promoting publicity of the performance indicators, it contributes directly and indirectly to an overall improvement of the healthcare services, namely in countries were citizens are more critical with regard to the overall performance of the system. Indeed, sunshine regulation contributes to the achievement of high levels of transparency, which are fundamental to overcoming some of the market failures that are inevitable in the transformation of a vertical and integrated public system into a decentralised network where entrepreneurialism appears to be the predominant culture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The lack of economic sustainability of the healthcare systems in many developed countries and a higher demand for quality and safety has contributed to the development of regulation as a decisive factor for modernisation, innovation and competitiveness in the health sector [25].

Regulation has two essential aspects in the health sector. It intends to guarantee appropriate competition, namely in the context of a quasi-market where different providers apply for the public financing of their healthcare activities. The government by contracts is the paradigm of this type of service, where the guarantee of the quality of the services offered is more important than the institutional nature of the providers [12]. The economic regulation intends to correct the market failures in this sector which need constant and persistent supervision: namely, information asymmetry, externalities, service scarcity, market uncertainty and monopoly creation. Healthcare regulation intends also to safeguard the basic rights of the citizens, namely in what concerns the practice of cream-skimming or even the induced demand of healthcare that leads inevitably to over treatment. The social regulation is then an instrument that affirms the basic rights of the patients.

The main objective of this paper is to determine the importance of the principle of public accountability in healthcare regulation, stressing the fact that sunshine regulation is vital for an effective regulatory activity, for an appropriate supervision of different providers, to avoid quality shading problems and for healthy competition in this sector. Methodologically, the authors depart from Kieran Walshe’s [26] regulatory theory that foresees healthcare regulation as an instrument of performance improvement and they articulate this theory with different regulatory strategies. Although this theory acknowledges four key characteristics that are central to the nature of regulation—formal remit, centralisation, third party accountability and action in the public interest—independence can only be achieved if there are appropriate mechanisms for public and stakeholder accountability.

This is probably the innovative contribution of this paper because sunshine regulation and the role of public accountability in this setting should be stressed as a major factor of improvement in healthcare and of empowerment of society. A secondary objective is to demonstrate that sunshine regulation works whatever the regulatory strategy followed. The authors try to find out if compliance, deterrence or responsive strategies are better off with accountability as a main driver of success in healthcare regulation.

Accountability and Regulatory Strategy

The high complexity of the healthcare system has contributed to the need for effective accountability by the healthcare providers so that two essential objectives in the health sector are achieved [18] namely to promote a healthy competition among the operators and to achieve important social values such as the right to information and to freedom of choice. To achieve these objectives, the application of the principle of public accountability is essential to fight against the existence of encrypted data and allow the publicity of performance indicators of the healthcare organisations. Namely evidence-based performance indicators (social, economical and quality) are necessary to fulfil these objectives.

The term accountability refers to the need to make the decision process in healthcare visible and transparent as well as to the method for achieving this objective. At all levels of the healthcare system important decisions are taken with regard to the quantity and the way in which the resources are used. According to Norman Daniels the manner in which these decisions are made is an important way for evaluating the fairness of a health system [10]. This means, each citizen has the right to know the underlying drivers of the decision-making process and, furthermore, to be an active partner in this process [8]. This partnership implies that information asymmetry is reduced through the informed consent practice, although the patient/physician relationship will always be directed by professional values. Regulation can play a major role in this setting by guaranteeing that patients are informed of their clinical conditions. At a macro level it refers to the concept of “democratic and transparent process” and to promoting the participation of the society who, in accordance with unanimously shared values, has the required wisdom to decide on this as well as on other areas of social importance.

The term “accountability” has, from the point of view of political philosophy, two distinct though related aspects. By public accountability we understand the duty to involve both the society in general as well as the citizen in particular in the decisions related to healthcare. Thus the organisations are obliged to provide data and indicators so that the citizen may be free to make informed choices [9]. Democratic accountability refers to the process by which the health institutions—whether it is the Government, a hospital or an individual provider—account to society [7]. This may involve the drawing up of periodic reports, the execution of internal and external audits, or even the justification of a determined course of action, namely when the adoption of guidelines in clinical practice is at stake. In Table 1 the different levels of the implementation of accountability are presented.

Accountability also refers to the principle of autonomy, not only at the individual level but also collectively; social autonomy in relation to the institutions with (or without) democratic legitimacy and the promotion of the right to information of one and all citizens. There does not seem to be a real alternative, since in a plural and democratic society, no manager can meet the expectations of the various cultural groups, an indispensable factor to promote social cohesion. Thus, for example, on deciding to allocate resources for a clinical intervention that benefits a wide segment of the population disregarding another treatment that benefits only a small minority (orphan diseases for instance), the only fair process is the resort to deliberative democracy through the active and informed participation of the society. Progressively, the systematic consultation with an informed public, its involvement in critical decisions and the establishment of partnerships in the decision-making processes, exemplify the reactive nature of the citizens on decisions about the health policy. Fairness, from a Rawlsian perspective [20, 21], means that the empowerment of society and the subsequent social choices comply with the principle of equal opportunities. It follows that deliberative democracy should abide to fundamental values of liberal democracies and the rights of minorities must always be protected by the majority vote, namely ensuring that their voices are heard through the active role of patient advocacy groups, a fundamental step in modern societies for scrutinising many government decisions.

The different accountability levels, from the individual provider to the top manager of the healthcare system, are related to the different types of society’s participation in the democratic process. And, as Norman Daniels suggests [29] “one aspect of public accountability is to undertake careful, scientific assessments of the performance of the system as a whole and its various components. Public reporting of these outcome measures is likely to be perceived as threatening to some interests. But a refinement of this sort of evaluation is an essential mechanism for improving the system and relying on consumer choices to force such improvements in quality” (p. 58). Many healthcare agents, individual practitioners, as well as institutions and healthcare plans, have specific interests that call for encryption. However, in the long run, the inevitable competition in the healthcare sector implies that both quality and economic performance indicators are publicly accessible. The availability of this kind of data on the internet for public consultation is an example of the importance of the principle of public accountability. Such a practice was implemented both by the British Care Quality Commission as well as by the Portuguese Regulatory Authority of Health.

It is beyond the scope of this paper to analyse in depth the regulator’s institutional nature both in a true healthcare market and in a virtual competitive market. However, for sunshine regulation to be effective the principle of public accountability should be considered by any regulatory strategy. Classically, there are two principal models of intervention of regulatory activity. Compliance, which means generating the operators’ agreement to the regulator’s objectives, and deterrence, which suggests a coercive attitude hindering performance, appealing to the mechanisms legally established for this purpose. The two models and the corresponding regulatory strategies are not mutually exclusive, quite on the contrary. Moreover, there are some organisations that comply with voluntary codes of conduct. Nevertheless, different realities originate the need to use the models in a casuistic manner [13]. The healthcare market’s atomicity should lead, in principle, to intervention at the deterrence level, due to the regulator’s difficulty in supervising all the providers. For instance, the numerous physicians’ offices in a liberal regime; while, on the other hand, the existence of a reduced number of operators is more predisposed for compliance.

The expected consequences of the action also deserve a different model of approach. For example, while adverse patient selection and cream-skimming should deserve a firm and determined intervention, possibly resorting to legal sanctions, other milder deviations should only be subject to regulatory prevention. So, the choice of the regulatory model is related to the existence of a set of conditions favourable for the production of effective results [24]. The compliance model applies to providers with a strong ethical and organisational culture, but it is well proven that these organisations are not always effective in complying with their objectives, or efficient in resource allocation. This model specifically requires guidelines, codes of conduct, statements of rights and general recommendations for certain performance standards to be complied with. An inconvenience of the systematic implementation of compliance, as a regulatory operational model, is the likelihood of the development of the phenomenon known as creative compliance.

Creative compliance refers to the possibility of developing a formal adjustment between the regulatory objectives and the regulators’ practices, without the required compensation with regards to performance improvement [3]. That is to say, an undesirable consequence of the compliance model is the apparent compliance with the recommendations issued, generating added costs for the healthcare organisation without the corresponding change in its organisational culture. The institution adapts with a great deal of creativity to the required standard, without the evidence of improvement in the performance or quality of the services rendered. The regulated organisation’s strategy may, eventually, entail the formal compliance of the recommendations issued by the regulator, underestimating the adjustment to new requirements of the healthcare system. For this reason, it is understood that compliance is in itself not an effective healthcare regulatory model; however, and although other supervising mechanisms are also necessary, the more publicity there is on the activity of the healthcare providers the more probable will the success of this model be. Public accountability is therefore a driver to a compliance strategy.

So compliance should not be underestimated as a dissuasion tool for condemnable practices. Even less should it be considered as a type of “soft regulation”. In a framework of supervision, the power of prevention and early intervention has, as in other areas of the social and economic activity, an important role in the regulatory system. However, compliance as a regulatory strategy will be much more effective if the operators provide publicly the required information; and therefore, it might not be necessary to resort to more aggressive sanction mechanisms and practices (deterrence).

The deterrence model is specially intended for providers that are predisposed to do everything they can to achieve their goals [6]. The structural reform of the healthcare system contributed to a highly competitive environment, with considerable financial investments and progressively low profit margins. With the opening of the public healthcare system to private operators (for-profit and not-for-profit), and the corporatisation of hospitals and primary care, the competition for the health market may generate dysfunctions that clearly need to be regulated. Moreover, it is probable that in these cases public accountability can be manipulated according to the interests of the healthcare providers.

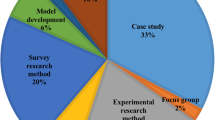

The ideal regulatory strategy seeks to integrate both perspectives. It is a third model that aims at a systematic balance between compliance and deterrence. This combined model is called responsive regulation [1]. Thus, a graded hierarchy of responses for non-compliance with the recommendations and directions of the regulating entity develops. This enforcement pyramid intends to develop the regulators’ capacity to adapt to the current circumstances (Fig. 1). The adopted model is not static but rather dynamic, depending on the various circumstantial factors.

Responsive regulation (Adapted from Ayres and Braithwaite) [1]

Responsive regulation presupposes that cultural diversity between regulated organisations justifies the use of a discriminatory power. That is, the organisations are distinct and, as such, should be dealt with in a differentiated way. Since contingency is the base of this model, hierarchy in the use of regulatory tools is fundamental. It is not possible to consider a standard use. To effectively regulate organisations’ practices an evaluation of each particular situation is justified followed by the intervention with the appropriate regulatory instruments. It is possible then to grade regulation measuring instruments since the latter have a more significant weight, both in financial resources and in technical and material resources, when the organisations’ performance is weak. This notion is related, in part, to the concept of empowerment associated with regulation.

That is, an effective regulatory system should be developed with the purpose of improving the performance level of the organisations, with characteristics such as contingency and hierarchy contributing decisively. The entities responsible for regulation resort to distinct mechanisms depending on the organisations’ performance level and collaboration with regulatory authorities [2]. When there are signals that show “bad” behaviour which puts compliance at risk, correction measures will be introduced and these will increase whenever there seems to be lack of efficiency in the “milder” measures. The lack of accountability is one of the reasons that leads necessarily to a reinforcement of the regulatory instruments and, therefore, of deterrence as a regulatory strategy.

At the base of the pyramid there are recommendations and guidelines indicating the standard to be followed by the regulated entities. These will be for more frequent and general use in the regulatory activity. It is fundamental that all regulatory instruments and the regulators’ discretionary power are subject to some moderation by criteria, such as prudence, transparency and accountability. Furthermore, the adopted procedures should be standardised and grounded on coherence and consistency, so that the innovating nature of the regulator is not confused with lack of determination. This means that an integrated vision of the objectives of the healthcare regulation and of the means to achieve it is an important stimulus for the regulatory activity. Especially responsive regulation depends on the systematic application of accountability arrangements so that it is possible to achieve an effective sunshine regulation and, in this manner, allow the introduction of new governance models more concerned with the citizens’ interests [27].

Sunshine Regulation in Healthcare

The successive reforms in the healthcare systems of the developed countries have in common the fact that maximising efficiency is considered a factor as important as the guarantee of adequate performance levels in the access to and quality of healthcare [23]. Besides these important drivers of the reform of healthcare institutions, the liberal democracies, namely European countries, resort to other criteria, namely, the fact that the healthcare system should take into consideration citizens’ perceived needs. Responsiveness is then a fundamental factor of any healthcare reform in the attempt to incorporate the citizens’ expectations in the main features of the reform. Nevertheless, responsiveness, or rather the capacity to meet the citizens’ wishes, is normally confronted with a problem of information asymmetry due to the specificity of the economic good at issue. It is especially important that a distinction is drawn between fundamental needs and “preferences” and an adequate regulatory framework can effectively draw these distinctions as long as the rationale for prioritising is fair and publicly accountable.

Healthcare regulation is rising steadily in many countries and for different reasons. In particular economic, social, political and organizational causes paved the way to stronger healthcare regulation. An example of this evolution is the creation in April 2009 of the British Care Quality Commission. Both in healthcare systems based mainly on the competitive market, such as the US system, and in the public systems such as the National Health Service, the regulatory framework has developed significantly in the last years, at least in part because competition exists almost everywhere. The search for efficiency may easily cause malfunctioning of the healthcare services that needs to be regulated and supervised [4]. Diverse institutional formats are acceptable with different degrees of independence in relation to the Government [17]. Indeed without regulation the risk of providers’ abuse is higher as they take advantage of their dominant position or market power, providing services of lower quality and higher prices. So, what is really at issue is a change of paradigm, according to which the concept of State itself is questioned so that it is possible to implement the statutory regulation in various sectors of the economic activity. This evolution took place in the majority of the OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) countries and is a central element in the development of the Regulatory State [15, 16]. However, the main issue is to determine if regulation really works and how its main objectives may be achieved. As stated by Kieran Walshe four key characteristics are central to the nature and purpose of regulation (p. 20–21):

Formal remit or acknowledge authority. In any system of regulation, the regulator has to have some kind of formal remit to regulate that is acknowledged by other stakeholders, most obviously the organizations being regulated. …

Centralisation of oversight. Regulation represents a centralization of responsibility, power and oversight in the regulator … The regulator is regulating on behalf of others such as corporate purchasers, funders, consumer groups, individual consumers and wider society, who cede some powers to the regulator in exchange for an undertaking, implicit or explicit, that the regulator will act in their interests …

Third-party accountability. As a result of the centralisation referred to above, the regulator is always a third party to market transactions or inter-organizational relationships. In a market setting, the regulator is a third party to market transactions, providing a framework within which they take place and acting to constrain the actions of buyers and sellers. In non-market settings the regulator is still a third party to the inter-organizational relationships and accountability arrangements. There will always be some kind of reporting, performance management or accountability chain through which an organization is overseen, but the regulator sits outside that chain of command or bureaucratic hierarchy.

Action in the public interest. …the process of regulation is intended to serve some wider societal goals, often established or expressed by the government” [30].

The authors will focus specially on the need for accountability by the provider; this means they will stress the importance of sunshine regulation. Accountability (public display) and benchmarking (regular comparison) of a set of performance indicators promotes a yardstick for competition between providers and leads to performance improvement. In general, there are two essential aspects that characterize a transparent and accountable regulation:

-

1.

Application of benchmarking: Through the comparison of a set of performance indicators it is possible to compare the economic, financial and quality results of various healthcare providers. The star rating of hospitals implemented by regulatory agencies is an example of this benchmarking;

-

2.

Public discussion of performance: The application of the principle of public accountability implies that the results of the benchmarking analysis are made public and scrutinized by society. In this manner, freedom of choice and competition in the healthcare system are promoted as well as the citizens’ empowerment.

Public accountability is, more than a performance principle, the main driver of a new culture in the health sector; independently of the degree of the State’s intervention and the introduction of the market rules, it needs to be applied effectively so that the objectives of the healthcare system are fully achieved. In particular, the sunshine regulation depends largely on the implementation of this principle as it is not possible, without accurate data, to scrutinize the activity of the healthcare providers. The existence of an appropriate and modern regulatory system is thus an instrumental factor for the global improvement of the healthcare system and, consequently, of the population’s health outcomes.

A crucial aspect of the sunshine regulation is the comparative benchmarking analysis between the healthcare providers. We quote as an example the star rating promoted by the British Care Quality Commission and by the Portuguese Regulatory Authority of Health. The star rating is an example of hierarchisation of relative quality that, according to the principle of public accountability, provides simple and objective information to society (generally in four different levels of hierarchy) on the global performance level of the organization.

In England the rating system was initially promoted by the Health Care Commission, now transformed into Care Quality Commission, and was based in performance indicators giving star ratings to NHS hospital trusts [11]. A wide range of indicators was selected including waiting times for general practitioner referral to first outpatient appointments, vacancies in medical staffing and the percentage of patients waiting on trolleys for more than 4 h. The indicators are related to a specific set of key targets designed to reflect a wide range of performance issues, following consultation with the service and other stakeholders. The overall performance rating of an NHS trust is made up of a number of performance indicators that show how trusts are doing in relation to some of the main targets set by Government for the NHS as well as other broader measures of performance.

Both the lists of indicators as well as the technical specifications used to calculate them are published in advance on the website. In short the NHS performance ratings system places trusts in England in one of four categories: 0 stars (poor quality), 1 star (adequate quality), 2 stars (good quality) and 3 stars (excellent quality). To ensure that evidence is consistently interpreted a set of guidelines—called key lines of regulatory assessment (KLORA)—are used. As stated at the website of the Care Quality Commission (www.cqc.org.uk) “we apply these guidelines to help us form a judgement about how well your service is meeting each of the outcome groups in the national minimum standards. Our primary concern is to assess the quality of outcomes that people who use your service experience. Once we have used KLORA to reach a judgement about each outcome area of the national minimum standards, we apply a set of rules to calculate the overall quality rating for your service”. It should be emphasised that in Britain commissioners are also subjected to some sort of rating, via World Class Commissioning.

More recently the system has evolved and trusts are assessed in three different dimensions: (a) core standards: standards concerned with safety and cleanliness, safeguarding children, infection control, dignity and respect, and privacy and confidentiality; (b) existing commitments: indicators concerned with waiting times for inpatient and outpatient treatment, and ambulance response times; and (c) national priorities: indicators concerned with patient reported experience of services, infection rates, waiting times for cancer treatment, and a range of public health measures. Also, other trusts, such as primary care and mental health trusts, have also received full star ratings. In 2008/2009 all 392 NHS trusts in England were given an annual rating. These can broadly be broken down into five different types of trust, as follows: (a) 169 acute and specialist trusts; (b) 152 primary care trusts; (c) 57 mental health trusts; (d) 11 ambulance trusts; and (e) 3 learning disability and other trusts.

A major issue to be considered, however, is to examine the evolution of the performance indicators over time. This evaluation unequivocally is the outcome of the sunshine regulatory method adopted. In Table 2 the performance indicators scores of the English star rating are presented and a significant evolution of the overall quality scores can be observed. It implies also a significant performance improvement. Therefore, it is reasonable to suggest that, at least in part, sunshine regulation did play an important role in this evolution.

Similarly, in Portugal the National System of Health Evaluation intends to guarantee appropriate quality standards of the healthcare services through the benchmarking of a set of quality indicators that will subsequently lead to the relative grading of the healthcare providers. The subsequent social pressure, based on the analysis of this data, makes it possible to reduce the information asymmetry as well as to improve the consumer sovereignty indicators, which for different sorts of reasons are deeply reduced in the healthcare sector. As in England the determination of the performance indicators is essential for the proper application of public accountability and for an efficient regulation of these activities.

The English experience is very important because in Portugal the Regulatory Authority of Health has the intention of applying this model (following the UK example). It is expected that the National System of Health Evaluation will be applied in 2011 and different regulatory strategies in the healthcare sector will be reinterpreted according to this perspective of sunshine regulation. In this manner, the sunshine regulation fulfils a double objective. In areas of general economic interest it offers an effective economic regulation by stimulating healthy competition in the quasi market of healthcare and, on the other hand, it delivers an appreciable social regulation by providing the public with simplified, clear and objective knowledge on the quality of the healthcare services.

Conclusion

The healthcare systems of the industrialised countries are confronted with important challenges due to the rise in healthcare costs and the subsequent lack of financial sustainability [19]. The convergence of various factors, specially, the demographic transition, will create the need for considerable creativity to overcome the inevitable economic pressures that the social protection systems will encounter. The introduction of quasi markets in healthcare is the reflection of this evolution [14] and this reformist course should be properly supervised in order to protect important social values. An example of this transformation is the creation of Foundation Trusts (not-for-profit, public benefit corporations) that have closer community links and are therefore more distanced from Government than other NHS bodies [28]. That is, management models are to be found that will not only incorporate the market rules [22] but also allow the implementation of principles and values protected in the modern societies such as accountability or responsiveness in accordance with communities’ interests.

In this manner, sunshine regulation takes on a special relevance as, by promoting publicity of the performance indicators and of the decision-making processes, it contributes directly and indirectly for an overall improvement of the healthcare system. Indeed, sunshine regulation contributes to the achievement of high levels of transparency, which are fundamental to overcome some of the market failures that are inevitable in the transformation of a vertical and integrated public system, in a decentralised network where entrepreneurialism appears to be the predominant culture.

References

Ayres, I., & Braithwaite, J. (1992). Responsive regulation. Transcending the deregulation debate. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Baldwin, R., & Cave, M. (1999). Understanding regulation. Theory, strategy and practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Boyer, R., & Saillard, Y. (2002). Regulation theory. The state of the art. London: Routledge.

Boyne, G., Farrell, C., Law, J., Powell, M., & Walker, M. (2003). Evaluating public management reforms. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Care Quality Commission: NHS performance ratings (2008/2009). An overview of the performance of NHS trusts in England, October, 2009, http://www.cqc.org.uk/.

Crew, M. (1999). Regulation under increasing competition. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Daniels, N., & Sabin, J. (1997). Limits to health care: Fair procedures, democratic deliberation, and the legitimacy problem of insurers. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 26(4), 303–350.

Daniels, N., & Sabin, J. (1998). The ethics of accountability in managed care reform. Health Affairs, 17(5), 50–65.

Daniels, N., & Sabin, J. (2002). Setting limits fairly. New York: Oxford University Press.

Daniels, N., Light, D., & Caplan, R. (1996). Benchmarks of fairness for health care reform. New York: Oxford University Press.

Harris, C. (2001). England introduces star rating system for hospital trusts. British Medical Journal, 323(7315), 709.

Khaleghian, P., & Gupta, M. (2005). Public management and the essential public health functions. World Development, 33(7), 1083–1099.

Kon, J. (2003). Understanding regulation and compliance. London: Securities Institute Services.

Laugesen, M. (2005). Why some market reforms lack legitimacy in health care. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 30(6), 1065–1100.

Majone, G. (1994). The rise of the regulatory state in Europe. West European Politics, 17(3), 77–101.

Majone, G. (1997). From the positive to the regulatory state. Journal of Public Policy, 17(2), 139–167.

Nunes, R., Rego, G., Brandão, C. (2007). The rise of independent regulation in health care. Health Care Analysis, 15(3), 169–177.

Nunes, R., Rego, G., & Brandão, C. (2009). Healthcare regulation as a tool for public accountability. Medicine, Healthcare and Philosophy, 12, 257–264.

OECD. (2006). Future budget pressures arising from spending on health and long-term care. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Rawls, J. (1971). A theory of justice. New York: Harvard University Press.

Rawls, J. (2001). Justice as fairness. In E. Kelly (Ed.), A restatement. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Rechel, B., Wright, S., Edwards, N., Dowdeswell, B., & McKee, M. (2009). Investing in hospitals of the future. Observatory studies No. 16, European observatory on health systems and policies. Copenhagen.

Saltman, R., & Busse, R. (2002). Balancing regulation and entrepreneurialism in Europe’s health sector: Theory and practice. In R. Saltman, R. Busse, & E. Mossialos (Eds.), European observatory on health care systems, regulating entrepreneurial behaviour in European health care systems. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Selznick, P. (1985). Focusing organisational research on regulation. In R. Noll (Ed.), Regulatory policy and the social sciences. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Walshe, K. (2002). The rise of regulation in the NHS. British Medical Journal, 324, 967–970.

Walshe, K. (2003). Regulating healthcare. A prescription for improvement? State of Health Series, Open University Press, Maidenhead.

Whincop, M. (2001). Bridging the entrepreneurial financial gap. Linking governance with regulatory policy. Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Wilmot, S. (2004). Foundation trusts and the problem of legitimacy. Health Care Analysis, 12(2), 157–169.

Daniels, Ref. 5 above.

Walshe, Ref. 3 above.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Nunes, R., Brandão, C. & Rego, G. Public Accountability and Sunshine Healthcare Regulation. Health Care Anal 19, 352–364 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10728-010-0156-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10728-010-0156-6