Abstract

This study investigates the link between the educational characteristics of partners in heterosexual relationships and their transition to second births, accounting for the selection into parenthood by fitting multi-level event history models. We compare the fertility of Beckerian unions characterized by gender-role specialization with the fertility of dual-earner couples, characterized by the pooling of incomes. Focusing on the economic aspect of the educational degree, in a first step, we estimate the earning potential and unemployment risks by field and level of education, country and sex using European Labour Force Surveys. Next, we link these results with Generation and Gender Survey data from six countries and model couples’ transition to second births. We find evidence in support of both the pooling of resources family model (notably in Belgium) and the Beckerian gender-role specialization model. The effects of the earning potential and unemployment risk attached to his and her field of education tends to vary by country context.

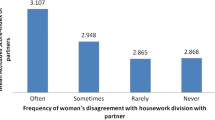

Source: Own calculations on EU-LFS data 2009–2013

Source: Own calculations on EU-LFS data 2009–2013

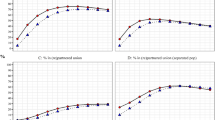

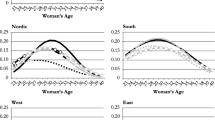

Source: Own calculations on EU-LFS data 2003–2013

Source: Own calculations on EU-LFS data 2003–2013

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.Notes

We excluded France because categories of education, health and welfare and services were not included, harming the comparability of results. We also had to exclude Norway because it was not possible to estimate the earning potential by means of the European Labour Force Surveys, given that the income variable for this country was not available.

http://www.uis.unesco.org/Education/Pages/international-standard-classiication-of-education.aspx accessed on the 14 September 2015.

This database is an administrative data collection that is administered jointly by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization Institute for Statistics (UNESCO-UIS), the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the Statistical Office of the European Union (EUROSTAT).

Since Eurostat does not provide information on the general/unspecified field of study, we calculated the proportion of women in this category using GGS data themselves, considering all men and women born between 1960 and 1987 with at least upper-secondary degree.

Control variables for the transition to the second birth include duration splines, woman’s age at the first birth and its square, union’s cohorts, respondent’s sex, respondent’s enrolment, union order of the respondent, type of union, age difference between partners.

References

Becker, G. S. (1964). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Becker, G. S. (1991). A treatise on the family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Begall, K. (2013). How do educational and occupational resources relate to the timing of family formation? A couple analysis of the Netherlands. Demographic Research,29(October), 907–936.

Begall, K., & Mills, M. C. (2013). The influence of educational field, occupation, and occupational sex segregation on fertility in the Netherlands. European Sociological Review,29, 720–742.

Billari, F., & Kohler, H.-P. (2004). Patterns of low and lowest-low fertility in Europe. Population Studies,58(2), 161–176.

Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2016). The gender wage gap: Extent, trends, and explanations. IZA Discussion Paper Series, no. 9656.

Charles, M., & Bradley, K. (2009). Indulging our gendered selves? Sex segregation by field of study in 44 countries. American Journal of Sociology,114(4), 924–976.

Corijn, M., Liefbroer, A., & de Gierveld, J. (1996). It takes two to tango, doesn’t it? The influence of couple characteristics on the timing of the birth of the first child. Journal of Marriage and the Family,58(1), 117–126.

De Hauw, Y., Grow, A., & Van Bavel, J. (2017). The reversed gender gap in education and assortative mating in Europe. European Journal of Population, 33(4), 445–474.

DiPrete, T. A., & Buchmann, C. (2006). Gender-specific trends in the value of education and the emerging gender gap in college completion. Demography, 43(1), 1–24.

Dribe, M., & Stanfors, M. (2010). Family life in power couples: Continued childbearing and union stability among the educational elite in Sweden, 1991–2005. Demographic Research,23, 847–878.

Esping-Andersen, G., & Billari, F. C. (2015). Re-theorizing family demographics. Population and Development Review,41(1), 1–51.

Esteve, A., García-Román, J., & Permanyer, I. (2012). The gender-gap reversal in education and its effect on union formation: The end of hypergamy? Population and Development Review,38, 535–546.

Frejka, T. (2008). Overview Chapter 2: Parity distribution and completed family size in Europe. Demographic Research,19(July), 139–170.

Goldscheider, F., Bernhardt, E., & Lappegård, T. (2015). The gender revolution: A framework for understanding changing family and demographic behaviour. Population and Development Review,41(2), 207–239.

Grow, A., & Van Bavel, J. (2015). Assortative mating and the reversal of gender inequality in education in Europe—An agent-based model. PLoS ONE,10(6), e01.

Gustafsson, S., & Worku, S. (2006). Assortative mating by education and postponement of couple formation and first birth in Britain and Sweden. In S. Gustafsson, & A. Kalwij (Eds.), Education and postponement of maternity. Economic analysis for industrialized countries (pp. 259–284). Dordrecht: Springer.

Harkonen, J., & Dronkers, J. (2006). Stability and change in the educational gradient of divorce. A comparison of seventeen countries. European Sociological Review,22(5), 501–517.

Hobcraft, J., & Kiernan, K. (1995). Becoming a parent in Europe: Discussion Paper WSP/116, Welfare State Programme. London: The Toyota Centre London School of Economics.

Hoem, J. M., Neyer, G., & Andersson, G. (2006a). Education and childlessness. Demographic Research,14(May), 331–380.

Hoem, J. M., Neyer, G., & Andersson, G. (2006b). Educational attainment and ultimate fertility among Swedish Women Born in 1955–59. Demographic Research,14, 381–404.

Huinink, J., & Kohli, M. (2014). A life-course approach to fertility. Demographic Research, 30, 1293–1326.

Jalovaara, M., & Miettinen, A. (2013). Does his paycheck also matter? Demographic Research,28(April), 881–916.

Kalmijn, M. (2003). Union disruption in the Netherlands: Opposing influences of task specialization and assortative mating? International Journal of Sociology,33(2), 36–64.

Klesment, M., & Van Bavel, J. (2017). The reversal of the gender gap in education, motherhood, and women as main earners in Europe. European Sociological Review, 33(3), 465–481.

Klesment, M., Puur, A., Rahnu, L., & Sakkeus, L. (2014). Varying association between education and second births in Europe: Comparative analysis based on the EU-SILC data. Demographic Research,31(1), 813–860.

Kravdal, Ø. (2001). The high fertility of college educated women in Norway. Demographic Research,5(December), 187–216.

Kravdal, Ø. (2007). Effects of current education on second- and third-birth rates among Norwegian women and men born in 1964: Substantive interpretations and methodological issues. Demographic Research,17(November), 211–246.

Kravdal, O., & Rindfuss, R. R. (2008). Changing relationships between education and fertility: A study of women and men born 1940 to 1964. American Sociological Review,73(5), 854–873.

Kreyenfeld, M. (2002). Time squeeze, partner effect or self-selection? Demographic Research,7(July), 15–48.

Lappegård, T., & Rønsen, M. (2005). The multifaceted impact of education on entry into motherhood. European Journal of Population,21(1), 31–49.

Lappegard, T., Ronsen, M., & Skrede, K. (2011). Fatherhood and fertility. Fathering,9(1), 103–120.

Lillard, L. A., & Panis, C. W. A. (2003). aML: Multilevel multiprocess statistical software, version 2.0. Los Angeles, CA: EconWare.

Mäenpää, E., & Jalovaara, M. (2014). Homogamy in socio-economic background and education, and the dissolution of cohabiting unions. Demographic Research,30(June), 1769–1792.

Martín-García, T. (2009). ‘Bring men back in’: A re-examination of the impact of type of education and educational enrolment on first births in Spain. European Sociological Review,25(2), 199–213.

Martín-García, T., & Baizán, P. (2006). The impact of the type of education and of educational enrolment on first births. European Sociological Review,22(3), 259–275.

Matysiak, A., Sobotka, T., & Vignoli, D. (2018). The Great Recession and fertility in Europe: A sub-national analysis. Vienna Institute of Demography Working Papers VID WP 02/2018.

Matysiak, A., Styrc, M., & Vignoli, D. (2014). The educational gradient in marital disruption: A meta-analysis of European research findings. Population Studies,68(2), 197–215.

Matysiak, A., & Węziak-Białowolska, D. (2016). Country-specific conditions for work and family reconciliation: An attempt at quantification. European Journal of Population,32(4), 475–510.

McDonald, P. (2000). Gender equity in theories of fertility transition. Population and Development Review, 26(3), 427–439.

Nitsche, N., Matysiak, A., Van Bavel, J., & Vignoli, D. (2018). Partners’ educational pairings and fertility across Europe. Demography,38, 1–36.

Oppenheimer, V. (1988). A theory of marriage timing. American Journal of Sociology,94(3), 563–591.

Oppenheimer, V. (1994). Women’s rising employment and the future of the family in industrial societies. Population and Development Review,20(2), 293–342.

Osiewalska, B. (2017). Childlessness and fertility by couples’ educational gender (in)equality in Austria, Bulgaria, and France. Demographic Research,37(August), 325–362.

Puur, A., Oláh, L. S., Tazi-Preve, M. I., & Dorbritz, J. (2008). Men’s childbearing desires and views of the male role in Europe at the dawn of the 21st century. Demographic Research, 19, 1883–1912.

Reimer, D., Noelke, C., & Kucel, A. (2008). Labour market effects of field of study in comparative perspective: An analysis of 22 European countries. International Journal of Comparative Sociology,49(4–5), 233–256.

Schwartz, C. R., & Han, H. (2014). The reversal of the gender gap in education and trends in marital dissolution. American Sociological Review, 79(4), 605–629.

Singley, S. G., & Hynes, K. (2005). Transitions to parenthood: Work-family policies, gender, and the couple context. Gender & Society,19(3), 376–397.

Sobotka, T., & Beaujouan, E. (2014). Two is best? The persistence of a two-child family ideal in Europe. Population and Development Review, 40(3), 391–419.

Tesching, K. (2012). Education and fertility. Dynamic interrelations between women’s educational level, educational field and fertility in Sweden. Stockholm University Demography Unit—Dissertation Series, No 6.

Testa, M., Cavalli, L., & Rosina, A. (2014). The effect of couple disagreement about child-timing intentions: A parity-specific approach. Population and Development Review,40(March), 31–53.

Theunis, L., Schnor, C., Willaert, D., & Van Bavel, J. (2018). His and her education and marital dissolution: Adding a contextual dimension. European Journal of Population,34(4), 663–687.

Trimarchi, A., & Van Bavel, J. (2017). Education and the transition to fatherhood: The role of selection into union. Demography,54(1), 1–42.

Trimarchi, A., & Van Bavel, J. (2018). Pathways to marital and non-marital first birth: The role of his and her education. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research,2017(15), 143–179.

Van Bavel, J. (2010). Choice of study discipline and the postponement of motherhood in Europe: The impact of expected earnings, gender composition, and family attitudes. Demography,47(2), 439–458.

Van Bavel, J. (2012). The reversal of gender inequality in education, union formation and fertility in Europe. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research,10, 127–154.

Van Bavel, J., & Rózańska-Putek, J. (2010). Second birth rates across Europe: Interactions between women’s level of education and child care enrolment. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 8(1), 107–138.

Van de Werfhorst, H. G. (2001). Field of study and social inequality. Four types of educational resources in the process of stratification in the Netherlands. Catholic University of Nijmegen.

Vignoli, D., Drefahl, S., & De Santis, G. (2012). Whose job instability affects the likelihood of becoming a parent in Italy? A tale of two partners. Demographic Research,26(January), 41–62.

Xie, Y., Raymo, J. M., Goyette, K., & Thornton, A. (2003). Economic potential and entry into marriage and cohabitation. Demography,40(2), 351–367.

Zeman, K., Beaujouan, É., Brzozowska, Z., & Sobotka, T. (2018). Cohort fertility decline in low fertility countries: Decomposition using parity progression ratios. Demographic Research,38(1), 651–690.

Funding

This study was funded by the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP/2007-2013)/ERC Grant Agreement No. 312290 for the GENDERBALL project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Trimarchi, A., Van Bavel, J. Partners’ Educational Characteristics and Fertility: Disentangling the Effects of Earning Potential and Unemployment Risk on Second Births. Eur J Population 36, 439–464 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-019-09537-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-019-09537-w