Abstract

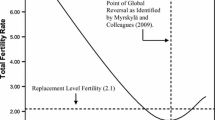

This article has two objectives. First, it aims to complement and extend existing research on post-socialist demographic change, which has thus far tended to focus on Central and Eastern Europe. It does this by describing the nature of post-Soviet trends in nuptiality and fertility in Tajikistan, the republic with the highest rate of population growth during the Soviet period. It finds evidence for a decrease in period fertility after independence: initially, through a decline at higher orders; then, through a significant decrease in the rate of first births, associated with a dramatic decrease in the rate of first union formation since the mid-1990s. Second, it aims to contribute to the demography of conflict and of food crisis. Most clearly, it finds strong evidence for a decrease in nuptiality and fertility associated with the 1995 food crisis.

Résumé

Cet article a deux objectifs. Premièrement, il contribue à enrichir et élargir les recherches relatives aux changements démographiques observés au cours de la période post-socialiste, focalisées jusqu’à présent sur l’Europe Centrale et Orientale, en décrivant les caractéristiques des évolutions post-soviétiques de la nuptialité et de la fécondité au Tadjikistan, République ayant eu le taux de croissance de la population le plus élevé au cours de la période soviétique. Après l’indépendance, le déclin de la fécondité transversale a d’abord débuté par une baisse des naissances de rangs élevés, puis a continué avec une baisse du taux des naissances de premier rang associée à une chute dramatique du taux de formation de la première union depuis le milieu des années 1990. Deuxièmement, cet article apporte une contribution à la démographie des conflits et des crises alimentaires. Plus précisément, il montre clairement une association entre le déclin de la nuptialité et de la fécondité et la crise alimentaire de 1995.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.Notes

However, note that the Baltic republics of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania experienced less severe and prolonged decreases in GDP per capita than, for example, Moldova and Ukraine.

There is historical precedent for the 1995 food crisis in Tajikistan. As Harris describes (Harris 2006, p. 26), in the early part of the twentieth century, just as in the Soviet period, the population in what is now Tajikistan was reliant on grain imports after the Tsarist government persuaded local farmers to plant cotton rather than grain. Just as in 1995, these imports were then disrupted—in this case during WW1 when the train lines were cut, stopping grain arriving from the north. In the absence of any international aid, there was a serious famine, estimated to have killed almost a million people (Etherton 1925, p. 154).

The head of the International Federation of Red Cross’ mission in 2001 reported that ‘people have already sold parts of their homes including doors and windows. They now have nothing left to sell… We have seen children digging among rat holes in wheat fields, searching for grain hoarded by the rodents for the winter’ (IRINCAS 2001).

Many religious wedding ceremonies (nikoh) in Tajikistan are not officially registered (Dikaev 2005). Therefore, in the MICS survey, women were asked the question ‘In what month and year did you first marry or start living with a man as if married?’ This is a more accurate reflection of the date of union than the date of marriage registration and, given the significant under-registration issues, a more complete one. Throughout this article, the terms ‘rate of first marriage’ and ‘rate of first union formation’ are used interchangeably; both refer to measures calculated on answers to this question.

Truncation is less of an issue for trends in first unions and first births, which are concentrated at a relatively young age in Tajikistan: traditionally an unmarried woman over the age of 20 is in danger of being considered an ‘old maid’ (Tabyshalieva 1997, p. 52). Therefore, these rates are calculated based on events and exposure for women aged 15–29 years inclusive, for 1986 onwards.

See Rodríguez (2007) for a helpful introduction to proportional hazard models.

The baseline hazards of all models were chosen with two considerations in mind: first, to adequately control for compositional changes in the population at risk over time; second, to ensure a parsimonious model with reasonably few parameters. The baseline hazards in the paper reflect a balance between these two criteria, such that further increasing the number of categories for the baseline hazard does not alter the period coefficients.

In the models here, modelling the hazard of a birth at a given process time t is preferred to shifting back the date of birth by 9 months and modelling the hazard of conception. Focusing only on conceptions does not account for any period effects on fertility acting, for example, through changes in the rate of spontaneous abortions. Ideally, one would use a series of models to estimate separately period effects on conceptions within union, and on spontaneous abortion after conception, but these data are not available.

In the MICS survey, the month but not the date of first union was recorded. In calculating exposure time between date of first union and date of first birth, unions were assumed to take place on the 15th of the month. In total, 332 first births (8% of the total of 4,245 between 1986 and 2004 in the sample) were excluded: 15 first births to women who had never been in first union, and 317 births with an estimated conception date before marriage.

Since there are very few higher-order births to women outside of union in Tajikistan (an estimated 3.5% of second births in the TLSS survey, and less than 1% of births at orders three or above), we present models for overall parity-specific rates and do not consider separate models specifically for those in union.

A covariate for the woman’s highest educational level was also included but, since made it no difference to the nature of the temporal trend, was not retained.

No official registration data on age-specific fertility rates for Tajikistan are available after 1995 from TransMONEE (2006), precluding calculation of the TF15–34 for direct comparison with the survey estimate.

Since annual parity-specific rates are subject to sampling variability at higher-birth orders, the rates are smoothed using a 3-year moving average.

332 first births (8% of the total in the sample) were estimated to have been conceived before marriage (see footnote 9).

Higher-order births are pooled together in this model to increase the power of tests for differences in fertility between annual periods.

This, and subsequent, p values from model estimates are results of Wald tests assessing the significance of a calendar year coefficient at the 5% level, compared with a reference comparison year. Standard errors were adjusted to take account of the surveys’ sample design.

Across all the women in the survey to have had a first birth within marriage, almost 40% (65%) had their child within the first year (18 months) of marriage.

References

Aassve, A., Gjonca,A., & Mencarini, L. (2006). The highest fertility in Europe—for how long? Analyses of recent fertility changes in Albania. Institute for social and economic research, University of Essex. Working Paper No. 2006-56.

Agadjanian, V. (1999). Post-soviet demographic paradoxes: ethnic differences in marriage and fertility in Kazakhstan. Sociological Forum, 14(3), 425–446.

Agadjanian, V., Dommaraju, P., & Glick, J. (2008). Reproduction in upheaval: ethnicity, fertility, and societal transformations in Kazakhstan. Population Studies, 62(2), 211–233.

Agadjanian, V., & Makarova, E. (2003). From Soviet modernization to post-Soviet transformation: understanding marriage and fertility dynamics in Uzbekistan. Development and Change, 34(3), 447–473.

Agadjanian, V., & Prata, N. (2002). War, peace and fertility in Angola. Demography, 39(2), 215–231.

Anderson, B. A., & Silver, B. D. (1989). Demographic sources of the changing ethnic composition of the Soviet Union. Population and Development Review, 15(4), 609–656.

Anichkin, A. B., & Vishnevskii, A. G. (1992). 3 types of birthrates in the USSR—stages of demographic transition. Matekon, 28(4), 61–74.

Anichkin, A. B., & Vishnevskii, A. G. (1994). Three types of fertility behavior in the USSR. In W. Lutz, S. Scherbov, & A. Volkov (Eds.), Demographic trends and patterns in the Soviet Union before 1991 (pp. 61–74). London: Routledge.

Atkin, M. (1997). Tajikistan’s civil war. Current History, 96(612), 336–340.

Atkinson, A. B., & Micklewright, J. (1992). Economic transformation in Eastern Europe and the distribution of income. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Babu, S., & Reidhead, W. (2000). Poverty, food security, and nutrition in Central Asia: A case study of the Kyrgyz Republic. Food Policy, 25, 647–660.

Becker, C., & Hemley, D. D. (1998). Demographic change in the former Soviet Union during the transition period. World Development, 26(11), 1957–1975.

Bengtsson, T., & Dribe, M. (2006). Deliberate control in a natural fertility population: southern Sweden, 1766–1864. Demography, 43(4), 727–746.

Bongaarts, J. (1980). Does malnutrition affect fecundity? A summary of evidence. Science, 208(4444), 564–569.

Brown, B. A. (1998). The civil war in Tajikistan, 1992–1993. In M.-R. Djalili, F. Grare, & S. Akiner (Eds.), Tajikistan: The trials of independence (pp. 86–96). London: Curzon.

Bulgaru, M., Bulgaru, O., Sobotka, T., & Zeman, K. (2000). Past and present population development in the Republic of Moldova. In T. Kučera, O. Kučerová, O. Opara, & E. Schaich (Eds.), New demographic faces of Europe: The changing population dynamics in countries of Central and Eastern Europe (pp. 221–246). Berlin: Springer.

Cai, Y., & Feng, W. (2005). Famine, social disruption, and involuntary fetal loss. Demography, 42, 301–322.

Conrad, C., Lechner, M., & Werner, W. (1996). East German fertility after unification: crisis or adaptation? Population and Development Review, 22(2), 331–358.

De Soto, H., Gordon, P., & Saidov, F. (2001). Voices of the Poor from Tajikistan: A Qualitative Assessment of Poverty for the Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP). Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Dikaev, T. (2005). Tajikistan’s unrecorded lives. Reporting Central Asia 391.

Dommaraju, P., & Agadjanian, V. (2008). Nuptiality in Soviet and post-Soviet Central Asia. Asian Population Studies, 4(2), 195–213.

Duncan, J. (2000). Agricultural Land Reform and Farm Reorganization in Tajikistan. RDI Reports on Foreign Aid and Development, No. 106, Rural Development Institute.

Dyson, T. (1991a). On the demography of South Asian famines: Part 1. Population Studies, 45, 5–25.

Dyson, T. (1991b). On the demography of South Asian famines: Part II. Population Studies, 45, 279–297.

Economist Intelligence Unit. (1994). Tajikistan. The Economist Intelligence Unit, Country Report (4th quarter).

Economist Intelligence Unit. (1995a). Tajikistan. The Economist Intelligence Unit, Country Report (1st quarter).

Economist Intelligence Unit. (1995b). Tajikistan. The Economist Intelligence Unit, Country Report (3rd quarter).

Economist Intelligence Unit. (1996). Tajikistan. The Economist Intelligence Unit, Country Report (2nd quarter).

Economist Intelligence Unit. (1997). Tajikistan. The Economist Intelligence Unit, Country Report (4th quarter).

Economist Intelligence Unit. (1998). Tajikistan. The Economist Intelligence Unit, Country Report (2nd quarter).

Economist Intelligence Unit. (2001a). Tajikistan. The Economist Intelligence Unit, Country Report (October).

Economist Intelligence Unit. (2001b). Tajikistan. The Economist Intelligence Unit, Country Report (April).

Etherton, P. T. (1925). In the heart of Asia. London: Constable and Co. (cited in Harris 2006).

Falkingham, J. (2000). Women and gender relations in Tajikistan Manila. Asian Development Bank.

Falkingham, J. (2003). Inequality and changes in women’s use of maternal health-care services in Tajikistan. Studies in Family Planning, 34(1), 32–43.

Falkingham, J. (2005). The end of the rollercoaster? Growth, inequality and poverty in Central Asia and the Caucasus. Social Policy and Administration, 39(4), 340–360.

Falkingham, J., Klugman, J., Marnie, S., & Micklewright, J. (1997). Household welfare in Central Asia: An introduction to the issues. In J. Falkingham, J. Klugman, S. Marnie, & J. Micklewright (Eds.), Household welfare in Central Asia (pp. 1–18). Basingstoke: Macmillan.

FAO/WFP. (2001). Special Report FAO/WFP Crop and Food Supply Assessment Mission to Tajikistan 7 August 2001, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Global Information and Early Warning System on Food and Agriculture, World Food Programme.

Foroughi, P. (2002). Tajikistan: Nationalism, ethnicity, conflict and socio-economic disparities—sources and solutions. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, 22(1), 39–61.

Frejka, T. (2008). Determinants of family formation and childbearing during the societal transition in Central and Eastern Europe. Demographic Research, 19, 139–170.

Galloway, P. R. (1988). Basic patterns in annual variations in fertility, nuptiality, mortality and prices in pre-industrial Europe. Population Studies, 42, 275–303.

Gentile, M. (2005). Population geography perspectives on the Central Asian republics. Institute for Futures Studies, Stockholm, Working Paper 16.

Grand, J.-M., Leather, C., & Mason, F. (2001). Tajikistan: What role for nongovernmental organizations? The Geopolitics of Hunger, 2000–2001. Action against hunger (pp. 63–77). Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Handwerker, W. P. (1988). Sampling variability in microdemographic estimation of fertility parameters. Human Biology, 60(2), 305–318.

Harris, C. (1998). Coping with daily life in post-Soviet Tajikistan: The Gharmi villages of Khatlon province. Central Asian Survey, 17(4), 655–672.

Harris, C. (1999). Health education for women as a liberatory process? An example from Tajikistan. In H. Afshar & S. Barrientos (Eds.), Women, globalization and fragmentation in the developing world (pp. 196–214). London: MacMillan.

Harris, C. (2002). Muslim views on population: the case of Tajikistan. In J. Meuleman (Ed.), Islam in the era of globalization: Muslim attitudes towards modernity and identity (pp. 211–225). London: Routledge.

Harris, C. (2004). Control and subversion: Gender relations in Tajikistan. London: Pluto.

Harris, C. (2006). Muslim youth: Tensions and transitions in Tajikistan. Oxford: Westview Press.

Hionidou, V. (2002). ‘Send us either food or coffins’: The 1941–2 famine on the Aegean island of Syros. In T. Dyson & C. Ó. Gráda (Eds.), Famine demography: Perspectives from the past and present (pp. 181–203). New York: Oxford University Press.

Howell, J. (1996). Coping with transition: insights from Kyrgyzstan. Third World Quarterly, 17(1), 53–68.

International Crisis Group. (2001). Tajikistan: an uncertain peace. Osh, Kyrgyzstan/Brussels: International Crisis Group.

IRINCAS. (2001). Central Asia Weekly Round-up 21: 24–30 August 2001, United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs: Integrated Regional Information Network for Central Asia (IRINCAS).

Jones, E., & Grupp, F. W. (1987). Modernisation, value change and fertility in the Soviet Union. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kaser, M. (1997). Economic transition in six Central Asian economies. Central Asian Survey, 16(1), 5–26.

Katus, K., Sakkeus, L., Puur, A., & Põldma, A. (2000). Demographic development of Estonian population: Recent changes in the context of the long-term trends. In T. Kučera, O. Kučerová, O. Opara, & E. Schaich (Eds.), New demographic faces of Europe (pp. 125–140). Berlin: Springer.

Khlat, M., Deeb, M., & Courbage, Y. (1997). Fertility levels and differentials in Beirut during wartime: An indirect estimation based on maternity registers. Population Studies, 51(1), 85–92.

Kohler, H.-P., & Kohler, I. (2002). Fertility decline in Russia in the early and mid 1990s: The role of economic uncertainty and labour market crises. European Journal of Population, 18, 233–262.

Kotowska, I., Józwiak, J., Matysiak, A., & Baranowska, A. (2008). Poland: Fertility decline as a response to profound societal and labour market changes? Demographic Research, 19, 795–854.

Kučera, T., Kučerová, O., Opara, O., & Schaich, E. (2000). New demographic faces of Europe: the changing population dynamics in countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Berlin: Springer.

Lindstrom, D. P., & Berhanu, B. (1999). The impact of war, famine and economic decline on marital fertility in Ethiopia. Demography, 36(2), 247–261.

Lutz, W., & Scherbov, S. (1994). Survey of fertility trends in the republics of the Soviet Union: 1959–1990. In W. Lutz, S. Scherbov, & A. Volkov (Eds.), Demographic trends and patterns in the Soviet Union before 1991 (pp. 19–40). London: Routledge.

Lynch, D. (2002). Separatist states and post-Soviet conflicts. International Affairs, 78(4), 831–848.

Macura, M. (2000). Fertility decline in the transition economies, 1989–1998: economic and social factors revisited. United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) Economic Survey of Europe, 1, 189–207.

Menken, J., Trussell, J., & Watkins, S. (1981). The nutrition fertility link: An evaluation of the evidence. Journal of Interdisciplinary History, XI(3), 425–441.

OCHA. (2000). Tajikistan-drought OCHA situation report No. 2, United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA).

Olimova, S., & Bosc, I. (2003). Labour migration from Tajikistan. Dushanbe: International Organisation for Migration.

Palloni, A., Hill, K., & Aguirre, G. P. (1996). Economic swings and demographic changes in the history of Latin America. Population Studies, 50, 105–132.

Pebley, A. R., Huffman, S. L., Chowdhury, A., & Stupp, P. W. (1985). Intra-uterine mortality and maternal nutritional status in rural Bangladesh. Population Studies, 39(3), 425–440.

Perelli-Harris, B. (2005). The path to lowest-low fertility in Ukraine. Population Studies, 59(1), 55–70.

Philipov, D., & Dorbritz, J. (2003). Demographic consequences of economic transition in countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

Ren, R. (2004). Appendix B: Estimates of sampling errors (pp. 231–233). Uzbekistan Health Examination Survey 2002. Calverton, Maryland., Analytical and Information Center, Ministry of Health of the Republic of Uzbekistan [Uzbekistan], State Department of Statistics, Ministry of Macroeconomics and Statistics [Uzbekistan], and ORC Macro.

Rodríguez, G. (2007). Lecture notes on generalized linear models (Chapter 7). Retrieved September 2008, from http://data.princeton.edu/wws509/notes/.

Rowland, R. H. (2005). National and regional population trends in Tajikistan: Results from the recent census. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 46(3), 202–223.

Shakhotska, L. P. (2000). Demographic development of the Republic Belarus. In T. Kučera, O. Kučerová, O. Opara, & E. Schaich (Eds.), New demographic faces of Europe (pp. 29–51). Berlin: Springer.

Sillanpää, A. (2002). The effects of wars on population. In A. Reader, I. Taipale, P. H. Mäkelä, K. Juva, et al. (Eds.), War or Health? (pp. 198–207). Cape Town: NAE.

Sobotka, T. (2002). Ten years of rapid fertility changes in the European post-communist countries. Population Research Centre Working Paper Series 02-01.

Sobotka, T. (2004). Postponement of childbearing and low fertility in Europe. Amsterdam: Dutch University Press.

Sobotka, T., Št’astná, A., Zeman, K., Hamplová, D., & Kantorová, V. (2008). Czech Republic: A rapid transformation of fertility and family behaviour after the collapse of state socialism. Demographic Research, 19, 403–454.

Standing, G. (1996). Social protection in Eastern and Central Europe: a tale of slipping anchors and torn safety nets. In G. Esping-Andersen (Ed.), Welfare states in transition: National adaptations in global economics (pp. 225–255). London: Sage.

Stankuniene, V. (2000). Recent population development in Lithuania. In T. Kučera, O. Kučerová, O. Opara, & E. Schaich (Eds.), New demographic faces of Europe: the changing population dynamics in countries of Central and Eastern Europe (pp. 199–220). Berlin: Springer.

Stein, Z., & Susser, M. (1975). Fertility, fecundity, famine: Food rations in the Dutch famine 1944/5 have a causal relation to fertility, and probably to fecundity. Human Biology, 47(1), 131–154.

Steshenko, V. (2000). Demographic situation in Ukraine in the transition period. In T. Kučera, O. Kučerová, O. Opara, & E. Schaich (Eds.), New demographic faces of Europe: The changing population dynamics in countries of Central and Eastern Europe (pp. 347–367). Berlin: Springer.

Tabyshalieva, A. (1997). Women of Central Asia and the fertility cult. Anthropology and Archeology of Eurasia, 36(2), 45–62.

Tajikistan State Committee on Statistics. (2001). Population of Tajikistan, according to the census 20–27 January 2000. Dushanbe.

Tett, G. (1996). Ambiguous alliances: Marriage and identity in a Muslim village in Soviet Tajikistan, PhD dissertation, University of Cambridge.

Thornton, A., & Philipov, D. (2009). Sweeping changes in marriage, cohabitation and childbearing in Central and Eastern Europe: New Insights from the developmental idealism framework. European Journal of Population, 25, 123–156.

TransMONEE. (2006). TransMONEE 2006 Database. Florence: Unicef Innocenti Research Centre.

Turner, R. (1993). Tajiks have the highest fertility rates in newly independent Central Asia. Family Planning Perspectives, 25(3), 141–142.

United Nations Development Programme. (2000). Tajikistan: Human Development Report 2000, United Nations Development Programme.

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. (2000). Fertility decline in the transition economies, 1989–1998: Economic and social factors revisited (pp. 189–207). Economic Survey of Europe, 2000, Geneva.

Westoff, C. F. (2005). Recent Trends in Abortion and Contraception in 12 Countries. DHS Analytical Studies No.8. Calverton, MD: ORC Macro.

World Food Programme. (1996). Addendum—country strategy outline—Tajikistan. WFP/EB.3/96/6/Add.5, World Food Programme.

World Food Programme. (2001). WFP Emergency Report No. 7, World Food Programme.

World Food Programme. (2003). Protracted relief and recovery operation—Tajikistan 10231.0. WFP/EB.1/2003/6-A/2, World Food Programme.

Zakharov, S. (2008). Russian Federation: From the first to second demographic transition. Demographic Research, 19, 907–972.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Chris Wilson and Tom King who provided helpful suggestions on various drafts of this paper. Remaining shortcomings are the authors’ own responsibility. The support of the United Kingdom Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) (award no. PTA-030-2005-01006) is acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Clifford, D., Falkingham, J. & Hinde, A. Through Civil War, Food Crisis and Drought: Trends in Fertility and Nuptiality in Post-Soviet Tajikistan. Eur J Population 26, 325–350 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-010-9206-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-010-9206-x