Abstract

Free-surface flows with riparian corridors are known to develop large eddies resulting from the instability associated to the inflectional profile of the longitudinal velocity in the spanwise direction. They periodically generate strong momentum exchanges inside the vegetation corridor, triggering a wave-like motion, detectable as free-surface oscillations and out-of-phase velocity components. We propose a characterization of the flow inside the vegetation corridor, focusing on the wave-like motion and its influence on secondary currents. We conditionally sample the fluid motion to highlight the structure of the phase-averaged coherent structure. Quadrant analysis shows that there is a strong variation of Reynolds stress anisotropy in the spanwise direction, which is one of the key generation mechanisms of secondary currents. Spectrograms of longitudinal and lateral velocity fluctuations reveal that the oscillatory motion is imposed on the whole of the vegetated layer, because of continuity. The analysis of the phase-averaged 2D vertical-longitudinal flow reveals that there is a complex 3D pattern of mass fluxes associated to each large eddy. In particular there is an anti-symmetric net mass imbalance which, by mass conservation, generates a mass flux directed outwards, to the main channel, near the bottom of the channel. The Eulerian expression of this motion is obtained as the spatial average of the flow over the length of the large eddy, resulting in the pattern of the secondary current in the vertical-spanwise plane. It is shown that the secondary motion is a necessary feature of free-surface turbulent flows that develop large-scale inflectional instabilities.

Article highlights

-

The flow presents a marked anisotropy in the core of the large-scale eddies resulting from high shear stress associated with the passage of this, and the spanwise variation of Reynolds stress anisotropy is related to the formation and growth of secondary flow.

-

Analysis of the phase-averaged 2D vertical-longitudinal flow revealed that there is a complex 3D pattern of mass fluxes associated to large eddy, and by spatially-averaging this flow along the length of the eddy, it is obtained the Eulerian vertical-spanwise velocity field where the secondary currents are visible.

-

A deterministic model of streamlines trends is proposed, based on the continuity equation, which explains the secondary current as a function of inflectional instability.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Riverbank vegetation plays a major role in stream morphological stability and is fundamental for the balance of aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. Adopting a holistic view of a stream, it can be argued that its morphological, biological, ecological and social strata have profound links to its hydrodynamics. This justifies the considerable investment in the characterization of flows within or bounded by different types of vegetation [1,2,3]. As a contribution for this theme, in this paper, we analyze turbulent free-surface flows in channels with arrays of vertical emergent circular cylinders along the margin. The geometry of the system captures the main features of riparian zones of temperate climates [4] or of mangrove forests in river deltas [5].

If the solid fraction of the array is constant, the mean flow (time- and space-averaged flow) in the array of cylinders is determined by the balance of gravity, pressure forces and drag on the stems and bottom [6, 7]. The mean longitudinal velocity is smaller in the array relatively to the unobstructed part of the channel (henceforth, for simplification, main channel), for which, in the integral sense, flow resistance is due to bottom drag only. The spanwise distribution of the longitudinal mean velocity (time- and space-averaged) may exhibit a strong gradient and is generally similar to an unstable S-shaped curve, in the sense of Fjortoft [8]. However, the shear rate may not be continuous; If the interface between the array of stem and the main channel is sharp, a kink is visible in the laboratory results of White and Nepf [3], based on LDA velocity measurements, or Caroppi et al. [9], based on ADV measurements. The discontinuity in the shear rate is not visible in the DES numerical results of Koken and Constantinescu [10] and is also not present in the results of Truong et al. [11] (ADV measurements), obtained in slightly different conditions where the array of cylinders is placed in a floodplain separated from the main channel by a gently sloping bank.

In all the above cases, independently of the derivative of the shear rate, the flow develops conspicuous coherent structures, similar to those generated by an inviscid linear mechanism such as the Kelvin–Helmholtz instability [12] or other mechanisms, not necessarily linear [13, 14] and not necessarily inviscid (Gaster [15] or review in Schmid and Henningson [16]). These coherent structures have been observed in free mixing layers [17, 18], in shallow mixing layers [10, 19,20,21], in shallow wakes [22], shallow flows in compound channels with wall roughness only [23,24,25] or with obstructions in the floodplain [11], channel confluences [26] or shallow flows laterally obstructed by arrays of cylinders [2, 3, 9, 10, 27, 28].

It has been observed that the growth of instabilities in shallow parallel flows is inhibited by wall resistance, which prompted Chu et al. [29] and Alavian and Chu [30] to propose a bed-friction number and a critical value for that number, beyond which instabilities are expected not to grow. Chu and Babarutsi [19] proposed a critical value of 0.09 for shallow mixing layers. Van Prooijen and Uijttewaal [31], performing a linear stability analysis similar to Daoyi and Jirka [22], showed that the growth rate of the dominant mode (the wave number with maximum energy density, not the most unstable wavenumber) decays before the critical bed-friction number is reached. They propose that the critical bed friction number should be interpreted as the threshold beyond which all modes decay and devaluate its general usefulness to describe the dynamics of the shear layer.

In the case of shallow flows partially obstructed by arrays of cylinders, it is observed that the growth of the shear layer is arrested after a given longitudinal excursion that should depend, among other factors, on \(H/\left({C}_{D}a\right)\) (where H is the flow depth, \({C}_{D}\) is the array drag coefficient and \(a\) is the projected solid area per unit volume), judging from the numerical results of Koken and Constantinescu [10]. The shear layer thickness and the momentum thickness appear to attain equilibrium values, as is the case of other shallow shear flows such as those in compound channels [24].

The width of the shear layer inside the vegetation array scales with \({\left({C}_{D}a\right)}^{-1}\) [2]. In this layer, adjacent to the interface, there is mean momentum exchange which prompts White and Nepf [2] to call its width a penetration width. However, White and Nepf [2, 3] or Koken and Constantinescu [10] show that “sweep” events in the horizontal quadrant (the streamwise velocity fluctuations \({u}^{^{\prime}}\) are positive and the spanwise velocity fluctuations \({v}^{^{\prime}}\) are negative, in an axes system featuring with the transversal coordinate \(y<0\) in the array) may transport momentum deep into the cylinder array. These events are associated with strong coherent structures that do not necessarily restrain themselves to the mean shear layer. This is equivalent of finding instantaneous eddies spanning outside the mean shear layer, as observed by Stocchino and Brocchini [32] in compound channel flows. The core of the most energetic eddies does not penetrate the cylinder array, except in the case of small \({\left({C}_{D}a\right)}^{-1}\) [2] or if the array is in a floodplain and three-dimensional effects are relevant [11].

It has been observed that the Strouhal number associated to the most energetic eddies resulting from the destabilization of the shear layer is approximately \(0.032\) if the length scale is taken as the momentum thickness [2, 9]. This is a somewhat surprising result since is the same as the normalized frequency of a free shear layer obtained in the infinite Reynolds number limit [17].

White and Nepf [2] noted that the flow inside the array featured a wave-like motion, attributed to the passage of the coherent structures resulting from the destabilization of the shear layer. This oscillatory motion was detected at the interface between the array and the main channel in the guise of fluctuations of free-surface and thought to be associated to out-of-phase \(u\) and \(v\) time series. The numerical results of Koken and Constantinescu [10] show regions of high and low streamwise velocity with concomitant oscillations in the wall shear stress, which may be interpreted as a confirmation of the existence of this wave-like motion. It is known that free-surface oscillations can occur in sufficiently dense arrays of emergent stems placed across the full channel width [33, 34], but these oscillations are not coherent across the width of the channel and are not detectable in the velocity signal far from the free-surface.

As in other open-channel flows, secondary currents have been observed by Nezu and Onitsuka [27] in arrays with low submergence. However, there is little evidence of secondary currents in the set-up of Tong et al. [35], featuring a lower solid volume but fully emergent conditions. In the case described by Nezu and Onitsuka [27], the secondary flow forms a whirling structure with positive streamwise vorticity, with spanwise velocities directed to the cylinder array in the upper parts of the channel and directed out of cylinder array near the channel bottom. It has not been established if this secondary flow is a feature expectable in open-channel flows with lateral arrays of stems, emergent or submerged, or if it is expectable only in submerged arrays.

This paper is aimed at clarifying how the secondary flow is articulated with the wave-like motion in free-surface flows partially obstructed with emergent stems and how both depend on the shape of large eddies associated to the inflectional instabilities. To fulfil this aim, we (i) collect further evidence for a better characterization of the oscillatory flow inside the array, including the wave-like motion in the longitudinal direction, (ii) investigate the large-scale eddies resulting from the growth of instabilities as a cause of the oscillatory flow and (iii) investigate how the dynamics of the large eddies imply both the oscillating flow in the longitudinal direction and secondary currents.

The main findings result from the interpretation of the laboratory data. The parameters that characterize the experimental tests, laboratory facilities, experimental procedures, and instrumentation are described in Sect. 2. In Sect. 3, we present first and second-order moments of the turbulent flow and show that they are consistent with previous observations. In Sect. 4 we characterize the wave-like motion inside the array and discuss the mechanisms by which it determines secondary motion.

2 Experiments

Two different areal stem densities were tested in a laboratory facility at the Laboratory of Fluvial Hydraulics and Structures of Universidade da Beira Interior (Fig. 1). The tests were named R1 and R2. The hydraulic channel is horizontal and is 12.60 m long, 0.80 m wide and 0.70 m deep. The bottom and the left wall are made of concrete and the right wall is composed of eight glass panels allowing for flow visualization. All surfaces are hydraulically smooth. The water flow is pumped from a reservoir, below the channel, with a capacity of 3.5 m3, through a pressurized system and an electric pump group. The flow discharge is monitored by an electromagnetic flowmeter, with an error of ± 2%, installed in the discharge pipe. Downstream of the channel there is an adjustable tailgate to set the flow depth (H) during the experiments.

To curb large scale turbulent structures, the channel inlet includes an acceleration ramp and honeycomb diffusers. The array of cylinders is substituted by a brick corridor, 3.20 m long, to shorten the length necessary to achieve the equilibrium distribution of momentum spanwise across the channel.

The array of emergent stems is 6.00 m long and 0.30 m wide, from the right wall. Each stem is a circular cylinder. The array simulates, in the laboratory environment, vegetation with a quasi-rigid behavior found in the riparian corridor of watercourses, as in Maji et al. [36], Caroppi et al. [37], Caroppi et al. [38], Zhang et al. [39], Farzadkhoo et al. [40]. In this study, we employ rigid cylinders with 0.01 m diameter and 0.15 m height arranged in a staggered pattern with two different densities.

The three components of velocity, \(u\), \(v\) and \(w\) in the \(x\) (streamwise), \(y\) (spanwise) and \(z\) (vertical) directions, respectively, were acquired in three cross-sections normal to the channel axis (I, II and III, Fig. 1a), between \(x=7.50\) m and \(x=8.50\) m, spaced apart 0.50 m. Each cross-section is composed of a matrix of sampling points: seventeen (Test R1, Fig. 1b) or twenty (Test R2, Fig. 1c) in the spanwise direction and thirteen in the vertical direction (Fig. 1a). In test R1, the distance between measuring points in the spanwise direction is 3.30 cm. In test R2, sampling points are laterally spaced apart 2.25 cm in the array and 3.30 cm in the main channel. No point was less than 5 cm away from the walls to avoid interference in measurements. The vertical distance between measuring points is 0.30 cm, with the first point 0.30 cm from the bottom (Fig. 2a).

The 3D flow velocity measurements were performed with a down-looking ADV Vectrino (Acoustic Doppler Velocimeter), with the cylindrical sampling volume (6 mm diameter and 4 mm tall) at approximately 5 cm below the transmitter, and with accuracy of ± 0.5% of measured value ± 1 mm/s. The sampling frequency was 100 Hz and the sampling duration was 3 min (18,000 samples). An automatic 3D positioner, see Fig. 2b, was designed to guarantee the ADV verticality and to place it automatically and accurately in a pre-defined location, featured a movement accuracy of ± 1 mm. Although care was taken to maintain the limit correlation of 70% and signal-to-noise ratio above 15 dB, the data collected by the ADV needed to be post-processed to remove spikes. For that matter, we used the phase-space threshold method [41] as modified by Wahl [42], with no replacement.

The gradient of the free surface of flow \(dH/dx\) along the channel was evaluated with a point gauged installed on a mobile support, with an accuracy of ± 0.1 mm.

The flow discharge was \(Q=0.029\) m3s–1 in both tests. The downstream water depth was set at 0.10 m. Since the channel is horizontal, both flows were gradually varied. It was found that \(dH/dx\) was \(\approx\) 0.0008 for Test R1 and \(\approx\) 0.0011 for Test R2. The variation of the flow depth at the measurement section, between \(x=7.5\) m and \(x=8.5\) m was thus \(O\left({10}^{-3}\right)\) m.

The values of the main variables and parameters that characterize the tests are summarized in Table 1. The frontal projected area per unit volume is \(a=nd\), were \(n\) is the number of stems per unit area and \(d\) is the diameter of the cylinders, with solid volume fraction\(\phi =\pi {d}^{2}n/4\). We employed \(n=500\) stems/m2 and so \(\phi =0.0393\) for Test \(R1\), and \(n=1034\) stems/m2\(\phi =0.0812\), for Test \(R2\). The spanwise-averaged velocity in the inner part of the array is\({U}_{1}\), the peak velocity in the main channel is\({U}_{2}\), the convection velocity is \({U}_{c}=\left({U}_{1}+{U}_{2}\right)/2\), the differential velocity is \(\Delta U={U}_{2}-{U}_{1}\), the velocity ratio is \(\lambda =\Delta U/\left(2{U}_{c}\right)\), the drag coefficient \({C}_{D}\) for the vegetation array was quantified, as White and Nepf [3], from \({C}_{D}a{{U}_{1}}^{2}/2=-gdH/dx\), where \(g\) is the acceleration of gravity, neglecting the contribution of turbulent and dispersive stresses and assuming equilibrium between the drag force and the imbalance between hydrostatic pressure forces between two arbitrary cross-sections. The group \({C}_{D}a\) is the drag density parameter. Reynolds numbers of \(O\left({10}^{4}\right)\) are defined for the open channel, \({Re}_{H}={U}_{2}H/\nu\), where \(\nu\) is the kinematic viscosity of the fluid. The stem-Reynolds number, \({Re}_{d}={U}_{1}d/\nu\), is \(O\left({10}^{2}\right)\). The Froude number of the main channel is \(Fr={U}_{2}/\sqrt{gH}\). Both flows are hydraulically sub-critical and turbulent. The values of the stem-Re show that a Von Kárman vortex street is expected to occur in the wake of each cylinder. Given the area stem density, it is expected that vortex shedding occurs independently at each cylinder, from the instabilization of the viscous boundary layer at that cylinder [34].

It is important to note that the values in Table 1 were calculated from the measurements taken at approximately mid-depth (\(z/H=0.39\)), a criterion already used in previous investigations [2, 3, 9, 43, 44].

3 Mean flow and turbulence

Between the plateaus of constant velocities, within the vegetated area (\({U}_{1}\)) and in the center of the main channel (\({U}_{2}\)), there is a shear layer (Fig. 3), whose main parameters are quantified in Table 2. The thickness of the inner mixing layer is \({\delta }_{I}\) and of the outer shear layer is \({\delta }_{0}\), estimated as suggested by White and Nepf [2] employing the definition of the hyperbolic tangent profile and a boundary layer analogy. The momentum thickness is \(\theta ={\int }_{-\infty }^{+\infty }\left[1/4-{\left((U\left(y\right)-{U}_{c})/\Delta U\right)}^{2}\right]dy\). The slip velocity is\({U}_{s}=U\left({y}_{0}\right)-{U}_{1}\), \({y}_{0}\) is the coordinate where inflection point of the streamwise velocity is situated, and \({U}_{m}\) is the velocity at the matching point,\({y}_{m}\), at which the velocity and the slope of the inner and the outer layer matches. The lateral shear velocity is \({u}_{*}=\sqrt{m\acute{a} x({u}^{^{\prime}}{v}^{^{\prime}})}\). The Reynolds number of the mixing layer is defined as \({Re}_{\theta }=\Delta U\theta /\nu\).

It was previously observed by Caroppi et al. [9] that large-scale inflectional instabilities appear for \(\lambda >0.40\). The interaction of the channel with the vegetated area is much influenced by the magnitude of the vegetative drag. White and Nepf [2] argued that the width of the shear layer in the vegetation array is a function of \({C}_{D}a\), a claim verified by Caroppi et al. [9, 38].

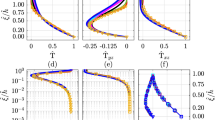

Figure 3 shows the spanwise distribution of the streamwise velocity at \(z/H=0.39\), in the three measurement sections of each test, \(R1\) and \(R2\). For both tests, within the vegetation and at the center of the main channel the streamwise velocity becomes close to constant, \(u\approx {U}_{1}\) and \({U}_{2}\), respectively. Across the interface, in the mixing layer, the profile is inflectional, similar to that of other canopy flows [3, 45, 46]. Test \(R2\) has a higher vegetation density and, thus, a higher spanwise gradient of the longitudinal velocity and a smaller penetration of the shear layer into the canopy. The thickness of the shear layer, \({\delta }_{I}\), is also smaller in test R2 (Table 2).

The lateral profile of turbulence intensities, \({\sigma }_{u}\), presented in Fig. 4, has a very similar development for the three sections of the two test runs. The values of \({\sigma }_{u}\) reach a maximum at the interface on the side of the central channel. Turbulence is more intense in the case of the highest density (R2). It was observed that the spanwise gradients are higher on the side of the vegetation and that the turbulence intensity in the vegetation corridor is lower than in main channel. Moreover, Fig. 4b indicates that the spanwise gradient of \({\sigma }_{v}\) is less pronounced than that of \({\sigma }_{u}\) and that the peak of \({\sigma }_{v}\) is slightly deviated towards the main channel. This fact was also observed by Nezu and Onitsuka [27].

As a matter of consistency, we found relevant to qualitatively compare the results of experimental tests with the results observed experimentally by White and Nepf [2] and numerically by Koken and Constantinescu [10]. We point out that it is possible to make a direct comparison of the present results with the experimental results obtained by White and Nepf [2] with the solid volume fraction, \(\phi\), ranging from 0.02 to 0.1 and numerical results from Koken and Constantinescu [10] with \(\phi\) ranging from 0.02 to 0.08.

Figure 5 shows the normalized profiles of the longitudinal velocity in the spanwise direction. The shaded area is the envelope of the experimental results of White and Nepf [2] and the dimensionless mean velocity profiles of Koken and Constantinescu [10] are the dashed lines.

The profiles of the normalized velocity in the inner layer \(\left(u-{U}_{1}\right)/2{U}_{s}\) versus an inner-layer coordinate \(\left(y-{y}_{0}\right)/{\delta }_{I}\) are plotted in Fig. 5a. For the outer layer, Fig. 5b shows the normalized velocity \(\left(u-{U}_{m}\right)/\left({U}_{2}-{U}_{m}\right)\) versus an outer-layer coordinate \(\left(y-{y}_{m}\right)/{\delta }_{0}\). Both the inner-layer and the outer layer profiles show a good agreement with the previously published data. There are, however, some differences, namely near the origin (\(y=0\)) that may be attributable to the measurement technique. We did not remove stems to conduct the measurements (Fig. 1b and c) while the results of White and Nepf [2] were obtained as trench-averaged results.

Similarly to what was done for velocities, the Reynolds stresses were also normalized with the maximum stress at the interface, \(\stackrel{-}{u{^{\prime}}v{^{\prime}}}/{u}_{*}^{2}\), and plotted against both coordinates in Fig. 6. In agreement with the observations by White and Nepf [2], in the inner-layer profiles there seems to exist spatial fluctuations due to the modulation of turbulence heterogeneity by stem patterns (Fig. 6a).

4 Evidence of wave-like motion

We analysed times series of velocity fluctuations and spectral density functions to examine the oscillatory motion in the riparian corridor and adjacent flow.

The power spectral density function shows that the dominant frequency at the interface is very close to the natural frequency of the inviscid Kelvin–Helmholtz eddies in shear flows. The Strouhal number, \({S}_{t}={f}_{ml}\theta /{U}_{c}\), for R1 III and R2 III is equal to \(0.038\) and \(0.035\), respectively, where \({f}_{ml}\) is the dominant frequency. There is also evidence of two-dimensional turbulence, with a slope of \(-3\) at frequencies higher than the Strouhal frequency of the mixing layer. At higher frequencies the power spectral density functions show Kolmogorov’s \(-5/3\) slope associated to locally isotropic and homogeneous turbulence. As is the case of the flows described by White and Nepf [2], Koken and Constantinescu [10] this is evidence that, in both tests, mass and momentum exchanges in the mixing layer are dominated by essentially two-dimensional large-scale structures akin to inviscid Kelvin–Helmholtz eddies.

We organize the power spectral density functions of the longitudinal and transversal velocity fluctuation as spectrograms, seen in Figs. 7, 8 and 9, to highlight the spanwise influence of the large-scale eddies. Note that, in Figs. 7, 8 and 9, the frequency \(f\) has been normalized as a Strouhal number.

Figures 7, 8 and 9 show that the high energy density associated to the Strouhal frequency of the mixing layer is registered across the entire width of the vegetation corridor. The energy content of the dominant frequency progressively decreases as it moves away from the interface, but the modulation of both the longitudinal and lateral velocity signal seems the same, well beyond the limits of the shear layer, in fact extending to the lateral boundary. This modulation configures the wave-like motion, as described by, e.g., White and Nepf [2], Koken and Constantinescu [10].

We note that outside the shear layer, as defined in this work, there is no net lateral momentum transport. We thus conclude that the wave-like motion should be associated to the large eddying motion (the dominant frequency is the same) but that such an oscillatory motion can only be extended to the side walls by continuity alone.

A relevant feature in the longitudinal velocity fluctuation spectrogram (Fig. 7) is that large scales, scaling with the depth of the channel, containing an appreciable amount of energy were registered in the middle of the main channel. These large scales are not present within the vegetation, which indicates that the riparian corridor seems to play a role in suppressing large-scale structures. In this corridor, the only relevant spectral signature is that of the oscillations associated with the wave-like motion. The energy content associated to the Von Kármán street is not clearly identified. Figure 9 shows that the wave-like motion was also registered near the bottom. Thus, it is significant to mention that the flow is oscillatory throughout the water column, being much stronger outside the vegetation and extending beyond the middle of the vegetation.

The wave-like motion has also a vertical component. The oscillations in the x–z plane are visible in the time series of both the streamwise and vertical velocities at \(z/H=0.39\) and at the interface (Fig. 10). It is observed that, in general, the large peaks of longitudinal velocity are accompanied by troughs in the vertical velocity. In this sense, the vertical motion is in counter-phase with the longitudinal motion, which indicates strong sweep events and hence, high peaks of the bottom shear stress, as suggested by Koken and Constantinescu [10]. However, the vertical motion seems to have a more complex pattern of oscillations.

The tendency for oscillatory is depicted in Fig. 10, which shows a time series of streamwise and vertical velocity registered at the interface. These time series clearly exhibit that the streamwise and vertical velocity are out-of-phase, which together are a dominant contribution to maximize the Reynolds stress.

5 Characterization of the large-scale eddy in its own frame of reference

5.1 Reconstructing the Eulerian flow field in the frame of reference of the large eddy

The eddying motion resulting from the growth of the inflectional instabilities can be observed in the time series of streamwise and spanwise velocities in the form of out-of-phase oscillations (Figs. 11 and 12). These are quasi-periodic fluctuations featuring inflows (\(u{^{\prime}}>0\) and \(v{^{\prime}}<0\)) and outflows (\(u{^{\prime}}<0\) and \(v{^{\prime}}>0\)) along the vegetation interface. The stronger these fluctuations the larger the average Reynolds stresses. Evidence of these oscillations as cause by a horizontal eddy, has been reported by Naot et al. [47], Nezu and Onitsuka [27] and White and Nepf [3].

Coherent structure can be detected by several methods, including thresholding time series of shear stresses, the identification of transverse velocity zeros, or even identification procedures that mainly use subjective thresholds and visual inspection of the time series [2, 48, 49]. If spatial data is available and if these structures are rotational, Galilean-invariant techniques such as the Q-criterion, can be used. If the frame of reference is not ambiguous, the streamline pattern is a powerful tool to recognize eddying motion.

Our data consisted of time series acquired in a matrix of points in cross-sections. To further understand the wave-like motion, we needed a spatial description of the mean large-scale eddy resulting from the instability of the inflectional profile. We reconstructed the large-scale eddy with a technique similar to that of White and Nepf [2]. The spanwise velocity time series \(v\left(t\right)\) was first subjected to low-pass filtering. A set of large-scale events was selected encompassing three consecutive zero crossings. The middle zero identifies the core of the coherent structure, and the adjacent zeros define the extremities of the structure. The signal is thus segmented into an ensemble of large eddies. The mean period of the ensemble, \({T}_{d}\) is, is calculated as the mean of the duration of its members (mean of the time difference between the first and the third zero crossings). Each member of the ensemble is then rescaled to obtain the new time coordinate \(\tilde{t }={T}_{d}\left(t-{t}_{0}\right)/{T}_{i}\), where \({T}_{i}\) is the period of the \({i}_{th}\) member of the ensemble, \(t\) is the instantaneous raw time of the ADV measurement and \({t}_{0}\) is the time for which the first crossing zero occurs.

Phase-averaged velocities, \({u}_{pa}\), \({v}_{pa}\), and \({w}_{pa}\), were then obtained by averaging the corresponding phase velocities over all the members of the ensemble. It is important to note that for this ensemble average the original (unfiltered) time series were used. Assuming Taylor's hypothesis, which postulates that eddies are advected by the mean flow for short distances, maintaining their size and attributes, the temporal scale was converted into a spatial scale by multiplying by the advection velocity.

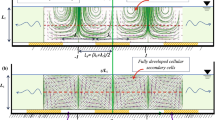

The result is the ensemble-averaged flow field observed in a frame of reference that moves with the velocity of the large-eddy. Figures 13 and 14 show the streamline pattern of this flow at mid-depth (\(z/H=0.39\)) and near the bottom (\(z/H=0.09\)), in the case of R1, and at mid-depth, for R2.

Figures 13a and 14 show that, the structure is not symmetrical relatively to a plane parallel to the interface. Given that the large eddy resembles an ellipse, we will use the terms major axis for the dimension of the rotational core in the longitudinal direction and semi-minor axes to stand for the spanwise extension of the structure. First, we note that semi-axis that extends inwards into the vegetation corridor is smaller than the semi-axis that extends outward to the main channel. It is apparent that the interaction with the vegetation array limits the lateral extent of the large eddy and, hence, lateral turbulent momentum exchanges and the width of the mixing layer. This had been observed before by e.g., White and Nepf [2, 3].

Another breakdown of symmetry, this one unreported before, is the conspicuous tilt of the major axis of the structure at \(z/H=0.39\), relatively to the axis of the channel. The observation of Fig. 13a, for instance, reveals that the front of the large eddy leans towards the side wall \(y=0\) while it back leans towards the main channel. This misalignment is not evident at the lower measurement plane. We note that, as a consequence of this misalignment, the lateral and the longitudinal velocities sampled along a line in the \(x\) direction that includes the center of the large eddy, become out of phase. This feature is seen in Fig. 15, for test R1.

The pattern of streamlines in Figs. 13 and 14 shows that away from the core, the streamlines are wavy and that the flow is not rotational. This indicates that there is a wave-like oscillatory flow both within the array and in the open channel outside the shear layer. This complements the result, taken from the analysis in the spectral space, that these large eddies result in an oscillatory wave-like motion that extends across the entire with of the riparian corridor.

5.2 Turbulent momentum transport and Reynolds stress anisotropy associated to the large eddy

Observing the spanwise distribution of the Reynolds stresses associated to the phase-averaged motion, \({\tau }_{uv,ca}\), and to the complete flow (Fig. 16), it is concluded that the large-scale eddy is the major contribution to the Reynolds shear stress-about 85% and 70% of the peak shear stress in tests R1 and R2, respectively. It thus dominates turbulent fluxes and Reynolds stress anisotropy in the shear layer. We now turn to the characterization of these quantities.

To identify how the large scale structures penetrate the vegetated area and promote momentum exchanges, we conducted a quadrant analysis of the phase-averaged flow i.e. using the phase-averaged velocities \({u}_{pa}\) and \({v}_{pa}\).

Figures 17 and 18 show the quadrant plots corresponding to three representative locations of test R1, inside the vegetation corridor (Figs. 17a and 18a), in the interface (Figs. 17b and 18b) and in the main channel (Figs. 17c and 18c).

From Figs. 17b and 18b, and from Fig. 15, it is clear that the large eddy generates the equivalent of a sequence of sweep and ejection events in the \(x-y\) plane and at mid-depth. For an observer standing at the interface, in an observation window fixed in the frame of the channel, the arrival of the large eddy represents a strong inrush of fluid, i.e. longitudinal velocity higher than the average and negative lateral velocity (directed towards the vegetation corridor). As the large eddy traverses the observation window, the flow reverses its direction. The large eddy leaves the observation window as a strong outrush, drawing fluid from the vegetation corridor to the main channel. This sequence is stronger at mid-depth than near the bottom. In fact, the Reynold stress anisotropy associated to this sequence is seen to be higher in Fig. 17b than in Fig. 18b.

Observing Figs. 17a, c and 18a, c, we note that there is a tendency towards an isotropy within the vegetation corridor and in the center of the main channel, as previously observed by Penna et al. [50]. This means that there is no net lateral turbulent momentum transport in the center of the channel or within the vegetation (Fig. 17a and c).

We now turn our attention to the motion in the \(y-z\) plane. We note that if the mass of the flow inrush associated with the arrival of the large eddy is perfectly balanced by the mass of the outrush, there is no flow in the vertical direction. The hypothesis of zero \(z\)-velocity seems inconsistent with the change in the asymmetry of the large eddy over the flow depth since it would be expected that different combinations of velocity gradients in the same vertical would, at some location, deliver a non-zero \(\partial w/\partial z\). We also note that if there is flow in the vertical direction, its fluxes are either self-balanced over the length of the large eddy, in an Eulerian sense, or there is necessarily a secondary current since the upper and lower boundaries (free-surface and bottom of the channel) are material surfaces.

To settle these matters, we have calculated the vertical velocities and the vertical gradients of the vertical velocity in the for \(z/H=0.39\) and for \(z/H=0.09\). All results are relative to the phase-averaged velocity field seen in the reference frame of the large eddy.

5.3 Vertical veloctities in the \({\varvec{y}}-{\varvec{z}}\) plane

Figures 19 and 20, corresponding to tests R1 and R2, show the spanwise distributions of the vertical velocity for two representative cross-sections, at the front of the eddy (Figs. 19a and 20a) and at the back of the eddy (Figs. 19b and 20b).

We will refer to the left and the right of the eddy adopting the view of an observer moving with the eddy looking upstream. Left is towards the sidewall of the channel and right is towards the main channel. At the representative cross-section at the front of the eddy, from left to right, there is evidence of weak upwelling (next to the channel wall), downwelling on the left of the eddy, upwelling, at right of the eddy and downwelling in the main channel.

At the representative cross-section at the back of the eddy, one finds the reverse succession of upward and downward velocities: at the channel wall, there is (weak) downwelling, at the left of the eddy there is upwelling and at the right of the eddy there is downwelling. The loci of the local extrema and of the zero crossings are different, which we believe is a consequence of the eccentricity of the axis of the large eddy, at \(z/H=0.39\). The values of the local maxima and minima are also not the same, the back and at the front. Based on this evidence, we hypothesize that the net downward mass flux generated at the front left of large eddy is not balanced by the upward flux seen that the back left. By the same argument, the upward and downward fluxes and right of the eddy, seen to be in counter-phase with those of the left, do not balance either. If these fluxes cancelled each other, we would have the self-balanced vertical motion over the length of the large eddy that does not require lateral flow to obey mass conservation. If, on the contrary, the vertical fluxes are not self-balanced, mass conservation requires the existence of flow in the spanwise direction—in short, secondary currents in the \(y-z\) plane.

It is of course well-known that these open-channel flows, with a riparian corridor, do develop secondary currents [27]. Our aim is thus not to show that they exist but to propose a conceptual model that has secondary currents as a necessary feature associated to the transit of large eddies.

5.4 Vertical gradients and Lagrangian analysis in the reference frame of the large eddy

Before we present the Eulerian conceptual model, we attempt a description of the motion of a particle in the phase-averaged flow field in the reference frame of the large eddy. Defined this way, the flow is steady and, hence, the streamlines are the same as pathlines.

We know the longitudinal and lateral velocities as a given particle circulates the large-scale eddy. We now derive the trend of the vertical velocity variation. We first apply the continuity equation, \(\partial w/\partial z=-\left(\partial u/\partial x+\partial v/\partial y\right)\), to the phase averaged flow to obtain the vertical velocity gradients. It is possible to do so since the continuity equation is Galilean invariant, therefore independent of the frame of reference.

Figures 21a and b show the vertical velocity gradients for test \(R1\), at mid-depth and near the bottom, respectively. The gradients are spatially distributed essentially in an antisymmetric way. At the front left of the large eddy, at \(z/H=0.39\), the vertical gradient of \(w\) is positive while \(w\) itself is negative. Hence, it is expected that at larger depths, the vertical velocity is also negative. As the bottom approaches, this tendency must be reversed since \(w=0\) at the wall. At the front right, the vertical velocity is positive and its vertical gradient is negative. Again, it is expected that, at greater depths the velocity is also positive and that the gradient is reversed near the bottom. At the back, the argument is the same—the signal of the vertical velocity is the opposite of its vertical gradient.

As seen above, as the eddy moves forward, it creates vertical movements that cause a particle to move to the bottom at its front, on the side of the vegetation corridor. Tracking a flow particle from point A, starting at mid depth (z/H = 0.39), one would find that, in the beginning of the movement, the particle tends to move towards the vegetation (Point B), initially upwards and then downwards. It should arrive at B at a higher elevation. From point B to point C, the particle travels down and then upwards. If the downwelling at B is stronger than the upwelling at C, the particle would have a net loss of elevation. The particle dips further as it approaches D. If the downwelling at D is stronger than the upwelling at A, the particle arrives at D at a lower elevation than at the starting point A. The cycle is repeated with greater amplitudes since the vertical gradients tend to increase the upwelling and downwelling motions as depth increases. Hence, it is expected that a particle starting at A for \(z/H=0.39\) arrives at E at \(z/H=0.09\). This cycle can only be maintained for elevations sufficiently far from the bottom. Near the bottom, where the gradients must invert, the particle is forced to move out of the large eddy. We thus expect that the large eddy loses coherence in the vicinity of the eddy. Since the flow is obstructed by the side wall at the left, it is expected that the result of this Lagrangian drift is a net movement towards the right, to the main channel.

We emphasize that this argument is only valid if the downwelling flow at the front left of the large eddy is stronger than the upwelling at the back-left (and reciprocally for the upwelling/downwelling motion on the right side of the eddy). In other words, the net downwards mass flux at the front-left of the eddy, in the vegetation corridor, is only partially recovered by the upward mass flux at the back.

6 A Eulerian conceptual model of secondary currents and wave-like motion

Streams with riparian corridors exhibit a mixing layer characterized by an inflectional spanwise profile of the longitudinal velocity. This inflectional profile is unstable and generates large scale eddies. Oscillatory motion has been observed in the riparian corridor and secondary currents have been registered across the channel width.

We now propose a conceptual model, within an Eulerian approach, establishing that both the wave-like motion and the secondary currents are necessary features of free-surface turbulent flows that develop large-scale inflectional instabilities.

We have seen that the large eddies are capable of periodically generate strong momentum exchanges inside the vegetation corridor, albeit contained in a narrow strip adjacent to the interface. We have also seen that these exchanges are in the form of sequences of lateral sweep and ejection events that originate mass fluxes not only in the horizontal plane but also in the vertical plane. These mass fluxes are registered as periodical variations of the longitudinal and vertical velocities in the riparian corridor. As seen in Fig. 10, the modulation of the longitudinal and vertical velocities is apparently not the same. However, the local maxima of the longitudinal velocity occurs simultaneously with local minima of the vertical velocity. This configures what has been described as the wave-like motion [2] and a possible cause of strong peaks in the near-bed shear stress [10]. This motion is thus a consequence of what may be termed a pumping mechanism by a standing observer, whereby the fluid is first given a lateral and downward motion by the arrival of the large eddy and then drawn back to the main channel, as the large eddy traverses.

This sequence of vertical mass fluxes of opposite directions is associated to the eccentricity of the axis of the large eddy relatively to the direction of the main flow. To show that the generation of secondary currents is associated with this eccentricity, we have developed a conceptual model of the flow, within an Eulerian framework. To do so we have reconstructed the horizontal velocity field but also the vertical velocities and the vertical gradients of these velocities in two horizontal planes. Based on this information we propose that the flow in two representative cross-sections, in the front and in the back of the eddy, is as shown in Fig. 22. In these cross-sections, the vertical velocities, their vertical gradients and the lateral velocities are consistent with the results shown in Figs. 13, 14, 19, 20 and 21.

The local maxima or minima of vertical velocities are associated with convergent streamlines. Loci of zero vertical velocity is associated with maximum horizontal (lateral) velocity. The consistency with the orientation of the lateral velocity determines the inclination of the convergent streamlines.

The model features flow cells that convey fluid from the locations of negative vertical velocities to the locations of positive flow velocities. There are three main cells under the riparian corridor, the large eddy and the main channel, adjacent to the vegetation corridor. The middle cell in the front cross-section corresponds to the circulation that harmonizes the observed downwelling on the front-left side of the eddy and the upwelling on the front-right side. Likewise, the middle cell in the back representative cross-section describes the circulation associated to the upwelling/downwelling motion in the right/left sides of the eddy. The position of these middle cells is a consequence of the eccentricity of the axis of the large eddy.

We now recall that this is an Eulerian flow description in the referential of the large eddy, which was reconstructed based on a phase-averaging operation. Hence, a spatial average along the \(x\)-direction and over the full length of the eddy retrieves the (Eulerian) flow field in the static reference frame of the channel. Although the flow along the length of the eddy is more complex than what is captured in the representative cross-sections, the simple superimposition of the flow patterns depicted in Fig. 23 explains some of the key flow features in the \(y-z\) plane.

Figure 23 shows the secondary motion in the \(y-z\) plane in the interface zone between the vegetation and the central channel, i.e. the values of the time averaged \(v\) and \(w\) velocity components acquired in the matrix of points of R1 III. The streamlines of the model are superimposed to the actual velocity field. Considering that the flow intensity is greater at front of the large eddie than at the back, it is concluded that the concatenation of the proposed streamlines in these two cross-sections of the eddie is compatible with the \(v-w\) velocity map. This shows that, at the interface, occurs a net mass flux directed tends towards the bottom and outwards to the main channel. As a result, there is a secondary circulation that carries mass and momentum off the vegetation to the main channel.

By employing phase-averaged quantities, we showed that the secondary motion, as seen in the Eulerian vertical-spanwise velocity field, is a necessary feature of these flows. The spanwise variation of Reynolds stress anisotropy can be related to the formation and growth of secondary flow. This is a key mechanism of generation of vorticity in the equation of conservation of vorticity in the longitudinal direction [51]. Unfortunately, we cannot compute the production terms associated to Reynolds stress anisotropy since we do not have enough spatial resolution in our data. However, we hint that, given the variation of anisotropy we found across the mixing layer, these may be Prandtl’s second kind of secondary motion [52]. We note that Nezu and Onitsuka [27] have observed a similar variation of Reynolds stress anisotropy and have thus assumed that the key mechanism for secondary currents in partially vegetated flows was Prandtl’s second kind.

7 Conclusion

Riparian corridors are often populated with quasi-rigid vegetation. In high-water conditions the drag on vegetation elements slows down the flow and generates a shear layer featuring an inflectional spanwise profile of the longitudinal velocity. This inflectional profile is unstable and generates large scale eddies. These are capable of periodically generate strong momentum exchanges inside the vegetation corridor. Inside the riparian corridor there is evidence wave-like motion, detectable as free-surface oscillations and out-of-phase velocity components. The analysis of the velocity field across the spanwise direction reveals a conspicuous secondary flow. This much is known from previous studies.

To further advance the knowledge on the hydrodynamics of open-channel flows with riparian corridors, we conducted a laboratory study to characterize the flow inside and adjacent to the corridor. We focused on unveiling the links among the large-eddy motion ensuing from the unstable inflectional profile, the wave-like motion inside the riparian corridor and the pattern of secondary currents.

We analyzed the power spectral density functions across the vegetation corridor and adjacent region, collecting evidence of the wave-like motion in the spectral space. We spatially reconstructed the large-scale eddy by phase-averaging velocity time series acquired in the spanwise direction and by converting it into spatial data using Taylor’s frozen turbulence hypothesis. We performed a quadrant analysis of the phase-averaged flow to determine the extent of lateral momentum exchanges and Reynolds stress anisotropy associated to the large-eddy. Finally, we analyzed the main kinematic features of the large-eddy in its frame of reference.

We showed that the turbulent momentum fluxes across the interface were mostly due to the large-scale eddy. They represent about 70%-85% of the peak Reynolds shear stress in the \(x-y\) plane. However, we observed that Reynolds stress anisotropy is only strong at the interface, in fact limited to a narrow band inside the riparian corridor. Anisotropy is gradually reduced towards the interior of the vegetation corridor.

While turbulent momentum fluxes associated to the large-eddy are not relevant inside the corridor, they set in motion large volumes of fluid, which, from mass conservation, have strong impacts over the entire channel width. From the perspective of a standing observer, the large-eddy is sequence of lateral sweep and ejection events. The first push fluid into the riparian corridor, the ejection draws fluid back to the main channel. The spanwise spectrogram of both longitudinal and lateral velocity fluctuations revealed that these mass fluxes are felt in the whole of the vegetated layer, as a consequence of continuity.

We showed, from the analysis of the large-eddy in its own referential, that the lateral sweep/ejection sequence is uneven and unequally distributed over the flow depth. This generates vertical flow with distinct upwelling and downwelling regions over the length and span of the large eddy.

We further showed that there is a net mass flux from the riparian corridor to the main channel. This mass flux is associated to an asymmetry of the large eddy relatively to the plane of the interface: the downwelling flux at the front of the structure is not compensated by the upwelling at its rear, in the riparian corridor. In the (Eulerian) flume frame of reference, this configures a pumping mechanism responsible for both the wave-like motion in the longitudinal direction and the secondary flow in the spanwise direction.

The wave-like motion is thus as a direct result of the sequence of vertical mass fluxes of opposite directions generated by the unevenness of the sweep/ejection sequence.

To show that secondary currents are embedded in the motion generated by the large eddy, we constructed an Eulerian flow model in its reference frame. It comprises circulation cells compatible with our measurements and calculations of the vertical and lateral velocities and vertical gradients of the vertical velocity over the length and width of the eddy. Spatially-averaging the model flow along the longitudinal direction, and over the length of the eddy, we retrieved the essential features of the velocity field in the \(y-z\) plane, namely the net mass flux from the riparian corridor to the main channel.

The key contribution of this research is to show that both the wave-like motion and the secondary currents are necessary features in free-surface turbulent flows that develop large-scale eddies resulting from the growth of inflectional instabilities.

We hint that the variation of Reynolds stress anisotropy across the mixing layer (in the spanwise direction) may configure a source of vorticity in the equation of conservation of the longitudinal vorticity. If that is the case, we present a structural mechanism of Prandtl’s second kind of secondary motion.

References

Devi TB, Sharma A, Kumar B (2019) Flow characteristics in a partly vegetated channel with emergent vegetation and seepage. Int J Ecohydrol Hydrobiol 19:93–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecohyd.2018.07.006

White B, Nepf H (2007) Shear instability and coherent structures in shallow flow adjacent to a porous layer. J Fluid Mech 593:1–32. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112007008415

White B, Nepf H (2008) A vortex-based model of velocity and shear stress in a partially vegetated shallow channel. Water Resour Res 44:W01412. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006WR005651

Scott ML, Friedman JM, Auble GT (1996) Fluvial process and the establishment of bottomland trees. Geomorphology 14:327–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-555x(95)00046-8

Lugo AE, Snedaker SC (1974) The ecology of mangroves. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 5:39–64. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.es.05.110174.000351

Tanino Y, Nepf HM (2008) Laboratory investigation of mean drag in a random array of rigid, emergent cylinders. J Hydraul Eng 134–1:34–41. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(2008)134:1(34)

Ferreira RML, Ricardo AM, Franca MJ (2009) Discussion of ‘Laboratory investigation of mean drag in a random array of rigid, emergent cylinders’ by Yukie Tanino and Heidi M. Nepf”. J Hydrol Eng 135:690–693. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)HY.1943-7900.0000021

Fjortoft R (1950) Application of integral theorems in deriving criteria of stability for laminar flows and for the baroclinic circular vortex. Geophys Publ Oslo 17:1–52

Caroppi G, Gualtieri P, Fontana N, Giugni M (2020) Effects of vegetation density on shear layer in partly vegetated channels. J Hydro-environ Res 30:82–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jher.2020.01.008

Koken M, Constantinescu G (2021) Flow structure inside and around a rectangular array of rigid emerged cylinders located at the sidewall of an open channel. J Fluid Mech 910:A2. https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2020.900

Truong SH, Uijttewaal WSJ, Stive MJF (2019) Exchange processes induced by large horizontal coherent structures in floodplain vegetated channels. Water Resour Res 55:2014–2032. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018WR022954

Drazin P (1970) Kelvin–Helmholtz instability of finite amplitude. J Fluid Mech 42:321–335. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112070001295

Lindzen RS (1988) Instability of plane parallel shear flow (toward a mechanistic picture of how it works). PAGEOPH 126:103–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00876917

Baines PG, Mitsudera H (1994) On the mechanism of shear flow instabilities. J Fluid Mech 276:327–342. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022112094002582

Gaster M (1962) A note on the relation between temporally-increasing and spatially-increasing disturbances in hydrodynamic stability. J Fluid Mech 14:222–224. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112062001184

Schmid PJ, Henningson DS (2001) Stability and transition in shear flows. Appl Math Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-0185-1

Ho C, Huerre P (1984) Perturbed free shear layers. Annu Rev Fluid Mech 16:365–424. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.fl.16.010184.002053

Yule AJ (1972) Two dimensional self-preserving turbulent mixing layers at different free stream velocity ratios, Aeronaut. Res. Counc. Rep. Memo. 3683, Dep. of the Mech. of Fluids, Univ. of Manchester, HM Stationery Office, London

Chu VH, Babarutsi S (1988) Confinement and Bed-Friction Effects in shallow turbulent mixing layers. J Hydraul Eng 114:1257–1274. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(1988)114:10(1257)

Booij R, Tukker J (2001) Integral model of shallow mixing layers. J Hydraul Res 39:169–179

Han L, Mignot E, Rivière N (2017) Shallow mixing layer downstream from a sudden expansion. J Hydraul Eng Am Soc Civ Eng 143:04016105. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)HY.1943-7900.0001274

Chen D, Jirka GH (1998) Linear stability analysis of turbulent mixing layers and jets in shallow water layers. J Hydraul Res 36:815–830. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221689809498605

Ghidaoui MS, Kolyshkin AA (1999) Linear stability analysis of lateral motions in compound channels with free surface. J Hydraul Eng ASCE 125:871–880. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(1999)125:8(871)

Proust S, Fernandes JN, Leal JB, Rivière N, Peltier Y (2017) Mixing layer and coherent structures in compound channel flows: effects of transverse flow, velocity ratio, and vertical confinement. Water Resour Res 53:3387–3406. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016WR019873

Bousmar D, Rivière N, Proust S, Paquier A, Morel R, Zech Y (2005) Upstream discharge distribution in compound-channel flumes. J Hydraul Eng 131(5):408–412. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(2005)131:5(408)

Rhoads BL, Sukhodolov AN (2004) Spatial and temporal structure of shear layer turbulence at a stream confluence. Water Resour Res 40:W06304. https://doi.org/10.1029/2003WR002811

Nezu I, Onitsuka K (2001) Turbulent structures in partly vegetated open-channel flows with LDA and PIV measurements. J Hydraul Res 39:629–642. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221686.2001.9628292

Zong L, Nepf H (2011) Spatial distribution of deposition within a patch of vegetation. Water Res Res 47:W03516. https://doi.org/10.1029/2010WR009516

Chu VH, W JH, Khayat RE (1983) Stability of turbulent shear flows in shallow channel. In: Proceeding of the 20th Congress of Int. Assoc. Hydraulic Research, vol 3, pp 128–133

Alavian V, Chu VH (1985) Turbulent exchange flow in shallow compound channel. In: Proceedings of the 21st IAHR Cong. Melbourne, Australia, pp 447–451. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(1991)117:1(21)

Van Prooijen BC, Uijttewaal WSJ (2002) A linear approach for the evolution of coherent structures in shallow mixing layers. Phys Fluids 14:4105–4114. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1514660

Stocchino A, Brocchini M (2010) Horizontal mixing of quasi-uniform straight compound channel flows. J Fluid Mech 643:425–435. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112009992680

Ricardo AM, Franca MJ, Ferreira RML (2010) Laboratory characterization of turbulent flow within a random array of rigid, emergent stems. In: Proceedings of the 1st IAHR Europe Congress, Edinburgh, Scotland

Ricardo AM, Koll K, Franca MJ, Schleiss AJ, Ferreira RML (2014) The terms of turbulent kinetic energy budget within random arrays of emergent cylinders. Water Resour Res 50:4131–4148. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013WR014596

Tong X, Liu X, Yang T, Hua Z, Wang Z, Liu J, Li R (2019) Hydraulic features of flow through local non-submerged rigid vegetation in the Y-shaped confluence channel. Water 11:146. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11010146

Maji S, Hanmaiahgari PR, Balachandar R, Pu JH, Ricardo AM, Ferreira RM (2020) A review on hydrodynamics of free surface flows in emergent vegetated channels. Water 12:1218. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12041218

Caroppi G, Västilä K, Järvelä J, Rowiński PM, Giugni M (2019) Turbulence at water-vegetation interface in open channel flow: experiments with natural-like plants. Adv Water Resour 127:180–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advwatres.2019.03.013

Caroppi G, Västilä K, Gualtieri P, Järvelä J, Giugni M, Rowiński P, (2019b) Comparative analysis of lateral shear layers induced by flexible and rigid vegetation in a partly vegetated channel. In L. Calvo (ed) Proceedings of the 38th IAHR World Congress (Proceedings of the IAHR World Congress). IAHR. https://doi.org/10.3850/38WC092019-1310

Zhang H, Wang Z, Dai L, Xu W (2015) Influence of vegetation on turbulence characteristics and Reynolds shear stress in partly vegetated channel. ASME J Fluids Eng 137(6):061201. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4029608

Farzadkhoo M, Keshavarzi A, Hamidifar H, Ball J (2019) Flow and longitudinal dispersion in channel with partly rigid floodplain vegetation. Proc Inst Civ Eng Water Manag 172:229–240. https://doi.org/10.1680/jwama.17.00079

Goring DG, Nikora VI (2002) Despiking acoustic doppler velocimeter data. J Hydraul Eng 128:117–126. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(2002)128:1(117)

Wahl TL (2003) Discussion of Despiking acoustic doppler velocimeter data by Derek G. Goring and Vladimir I. Nikora January. J Hydraul Eng 129:487–488. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(2003)129:6(484)

Ben Meftah M, De Serio F, Mossa M (2014) Hydrodynamic behavior in the outer shear layer of partly obstructed open channels. Phys Fluids 26:065102. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4881425

Ben Meftah M, Mossa M (2016) Partially obstructed channel: contraction ratio effect on the flow hydrodynamic structure and prediction of the transversal mean velocity profile. J Hydrol 542:87–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2016.08.057

Raupach M, Finnigan J, Brunet Y (1996) Coherent eddies and turbulence in vegetation canopies: the mixing layer analogy. Boundary Layer Meteorol 78:351–382. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00120941

Ghisalberti M, Nepf HM (2002) Mixing layers and coherent structures in vegetated aquatic flows. J Geophys Res Oceans 107(2):3–11. https://doi.org/10.1029/2001JC000871

Naot D, Nezu I, Nakagawa H (1996) Hydrodynamic behavior of partly vegetated open channels. J Hydraul Eng 122:625–633. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(1996)122:11(625)

Antonia R (1981) Conditional sampling in turbulence measurement. Annu Rev Fluid Mech 13:131–156. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.fl.13.010181.001023

Li Q, Fu Z (2018) Identifying the scale-dependent motifs in atmospheric surface layer by ordinal pattern analysis. Commun Nonlinear Sci Numer Simul 60:50–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnsns.2018.01.002

Penna N, Coscarella F, D’Ippolito A, Gaudio R (2020) Anisotropy in the free stream region of turbulent flows through emergent rigid vegetation on rough beds. Water 12(9):2464

Bradshaw P (1987) Turbulent secondary flows. Annu Rev Fluid Mech 19:53–74

Nikora V, Roy AG (2012) Secondary flows in rivers: theoretical framework, recent advances, and current challenges. In: Church M, Biron PM, Roy AG (eds) Gravel-Bed Rivers. Wiley, New York. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119952497.ch1

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank for the financial support of the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) through Project PTDC/ECI-EGS/29835/2017 - POCI-01-0145-FEDER-029835, financed by FEDER funds through COMPETE2020-Operational Program Competitiveness and Internationalization (POCI) and by National funds through FCT-Foundation for Science and Technology, IP.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visithttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Taborda, C., Fael, C., Ricardo, A.M. et al. Wave-like motion and secondary currents in arrays of emergent cylinders induced by large scale eddying motion. Environ Fluid Mech 22, 403–428 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10652-022-09863-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10652-022-09863-4