Abstract

This systematic literature review sought to reconcile the evidence of efficacy for interventions and approaches to enhancing self-regulation and/or executive function in preschool settings. Following PRISMA methodology, a comprehensive search of 20 years of intervention research identified 85 studies that met inclusion criteria. Interventions were categorised by intervention approach and coded for their characteristics (e.g. sample size, dose, duration, interventionist, intervention activities), outcomes (e.g. significance, size of effects) and study quality (i.e. risk of bias). Reconciliation of intervention results indicated (1) within intervention approaches, some approaches had more consistent and robust evidence of efficacy (e.g. mindfulness, mediated play, physical activity) and (2) across intervention approaches, characteristics that had greater (or exclusive) presence amongst the higher efficacy interventions (e.g. cognitive challenge, movement, as well as interventionist, fidelity and dose considerations). Implications for future intervention (re)design, and for theorising about mechanisms of self-regulation and executive function change, are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rationale

Achievement gaps during the schooling years can be largely traced back to differences in pre-academic and cognitive skill performance at school entry (Duncan & Magnuson, 2013). It is thus increasingly important that early childhood education provide children with the cognitive, social, emotional and physical foundations on which further skills can be built. The intentional development of self-regulation (SR) and executive function (EF) abilities appear particularly pertinent in this regard, given that research demonstrates that these domain-general constructs can be enhanced in preschool settings, nd underpin academic and social emotional competence (Baron et al., 2017; Blewitt et al., 2018, 2020; Carson et al., 2016; Maynard et al., 2017; Melby-Lervåg & Hulme, 2013; Scionti et al., 2020; Wood et al., 2020). Indeed, some researchers have considered SR and EFs to be the biological foundation for school readiness (Bierman et al., 2008; Blair, 2002) given that many of the skills associated with a successful transition to a formal school environment — such as being able to remember and follow rules, shift and maintain attention on the teacher or task at hand, get along with others and control emotions — rely on these abilities (Lyons & Zelazo, 2011; McClelland et al., 2017; Pianta & Rimm-Kaufman, 2006; Zimmerman, 2008). The demands and expectations of formal schooling for regulation-related behaviours adds impetus to the preschool period being an important time to target SR and EF development. Research positions this period as a window of opportunity for the cultivation of these important skills (Garon et al., 2008; Zelazo et al., 2016). As a consequence, the last two decades have seen intensified research efforts to develop, implement and evaluate short-term and long-term interventions targeting these abilities. Despite this attention, however, there remains little clarity about the early intervention approaches or characteristics for improving EFs and/or SR that yield greater consistency and strength of effects. The current review reconciles available evidence concerning preschool interventions targeting SR and/or EFs, to identify the process mediators (Jones et al., 2013), that are likely to promote successful and sustainable skills. We review programs that were implemented with typically developing children in pre-school settings. These programs focused on supporting continued SR or EF growth and preventing the emergence of developmental concerns.

Conceptualising Self-Regulation and Executive Functions

Self-regulation and executive functions have been conceptualised in a variety of ways, depending on the discipline (e.g. developmental psychology, neuroscience) (Schmitt et al., 2015). This has led to a range of terminology being used to describe both constructs, resulting in the ‘jingle-jangle fallacy’, where conceptual clarity is obscured, and confusion and ambiguity remain. For instance, several constructs have been linked to SR, including self-control (Boutwell & Beaver, 2010), effortful control (Rothbart & Jones, 1998) and EF (Garon et al., 2008). Yet there is little clarity regarding the distinctions or relations between these constructs, such as whether, when and how EFs relate to SR.

This lack of conceptual clarity is also found with EFs. Jones et al. (2016), in their ‘Executive Function Mapping Project’, identified over 40 unique terms associated with this construct. Although debate continues regarding the precise number of EFs, a prominent framework (Miyake et al., 2000) proposes that there are three core EFs: inhibitory control (IC) — stopping or suppressing predominant responses; working memory (WM) — holding and manipulating information in the mind; and cognitive flexibility (CF) — the ability to shift attention and to think in different ways. Several authors have emphasised that in real-life situations, tasks generally require an integration and interplay of these three EFs (Best et al., 2011; Diamond, 2013; McClelland & Cameron, 2012, 2019), thereby making it difficult to identify the extent to which a specific EF influences a behaviour, response or outcome.

In line with broad, yet prominent conceptions of SR as, “the regulation of processes by the self” (Baumeister et al., 2007, p.6), there is an implicit understanding that a cognitive control element (EFs) needs to be involved in order to intentionally and effortfully regulate our thoughts, emotions and behaviours, which makes SR possible (Blair & Raver, 2014; Huizinga et al., 2006; Zelazo & Carlson, 2012). This differs from regulation of the self, which may involve external influence: by someone or something else, such as a parent, teacher or the environment. According to this conception, self-regulation refers to an ability to control thoughts, behaviours and emotions in pursuit of goals, despite contrary impulses or distractions. EFs are higher-order cognitive process — to hold and work with information in mind, resist impulses and distractions and flexibly shift attention — that enables the control aspects of self-regulation.

Baumeister et al. (2007) posited that much of SR is subsumed under the EF term impulsive control, but note that, “strictly speaking, a person does not control the impulse itself, rather the behaviour that would follow from it” (p.17). They identify three factors upon which they theorise SR is dependent: (1) commitment to standards — there needs to be a goal, or an idea, of how the self ought to be; (2) monitoring by self and its behaviours in pursuit of that goal — a behaviour outside of conscious awareness is less likely to be a target for change or regulation; and (3) what is needed to change the self’s responses — the capacity to make the necessary changes to reactions and responses, (often in response to impulses that are tied to emotions), which is the role ascribed to EFs. It is this integral and integrated role of EFs which is necessary, but not sufficient for successful SR that points to the need for an integrative approach to be taken to the development of SR and EF abilities. Adopting a combined approach may, therefore, allow for less conceptual confusion, particularly at the classroom level, where cognitive and behavioural regulation can be intentionality developed simultaneously.

Evidence in Support of Adopting an Integrated Approach to Self-Regulation and Executive Functions

Although there is low consensus regarding exactly how SR and EF abilities are related, numerous studies demonstrate a bi-directional relationship across their development (Blair, 2016; Blair & Ursache, 2011; Becker et al., 2014; Howard et al., 2021a, 2021b). This is not surprising if viewed from a relational development systems theory perspective, which asserts that skills do not develop in isolation, and all development represents a bidirectional and dynamic process between the development of increasingly complex skills over time and across contexts (Blair & Raver, 2015; McClelland et al., 2015). While these results are correlational, they are suggestive of a critical link in a possible causal sequence, such that improving EFs could lead to an improved capacity for SR. Similarly, improving SR might allow children to engage in a wider range of EF-promoting activities, thereby providing opportunity to further develop EF.

Another plausible alternative to the bi-directional model is that proposed by McClelland and Morrison (2003), and empirically supported by Davis et al., (2021), that SR and EF are simply “manifestations of the same underlying self-regulation construct” (p. 631), referred to as ‘the common factor model’ (Finkel, 2011). The distinctions between the two constructs are a by-product of their different theoretical origins, rather than opposing frames of reference.

Therefore, adopting a more holistic approach and intentionally targeting SR and EFs concurrently, children’s capacity to thrive might be more likely, efficiently or effectively increased; setting children up for success as they transition to more formal learning environments.

Findings of Previous Reviews

Previous systematic literature reviews of intervention studies have tended to take either a broader approach in terms of included age range (Diamond & Ling, 2019; Jacob & Parkinson, 2015; Pandey et al., 2018), or a narrower approach, electing to focus on studies that developed either one or more distinct component of SR/EF in preschool contexts. The latter is evidenced in previous reviews on SR (Pandey et al., 2018; Robson et al., 2020); training of working memory using digital technology (Scionti et al., 2020; Melby-Lervåg & Hulme, 2013); mindfulness-based interventions (Bockmann & Yu, 2022; Maynard et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2021); physical activity (Carson et al., 2016; Wood et al., 2020); and specific curricula (Baron et al., 2017; Marshall, 2017). In addition, systematic reviews have also been conducted into the effectiveness of social and emotional (SEL) curriculum-based interventions in preschool settings to improve aspects of SR for both teachers and students (Blewitt et al., 2018, 2020; Stefan et al., 2022). These reviews provide evidence that it is possible to enhance SR/EF skills by targeted interventions, however, in all cases, results from interventions were mixed.

As such, there is a need to understand intervention characteristics that are associated with more likely and robust effects, merging SR and EF literatures given their seeming overlap. Focusing on either alone, or some subset of interventions targeting one ability, obscures the bigger picture, leading to siloed thinking. Amalgamating lessons learnt from both literatures has the potential to benefit the development of both concepts, particularly at an operational level within the preschool classroom.

Objectives of the Current Review

This review sought to address this issue through a systematic review of existing research on interventions specifically designed to enhance the development of SR/EF in preschool settings. Since they stem from different disciplines of research, they have rarely been investigated together (Neuenschwander et al., 2012). However, there is emerging recognition of the benefit of their integration (Hofmann et al., 2012; Sankalaite et al., 2021).

Given increasing ubiquity of preschool attendance and thus the opportunity to ensure practices in these settings optimise children’s developmental progress, the current review focused on interventions with preschool children in formal preschool services and settings. It aimed to synthesise the evidence from various approaches that have been taken to enhance SR/EF skills, additionally examining type, duration and intensity of intervention, facilitation of the intervention and outcomes considered and achieved. From these factors, the review sought to identify intervention characteristics associated with more likely and robust effects, to inform future intervention (re)design and for theorising about mechanisms of SR and EF change.

Methods

Information Sources

This review followed the PRISMA-P guidelines (Moher et al., 2015). Scoping searches were carried out to determine the current state of the research field and to fine tune the search terms. Subsequently a literature search was performed on 28 September 2020, and re-searched January 2021, to capture all the SR/EF intervention studies conducted with preschool age children in a preschool setting, that were published in peer reviewed journals between 2000 and 2020. A total of six electronic databases were accessed: A + Education, ERIC, Proquest, PyscINFO, SCOPUS and Web of Science, using the Boolean terms:

-

"executive function*" OR inhibition OR "inhibitory control" OR "impulse control" OR "effortful control" OR "behaviour* control" OR "behaviour* regulation" OR "executive control" OR "self-regulat*" OR "self-control" OR "executive attention" OR "working memory" OR switching OR "cognitive flexibility".

-

AND kinder* OR "early childhood" OR "pre-school*" OR preschool* OR "childcare" OR "day care*" OR nursery*.

-

AND intervention* OR program* OR Curriculum.

Inclusion Criteria

Studies were included in this review if the intervention aimed to enhance preschool children’s SR/EF; this included both direct training (e.g. a working memory computer training) and indirectly promoting them (e.g. physical activity). Studies focused on self-regulated learning (SRL) were also included since SRL falls within the wider construct of SR (Davis et al., 2021), being defined as the application of SR to academic learning. Studies had to take place in a preschool setting, with typically developing children between the ages of 3 and 6 years old. Within these samples, there were likely to be children with learning difficulties, however, studies focusing exclusively on children with documented disabilities, such as Attention Deficit Disorder, were excluded. Individual studies needed to include a control group (either active or passive), and pre and post measures of one or more EF (i.e. inhibitory control, working memory, cognitive flexibility) and/or SR outcome (e.g. behavioural, social-emotional) using validated tools for assessment, including task-based measures and behaviour questionnaires. All studies needed to be published in English, in a peer-reviewed journal between January 2000 and December 2020. We selected our date parameter to coincide with the publication of Miyake et al. (2000) seminal paper identifying three core executive functions. Theory and research to reconcile self-regulation and executive functions — in the manner conceptualised for this review — emerged following this publication.

Search Strategy

The initial search across the six databases generated 9115 results. These were imported into Covidence (www.covidence.org) for further review, this process identified 3288 duplicates. A single researcher screened each of the remaining 5827 studies by title and abstract against eligibility criteria. If a study appeared to meet the eligibility criteria, or the relevance of the study was uncertain, then full texts were obtained (n = 641). A randomly selected 321 (50%) were also independently screened by a second researcher, generating a Kappa score of 0.71 indicating substantial agreement (McHugh, 2012). Discrepancies were discussed and in those instances that a decision remained uncertain (1.38%), the studies were referred to the second author of this paper for mediation. From the original search, 78 studies were included in the final analysis. Seven further studies were added as a result of a final search for papers published in 2020, identified from the January 2021 re-search and a ‘snowball search’ branching backwards using Google Scholar.

Data Charting & Data Items

The 85 studies included in the review were then recorded in a PICO table and coded according to: date of publication, sample age, sample size, country where the study was conducted, study design, length and intensity of intervention, personnel leading delivery of the intervention, the measure(s) of SR/EF used, significance and size of the intervention’s SR/EF effects and any other significant non-SR/EF outcomes. Interventions were delivered by diverse interventionists: classroom teachers, psychologists, research facilitators and/or staff trained in a specific curriculum or speciality area. For ease of reporting, these were consolidated into external facilitator and teacher. The child outcomes from each study were recorded as being either statistically significant or non-significant for SR/EF, as reported by the authors. From the 85 studies, 73 reported an effect size or provided sufficient data to calculate an effect size from means and standard deviations.

For the remaining 12 studies, effect sizes were requested from the authors but were not acquired. Effect size reported or computed using established rules of thumb to interpret these as small, moderate or large (Cohen, 1992; Hedges, 1985). All final studies were assessed for study quality using the AXIS tool (Downes et al., 2016). This scale is designed to critically appraise the reporting quality of cross-sectional studies. It consists of 20 items such as justifying the sample size, using validated measures and reporting funding and conflicts of interest (see Supplementary Table 1). A random 12% of studies were independently assessed by two researchers using this tool, yielding a Kappa inter-reliability rating of 0.68 (p < 0.002), indicating substantial agreement (McHugh, 2012). Risk of bias was considered as another factor, in addition to intervention and study characteristics, by which to reconcile differences in intervention effects.

Synthesis of Results

Although there are various taxonomies that could be applied to classify SR and EF intervention approaches (e.g., those that intervene directly on children’s SR or EF versus those that aim to achieve this indirectly, such as training and influencing parent/educator practices with children), the current review builds on the work of Takacs and Kassai (2019) by using more nuanced categorisations. Specifically, four higher-order categories comprised of 12 distinct intervention approaches were identified, namely:

-

1. Play: engaging children in activities that are inherently fun, engaging and has potential to engage EF and/or SR, consisting of (i) mediated structured play or (ii) semi-structured creative play approaches.

-

2. Social-Emotional: enhancing children’s awareness of themselves and their interconnectedness with others, consisting of (iii) mindfulness or (iv) social-emotional learning (SEL) programs.

-

3. Curricula and Pedagogy: supplementing teacher knowledge and capacity to embed SR/EF training in domain specific contexts, consisting of (v) curricula, (vi) multicomponent training, (vii) music, (viii) mathematics, (ix) language training or (x) integrated arts programming.

-

4. Non-routine Activities: engaging children in novel activities or unique adaptations to everyday activity that are purposefully designed to promote SR/EF learning, consisting of (xi) task training (including digitalised) and (xii) physical activity.

It should be noted that two studies could have been assigned to more than one category when both were components of the intervention, namely: physical activity and digitalised training (Xiong et al., 2019); and music and Lego building (Bugos & De Marie, 2017). A further 13 studies evaluated two interventions that could be classified into different categories. In each of these cases, these multi-arm interventions reflected incremental gradations of a target intervention (e.g. mathematics with EF challenge, mathematics only and business-as-usual control) to better understand mechanisms of effect. As such, the category of assignment (and effects evaluated) was based on the stated emphasis and intent of the authors’ paper, to assign the one most appropriate category. Study results were synthesised separately for each of the 12 approaches. Where there was a discrepancy in the results, differentiating factors (i.e. EF vs SR intervention; program content/nature/delivery; dose and/or duration; interventionist, measure type/number) were evaluated to identify possible reasons for this discrepancy. The pattern of results for each of the 12 intervention approaches was then further reconciled in the Discussion to identify EF/SR intervention approaches, content and features that have comparatively more robust evidence for generating child-level effects.

Results

Study Characteristics

The characteristics of included studies are presented in Table 2 of the supplementary material. The studies sampled a total of 12,595 children, between the ages of 3–6. Of the 85 studies included, 72 (84.7%) were published between 2015 and 2020, highlighting increasing activity and diversity of approaches to early SR/EF intervention in preschool settings. For instance, the past 6 years have seen mindfulness (n = 12) become a prominent approach to enhancing SR and EFs. Sample sizes ranged from 20 to 877 participants, with a mean sample size of 148 (ơ ± 169.05). Just over half (n = 48) of the studies were conducted with sample sizes of less than 100 children. All studies involved both sexes, with a relative balance of boys (49.1%) and girls. External facilitators led the intervention in 52 (61.17%) of the included studies. Although 23 countries were represented in the corpus of studies, the majority of research was conducted in either North America (35.3%) or Europe (34.1%). Ten studies were from Asia, and each of Australasia and South America were the setting for seven studies. There were a further two studies conducted in the Middle East.

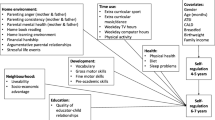

Of the 85 intervention studies included in this review, 59 (69.4%) had an exclusive focus on developing one or more EF abilities, 17 exclusively targeted SR and 9 studies targeted both SR and EF. Interventions that targeted SR and EF tended to target not only the EF components of SR, but also the nonexecutive components of SR (e.g. motivation and goal setting). That is, they took an integrative approach. The dose and duration of interventions varied widely, from a single period of 15 min to curricula running daily across an entire school year. The median intervention dose was 9 h (the mean was not possible to accurately estimate given unclear dose for full-year curriculum approaches). EF interventions tended to have a smaller dose and duration than those targeting SR (Fig. 1).

A variety of measurement approaches were used to assess SR/EF outcomes: exclusively task-based measures (n = 47 studies); exclusively behaviour rating questionnaires (n = 10 studies); a combination of both (n = 20 studies); observation plus task-based measures (n = 5 studies); observation supplemented by a questionnaire (n = 2 studies); and one study supplemented task-based measures with electroencephalogram (EEG) data to further assess children’s inhibitory control. A further breakdown shows that task-based measures were used in 51 (86.4%) EF-only studies, four (23.5%) SR studies and in all studies (n = 9) that aimed to improve both SR and EF. Head, Toes, Knees, Shoulders was the most frequently adopted task-based measure (n = 20) and was variously conceptualised as assessing EF (n = 9), SR (n = 8) or both (n = 4). Of the studies that used a behaviour rating questionnaire, 26 were completed by a teacher and nine by parents (some used both). A variety of questionnaires were used, however, the most common was the BRIEF-P (n = 7), which was construed as measuring either SR (n = 1) or EF (n = 6).

Intervention Efficacy

Statistically significant results (for at least one outcome) were reported in 60 (70.6%) of the studies; 43 (72.8%) EF interventions, 11 (64.7%) SR interventions and 6 (66.7%) of the combined SR/EF interventions. Across these studies, 208 effects were evaluated and 102 of these (49.0%) were statistically significant immediately following the intervention. Only four studies (Clements et al., 2020; Keown et al., 2020; Poehlmann-Tynan et al., 2016; Rosas et al., 2019) — all EF intervention evaluations — included follow-up assessments several months after the end of the interventions. The rest exclusively evaluated acute effects immediately on completion of the intervention. The effect sizes across all the studies (immediately following the intervention), included small (n = 29), small to moderate (n = 12), moderate (n = 7) small to large (n = 12), moderate to large (n = 3) and large effects (n = 10). Insufficient reporting precluded calculation of effect sizes for a further 12 studies. Interventions were characterised as comparatively higher in efficacy if they achieved: significant effects for at least 50% of the measured outcomes, at least one of with a moderate effect size; and/or a significant, large effect for at least one measured outcome and did not have a low risk of bias rating. Discussion of intervention efficacy follows, organised by the category and approach to intervention.

Play

A total of 1936 participants across 19 studies, adopting either a mediated or semi-structured play approach, are included in this category. They included activities that are inherently fun and engaging which have the potential to engage EF and/or SR.

Mediated Structured Play

Studies adopting this approach (n = 16) involved the direct teaching of SR (n = 4), EF (n = 11) or both EF and SR (n = 1) skills and strategies to children using games and stories. The average sample size was 99.25, ranging between 43 and 276. To ensure easy accommodation in preschool settings, activities in these interventions were usually undertaken in small groups and/or whole class in the classroom. Sessions were sometimes structured and sequenced, and at other times flexible and spontaneous; however, activities were commonly designed to enable an increase in cognitive complexity as children became more experienced with them. Interventions adopting this approach had an average dosage of 17.60 h, ranging from 1.75 h (1 × 15 min per week, over a 7-week period) to 72 h (3 × 2 h a week for 12 weeks). The majority of studies (n = 14) involved multiple sessions per week. Of the studies adopting this approach, 68.8% (n = 11) used external facilitators to implement the intervention.

Statistically significant effects acutely after intervention were reported for 75.00% (n = 12) of the interventions. Of the four exceptions, Rosas et al. (2019) reported significant effects 8 months after the intervention. Across these studies, 41 effects were evaluated, of which 26 (63.41%) were significant. Consolidating the results for each study, the effects reported were small (n = 5), small to moderate (n = 4), moderate (n = 1) and small to large (n = 4). Two studies did not provide sufficient data to calculate effect sizes.

Six of 16 interventions evaluated were characterised as comparatively higher in efficacy, based on the applied thresholds of significance and sizes of effects. One of these studies (Sezgin & Demiriz, 2019) was ultimately excluded from this group, given it had amongst the smallest sample sizes (n = 54 children), used sub-optimal analysis strategies (analysing post-test differences between intervention and control groups, rather than differences in change), and was rated comparatively high for risk of bias (13/20). This leaves open the possibility that effect size estimates were not directly comparable with those of the other studies. Indeed, although their intervention lasted 8 weeks at high intensity (3 times per week), this was comparable to two other studies adopting this approach that reported non-significant results (McClelland et al., 2019; Tominey & McClelland, 2011). Contrasting the higher- and lower-efficacy groups, there was little clear distinction in dose (low-dose interventions were overrepresented amongst the high-efficacy studies — max. 15 h over 6 weeks — although there were also low-dose studies outside this group). Factors that did appear to better distinguish higher-efficacy results were interventionist, target and measured outcome(s). Specifically, all studies reporting high efficacy used an external facilitator; there were also studies outside this group that used external facilitators, but it is notable that none of the teacher-led interventions achieved high-efficacy. There was also distinction in terms of the intervention target and the measured outcomes. All high-efficacy interventions targeted EF exclusively. There was also a pattern by which significant (and often larger) effects were found for WM and CF, with less consistent evidence for effects on IC, global EF or SR.

Overall, based on the rate and size of significant effects, the evidence is relatively robust in favour of this approach. However, the efficacy of interventions adopting this approach appeared to vary by interventionist, target and measured outcome.

Semi-structured Creative Play

Interventions taking a semi-structured creative play approach (n = 3) all sought to enhance EFs. These studies had sample sizes averaging 116 participants (range 59–179). The three studies differed in terms of their content; one was centred around block play and two on fantasy play. Their common thread was their emphasis on small group creative play activities where children were required to collaborate and regulate their actions towards a goal. Children were encouraged to be self-directed, which required them to plan, problem solve and negotiate with peers in a creative play-based context. Interventions were comparatively short in duration; individual sessions lasted 15–20 min, multiple times per week over a 5- to 7-week period (totalling 4.6 to 6.25 h). Intensity ranged from twice a week to daily sessions. All interventions were facilitated by external facilitators who started each session with a prompt in the form of a theme or challenge. Facilitators were not actively involved in the play, although they intervened to ensure engagement in the activities.

Significant effects after intervention were reported in 33.3% (n = 1) of the studies. Across the three studies 7 effects were evaluated, of which 2 (28.6%) were significant. Effects reported for each of the studies were small (n = 1), small to moderate (n = 1) or small to large (n = 1). One of the three intervention evaluations yielded evidence of high efficacy. There was no clear distinction between the high-efficacy and other interventions in terms of interventionist (all external facilitators), target (all EF), dose or duration. In terms of outcomes, WM was uniquely assessed in the high-efficacy study (yielding a large effect). As earlier, IC and global EF effects were not found. There was less consistent evidence for CF, which had a large significant effect in the high-efficacy study and a non-significant moderate effect in one less-efficacious intervention.

Albeit limited by the number of interventions and effects evaluated, there is not currently robust evidence in favour of this approach. However, high efficacy was possible and demonstrated, specifically in relation to WM.

Social-Emotional

A total of 4255 participants across 20 studies, adopting either a mindfulness or social-emotional learning approach, are included in this category. These approaches had an emphasis on enhancing children’s awareness of themselves and their interconnectedness with others.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness interventions (n = 12) sought to enhance EFs (n = 7), SR (n = 2) or both (n = 3) through developing socio-emotional competencies such as self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship management and responsible decision making. A typical feature of these interventions was sequenced activities involving the inclusion of self‐regulation of attention, by including one, or a combination of the following: mindfulness of the breath, body scan, mindful movement or mindful eating. All included studies were conducted since 2015, suggesting a recent growth in interest in this approach. The average sample size was 157.17, although this was highly variable across studies (ranging from 21 to 584). Similarly, the duration and intensity showed considerable variability (from a single 15-min training session to daily guided meditation sessions for 1 year), with a median of 10 h (as dose of the year-long intervention is problematic to quantify). Just over half of the studies (n = 7) encouraged further practice of techniques outside of the formal training sessions; they made extension activities available for the classroom and recommended teachers integrate techniques into the curriculum, such as pausing during transitions to focus on mindful breathing. Although the majority of interventions were led by teachers (n = 7), they all received prior training that ranged from a full day to an extensive 200-h certification course, with the mean dose of 16 h (2 full days) training. There was a further expectation in two studies that teachers would themselves be practising mindfulness for up to 20 min/day (Jackman et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2020).

Significant outcomes were reported in 10 (83.3%) of the studies. Across the interventions, 26 outcomes were evaluated, of which 17 (65.4%) were significant. Effect sizes ranged from small (n = 7), moderate (n = 1), small to large (n = 2) and large (n = 1). One study did not report sufficient data to calculate this.

Four of the 12 interventions were classified as high efficacy. There was no clear distinction in terms of interventionist (half of the high-efficacy interventions were led by teachers), target (high-efficacy interventions targeted: EF, n = 2; SR, n = 1; or both, n = 1), or dose and duration. In contrast to the previous play-based approaches, relatively more consistent and larger effects were found for global EF, SR and higher-order EF abilities such as planning. Significant and at least moderate effects on more isolated EF abilities, including IC, CF and attention, were relatively infrequent.

Overall, the rate of significance and size of effects suggest this to be an efficacious approach, although in this case higher efficacy was more consistently found in outcomes that required integrated mobilisation of EFs and/or SR.

Social Emotional Learning (SEL) Programs

Eight studies adopted a social-emotional approach to improving children’s EFs (n = 4), SR (n = 2) or EF and SR (n = 2). The average sample size was 296.13, the largest of all the approaches reviewed (range 91–623). Interventions adopting this approach were characterised by their explicit approach to teaching social-emotional skills (two used the CASEL framework; Kats Gold et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020) and their application in the classroom on an ongoing basis. To implement this, studies were teacher led, with one exception (Honoré et al., 2020) was led by an external facilitator in the presence of the class teacher, who was expected to embed new knowledge and skills into the daily practice between sessions. All interventions emphasised the importance of inhibitory control to manage emotions. There were also additional foci that differed by program (e.g. Chicago School Readiness Program), around supporting the teacher to implement consistent practices for behavioural management, nurturing supportive teacher/child relationships, and receptive emotional knowledge (e.g. Kats Gold et al., 2020). The duration of interventions ranged from 6 h over a 6-week period (2 × 30-min sessions a week) to embedding intervention elements across a year.

Six of the studies (75.0%) reported at least one significant outcome, with 23 effects evaluated across all studies (n = 11, or 47.8%, significant). Effect size ranges within each study were reported as small (n = 4), small to moderate (n = 1), small to large (n = 1), moderate to large (n = 1) or large (n = 1).

Four of the 8 interventions were classified as high efficacy, all conducted in 2020. There was no clear distinction between more and less efficacious studies in terms of interventionist (virtually all used teachers). The four most efficacious interventions targeted EFs exclusively, whereas the others all targeted SR in isolation or in conjunction with EF. In contrast to previously profiled approaches, significant and moderate (or better) effect sizes were achieved for IC, albeit for only half of IC outcome measures. Other unique characteristics across these studies were that: three of the four included a meta-cognitive component (whereas none of the less-efficacious interventions did); and all tended to be shorter in duration (ranging from 6 weeks to 6 months, whereas the less efficacious interventions were all 9–12 months in duration).

Overall, the rate of significance and size of effects suggests that interventions adopting a SEL approach, where skills are explicitly taught and practiced regularly in real-life situations there, can be effective for promoting EF including, perhaps, IC.

Curricula & Pedagogy

A total of 3959 participants across 21 studies, adopting a curricular, multi-component or subject-area-embedded approach, are included in this category. These approaches supplemented teacher knowledge and capacity to embed SR/EF training in domain specific contexts.

Curricula

Three different curricula were evaluated across five studies, namely Tools of the Mind, Montessori, and the Intervention Program for Self-Regulation and Executive Functions (PIAFEx). Two interventions had a focus on SR, two on EFs and one on SR and EF combined. These studies had some of the largest sample sizes amongst the approaches considered in this review, ranging from n = 55 to 877 (M = 286.00). The defining characteristic of curricula interventions was the “unifying pedagogy woven across all classroom practices, schedule, environment and activities”, with activities that engage EF in a variety of tasks, situations and contexts (Dias & Seabra, 2015, p.3). In some respects, the longevity of the programs (three lasted a full school year, one for 4.5 months and one for 7 months), combined with the ongoing daily practice of skills across a variety of contexts, make them more of a pedagogical approach than an intervention per se. All curricula intervention studies were led by teachers who had received extensive professional development (e.g. up to 120 h for the Montessori training) to implement the program.

Three of the studies (60.0%) reported at least one significant outcome. Across these studies, 9 effects were evaluated, of which 4 (44.4%) were significant. Effect size ranges for the studies were small (n = 1), small to moderate (n = 1) or large (n = 1). For two studies, effect sizes could not be calculated.

Two of five interventions met criteria as comparatively higher in efficacy evidence. Both had a focus on EF exclusively, whereas the others targeted SR exclusively (n = 2) or in tandem with EF (n = 1). There was little to differentiate high efficacy from other interventions on the basis of dose, duration or interventionist. In an emerging trend, effects were achieved more commonly for attention and CF (as well as global EF, in one study), but not for IC or SR.

Overall, the evidence suggests that curricula focusing on EF can generate measurable and moderate (or better) improvement in certain EFs, although the aggregate evidence is less robust for this approach, and challenges around sustaining fidelity and effects over longer durations remained.

Multicomponent training (Teacher and Child)

Multicomponent interventions (n = 5) targeted SR (n = 2), or EF (n = 2), or SR and EF (n = 1). Sample size averaged 172.80 participants with a range of 53–473. These studies focused on training both the teacher and the child, similar to a curricula approach, but lacked the structured teaching materials of a curriculum. Teacher professional development included training for at least 4 h, with an emphasis on building a theoretical understanding of EF and/or SR and teacher proficiency to lead implementation. This resulted in two intervention strategies: (1) directly intervening with children by teaching SR strategies and/or implementation of activities designed to engage and extend EF/SR; and/or (2) an indirect approach whereby teachers were expected to create ideal conditions to promote SR/EFs, through the intentional creation of high-quality learning environments and positive child-educator relationships. Where child activities were included, their selection, number and timing were suggested rather than prescribed, giving teachers agency to make decisions based on the needs of the children in their class. Intervention dose ranged from 7.5 h across 5 weeks to 9 months with daily practices embedded in all aspects of the preschool day. Teachers were trained by external facilitators, but in all cases, teachers were then tasked with program implementation.

At least one statistically significant outcome was reported for 3 (60.0%) of the 5 studies. Across these studies 13 effects were evaluated, of which four (30.8%) were significant. Effect sizes reported within each study were small (n = 3), small to large (n = 1) or large (n = 1).

Two of the five studies were classified as having greater evidence of high efficacy. There was little clear distinction between these interventions and the others in terms of target, dose, duration or interventionist. What was distinct about these interventions was the professional development for the teacher interventionist. Perels et al. (2009) employed face-to-face, full-group training for 2 h every week for 5 weeks, between sessions teachers would practice their new learnings through prescribed pedagogical ‘assignments’. Walk et al. (2018) employed even more face-to-face training hours, which included time in individual preschools to provide support implementing learning. While other programs also used professional development sessions, these tended to be fewer, shorter and/or online and thereby less bespoke (e.g. able to address specific or emergent questions/issues).

Overall, the current corpus of evidence provides limited support for the overall efficacy of this approach; however, there was some evidence for its potential to generate effects, particularly on global EF, and when more extensive and individuated training was provided to teachers tasked with implementing the intervention.

Music

Interventions in this category (n = 6) targeted EF (n = 5) or SR and EF (n = 1). The studies had an average sample of 77.17 (range 34–160). To be considered ‘musical,’ the program’s activities required musical elements such as pitch and/or the organisation of sound. In addition, five of the six studies (83.3%) included a rhythmical movement element. Average intervention duration was 14.20 h, ranging from 5.3 h (40 min/week over an 8-week period) to 45 h (daily 45-min sessions over 12 weeks). One study (Shen et al., 2019) involved daily practice, whereas three studies held a session once per week. Individual music sessions lasted an average of 40 min, which is longer than typical session times of other approaches. All the interventions in this category were small-group-based, led by external facilitators.

All studies reported at least one outcome that achieved statistical significance. Across the studies 23 effects were evaluated, of which 12 (52.2%) were significant. There was considerable variation in effect sizes reported: small (n = 1); small to moderate (n = 1); small to large (n = 2); moderate to large (n = 1). It was not possible to compute the effect size for one study (Bolduc et al., 2020), due to insufficient data being available.

Four of the six interventions met the requirements for classification as high efficacy. There was little to distinguish between these groups on the basis of interventionist (all external), target (EF-only appeared in both groups), dose and duration. Despite few clear patterns to identify features unique to higher efficacy interventions, two observations were possible. First, this approach had amongst the most consistent (five of seven effects significant) and strongest (moderate or larger effects) effects for IC amongst the approaches evaluated. Second, the study reporting the most efficacious results (four of four effects significant, all moderate or large) uniquely involved daily practice for amongst the longest durations (12 weeks).

Overall, there is moderately strong evidence for the efficacy of this approach to generate EF change, including IC, and these effects may be more pronounced with increased intensity and longevity of music training.

Mathematics

Mathematics interventions (n = 4) — all targeting WM — had an average sample size of 249.25 (median = 56), ranging from 48 to 837. Unique to this approach was the frequent use of multiple intervention arms (e.g. Mathematics only, Mathematics + WM), to determine the specific components that generated an effect, which were then contrasted with a control group. Interventions using Mathematics to improve EF used counting and numeracy games both in whole class and small group contexts. EF-engaging and age-appropriate mathematics activities were structured, such that over the course of the intervention larger numbers were introduced — up to 100. Typical activities were game based, such as “I went to market” and board games that required children to not only count but also remember sequences and rules. Dosage for these four studies varied: one lasted a year with short, daily practice averaging 70 min per week; the remaining three studies were shorter in length, lasting a total of 4–10 h across two 30-–60-min sessions per week for 4 or 5 weeks. Mathematics experts led 75% (n = 3) of the interventions. In the larger study, lasting a full school year (Clements et al., 2020), teachers received extensive PD prior to delivering the program and then ongoing coaching thereafter.

Half (n = 2) of the studies reported at least one significant outcome. Across the studies, 13 effects were evaluated, of which 3 (23.1%) were significant. Effect size ranges for each study were small (n = 2) or large (n = 2).

Two of the four studies were classified as having greater evidence of high efficacy. There was little to differentiate between these studies in terms of target (both classifications had EF-only targets, while the intervention targeting EF and SR was lower in efficacy), dose, duration or interventionist (most led by external facilitator, while the teacher-led program was lower in efficacy). Amongst the higher-efficacy interventions, training was adaptive with feedback at the level of the individual. While this was also the case for Clements et al.’s (2020) large study of 837 children, which was classified as less efficacious, this study used teachers to implement the program and over a more protracted period (a first pilot year, plus a second year given their speculation that it would take more than a year for teachers to master the program to fidelity).

Overall, the aggregate evidence supporting this approach is amongst the weakest profiled in this review, although even here there were large and consistent effects generated by at least some of the programs.

Integrated Arts

One intervention adopted an integrated arts approach to fostering SR. This program was implemented by class teachers, incorporated music, dance and visual arts in the daily schedule to accomplish curricular goals over a 9-month period. The sample, although fairly large (n = 205), was imbalanced with 174 children in the intervention group and only 31 in the control. The study reported a significant outcome on a SR behavioural rating scale and generated an overall moderate effect size for SR.

The uniqueness of this study and limited evidence related to this approach does not allow for identification of common efficacious features. Nevertheless, the high efficacy achieved for SR outcomes is promising.

Non-routine Activities

A total of 2445 participants across 25 studies adopted this approach. In these interventions, educators were asked to do something unlike what they or children would normally do. While physical activity is routine, EF/SR interventions adopting this approach rarely ask children to just engage in routine physical activity. Rather, the physical activity is modified to inject EF/SR challenge into activities, which renders the activity unlike children’s habitual physical activity. Similarly, digitalised training involves computerised training programs that remove children from their routine activity.

Digitalised Task Training

Studies adopting this intervention approach (n = 9) exclusively targeted EF. The average sample size was 154.67 with a range from 49–431. Typically, this approach involved children engaging individually in intensive, structured, adaptive and digital game-based activities for multiple short periods of time during a week (each session lasting between 15 and 60 min). Interventions varied in their dosage and duration (M = 7.50 h), ranging from a total of 1.3 h (1 × 20 min per week, over 4 weeks) to 36 h (4 × 1.5 h a week for 6 weeks). Despite this variability, the majority of studies (n = 7) had a total intervention time of less than 10 h. Although the total number of hours was comparatively low and the intervention period often short, the intensity was high; up to 5 times a week with at least 3 times per week being the most typical convention. Only one intervention was led by the classroom teacher, the remainder (88.9%) were facilitated by external facilitators.

Five studies (55.55%) reported statistical significance for at least one EF outcome. In all, 21 effects were evaluated, of which 7 (33.33%) were significant. Within each study, the effect size range reported was small (n = 1), moderate (n = 1), small to large (n = 1) or moderate to large (n = 1). No effect sizes could be computed for four studies due to insufficient data available, with three of these reporting non-significance for the outcomes evaluated.

Three interventions met criteria as comparatively higher in efficacy evidence. There was little to distinguish these interventions from the others in target (all targeted EF), interventionist (virtually all were external facilitator), dose or duration. In terms of the programs themselves, those characterised as higher in efficacy all involved adaptive training and points-based feedback/motivation, whereas others tended to guide children through set levels of complexity. The only other trend that could be identified in the program features and results was the relatively high rate of success in achieving effects on WM (5 of 6, or 83.3%, significant, often with moderate or larger effects), yet more limited evidence for efficacy on other EFs or global EF.

Overall, given the highly inconsistent evidence in relation to this approach, it may be the case that this approach is particularly suited or tailored to improving WM.

Non-Digitalised Task Training

Corsi Block training was used to enhance WM in four studies, all reported in a manuscript by Gade et al. (2017). Specifically, children were required to reproduce prescribed patterns with increasing complexity using Corsi blocks. All of the studies used external facilitators for implementation. The average sample size was 22.75, ranging from 20 to 31. Intervention periods were comparatively low in total number of hours (up to 3.5 h), but intense (daily practice over 11–12 days). No significant effects were reported for any of the 12 WM outcomes/measures in the studies. Effect sizes were small (n = 2) or small to moderate (n = 2). However, when the data from all four studies was aggregated, the increase in statistical power indicated significant effects of the training. Still, there remains little evidence in support of this approach for generating consistent and sufficient effect on EF and/or SR.

Physical Activity

Studies adopting a ‘cognitively injected’ physical activity approach (n = 12) targeted EF (n = 9) or SR (n = 3). The average sample size was 80.17 (range 30–189). A variety of structured physical activities were included in this category (including some that might not ordinarily be found in a preschool setting), from Street Dancing (Shen et al., 2020), to a gross motor skill intervention (Mulvey et al., 2018), to an Evergaming digital consul (Xiong et al., 2017). Consistent across most of these studies was the inclusion of a cognitive element integrated into group-based physical activities, which often required children to work collaboratively. The exception, in Wen’s study (2018), asked children to individually jump on a mini trampoline for 20 min a day for 10 weeks, with no mediation or added EF/SR challenge. Paralleling the range of activities, the duration and dosage (M = 24.90 h) ranged from a one-off 15-min intervention to 30 min per day for 3 months (150 h). Sessions most often lasted a minimum of 20 min at least 3 times per week (for n = 7 studies). Ten (83.3%) of the interventions were led by external facilitators and two were led by the classroom teacher after 4–8 h of training.

Overall, statistical significance was reported for at least one outcome in 83.33% (n = 10) of the studies. In total, 20 effects were evaluated, of which 14 (70.0%) were significant. The range of effect sizes within each study were as follows: small (n = 3); small to moderate (n = 1); moderate (n = 3); and large (n = 3). For two studies the effect size could not be calculated.

Six of the 12 studies were classified as having greater evidence of high efficacy. Notable is that these studies were diverse in their approach to involving children in cognitively engaging physical activity, from dance to energetic egames to structured motor skill programs. There was little in common that characterised these interventions as distinct from the others, either in terms of target (EF-only and SR-only appeared in both classifications), interventionist (though the two teacher-led interventions were in the less-efficacious category), dose, or duration (most were short sessions for 5–9 weeks). This diversity, however, could be construed as the most prominent pattern amongst these results — diverse approaches to cognitively engaging physical activity yielded significant and moderate or better effects.

This, taken with the strong pattern of significance and the rate/size of significant effects, indicates amongst the strongest support for this approach relative to the others profiled.

Discussion

The current review contributes to the current state of knowledge by bringing together the literature on SR and EF interventions conducted in preschool settings. This is important given increased interest in reconciling the two constructs, and the findings of bi-directional associations between them (Blair, 2016; Blair & Ursache, 2011; Howard et al., 2021a, 2021b). This review is additionally important for highlighting the need for better theory of change for SR and EF, and particularly for their integration. This gap in theoretical grounding exacerbates the wide variability across intervention approaches and complicates clear, unassailable conclusions and recommendations for informing future intervention design, implementation and research.

From a practical perspective, the findings of this review support common and approach-specific mechanisms by which children’s SR/EF is enhanced in the preschool classroom. There is unlikely to be an approach with uniformly high effect for all children and all contexts, so consideration needs to be given to target outcome(s), content and implementation-related mechanisms of change, the context of the intervention and the expertise of the interventionist.

Conclusions drawn from this systematic literature review are, therefore, drawn with an understanding that the approach per se is not the sole (or even primary) determinant of outcomes; different levels of efficacy may be realised by changing any of the ‘what, whom, where, when and how’ of the intervention context. Indeed, it is plausible (perhaps likely) that various vehicles may be suitable for achieving SR and/or EF-promoting conditions. Nevertheless, it is helpful to identify the consistencies amongst studies achieving comparatively more-positive outcomes. Deriving from the reconciliation of studies in this review, several patterns emerged amongst studies achieving more, more consistent and comparatively stronger efficacy results.

Learning Experiences

Cognitive challenge was a feature evident in all the interventions identified as being most efficacious. Uniformly across the approaches reviewed, these interventions would increase EF and/or SR challenge incrementally as children became more familiar with and capable with the intervention activities. This supports previous research (e.g. Diamond & Lee; Holmes et al., 2009; Vygotsky & Cole, 1978) suggesting that EFs grow through appropriate challenge and practice, requiring adjustment upward as child abilities increase. Increasing the cognitive challenge of activities was also evident in approaches that achieved weaker aggregate evidence of efficacy — such as the mediated structured play, adaptive digital training and mathematics — wherein rules changed and parameters were added, adaptive digitalised training and the adaptive methodology adopted in the more effective mathematics studies. Even where there were consistent and robust improvements in the trained abilities in these studies, there was limited evidence that this transferred to the many outcomes that are often sought by SR/EF interventionists (Kassai et al., 2019; Melby-Lervåg & Hulme, 2013; Melby-Lervåg et al., 2016; Sala & Gobet, 2017). It appears reasonable to conclude, therefore, that cognitive challenge on its own is not sufficient to generate EF and SR change (especially of the sort that transfers to other, related abilities and outcomes).

Group Size

Intervention group size is an important consideration for training effectiveness. Studies in this review ranged from whole class interventions (e.g. curricula,) to small groups (e.g. music and creative play) or individualised instruction (e.g. digital). Whilst it may be argued that there are benefits to interventions targeting groups of children, in terms of increased opportunities for social interaction, co-regulation and greater demands on self-regulation, the downside is that the cognitive challenge may not be suitable for everyone working in the group, resulting in unequal training intensity (Marcovitch et al., 2007). In the current results, effects of whole-group curricula training of SR/EF, for example, were small. That said, digital training of individuals, which consumed more resources (in terms of equipment, personnel and time), fared little better. This suggests the possibility that small groups may be an effective means of working with preschool-aged children (see also Scionti et al., 2020). For preschoolers, small groups provide benefits of social interaction, co-regulation and self-regulation, whilst also allowing for greater individuation of cognitive challenge than do whole class approaches.

Movement & Engagement

The inclusion of a movement element, or ‘motor creativity’ (Bugos & DeMarie, 2017), was evident in 53 studies (62.35%). The rate of significance in these studies was high (77.4% of these interventions achieved one or more significant effects) and 23 of the interventions were classified as being highly efficacious (representing 63.88% of all high-efficacy interventions). Movement was an international feature in music, mediated structured play, mindfulness and mathematics interventions. Movement may help to not only consolidate SR/EF gains, through practice and collaborative co-regulation, but may additionally mitigate detrimental factors such as stress (Liston et al., 2009; Schoofs et al., 2009). Furthermore, it has the potential to cultivate a sense of connectedness and social support, as well enjoyment and engagement, which have each been implicated in supporting EF/SR growth (Ahn & Fedewa, 2011; Diamond & Ling, 2016). Even in low-impact activities such as mindfulness, there was suggestion that movement-based activities, such as belly breathing, may have supported children’s focused attention, particularly when used with a prop to help the visualisation (Poehlmann-Tynan et al., 2016). This supports previous research that identified physical activity as being a mechanism to enhance attention (Bidzan-Bluma & Lipowska, 2018; Wood et al., 2020), although perhaps the mechanism of effect is related more to movement, than intensity or amount of activity. However, as with EF/SR challenge, this is likely to interact with other intervention characteristics; multi-component interventions, for instance, also often involved movement, but were unable to achieve the same consistency or strength of results. This may be related to challenges to implementation fidelity, for instance, rather than ineffectiveness of the movement components of these programs. This complexity notwithstanding, the current findings point to this being a beneficial inclusion within the current corpus of studies.

Personnel Leading the Intervention

Perhaps related to the inconsistency in results from interventions involving movement, the current results further suggest that the level of expertise of the personnel leading an intervention is influential. The use of external facilitators, for instance, ensures that the interventionists will be highly trained, experienced and have high self-efficacy and commitment to the fidelity of the intervention (Diamond & Ling, 2016). There is also the potential for ‘novelty effect’, wherein having an unfamiliar person lead the intervention may garner more child attention and engagement (perceived as something ‘special’). Conversely, external facilitators have no prior relationship with the children with whom they are working, and thus differentiating, engaging and sustaining attention in activities will require with, the children.

In the higher efficacious studies led by teachers, a feature common to all was the level of professional development (PD) provided. One of the most efficacious studies reviewed was that by Razza et al. (2015), which required the teacher to complete a 200-hour certificate course in mindfulness yoga prior to implementing the program. This highlights the importance of providing teachers with PD into high-quality practices and supporting their implementation to achieve high fidelity, consistency, mastery and investment in intervention implementation. All studies in this review required teachers to attend some sort of training, usually for a few hours, just prior to the implementation of the program; however, the outcomes were comparatively stronger in studies that spaced out face-to-face training over an extended period (Perels et al., 2009; Walk et al., 2018), providing teachers the opportunity to implement and reflect upon new knowledge, in manageable chunks.

Equally, the ongoing use of coaching to support teachers to embed new practices was seen as a positive feature in several of the effective, longer-term interventions (e.g. Clements et al., 2020; Howard et al., 2020); however, since this was not employed in many studies, nor was it specifically evaluated within the study designs that did, the impact of this inclusion is unclear. Yet anecdotal evidence suggested that coaching may be an important consideration to “build [teacher's] experience and confidence, to become efficacious in his space” (Wu et al., 2020, p.794), and maximise intervention impact as soon as possible. Prior research similarly asserts that efficacy of classroom interventions vary with teachers’ ability to incorporate appropriate strategies to support SR/EF development in their classrooms (Clark, 2010; Little, 2016; Vasseleu et al., 2021), which is often a specific target of coaching. Indeed, teacher knowledge and understanding of how to develop SR and EFs is considered more important than expensive equipment (Tominey & McClelland, 2011). Where teachers can be trained to, or near to, the implementation standard and investment of an external facilitator, teachers would have the advantage of their existing knowledge (of needs) and relationships with the children. As earlier, where this pattern did not hold was for interventions that were comparatively long in duration, such as those embedded across an entire school year.

Dosage

No clear perfect dosage recommendations emerged within or across approaches, however, the opportunity to practise taught skills was evident in the more efficacious studies. This supports prior research indicating the importance of practising targeted abilities (Blair & Raver, 2014; Ericsson & Towne, 2010), and that the best way to enhance these is by performing enjoyable activities in which children are active and involved (Diamond & Ling, 2016; Zosh et al., 2018).

Practice with feedback (either by points scored virtually, or verbally by the interventionist) may be an important key to improving outcomes. Feedback provides opportunity for reflection and metacognition, allowing children the opportunity to reflect upon and adjust their automatic responses. The ability to reflect on, monitor and start to control thoughts and actions, although more rudimentary at the preschool age, has been positioned as an important mediator of SR (Dörr & Perels, 2020; Follmer & Sperling, 2016). That is, children cannot adequately control their behaviour without first some degree of awareness of them (Lyons & Zelazo, 2011; Marulis et al., 2020). A form of (internal) feedback may also be embedded in contemplative practices, such as mindfulness, with its focus on self-awareness, emotional recognition and regulation (Berti and Cigala, 2020; Jackman et al., 2019). This may be supportive in developing a child’s ability to internally reflect in order to monitor, integrate and optimally mobilise EF/SR. The past few years have seen a steady increase in the number of interventions integrating a metacognitive element (7 of 18 studies conducted in the final year searched). This suggests a growing recognition, or at least perception, of its importance for children’s EF/SR development.

Aligning Approach to the Change that is Sought

Results from the reviewed interventions clearly highlight discrepancies in outcomes across the approaches. For instance, results of this review point to some approaches being better suited to developing specific abilities than others. For instance, results imply that mediated structured play may be more suited to developing CF, whereas adopting a music approach may be better suited to enhancing IC.

Moreover, several studies noted that children with the lowest baselines gained most from the intervention (e.g. Gerholm et al., 2019; McClelland et al., 2019; Romero-Lopez et al., 2020; Schmitt et al., 2018; Tominey & McClelland, 2011), paralleling previous findings (Blair & Raver, 2014; Diamond & Ling, 2016). Still other studies noted better outcomes for boys (Kats Gold et al., 2020; Williams & Berthelsen, 2019), for children from higher income families (Thibodeau-Nielsen et al., 2020), or for English Language Learners (Schmitt et al., 2015). While perhaps intuitive, this emphasises the need to align the intervention approach with the target abilities and population, as mechanisms of change likely differ across approaches and intervention characteristics. At present there appears insufficient consideration of how an adopted approach is well suited to growing targeted abilities. Instead, foci are more commonly on characteristics for growth in more global EF/SR ability, acceptability and scalability, minimising dose requirements, and other similar considerations.

Other Implicated Characteristics for Intervention Effectiveness

Indirect Influences

Teachers’ own social and emotional wellbeing is recognised as influencing their capacity in the classroom and impacting their practices (Blewitt et al., 2020; Neuenschwander et al., 2017). Comparatively few interventions targeted teachers’ wellbeing in the current review, although those that did (e.g. Jones et al., 2013; Raver et al., 2011) found that supporting teachers to create positive classroom climates and develop high quality teacher–child relationships not only improved children’s SR/EF, but also teachers' capacity to support their children. Just as a child is better prepared to learn and grow when more-basic needs are met (Bernier et al., 2012; Lawson et al., 2018; Wenzel & Gunnar, 2013), intervention effects and implementation are likely to be improved if children's (and teachers') emotional, social and physical needs are also considered (Diamond, 2013; Diamond & Lee, 2011; Diamond & Ling, 2016) when designing interventions. Broadening the approach to SR/EF development to include a focus on intentionally reducing likely sources of stress for children remains an area requiring further attention, particularly in light of the strong outcomes achieved in the SEL and mindfulness interventions.

Sustainability

Ease of accommodating an intervention within existing preschool routine is a characteristic also warranting further consideration, if change is to be scalable, sustainable and effective. This is particularly important if interventions seek to reduce inequalities of access for children and reduce effects of poverty (Raver et al., 2011). The most widely used approach to deliver intervention ‘training’ was through games. In addition to the mediated structured games, a play-based approach was a feature in many of the identified approaches. This is not surprising given the age of the children involved and the ease with which games may be integrated into daily routines at low cost; both in terms of resources required and teacher training. Furthermore, games can be easily adapted to scale their cognitive challenge. Since games are played in groups, they may also be a vehicle to strengthen skills in teamwork and cooperation through co-regulation. However, small effect sizes reported for the interventions that had an obvious game-based approach (n = 16) suggest that the group context may not provide sufficiently tailored challenge at an individual level. Nevertheless, several studies reported on children’s increased engagement, enjoyment and agency as a by-product of these interventions (Keown et al., 2020; Schmidt et al., 2020). This has implications for children’s levels of joy, stress, connectedness and autonomy, which have been highlighted as influential to EF/SR (Center on the Developing Child, 2016; Diamond & Ling, 2016).

Limitations and Future Directions

For many approaches reviewed, the often-limited number of studies using that approach (and often constrained sample sizes within these studies) means that caution needs to be taken when drawing conclusions about the effectiveness of a particular approach. Non-significant effects might be due to ‘underpowered analyses’, instead of truly no effect (Takacs & Kassai, 2019, p. 691). Furthermore, three of the studies for which an effect size was unable to be computated used a digital approach, and the exclusion of these studies might have may have impacted the overall findings of this approach. However, even with their inclusion, the rate of significance of effects could not have exceeded 50%.

It is also unclear from this review the impact a (lack of) sample diversity had on results. Reporting of demographic characteristics is often not comprehensive or consistent enough to be comparable across studies (e.g. different studies report different selections of indices for, and quantities of, demographics). Considering the demographic data that were available, child backgrounds were not homogeneous, as evidenced by the range of early childhood centres from around the globe, from Head Start services (a U.S.-based program providing for low-income families) to centres linked to universities. While methods such as meta-analyses are well placed to address some of these issues, there were analytic, and study aim considerations that led us to undertake a systematic review. First, meta-analysis is not advised where there is high disparity between studies (i.e. interventions, even within an approach) (Crowther et al., 2010; Garg et al., 2008), as in the current corpus of data. Second, our study aimed to investigate the characteristics of effective EF or SR intervention; while we also were interested in the comparative efficacy of different approaches, aggregating within these would obscure our finding that high efficacy is possible from any of the reviewed approaches (even if this is not the most prevalent outcome for interventions adopting a given approach).

The studies included in this review were not evaluated for fidelity of implementation given this is often unreported and when it is, it is rarely in a common reported form. This is a criteria worth addressing in future studies, given that the fidelity with which any intervention is implemented is likely to affect outcomes. Where this criterion was a consideration, with fidelity checks built into the design and implementation of the study (Lillard, 2012), strong EF outcomes were only achieved by children whose teachers had implemented the Montessori curriculum with a high degree of fidelity.

A number of programs were high in efficacy, yet were also high in burden (e.g. cost, time or resources). Given equivalent effects, we may want to privilege those lower in burden and more easily accommodated into the preschool day. While cost–benefit analysis would require fuller accounts of program requirements that are conventionally reported, the higher efficacy yet lower burden approaches from this review may include physical activities, mediated structured play and mindfulness activities. All of these could be implemented in small groups or whole class, readily integrated throughout the day, and can be delivered by a classroom teacher after relatively brief training. These are important considerations for policy makers who must balance financial investments against return on investment in the form of improved child or educator outcomes.

How long potential gains last, and how well these gains transfer to other outcomes and abilities related to SR/EFs, remains under-evaluated. Only four of the included studies included follow-up assessments several months after the conclusion of the intervention. This is a limitation not only for the current review, but also for SR and EF intervention research more broadly. There is a need for studies to track child outcomes for longer periods, post-intervention, to establish whether acute gains are sustained, or if they ‘fade out’ over time, a phenomenon that is widespread in education interventions (Bailey et al., 2017, 2020). Likewise, the incremental benefits of specific intervention components, characteristics or features is an area of high opportunity for future research.

Conclusions

In sum, our findings lend support to claims that SR and EF abilities can be intentionally enhanced in the preschool years, and that the social, emotional and behavioural contexts of young children’s early educational experiences matter for their opportunities to learn (Blair & Raver, 2014; Center on the Developing Child, 2007, 2012, 2016; Duncan & Magnuson, 2013; McClelland et al., 2015). In line with previous findings, there is neither clear consensus nor evidence for the particular efficacy of one approach over others; all approaches showed some evidence of potential efficacy. This, in and of itself, is one of the core findings of this review; that is, the ‘what, who, for whom, when and how’ an intervention is implemented appears to be more influential than the specific approach. Still, there remain challenges to feasibility and fidelity of implementation in the preschool classroom. Conceptual understanding of SR/EF is not a feature in many preservice teacher training programs. Structural barriers such as attrition, ratios, time and support from leadership constrain opportunities for this learning and mastery. Aside from this, some characteristics of successful programs continue to emerge and further research is required into which, whether and how programs can be scalable and sustainable. Additional longitudinal studies need to be conducted to establish whether, for example, gains achieved following a short, targeted intervention, delivered by a researcher, are sustainable over time. Finally, continued dialogue across education, psychology and health (among others) is required if consensus is to be reached regarding suitable definitions and delineations between EF and SR constructs, to assist and empower teachers to intentionally develop these important abilities in all their children.

References

Ahn, S., & Fedewa, A. L. (2011). A meta-analysis of the relationship between children’s physical activity and mental health. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 36(4), 385–397.

Bailey, D., Duncan, G. J., Odgers, C. L., & Yu, W. (2017). Persistence and fadeout in the impacts of child and adolescent interventions. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 10(1), 7–39.

Bailey, D. H., Duncan, G. J., Cunha, F., Foorman, B. R., & Yeager, D. S. (2020). Persistence and fade-out of educational-intervention effects: Mechanisms and potential solutions. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 21(2), 55–97.

Baron, A., Evangelou, M., Malmberg, L. E., & Melendez-Torres, G. J. (2017). The Tools of the Mind curriculum for improving self-regulation in early childhood: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 13(1), 1–77.

Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., & Tice, D. M. (2007). The strength model of self-control. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(6), 351–355.

Becker, D. R., Miao, A., Duncan, R., & McClelland, M. M. (2014). Behavioral self-regulation and executive function both predict visuomotor skills and early academic achievement. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29(4), 411–424.

Bernier, A., Carlson, S. M., Deschênes, M., & Matte-Gagné, C. (2012). Social factors in the development of early executive functioning: A closer look at the caregiving environment. Developmental Science, 15(1), 12–24.

Berti, S., & Cigala, A. (2020). Mindfulness for preschoolers: Effects on prosocial behavior, self-regulation and perspective taking. Early Education and Development, 33(1), 38–57.

Best, J. R., Miller, P. H., & Naglieri, J. A. (2011). Relations between executive function and academic achievement from ages 5 to 17 in a large, representative national sample. Learning and Individual Differences, 21(4), 327–336.

Bidzan-Bluma, I., & Lipowska, M. (2018). Physical activity and cognitive functioning of children: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(4), 800.