Abstract

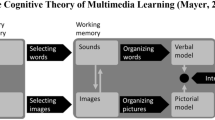

Cognitive models of multimedia learning such as the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning (Mayer 2009) or the Cognitive Load Theory (Sweller 1999) are based on different cognitive models of working memory (e.g., Baddeley 1986) and long-term memory. The current paper describes a working memory model that has recently gained popularity in basic research: the embedded-processes model (Cowan 1999). The embedded-processes model argues that working memory is not a separate cognitive system but is the activated part of long-term memory. A subset of activated long-term memory is assumed to be particularly highlighted and is termed the “focus of attention.” This model thus integrates working memory, long-term memory, and (voluntary and involuntary) attention, and referring to it within multimedia models provides the opportunity to model all these learning-relevant cognitive processes and systems in a unitary way. We make suggestions for incorporating this model into theories of multimedia learning. On this basis, one cannot only reinterpret crucial phenomena in multimedia learning that are attributed to working memory (the split-attention effect, the modality effect, the coherence effect, the signaling effect, the redundancy effect, and the expertise reversal effect) but also derive new predictions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The finding that no modality effect is found with sequential presentation of longer texts and pictures is also in line with the assumption that long auditory texts are disadvantageous because the learner cannot skip back to previous parts of the text (transient information effect; Leahy and Sweller 2011; Wong et al. 2012).

References

Acheson, D. J., & MacDonald, M. C. (2009). Verbal working memory and language production: Common approaches to the serial ordering of verbal information. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 50–68.

Anderson, J. R. (1983). A spreading activation theory of memory. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 22, 261–295.

Atkinson, R. G., & Shiffrin, R. M. (1968). Human memory: A proposed system and its control process. In K. W. Spence & J. T. Spence (Eds.), The psychology of learning and motivation: Advances in research and theory (Vol. 2, pp. 89–195). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Ayres, P., & Sweller, J. (2005). The split-attention principle in multimedia learning. In R. E. Mayer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (pp 135–146). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Baddeley, A. D. (1986). Working memory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Baddeley, A. D. (2000). The episodic buffer: A new component of working memory? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 4, 417–423.

Baddeley, A. D., Hitch, G. J., & Allen, R. J. (2009). Working memory and binding in sentence recall. Journal of Memory and Language, 61, 438–456.

Baddeley, A. D., & Hitch, G. (1974). Working memory. Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 8, 47–89.

Baggett, P., & Ehrenfeucht, A. (1983). Encoding and retaining information in the visuals and verbals of an educational movie. Educational Communication and Technology Journal, 31, 23–32.

Barrouillet, P., Bernardin, S., & Camos, V. (2004). Time constraints and resource-sharing in adults’ working memory spans. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General, 133, 83–100.

Barrouillet, P., & Camos, V. (2012). As time goes by: Temporal constraints in working memory. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21, 413–419.

Boucheix, J.-M., & Lowe, R. K. (2010). An eye tracking comparison of external pointing cues and internal continuous cues in learning with complex animations. Learning and Instruction, 20, 123–135.

Brener, R. (1940). An experimental investigation of memory span. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 26, 467–482.

Chandler, P., & Sweller, J. (1991). Cognitive load theory and the format of instruction. Cognition and Instruction, 8, 293–332.

Colflesh, G. J. H., & Conway, A. R. A. (2007). Individual differences in working memory capacity and divided attention in dichotic listening. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 14, 699–703.

Conway, A. R. A., Cowan, N., & Bunting, M. F. (2001). The cocktail party phenomenon revisited: The importance of working memory capacity. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 8, 331–335.

Courtney, S. M. (2004). Attention and cognitive control as emergent properties of information representation in working memory. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 4, 501–516.

Cowan, N. (1984). On short and long auditory stores. Psychological Bulletin, 96, 341–370.

Cowan, N. (1995). Attention and memory: An integrated framework. Oxford Psychology Series, no. 26. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cowan, N. (1999). An embedded-processes model of working memory. In: A. Miyake, & P. Shah (Eds.). Models of working memory: Mechanisms of active maintenance and executive control. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cowan, N. (2001). The magical number 4 in short-term memory: A reconsideration of mental storage capacity. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 24, 87–185.

Daneman, M., & Carpenter, P. A. (1980). Individual differences in working memory and reading. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 19, 450–466.

De Groot, A. M. B. (1989). Representational aspects of word imageability and word frequency as assessed through word association. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 15, 824–845.

de Koning, B. B., Tabbers, H. K., Rikers, R. M. J. P., & Paas, F. (2009). Towards a framework for attention cueing in instructional animations: Guidelines for research and design. Educational Psychology Review, 21, 113–140.

Dell, G. S., Schwartz, M. F., Martin, N., Saffran, E. M., & Gagnon, D. A. (1997). Lexical access in normal and aphasic speakers. Psychological Review, 104, 801–838.

Dodd, B. J., & Antonenko, P. D. (2012). Use of signaling to integrate desktop virtual reality and online learning management systems. Computers & Education, 59, 1099–1108.

Engle, R. W., & Kane, M. J. (2004). Executive attention, working memory capacity, and a two-factor theory of cognitive control. In B. Ross (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 44, pp. 145–199). New York: Elsevier.

Fürstenberg, A., Rummer, R., & Schweppe, J. (2013). Does visuo-spatial working memory generally contribute to immediate serial letter recall? Does visuo-spatial working memory generally contribute to immediate serial letter recall? Memory, 21, 722–731.

Gyselinck, V., Cornoldi, C., Dubois, V., De Beni, R., & Ehrlich, M. (2002). Visuospatial memory and phonological loop in learning from multimedia. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 16, 665–685.

Hebb, D. O. (1949). The organization of behavior: A neuropsychological theory. New York: Wiley.

Hidi, S. (1990). Interest and its contribution as a mental resource for learning. Review of Educational Research, 60, 549–572.

Iran-Nejad, A. (1987). Cognitive and affective causes of interest and liking. Journal of Educational Psychology, 79, 120–130.

James, W. (1890). Principles of psychology. New York: Holt.

Jeung, H. J., Chandler, P., & Sweller, J. (1997). The role of visual indicators in dual sensory mode instruction. Educational Psychology, 17, 329–343.

Jose, P. E., & Brewer, W. F. (1984). Development of story liking: Character identification, suspense, and outcome resolution. Developmental Psychology, 20, 911–924.

Kalyuga, S. (2011). Cognitive load theory: How many types of load does it really need? Educational Psychology Review, 23, 1–19.

Kalyuga, S., Ayres, P., Chandler, P., & Sweller, J. (2003). The expertise reversal effect. Educational Psychologist, 38, 23–31.

Kalyuga, S., Chandler, P., & Sweller, J. (1999). Managing split-attention and redundancy in multimedia instruction. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 13, 351–371.

Kintsch, W. (1980). Learning from text, levels of comprehension, or: Why anyone would read a story anyway. Poetics, 9, 87–89.

Leahy, W., & Sweller, J. (2011). Cognitive load theory, modality of presentation and the transient information effect. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 25, 943–951.

Lombardi, L., & Potter, M. C. (1992). The regeneration of syntax in short term memory. Journal of Memory and Language, 31, 713–733.

Lowe, R. K. (2004). Interrogation of a dynamic visualization during learning. Learning and Instruction, 14, 257–274.

Lowe, R. K., & Boucheix, J.-M. (2008). Learning from animated diagrams: how are mental models built? In G. Stapleton, J. Howse, & J. Lee (Eds.), Theory and applications of diagrams (pp. 266–281). Berlin: Springer.

Magner, U. I. E., Schwonke, R., Aleven, V., Popescu, O., & Renkl, A. (2013). Triggering situational interest by decorative illustrations both fosters and hinders learning in computer-based learning environments. Learning and Instruction. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2012.07.002.

Majerus, S., Van der Linden, M., Mulder, L., Meulemans, T., & Peters, F. (2004). Verbal short-term memory reflects the sublexical organization of the phonological language network: Evidence from an incidental phonotactic learning paradigm. Journal of Memory and Language, 51, 297–306.

Majerus, S., Attout, L., D’Argembeau, A., Degueldre, C., Fias, W., Maquet, P., et al. (2012). Attention supports verbal short-term memory via competition between dorsal and ventral attention networks. Cerebral Cortex, 22, 1086–1097.

Martin, R. C., Lesch, M. F., & Bartha, M. (1999). Independence of input and output phonology in word processing and short-term memory. Journal of Memory and Language, 41, 2–39.

Martin, N., & Saffran, E. M. (1997). Language and auditory–verbal short-term memory impairments: Evidence for common underlying processes. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 14, 641–682.

Mautone, P. D., & Mayer, R. E. (2001). Signaling as a cognitive guide in multimedia learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93, 377–389.

Mayer, R. E. (2005). Principles for reducing extraneous processing in multimedia learning: Coherence, signaling, redundancy, spatial contiguity, and temporal contiguity principles. In R. E. Mayer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (pp. 183–200). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mayer, R. E. (2009). Multimedia learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mayer, R. E., Griffith, E., Jurkowitz, I. T. N., & Rothman, D. (2008). Increased interestingness of extraneous details in a multimedia science presentation leads to decreased learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 14, 329–339.

Mayer, R. E., Heiser, J., & Lonn, S. (2001). Cognitive constraints on multimedia learning: When presenting more material results in less understanding. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93, 187–198.

Mayer, R. E., & Johnson, C. I. (2008). Revising the redundancy principle in multimedia learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100, 380–386.

Mayer, R. E., & Moreno, R. (1998). A split-attention effect in multimedia learning: Evidence for dual processing systems in working memory. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90, 312–320.

Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological Review, 63, 81–97.

Moreno, R., & Mayer, R. E. (1999). Cognitive principles of multimedia learning: The role of modality and contiguity. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91, 358–368.

Mousavi, S., Low, R., & Sweller, J. (1995). Reducing cognitive load by mixing auditory and visual presentation modes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 87, 319–334.

Oberauer, K., & Kliegl, R. (2006). A formal model of capacity limits in working memory. Journal of Memory and Language, 55, 601–626.

Oksa, A., Kalyuga, S., & Chandler, P. (2010). Expertise reversal effect in using explanatory notes for readers of Shakespearean text. Instructional Science, 38, 217–236.

Paivio, A. (1971). Imagery and verbal processes. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Pashler, H. (1988). Familiarity and visual change detection. Perception & Psychophysics, 44, 369–378.

Penney, C. G. (1989). Modality effects and the structure of short term verbal memory. Memory & Cognition, 17, 398–422.

Popper, K. R. (1935). Logik der Forschung. Wien: J. Springer. [Reprinted as The logic of scientific discovery. London: Hutchinson, 1959.]

Posner, M. I. (1980). Orienting of attention. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 32, 3–25.

Postle, B. R. (2006). Working memory as an emergent property of the mind and brain. Neuroscience, 139, 23–38.

Potter, M. C., & Lombardi, L. (1990). Regeneration in the short-term recall of sentences. Journal of Memory and Language, 29, 633–654.

Potter, M. C., & Lombardi, L. (1998). Syntactic priming in immediate recall of sentences. Journal of Memory and Language, 38, 265–282.

Renkl, A. (2002). Learning from worked-out examples: Instructional explanations supplement self-explanations. Learning and Instruction, 12, 529–556.

Ruchkin, D., Grafman, J., Cameron, K., & Berndt, R. (2003). Working memory retention systems: A state of activated long-term memory. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 26, 709–728.

Rummer, R., Engelkamp, J., & Konieczny, L. (2003). The subordination effect: Evidence from self-paced reading and recall. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 15, 539–566.

Rummer, R., Schweppe, J., Fürstenberg, A., Scheiter, K., & Zindler, A. (2011). The perceptual basis of the modality effect in multimedia learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 17, 159–173.

Rummer, R., Schweppe, J., Fürstenberg, A., Seufert, T., & Brünken, R. (2010). What causes the modality effect in multimedia learning? Testing a specification of the modality assumption. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 24, 164–176.

Sachs, J. S. (1967). Recognition memory for syntactic and semantic aspects of connected discourse. Perception & Psychophysics, 2, 437–442.

Sanchez, C. A., & Wiley, J. (2006). An examination of the seductive details effect in terms of working memory capacity. Memory & Cognition, 34, 344–355.

Schank, R. C. (1979). Interestingness: Controlling influences. Artificial Intelligence, 12, 273–297.

Schnotz, W., Fries, S., & Horz, H. (2009). Motivational aspects of cognitive load theory. In M. Wosnitza, S. A. Karabenick, A. Efklides, & P. Nenniger (Eds.), Contemporary motivation research: From global to local perspectives (pp. 69–96). New York: Hogrefe & Huber.

Schraw, G., & Lehman, S. (2001). Situational interest: A review of the literature and directions for future research. Educational Psychology Review, 13, 23–52.

Schüler, A., Scheiter, K., & van Genuchten, E. (2011). The role of working memory in multimedia instruction: Is working memory working during learning from text and pictures? Educational Psychology Review, 23, 389–411.

Schüler, A., Scheiter, K., Rummer, R., & Gerjets, P. (2012). Explaining the modality effect in multimedia learning: Is it due to a lack of temporal contiguity with written text and pictures? Learning and Instruction, 22, 92–102.

Schweppe, J., & Rummer, R. (2007). Shared representations in language processing and verbal short-term memory: The case of grammatical gender. Journal of Memory and Language, 56, 336–356.

Shipstead, Z., & Broadway, J. M. (2013). Individual differences in working memory capacity and the stroop effect: Do high spans block the words? Learning and Individual Differences, 26, 191–195.

Skuballa, I., Schwonke, R., & Renkl, A. (2012). Learning from narrated animations with different support procedures: Working memory capacity matters. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 26, 840–847.

Sweller, J. (1999). Instruction design in technical areas. Camberwell: ACER.

Sweller, J. (2005). The redundancy principle in multimedia learning. In R. E. Mayer (Ed.), Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (pp. 159–167). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sweller, J. (2010). Element interactivity and intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive load. Educatonal Psychology Review, 22, 123–138.

Sweller, J., Ayres, P., & Kalyuga, S. (2011). Cognitive load theory. New York: Springer.

Sweller, J., & Chandler, P. (1994). Why some material is difficult to learn. Cognition and Instruction, 12, 185–233.

Tabbers, H. K. (2002). The modality of text in multimedia instructions: Refining the design guidelines. Doctoral dissertation, Open University of The Netherlands, Heerlen.

Tabbers, H., Martens, R., & van Merriёnboer, J. J. G. (2004). Multimedia instructions and cognitive load theory: Effects of modality and cueing. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 74, 71–81.

Tiene, D. (2000). Sensory load and information load: Examining the effects of timing on multisensory processing. International Journal of Instructional Media, 27, 183–199.

Todd, J. J., Fougnie, D., & Marois, R. (2005). Visual short-term memory load suppresses temporo-parietal junction activity and induces inattentional blindness. Psychological Science, 16, 965–972.

Todd, J. J., & Marois, R. (2004). Capacity limit of visual short-term memory in human posterior parietal cortex. Nature, 428, 751–754.

Turner, M. L., & Engle, R. W. (1989). Is working memory capacity task dependent? Journal of Memory and Language, 28, 127–154.

Walker, I., & Hulme, C. (1999). Concrete words are easier to recall than abstract words: Evidence for a semantic contribution to short-term serial recall. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 25, 1256–1271.

Watkins, O. C., & Watkins, M. J. (1977). Serial recall and the modality effect: Effects of word frequency. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory, 3, 712–718.

Wong, A., Leahy, W., Marcus, N., & Sweller, J. (2012). Cognitive load theory, the transient information effect and e-learning. Learning and Instruction, 22, 449–457.

Yue, C. L., Bjork, E. L., & Bjork, R. A. (2013). Reducing verbal redundancy in multimedia learning: An undesired desirable difficulty? Journal of Educational Psychology, 105, 266–277.

Zimmer, H. D. (2008). Visual and spatial working memory: From boxes to networks. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 32, 1373–1395.

Zimmer, H. D., & Fu, X. (2008). Working memory capacity and culture–based expertise. Paper presented at the XXIV International Congress of Psychology, Berlin.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schweppe, J., Rummer, R. Attention, Working Memory, and Long-Term Memory in Multimedia Learning: An Integrated Perspective Based on Process Models of Working Memory. Educ Psychol Rev 26, 285–306 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-013-9242-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-013-9242-2