Abstract

The present study investigated if preschool children’s intention understanding could predict their use of other-oriented conflict resolution strategies. Participants were 30 preschool children (13 girls, Mage = 4.46 years, SD = 0.73, range: 3.21–5.50 years). The children were observed for their conflict resolution strategies during freeplay at school for one 30-min session per day on three separate days. Conflict resolution strategies were coded into two broad categories: “self-oriented strategies” that did not recognize the opponents’ needs and wants, and “other-oriented strategies” that took into account others’ perspectives. To assess children’s understanding of intentions, children were presented with three sets of story pairs adapted from Astington and Lee’s (What do children know about intentional causation? Paper presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Seattle, WA, 1991) study. After controlling for age and language ability, children with more robust understandings of intentions tended to utilize greater percentages of other-oriented resolution strategies during peer conflicts. Implications for how early childhood educators can support young children’s understanding of intentions and conflict resolution behaviors are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Astington, J. W. (1991). Intention in the child’s theory of mind. In D. Frye & C. Moore (Eds.), Children’s theories of mind (pp. 157–172). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Astington, J. W. (1993). The child’s discovery of the mind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Astington, J. W., & Lee, E. (1991). What do children know about intentional causation? Paper presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Seattle, WA

Baird, J. A., & Astington, J. W. (2005). The development of the intention concept: From the observable world to the unobservable mind. In R. R. Hassin, J. S. Uleman, & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), The new unconscious (pp. 256–276). New York: Oxford University Press Inc.

Baumgartner, E., & Strayer, F. F. (2008). Beyond flight or fight: Developmental changes in young children’s coping with peer conflict. Acta Ethologica,11(1), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10211-007-0037-7.

Chen, D. W. (2003). Preventing violence by promoting the development of competent conflict resolution skills: Exploring roles and responsibilities. Early Childhood Education Journal,30(4), 203–207. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023379306124.

Chen, D. W., Fein, G. G., & Tam, H.-P. (1998). Teacher interventions in the conflicts of preschool children: Effects of children’s age and conflict behavior. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Diego, CA

Chen, D. W., Fein, G. G., Killen, M., & Tam, H.-P. (2001). Peer conflicts of preschool children: Issues, resolution, incidence, and age-related patterns. Early Education and Development,12(4), 523–544. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15566935eed1204_3.

Dawe, H. C. (1934). An analysis of two hundred quarrels of preschool children. Child Development,5, 139–157. https://doi.org/10.2307/1125449.

Dunn, L. M., & Dunn, L. M. (1997). Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test—Third Edition (PPVT-III). Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

Eisenberg, A. R., & Garvey, C. (1981). Children’s use of verbal strategies in resolving conflicts. Discourse Processes,4, 149–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/01638538109544512.

Feinfield, K. A., Lee, P. P., Flavell, E. R., Green, F. L., & Flavell, J. H. (1999). Young children’s understanding of intention. Cognitive Development,14, 463–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-2014(99)00015-5.

Flavell, J. H. (2000). Development of children’s knowledge about the mental world. International Journal of Behavioral Development,24(1), 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/016502500383421.

Hartup, W. W., Laursen, B., Stewart, M. I., & Eastenson, A. (1988). Conflict and the friendship relations of young children. Child Development,59, 1590–1600.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (1996). Conflict resolution and peer mediation programs in elementary and secondary schools: A review of the research. Review of Education Research,66(4), 459–506. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543066004459.

Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics,33(1), 159–174. https://doi.org/10.2307/2529310.

Laursen, B., & Hartup, W. W. (1989). The dynamics of preschool children’s conflicts. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly,35(3), 281–297.

Laursen, B., Finkelstein, B. D., & Betts, N. T. (2001). A developmental meta-analysis of peer conflict resolution. Developmental Review,21(4), 43–449. https://doi.org/10.1006/drev.2000.0531.

Lillard, A. S., & Flavell, J. H. (1992). Young children’s understanding of different mental states. Developmental Psychology,28(4), 626–634. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.28.4.626.

Maynard, D. W. (1985). How children start conflicts. Language in Society,14(1), 1–29.

Moore, C., & Frye, D. (1991). The acquisition and utility of theories of mind. In D. Frye & C. Moore (Eds.), Children’s theories of mind (pp. 1–14). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Mull, M. S., & Evans, E. M. (2010). Did she mean to do it? Acquiring a folk theory of intentionality. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology,107, 207–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2010.04.001.

Olson, D. R., Astington, J. W., & Harris, P. L. (1988). Introduction. In D. R. Olson, J. W. Astington, & P. L. Harris (Eds.), Developing theories of mind (pp. 1–18). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Putallaz, M., & Sheppard, B. H. (1992). Conflict management and social competence. In C. Shantz & W. Hartup (Eds.), Conflict in child and adolescent development (pp. 330–355). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ross, H., & Conant, C. (1992). The social structure of early conflict: Interaction, relationships, and alliances. In C. U. Shantz & W. W. Hartup (Eds.), Conflict in child and adolescent development (pp. 153–187). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Schult, C. A. (2002). Children’s understanding of the distinction between intentions and desires. Child Development,73(6), 1727–1747. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00502.

Selman, R. L., Schorin, M. Z., Stone, C. R., & Phelps, E. (1983). A naturalistic study of children’s social understanding. Developmental Psychology,19(1), 82–102. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.19.1.82.

Shantz, C. U., & Hartup, W. W. (1992). Conflict resolution in child and adolescent development. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Shultz, T. R., & Wells, D. (1985). Judging the intentionality of action-outcomes. Developmental Psychology,21, 83–89. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.21.1.83.

Shultz, T. R., Wells, D., & Sarda, M. (1980). Development of the ability to distinguish intended actions from mistakes, reflexes, and passive movements. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology,19, 301–310. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1980.tb00357.x.

Spivak, A. L. (2016). Dynamics of young children’s socially adaptive resolutions of peer conflict. Social Development,25(1), 212–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12135.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A

Observation Coding Guide

A conflict begins after an initial opposition. That is, if Child A tries to influence Child B, Child B’s verbal or physical opposition (e.g., disagreeing, correcting, accusing, insulting, challenging, or ignoring Person A’s request) initiates a conflict episode. Child A or B can be the target child.

Once a conflict episode begins, all of the target child’s verbal and nonverbal turns can be coded as self- or other-oriented strategies.

Conflicts end when one speaker’s oppositional turn no longer elicits an oppositional turn from the other or when a teacher intervenes.

Self-Oriented Strategies

The target children’s verbal or physical tactics that only purport their own goals with little consideration of the opponents' goals during a conflict.

Other-Oriented Strategies

The strategies that coordinate both the target children’s and opponents' viewpoints.

Appendix B

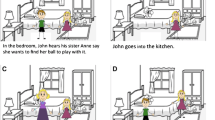

Intention Story Set #1

Intentional

Emily sees Jane drawing with a crayon at the table. Emily walks over to Jane.

Emily grabs Jane’s crayon and puts it in her backpack.

The crayon is in Emily’s backpack.

Unintentional

Olivia sees Sally drawing with a crayon at the table. Olivia walks over to Sally.

Olivia bumps into the table. Sally’s crayon rolls into Olivia’s backpack.

The crayon is in Olivia’s backpack.

Test Question:

Which girl, Emily or Jane, planned to have a crayon in her backpack?

Intention Story Set #2

Intentional

Madeline is gathering up all the books from the bookshelf. Allison is sitting on the rug.

Madeline walks towards the rug and gives Allison a book.

Allison now has a book to read.

Unintentional

Wendy is gathering up all the books from the bookshelf. Jackie is sitting on the rug.

Wendy walks towards the rug and a book drops behind her.

Jackie now has a book to read.

Test Question:

Which girl, Madeline or Wendy, planned for the other girl to have a book to read?

Intention Story Set #3

Intentional

Abby is sitting next to Natalie. Both are eating lunch at the lunch table.

Abby picks up her cup of water. Abby pours the water onto Natalie.

Natalie is now all wet.

Unintentional

Jessica is sitting next to Kelly. Both are eating lunch at the lunch table.

Jessica picks up her cup of water. The cup slips out of out of Jessica’s hands and lands on Kelly.

Kelly is now all wet.

Test Question:

Which girl, Abby or Jessica, planned for the other girl to get wet?

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pieng, P., Okamoto, Y. Examining Preschool Children’s Intention Understanding and Their Conflict Resolution Strategies. Early Childhood Educ J 48, 597–606 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-020-01020-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-020-01020-0