Abstract

Background and Aims

Conventional adenomas (CAs) and serrated polyps (SPs) are precursors to colorectal cancer (CRC). Understanding metachronous cancer risk is poor due to lack of accurate large-volume datasets. We outline the use of natural language processing (NLP) in forming the Partners Colonoscopy Cohort, an integrated longitudinal cohort of patients undergoing colonoscopies.

Methods

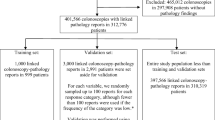

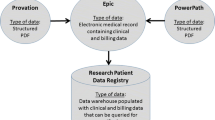

We identified endoscopy quality data from endoscopy reports for colonoscopies performed from 2007 to 2018 in a large integrated healthcare system, Mass General Brigham). Through modification of an established NLP pipeline, we extracted histopathological data (polyp location, histology and dysplasia) from corresponding pathology reports. Pathology and endoscopy data were merged by polyp location using a four-stage algorithm. NLP and merging procedures were validated by manual review of 500 pathology reports.

Results

305,656 colonoscopies in 213,924 patients were identified. After merging, 76,137 patients had matched polyp data for 334,750 polyps. CAs and SPs were present in 86,707 (28.5%) and 55,373 (18.2%) colonoscopies. Among patients with polyps at index screening colonoscopy, 14,931 (33.4%) had follow-up colonoscopy (median 46.4, interquartile range 33.8–62.4 months); 91 (0.2%) and 1127 (2.5%) patients developed metachronous CRC and high-risk polyps (polyps ≥ 10 mm or CAs having high-grade dysplasia/villous/tublovillous histology or SPs with dysplasia). Genetic data were available for 23,787 (31.7%) patients with polyps from the Partners Biobank. The validation study showed a positive predictive value of 100% for polyp histology and locations.

Conclusion

We created the Partners Colonoscopy Cohort providing essential infrastructure for future studies to better understand the natural history of CRC and improve screening and post-polypectomy strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, et al. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int J Cancer. 2019;144(8):1941–1953.

Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, et al. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.002.

Joseph DA, Meester RGS, Zauber AG, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: estimated future colonoscopy need and current volume and capacity. Cancer. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30070.

Zauber AG, Winawer SJ, O’Brien MJ, et al. Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths. New Engl J Med. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1100370.

Zauber AG, Winawer SJ, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, van Ballegooijen M, O’Brien MJ. Effect of initial polypectomy versus surveillance polypectomy on colorectal cancer mortality reduction: micro-simulation modeling of the national polyp study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007. https://doi.org/10.14309/00000434-200709002-01207.

Schroy PC, Wong JB, O’Brien MJ, Chen CA, Griffith JL. A risk prediction index for advanced colorectal neoplasia at screening colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2015.146.

Gupta S, Jacobs ET, Baron JA, et al. Risk stratification of individuals with low-risk colorectal adenomas using clinical characteristics: a pooled analysis. Gut. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310196.

Toyota M, Ahuja N, Ohe-Toyota M, Herman JG, Baylin SB, Issa JPJ. CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.96.15.8681.

Spring KJ, Zhao ZZ, Karamatic R, et al. High prevalence of sessile serrated adenomas with BRAF mutations: a prospective study of patients undergoing colonoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2006. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.038.

Powell SM, Zilz N, Beazer-Barclay Y, et al. APC mutations occur early during colorectal tumorigenesis. Nature. 1992. https://doi.org/10.1038/359235a0.

Atkin WS, Cuzick J, Morson BC. Long-term risk of colorectal cancer after excision of rectosigmoid adenomas. New Engl J Med. 1992. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199203053261002.

Click B, Pinsky PF, Hickey T, Doroudi M, Schoen RE. Association of colonoscopy adenoma findings with long-term colorectal cancer incidence. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.5809.

Gupta S, Lieberman D, Anderson JC, et al. Recommendations for follow-up after colonoscopy and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2019.10.026.

Weinberg DS, Schoen RE. Preneoplastic colorectal polyps: “I found them and removed them-now what?” Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:667–668

Crockett SD, Nagtegaal I. Terminology, molecular features, epidemiology, and management of serrated colorectal neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(4):949–966.

Fernando WC, Miranda MS, Worthley DL, et al. The CIMP phenotype in BRAF mutant serrated polyps from a prospective colonoscopy patient cohort. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/374926.

Carr NJ, Mahajan H, Tan KL, Hawkins NJ, Ward RL. Serrated and non-serrated polyps of the colorectum: their prevalence in an unselected case series and correlation of BRAF mutation analysis with the diagnosis of sessile serrated adenoma. J Clin Pathol. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.2008.061960.

Ijspeert JEG, Vermeulen L, Meijer GA, Dekker E. Serrated neoplasia-role in colorectal carcinogenesis and clinical implications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:401–409

Tinmouth J, Henry P, Hsieh E, et al. Sessile serrated polyps at screening colonoscopy: have they been under diagnosed? Am J Gastroenterol. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2014.78.

Niv Y. Changing pathological diagnosis from hyperplastic polyp to sessile serrated adenoma: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29:1327–1331

Vogelstein B, Fearon ER, Hamilton SR, et al. Genetic alterations during colorectal-tumor development. New Engl J Med. 1988. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198809013190901.

Morin PJ, Sparks AB, Korinek V, et al. Activation of β-catenin-Tcf signaling in colon cancer by mutations in β-catenin or APC. Science. 1997. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.275.5307.1787.

Nayor J, Borges LF, Goryachev S, Gainer VS, Saltzman JR. Natural language processing accurately calculates adenoma and sessile serrated polyp detection rates. Dig Dis Sci. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-018-5078-4.

Nalichowski R, Keogh D, Chueh HC, Murphy SN. Calculating the benefits of a research patient data repository. In: AMIA ... Annual symposium proceedings/AMIA symposium. AMIA symposium. 2006.

Outcomes O of DM and. Massachusetts Cancer Registry. Mass.gov. 2020. https://www.mass.gov/massachusetts-cancer-registry. Accessed 22 May 2020

Karlson EW, Boutin NT, Hoffnagle AG, Allen NL. Building the partners healthcare biobank at partners personalized medicine: Informed consent, return of research results, recruitment lessons and operational considerations. J Personal Med. 2016. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm6010002.

Greene MA, Butterly LF, Goodrich M, et al. Matching colonoscopy and pathology data in population-based registries: development of a novel algorithm and the initial experience of the New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2011.03.1250.

Anderson JC, Butterly LF, Goodrich M, Robinson CM, Weiss JE. Differences in detection rates of adenomas and serrated polyps in screening versus surveillance colonoscopies, based on the New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2013.04.042.

Álvarez C, Andreu M, Castells A, et al. Relationship of colonoscopy-detected serrated polyps with synchronous advanced neoplasia in average-risk individuals. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2013.03.003.

Kahi CJ, Hewett DG, Norton DL, Eckert GJ, Rex DK. Prevalence and variable detection of proximal colon serrated polyps during screening colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2010.09.013.

Hetzel JT, Huang CS, Coukos JA, et al. Variation in the detection of serrated polyps in an average risk colorectal cancer screening cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2010.315.

Payne SR, Church TR, Wandell M, et al. Endoscopic detection of proximal serrated lesions and pathologic identification of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps vary on the basis of center. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2013.11.034.

Li D, Woolfrey J, Jiang SF, et al. Diagnosis and predictors of sessile serrated adenoma after educational training in a large, community-based, integrated healthcare setting. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2017.08.012.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the gastroenterology and histopathology staff at Partner's Healthcare.

Funding

This work received on external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to conception and design. MV and MS undertook analysis and interpretation of the data and drafting of the article. SG, JN, MS undertook critical revision of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vithayathil, M., Smith, S., Goryachev, S. et al. Development of a Large Colonoscopy-Based Longitudinal Cohort for Integrated Research of Colorectal Cancer: Partners Colonoscopy Cohort. Dig Dis Sci 67, 473–480 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-021-06882-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-021-06882-x