Abstract

The nature and direction of criminology has changed significantly over the past two decades. The subject area has also grown exponentially and become more diverse. New fields of inquiry are opening up as new issues are added to the criminological agenda. However, at the same time there are some unwelcome developments in the discipline that impact on the orientation of the subject and which detract from its overall viability and standing. The aim of this paper is to identify these unwelcome trends in order to contribute to the development of a more critical and coherent criminology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Academic criminology has grown rapidly over the last two or three decades in many parts of the world. There are an increasing number of students taking newly designed courses offering a wide range of specialisms. There has also been a proliferation of journals, books, articles and conferences. In this process, new areas of investigation have been opened up, particularly in relation to the cultural and environmental aspects of crime and justice as well as a welcome focus on different forms of oppression, suffering, discrimination and injustice. This has resulted in an overall enrichment and diversification of the subject as a result of which traditional disciplinary boundaries have been eroded or redrawn. Indeed, it has been one of the strengths of academic criminology over the years that as a sub-discipline within the social science it has been able to draw freely on a range of other social science disciplines.

In this context, we could just stand back and admire the wealth of material that is being produced, the number of students being taught, careers being developed as well as the new knowledges that are emerging. And if we just wanted a quick measure on the current state of health of criminology we could point to the remarkable number and range of publications. Needless to say, this growing criminological industry is producing a considerable amount of interesting and informative work some of which is highly original. But there are some developments that are taking place in the subject area that detract in varying degrees from the overall quality and value of the work that is produced. The aim of this paper is to identify some of these less positive trends in order to contribute to the development of a more critical and coherent criminology.

The Demise of Theory

Criminologists in the 1960s and 1970s tended to identify with a particular theoretical tradition. Many saw themselves, for better or worse, as symbolic interactionists, labelling theorists, control theorists, Marxists, sub cultural theorists or strain theorists. The contributions of Howard Becker, Alvin Gouldner, Erving Goffman, Cloward and Ohlin, David Matza amongst others played a major role in shaping and constructing modern criminology during this period. As Garland and Sparks (2000: 197) have argued the 1970s was in many respects a watershed in the development of criminology and it was a period in which criminologists became more ‘reflexive, more critical and more theoretical’. The publication of Taylor, Walton and Young’s The New Criminology (1973) and Critical Criminology (1975) Richard Quinney’s The Social Reality of Crime (1970), Stuart Hall et al. Policing the Crisis (1978) Carol Smart’s Women and Crime and Criminology (1976), Thomas Mathieson’s The Politics of Abolition (1974) James Q. Wilson’s Thinking About Crime (1975) and most notably Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish (1977) were amongst a substantial body of powerful publications that challenged the intellectual, institutional and political assumptions of traditional criminology. These publications individually and collectively changed the way in which crime and punishment were conceived amongst the criminological community and they have remained important points of reference over the last four decades.

Even during the ascendancy of conservative criminology in the 1980s and early 1990s attempts were made to articulate theories of cognitive development, personality formation as well as outlining the social conditions for the production of deviant subjects (Wilson 1991; Wilson and Herrnstein 1985). Herrnstein and Murray’s The Bell Curve (1994) is reported to have been the best-selling criminology book of this period despite—or maybe as a result of—its biosocial focus (see Lilly et al. 2011).

During the 1980s there were also some landmark texts produced by more radical authors. Stanley Cohen’s authoritative Visions of Social Control (1985) and John Braithwaite’s Crime, Shame and Reintegration (1989) as well as Cullen and Gilbert’s Reaffirming Rehabilitation (1982) and Lea and Young’s What is to be Done About Law and Order? (1984) all provided a radical reassessment of crime and punishment as a response, on one hand, to the growing disillusionment amongst criminologists about the possibility of progressive reform and to what was seen as the growing impact of the Right both politically and intellectually, on the other.

However, since the mid 1990s there have been very few major theoretical criminological publications and some of the most widely referenced texts, it is suggested, have made a limited contribution to our understanding. Indeed, it is indicative that over the past two decades that criminology has increasingly imported materials from related disciplines, particularly sociology and social philosophy. It is writers like David Harvey, Nancy Fraser, Mike Davis, Zygmunt Bauman, Ulrich Beck, Elijah Anderson, William Julius Wilson, Pierre Bourdieu and the like who have become familiar reference points in criminology and have been used to inject some theoretical substance into a subject area that has become theoretically light. The significant aspect of this development is that whereas criminological texts in the 1960s and 1970s were in many cases embedded in social theory the varieties of social theory that appear in the contemporary criminological literature tend to be imported.

If we accept for the moment that this is the case, the question arises of why has there been a decline in substantial theoretical contributions despite the proliferation of publications. I suggest that there are four main reasons why this occurring. First, there is a growing pressure to produce publications amongst academics and the growth of the subject area has made it an increasingly competitive. Second, that there is a growing emphasis on providing vocational courses and focusing on the employability of graduates. This has led to an increased emphasis on the acquisition of skills and a decreasing interest in theoretical issues. Third, that criminological theory is often taught as a discreet set of ideas which are associated with the distant past and whose relevance to current issues is unclear. Consequently, students have a limited interest in the art of theorising. Fourth, and slightly more controversially, the ascendancy of varieties of liberal criminology in the 1990s has changed the theoretical orientation in criminology away from wide ranging structural accounts to more selective issues associated with the defence of liberal values.

There can be little doubt that we now live in ‘publish or perish world’. This is the case in most, if not all, academic disciplines but is particularly pronounced in criminology, because of the growing number of people entering the field and the pressures on securing employment, gaining promotion and increasing one’s marketability. Thirty of forty years ago these pressures were less evident and while it was seen as beneficial for those who did publish it is now seen as essential. Even newly appointed academic criminologists are expected in most universities to have some publications. Once on the academic treadmill, expectations increase and those who fail to publish regularly are likely to be sidelined. In this context having the time and space to engage in serious theoretical work becomes something of a luxury. For the majority of aspiring criminologists, publications and research activities have to be churned out on a regular basis, often in between heavy teaching and administrative loads. This can lead to the well-established practice of recycling the same material.

There is a growing concern amongst students in relation to future employment. For them the job market has become more competitive and many are aware that even well qualified students can find it difficult to find suitable employment after graduation. Universities are also becoming more sensitive to this issue by setting up employment advisors and creating links with prospective employers. At the same time universities are modifying their courses to provide more vocational training. The implication is that criminology becomes more distant from its sociological and theoretical roots and more emphasis is placed on learning particular and transferable skills.

Many criminology courses in the 1960s and 1970s were part of a more general social science degree, but as more specialised, professionalised and vocational courses have appeared criminology has become increasingly disembedded from other social science disciplines and their different theoretical contributions (Savelsberg and Sampson 2002). Moreover, outside of North America and Britain the new courses in criminology that have developed over the last twenty or thirty years are often located in law departments which has a different relationship to theory—particularly those universities that focus on black letter law. In these institutions, the established cannons of sociological and criminological theory are less familiar and there is likely to be less interest in developing these theoretical approaches.

We tend to spend a great deal of time providing methodology courses and training students in a variety of methodological techniques. However, we spend considerably less time in teaching them to theorise (Swedberg 2016). Instead, we tend to assume that theorising is a matter of intuition. Moreover, in most academic institutions there is a disconnect between theory, method and practice. Criminological theory tends to be compartmentalised and seen as largely outdated body of historical materials, rather than being presented as a living and inspiring resource (see Hall and Winlow 2012).

Consequently, over the last two decades or so a growing body of criminologists appear not to be linked to any overarching body of theoretical knowledge. The demise of theory and the lack of substantial problematics has resulted in many criminologists building careers around certain ‘topics’ whose selection appears to be largely arbitrary and contingent. It is often difficult not only to identify what these contributions stand for and how they fit in the order of things, but also what they stand against.

If the 1980s was dominated by forms of conservative criminology the subsequent period has seen the ascendancy of varieties of liberalism. What is significant about this shift is that liberalism is essentially a political programme aimed at eliminating specific social and political evils rather than constructing a universalising social or political theory (Shklar 1977). The main focus is on human freedom, individualism and the fear of arbitrary power. It expresses a deep hostility to autocracy as well as a cultural distaste for conservatism and tradition (Bell 2014; Guess 2002). Thus, its aim is not so much to provide a unified body of theory but rather to defend or promote liberal values.

Under the influence of liberalism, the focus has shifted in criminology to what is seen as the development of more punitive and authoritarian system of social control. In this context, it is felt that there has been erosion of liberal ideals and the main objective the seen to be the reduction of state power, developing more benign and informal methods of crime control and in general to restrict what is viewed as the unnecessary overreach of social control. As Alan Ryan (2012) concludes in his examination of modern liberalism:

The liberalism that has triumphed, is not an intellectually rigorous system, manifested in its only possible institutional form. It is an awkward and intellectually insecure system committed to democracy tempered by the rule of law, to a private enterprise economy supervised and controlled by government, and to equal opportunity so far as it can be maintained without too much interference with the liberty of employers, schools and families. (Ryan 2012: 41).

In a similar vein, Mills (1959) claims that liberal sociology lacks of appreciation of the structural conditions of social life and the need to change them. He suggests that they tend to engage in low-level theoretical explanations of social processes ‘detached from any tenable theory of society of any effective means of action’. Liberals, he argues lack a political programme, which is adequate to the moral ideas that it professes and consequently ends up by inadvertently providing a defence of the status quo. The suggestion is that the increasing dominance of liberal criminology over the past two decades has shifted the theoretical emphasis towards a narrower and more selective modes of theorising bound up with the expression or defence of liberal values.

If we accept that we have witnessed the demise and realignment of criminological theory over the past two decades this is not to suggest that there is not some interesting theoretical work taking place. We have seen some useful theoretical discussions taking place under the banner of cultural criminology (Ferrell et al. 2008; Hayward and Young 2012; O’Brien 2005; Matthews (2014a) and green criminology (South and Brisman 2014; Stretesky et al. 2014). Feminist criminologies have become more prolific and diverse. They have challenged to apparent universality of much ‘malestream’ criminology while placing issues of gender centre stage (Leonard 1983; Smart 1990; Renzetti 2013) We have also witnessed the proliferation of texts on racial disadvantage and discrimination, particularly in America (Sudbury 2005; Western 2006; Bowling and Phillips 2002). There has been some stimulating and thoughtful work taking place in relation to the issues of desistance and rehabilitation (Maruna 2000; Ward and Maruna 2007). There has been some provocative discussion around Foucauldian themes (Rose 1999; Garland 1997) as well as an informative examination of the application of risk analysis within the criminal justice system (O’Malley 2004; Hannah-Moffat 2001). However, probably the most significant theoretical development in the recent period has been linked to the development of Southern Theory, the import of which has been to fundamentally challenge any claims to universality by the traditional theoretical approaches associated with the global North. One of the paradoxes of globalisation is that we are becoming increasingly aware of the different conceptions of crime, justice and forms of legality operating in different locations, and in particular the lack of ‘fit’ between the criminological realities of the ‘North’ and the ‘South’ (Connell 2007; Carrington et al. 2016).

Political and Cultural Reductionism

Among those contemporary criminologists who do try to develop theoretical accounts there is a noticeable tendency to engage in forms of political reductionism. This accounts to a large extent the uncanny preoccupation amongst a substantial body of liberal criminologists with the so-called ‘new punitiveness’, on one hand, and the perceived impact of neoliberalism in shaping crime control policies, on the other (Garland 2001; Pratt 2007; Green 2009; Indermaur 2009; Simon 2001; Wacquant 2008). Although both these accounts in themselves arguably provide seriously deficient explanations of the changing nature of crime control they have been widely adopted as ready-made, easy-to-use accounts which readily connect with liberal sensibilities.

The initial mobilisation of the notion of punitiveness was associated with the attempts to explain the development of mass incarceration in America and in particular the adoption of what was seen as tougher forms of mandatory and indeterminate sentencing. In addition, the introduction of boot camps, three strikes legislation, zero tolerance policing and antisocial behaviour orders were seen to provide examples of populist punitiveness. The surge in punitiveness, it was argued, was fuelled by avaricious politicians who wanted to be seen to be talking tough on crime and an anxious public who were presented as being increasingly intolerant. The problem with this account is that it imputed motives and values to both politicians and the general public that did not match up with the messy social reality that has emerged over the past two decades (see Matthews 2005). In fact, the evidence shows that over this period policymakers and politicians on both sides of the Atlantic have become more reticent about expanding the prison estate, while some States in America have actually reduced prison numbers or closed down prisons over the last decade or so. (Porter 2012) Zero tolerance policing and mandatory sentencing statutes have been largely disbanded, while research on public opinion suggests that the general public are deeply ambivalent about the use of prison and other forms of punishment (Cullen et al. 2002; Doble 2002).

Public opinion surveys also indicate that the issue of crime has slipped down the list of public concerns, while crime control and ‘law and order’ have hardly featured in the last two Presidential elections in America and recent Parliamentary elections in the UK (Jacobson 2006; Mauer 2002). The real failure of the punitiveness thesis, however, is that it provides a simple mono-causal account of the development of crime control and has directed attention away from the development of a more coherent and credible explanation of the actual changes that are taking place. As Tonry (2007:1) has argued ‘if penal populism or populist punitiveness exists at all it is mostly as reifications in academics’ minds of other academics ideas’.

In a similar vein the resort to neoliberalism as the ‘root cause’ of crime control policies is at best limited and at worst misguided. The rise of neoliberalism is repeatedly presented as the principle or sole determinant of some of the major changes that have taken place in recent years including prison expansion, welfare state contraction, and the changing nature of crime control (Reiner 2007; Wacquant 2009).

Wacquant (2009) is one of the more outspoken advocates of accounts based on the rise of neoliberalism. He claims that neoliberalism lies behind the expansion of the prison system and a simultaneous shift from the welfare state to the workfare state (Peck 2010). As with the notion of punitiveness this form of hydraulic functionalism appeals to those who want an uncomplicated explanation of events.

There are a number of problems with this account. First, the links between, neoliberalism and its supposed effects are asserted rather than clearly demonstrated. Second, and relatedly, the apparent ‘symbiotic’ relationship between the decline of the Keynesian welfare state and the growth of the penal state is highly speculative and unproven. Third, as Lacey (2013) has pointed out the neoliberalism thesis has failed to explicate just what political and social institutions constitute neoliberalism and by implication what neoliberalism ‘is’, how it emerged, and what sort of institutional structures are needed to sustain its policies and practices. Consequently, she argues that as an explanatory thesis it is deeply flawed:

The conceptual vagueness of neoliberalism, and the institutional deficit that characterizes the neoliberal penality thesis, dooms it to failure as an explanatory account of contemporary punishment. Historical and comparative examples comprehensively undermine the idea that ‘neoliberalism’ is plausible as an explanation of current trends in punishment, striking as it may be as a characterization of a certain kind of political reaction to a constellation of current geo-political and economic conditions. The neo-liberal thesis should, therefore, be abandoned (Lacey 2013: 277)

Moreover, during the Thatcher era in the 1980s, which is arguably the high point of neoliberalism in the UK, police budgets were slashed and fewer people were sent to prison annually in England and Wales at the end of the Thatcher era than they were at the beginning (see Pitts 2013). In particular, there was a significant decrease in the number of juveniles and young people sent to prison. Similar developments have been associated with the current neoliberal regime in Britain with the 25 per cent decrease in police funding with a consequent reduction of 20,000 uniformed police officers. At the same time the number of prison officers in UK has been cut by 30 per cent (Dodd 2015). Even in America there is an issue about the timing of the rise of neoliberalism and changing forms of crime control, which raises questions about the causal relations between the two.

We can see a similar kind of reductionism associated with the development of cultural criminology. Although there is a negative capitalist ethos that runs through much of this work (Ferrell et al. 2008; Presdee 2000) one of its leading proponents claims that: ‘Capitalism is essentially cultural these days’ and that ‘economics are decisively cultural in nature” (Ferrell 2007:92-3). While there is no doubt, the cultural criminology has made an important contribution and enriched criminological investigation it is necessary to examine the relation between the economic and the cultural rather than subsuming the former within the latter (Hall and Winlow 2007). Cultural accounts can best offer partial explanations of why people think and behave as they do (Kuper 1999), and the lack of engagement with the changing dynamics of contemporary capitalism and replacing these with struggles over the’transposition of images’ is inadequate (Ferrell et al. 2008: 199). It is not enough just to blame capitalism. The task is to produce a cultural political economy, or a form of ‘cultural realism’ that avoids reductionism (see Matthews 2014b). It is not that political and cultural determinants are not important, they are. But there are invariably other determinants, including political economy, that interact with these processes in a variety of different ways.

The Retreat from Causality

In everyday life we are preoccupied with trying to work out how and why things happen and, in particular, to identify the causal connections between events. It seems, however, that in recent years many criminologists have become less and less concerned with providing causal explanations. We have also seen amongst administrative criminologists a reluctance to engage in ‘deep causes’ and instead focus on the more immediate and proximate causes that might be associated with crime. Amongst social reaction theorists on the other hand, there is little or no interest in the causes of crime, while traditional causal explanations based on poverty and deprivation have fallen into disfavour, particularly since the ‘crime drop’, which has taken place over the past two decades, seems largely impervious to changing levels of poverty and deprivation (see Karman 2000; Parker 2008; Currie 2016; Ignatans and Matthews 2017; Matthews 2016). As Young (2011) pointed out many of the explanations of the crime drop move almost imperceptivity from correlations to causation and much of this work is surprisingly inconclusive.

At the same time, there is a preoccupation amongst a large body of criminologists with statistical analysis on the assumption that presenting issues of crime and punishment in these terms makes their analysis more ‘scientific’ rigorous and objective (Young 2004). However, many of the issues with which criminologists are concerned—motivation, values, attitudes and other context-dependent activities—do not lend themselves easily to quantification. Consequently, these mathematical approaches provide a limited understanding of these issues and are essentially acausal. Even regression analyses, which are sometimes treated as indicating causal connections, say nothing in themselves about causal mechanisms or relations (Manicas 2006).

Those who engage in the search for correlations are persistently faced with the problem of whether associations are causal or coincidental. The examination of the effects of ‘independent’ variables on ‘dependent’ variables can at best only identify quantifiable change but not causes. In many cases the accounts need to be supplemented by qualitative analysis in order to find out which causal mechanisms are in play. As Sayer (2000) has argued from a critical realist perspective, what causes something to happen has nothing to do with a number of times we have observed it happening. Explanations, he suggests, depend instead on ‘identifying the causal mechanisms and how they work, and discovering if they have been activated and under what conditions’.

In response to the perceived deficiencies of statistical analysis there has been a growing interest in recent years in the development of forms of qualitative analysis in an attempt to engage more directly with the lived reality of the subjects under study and how they construct their social worlds. Consequently, different strands of qualitative analysis have become more widely used. However, although providing a deeper sense of how individuals and groups give meaning to their lives and activities much of this work is descriptive and lacks causal analysis. However, as Hammersley (1992) has argued the aim of a good ethnography is to identify the causal relations involved and to discern patterns and processes that provide a degree of generalisability. The retreat from causal explanations, particularly ‘deep’ structural causes together with the tendency for writers to assert rather than explain the connections between different processes reduces explanatory capacity. Similarly, the preoccupation with narrow descriptive accounts, which lack generalisability, provide, at best, partial explanations. In these cases the inability to identify the causal mechanisms in play means that the probability of developing a response or solution to the issues under investigation is likely to be limited.

The identification of causal processes, however, is far from straightforward. There are often complex and contradictory causes that require serious and systematic investigation. However, an understanding of causal processes is a crucial component for criminologists who want to move beyond pure description and the appreciation of the subjects under study and are interested in developing convincing explanations that engage with policy options.

The Erosion of Social Class

References to social class amongst criminologists have become very unfashionable. Whereas conservative criminologists make reference to a loosely defined notion of the underclass, liberals prefer to talk in terms of the poor the marginalised and the disadvantaged (Herrnstein and Murray 1996; Western 2006). Where social class is referred to it is often conceived of in terms of income or educational level rather than seeing it in relation to the process of production (Pettit and Western 2004). The significance of social class, however, is that it remains a moral signifier in everyday life and in the criminal justice system in particular. Class position continues to shape people’s sense of identity, their interests, life opportunities, as well as their views on crime and justice. (Skeggs 2004; Sayer 2005).

It seems a long time ago since criminologists like Richard Quinney (1977) and John Hagan (1992) argued for the necessity of placing class analysis in the centre of criminological investigation. More recently, however, the dominant view seems to be either that historically constructed conceptions of social class are no longer valid, or alternatively that the question of crime and punishment are no longer reducible to issues of class (Pettit and Western 2004).

This is unfortunate since the historical construction of the problem of crime and punishment as Foucault (1977) has convincingly argued involves, in essence, a conflict between a respectable working class and the so-called underclass. As Foucault and others have pointed out the prison is almost exclusively reserved for the underclass. Prisons in America and other countries may house a disproportionate number of people drawn from ethnic minorities, but there are as many black or Hispanic middle-class professionals in prison as white middle-class professionals. That is, virtually none.

By the same token the police are by and large drawn from the ranks of the respectable working class, while the judiciary are drawn disproportionally from the upper classes in most countries. In short, the whole of the criminal justice system is structured along class lines while crime itself as realists pointed out some years ago is essentially intra-class rather than inter-class, with victims being drawn disproportionally for the most vulnerable sections of society (Young 1988).

Foucault’s powerful thesis on disciplinary power and imprisonment argues that the function of the modern prison is to ‘grind rogues honest’ through labour discipline and at the same to reduce and redistribute illegalities. However, although the direct object of punishment is the ‘criminal classes’ they provide, he suggests, a manageable and ultimately disposable population that can be recycled through the criminal justice system and serve as a constant reminder to the respectable working class of the dangers of nonconformity. The clear message of Disciple and Punish, which seems to have been overlooked by many, is that by creating and focusing on a system of ‘enclosed illegalities’, the illegalities perpetuated by the upper classes are obscured and sidelined. Thus, for Foucault the whole structure of the modern criminal justice system is based on a form of class conflict exercised through the development of new forms of power relations. Consequently:

The question of the prison cannot be resolved or even posed in terms of a simple penal theory. Neither can it be posed in terms of a psychology or sociology of crime. The question of the role and possible disappearance of the prison can only be posed in terms of an economy and a politics, that is, a political economy of illegalisms (Foucault 2009: 13).

To see the racial disproportionally in prisons as predominantly or exclusively a function of racial discrimination, as Michelle Alexander claims in her best selling The New Jim Crow (2010), is to over-racialise the process of incarceration. Virtually all the African Americans who are incarcerated are drawn disproportionately from the same social class. There is also a conspicuous lack of recognition of the high rate of Hispanics incarcerated in America, who are of course drawn from the same social class. The disproportionate focus on a black-white in North American criminology division presents a peculiarly monochromatic vision in what must be one of the most multi-racial societies in the world. This is not to deny racism, which of course is important, but overlooking the class dynamics not only serves to obscure the functions of crime control but also can inadvertently reinforce the notion that ‘law and order’ is little more than an expression of racial prejudice.

There has recently been a concerted attempt to link class, gender and race in an attempt to move beyond an essentialist gender perspective in order to develop an approach to identity-based politics that draws attention to the simultaneous and interactive forms of oppression and disadvantage. While this approach formally broadens the scope of inquiry and includes some consideration of social class it has been beset by both conceptual and methodological difficulties (Burgess-Proctor 2006).

The theoretical concerns stem from some uncertainty about whether the key terms of ‘race’, ‘gender’ and ‘class’ are fixed or fluid categories whether the analysis of inequalities involves the addition of discrete forms of inequality and oppression or whether these forms of inequality are mutually shaping. Critics have questioned the assumed sameness and equivalence of the categories connected to inequality and the mechanisms and process that constitute them (Nash 2008; Verloo 2006). There are also unresolved questions about the relation between structural and political inequalities. Armstrong et al. (2012) have, for example, pointed out that in the early debates about gender inequality there was interest in the interaction between gender and class relations, but this interest has faded. Consequently, much debate on intersectionality has been primarily concerned with issues of gender and race.

Moreover, although the focus on intersectionality has drawn attention to the overlapping and compounding effects of different forms of oppression, not all forms of oppression are the same. Class, for example is not a product of prejudice. The poor are not clamouring for poverty to be legitimised and valued. Instead, they want to escape or abolish class positions, not to affirm them. Reducing class to a form of prejudice goes some way to legitimising class differences. As Sayer (2005) has pointed out:

[Thus] there are both similarities and differences between ‘class’ and ‘race’, for example. Interaction between people in both cases expresses fear, distrust, contempt, disgust, loathing, derision and a sense of inferiority and superiority, but class differences would exist even in the absence of these responses, whereas the inequalities of ‘race’ are fundamentally dependent on them. Were it not for the popularity of cultural reductionism in which all differences are treated as products of cultural representations, it would not be necessary to state the obvious: racism is a necessary condition for the reproduction of ‘race’, but ‘class-ism’ is not a necessary condition for the reproduction of class (Sayer 2005: 94).

Pierre Bourdieu (1977, 1987) has pointed out that constructing and maintaining notions of class has not only an economic but also social, cultural and emotional dimensions. His analysis allows us to analyse interactions between different sources of inequality and goes beyond seeing class as the culmination of different ‘variables’. He has made a major contribution to our understanding of the subjective experiences of class and argues that the struggle for recognition relies not only on the demands for recognition but also requires having the resources to live and act in ways that deserve recognition. Thus, recognition is unlikely to be achieved simply through improved communication and signification, but requires the mobilisation of material goods (Fraser 1999).

Growing Scepticism About Crime and Victimisation

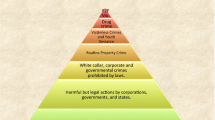

There is a growing scepticism about the significance of crime and criminal victimisation amongst criminologists that goes back at least as far as the classic article by Luke Hulsman (1986) on critical criminology in which he argued that crime has no ontological integrity. Hulsman argued that the notion of ‘crime’ lacks consistency and that it is, in fact, a relatively arbitrary social construction. This line of argument has been revived in recent years by Hillyard et al. (2004), who have argued that the’myth of crime’ needs to be replaced or supplemented by broader social harm perspective. However, as Hillyard et al. (2004) note ‘harm’ is no more definable than ‘crime’ and it too lacks ontological integrity. However, while broadening the focus on social suffering which is in itself commendable there is a danger of shifting attention away from the day to day operation of the criminal justice system and the victims of crime. This social harm perspective is often presented in opposition to ‘normal’ or ‘street’ crime but there is no formal contradiction. Normal crime is a form of harm and there are considerable overlaps between those who are victims of crime and those that are victims of other social harms. The critical question are why certain forms of harm become defined as crime in certain periods.

The growth of green criminology also represents something of a move away from normal or street crime, although some of its adherents do focus on aspects of corporate and state crime. This wide-ranging and diverse perspective has raised important questions about the environment and the erosion of human resources and in doing so has tended to shift the focus from a focus on the individual or group nature of criminal victimisation to the notion of the collective victim. That is, most of humanity are apparently in line to become victims of environmental developments, whether we are aware of it or not (Halsey 2004; White and Hackenberg 2014). Some green criminologists, on the other hand, have changed their focus from human to non-human victims (Beirne and South 2013). In the process of exploring this new terrain, however, the millions of people who are victims of interpersonal violence, robbery and theft are left some way behind.

As Zedner (2011) has pointed out despite the expansion of the criminological industry in recent years, it is striking how little contemporary criminological scholarship deals with normal crime, and that in so far as criminology engages with crime it tends to do so negatively. That is, crime tends to be presented as a signifier of institutional failure. In particular, she argues the social harm perspective fails to address the fundamental issues of moral agency, wrongdoing and blameworthiness that lie at the heart of the criminal law.

Probably the most significant example of the neglect of the issue crime is the paucity of criminological interest, particularly in the UK, of the crime drop. Although the decrease in recorded crime in a number of western countries is undoubtedly the most significant criminological development in living memory criminologists have been slow to engage with this issue. There are also some criminologists who want to deny the crime drop has in fact taken place and point to the unreliability of crime data, while others claim that crime has not really decreased, because of the significant increase in cybercrime (Matthews 2016; Wall 2007). However, the fact that significant decreases in crime has been recorded in at least twelve countries, while cybercrime involves a different group of offenders and victims than traditional forms of crime, suggests that a major change has in fact taken place (McGuire 2016). At the same time most of the explanations of the crime drop that have been presented are less than convincing and tend to involve mono-causal accounts. Farrell (2013) has identified five tests that he claims any viable hypothesis should meet if it is to provide an adequate explanation of the crime drop. These include (1) whether the theory explains international variations, (2) whether the theory is consistent and plausible, (3) whether the theory compatible with previous accounts of the increase in crime (4) whether it accounts for variations in changing levels of different crime types and (5) whether the theory compatible with trajectory of crime falls between different countries. He concludes that fourteen of the fifteen theories that he examined failed two or more tests.

Looking at the other side of the coin there is also deep-seated ambivalence towards victims of crime, particularly amongst social reaction theorists and social constructionists. If you believe the crime is just a function social reaction that it is fairly arbitrary construction there is likely to be little interest in the plight of victims. Although there has been a growing interest in the plight of the victim in public and policy circles in recent years liberal criminologists like Garland (2001: 143) tend to be sceptical of this development seeing the construction of ‘the victim’ as a measure adopted by elected officials to increase their legitimacy and as a ‘justification for measures of penal repression’. Simon (2009) adopts a similar line of argument claiming that the state has used crime and victimisation as vehicles for extending the range and depth of control into more and more areas of private life. Thus, for example, Simon argues that the state has made unnecessary incursions into domestic life by criminalising domestic violence, the implication is that we need to return to the era in which domestic violence was a ‘private’ matter which would of course undo the years of struggle that have taken place to protect and defend these victims. Significantly, Simon, is not particularly interested in suggesting better ways to protect the victims of domestic violence by changing legislation or by other means, but instead his main interest is limiting state intervention.

While many feminists would take issue with Simon’s thesis on the treatment of victims of domestic violence there is also some reticence towards identifying women as victims by some feminists who claim that attributing the victim label to women treats them as passive and lacking agency (Lamb 1999; Pease 2007). It is the case, however, that defining oneself as a victim is an important step towards redress and self-protection. Not to identify oneself as a victim is to accept injury or loss and offer the offender impunity.

It should be remembered that the growing focus on the victim over the last thirty or forty years is not a result of pressure from the Right. Rather, the increased interest in the victim and the development of the victim movement has been achieved historically by combination of critical, feminist and realist criminologists who themselves have been part of a wider struggle for social justice. In addition, the focus on victims has provided the basis for the development of more informal and restorative modes of adjudication that are widely seen as providing a more constructive and progressive response to a variety of transgressions, rather than operating within the traditional offender-centred criminal justice system.

Conclusion

Over the past two decades the composition and orientation of criminology has changed significantly. During this period, we have seen as shift away from the dominance of conservative criminology, which with all its limitations did place crime and punishment at the top of its agenda and was very successful in affecting policy and practice. Ericson and Carriere (1994; 96–97) have argued that criminology has become more fragmented and claimed with some justification that this fragmentation ‘can be viewed as indicative of the collapse of the conservative orthodoxies which were previously more successful in imposing a relatively monolithic order on the field’. Although there are continuing signs of fragmentation and diversification there are also discernable realignments taking place in criminology as well as various trends that are impacting on the value of the work produced.

However, the time has come to move away from the liberal-conservative orthodoxy that has dominated criminology for the last four decades and go beyond what Cullen et al. (2011) refers to as ‘adolescent-limited criminology’ and what Elliott Currie (2007) calls ‘So What?’ criminology and engage in a form of ‘joined up‘criminology that is theoretically informed, favours explanations over description, causal analysis over assertions, avoids reductionism and aims to take crime and crime victims seriously.

References

Alexander, M. (2010). The new jim Crow. New York: The New York Press.

Armstrong, S., Walby, J., & Strid, S. (2012). Intersectionality; multiple inequalities in social theory. Sociology, 46(2), 224–240.

Beirne, P., & South, N. (2013). Animal rights, animal abuse and green criminology. In P. Beirne & N. South (Eds.), Issues in green criminology: Confronting harms against environments, humanity and other animals. London: Routledge.

Bell, D. (2014). What is liberalism? Political Theory, 42(6), 682–715.

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1987). What makes a class? On the theoretical and practical existence of groups. Berkeley Journal of Sociology, 32, 1–17.

Bowling, B., & Phillips, C. (2002). Racism, crime and justice. Harlow: Longman.

Burgess-Proctor, A. (2006). Intersections of race, class, gender and crime: Future directions for feminist criminology. Feminist Criminology, 1(1), 27–47.

Carrington, K., Hogg, R., & Sozzo, M. (2016). Southern criminology. British Journal of Criminology, 56(1), 1–20.

Cohen, S. (1985). Visions of social control. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Connell, R. (2007). Southern theory. Cambridge: Polity.

Cullen, F., & Gilbert, K. (1982). Reaffirming rehabilitation. Cincinnati: Anderson.

Cullen, R., Lilly, F., & Ball, R. (2011). Criminological theory: Context and consequences (5th ed.). California: Sage.

Cullen, F., Pealer, B., Fisher, B., Applegate, B., & Santana, S. (2002). Public support for correctional rehabilitation in America; change or consistency. In J. Roberts & M. Hough (Eds.), Changing attitudes to punishment. Willan: Cullompton.

Currie, E. (2007). Against marginality; arguments for a public criminology. Theoretical Criminology, 11(2), 175–190.

Currie, E. (2016). The violence divide: Taking “Ordinary” crime seriously in a volatile world. In R. Matthews (Ed.), What is to be done about crime and punishment?. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Doble, J. (2002). Attitudes to punishment in the US—Punitive and liberal opinions. In J. Roberts & M. Hough (Eds.), Changing attitudes to punishment. Willan: Cullompton.

Dodd, V. (2015). West midlands to reduce the number of officers on the beat. 16th March.

Ericson, R., & Carriere, K. (1994). The fragmentation of criminology. In D. Nelken (Ed.), The futures of criminology. London: Sage.

Farrell, G. (2013). Five tests for a theory of the crime drop. Crime Science, 2(1), 1–23.

Ferrell, J. (2007). For a ruthless cultural criticism of everything existing. Crime Media Culture, 3(1), 91–100.

Ferrell, J., Hayward, K., & Young, J. (2008). Cultural criminology. London: Sage.

Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. London: Allen Lane.

Foucault, M. (2009). Alternatives to the prison: Dissemination or decline of social control? Theory, Culture and Society, 26(6), 12–24.

Fraser, N. (1999). Social justice in the age of identity politics; redistribution, recognition and participation. In L. Ray & A. Sayer (Eds.), Culture and economy after the cultural turn. London: Sage.

Garland, D. (1997). Governmentality and the problem of crime: Foucault, criminology, sociology. Theoretical Criminology, 1(2), 173–214.

Garland, D. (2001). The culture of control. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Garland, D., & Sparks, R. (2000). ‘Criminology, social theory and the challenge of our times’. British Journal of Criminology, 40, 189–204.

Green, D. (2009). Feeding wolves: Punitiveness and culture. European Journal of Criminology, 6(6), 517–536.

Guess, R. (2002). Liberalism and its discontents. Political Theory, 30(3), 320–338.

Hagan, J. (1992). ‘The poverty of a classless criminology’—The American Society of Criminology 1991 Presidential Address. Criminology, 30(1), 1–20.

Hall, S., Critcher, C., Jefferson, T., Clarke, J., & Roberts, B. (1978). Policing the crisis. London: MacMillan.

Hall, S., & Winlow, S. (2007). Cultural Criminology and primitive accumulation: A formal introduction to two strangers who should really become more intimate. Crime Media Culture, 3(1), 82–90.

Hall, S., & Winlow, S. (2012). The need for new directions in criminological theory. In S. Hall & S. Winlow (Eds.), New directions in criminological theory. London: Routledge.

Halsey, M. (2004). Against ‘green. Criminology’ British Journal of Criminology, 44, 833–853.

Hammersley, M. (1992). What is wrong with ethnography?. London: Routledge.

Hannah-Moffat, K. (2001). Moral agent or actuarial subject: Risk and Canadian women’s imprisonment. Theoretical Criminology, 3(1), 71–94.

Hayward, K. (2015). Cultural criminology: Script rewrites. Theoretical Criminology, 20(3), 1–25.

Hayward, K., & Young, J. (2012). Cultural Criminology. In M. Maguire, R. Morgan, & R. Reiner (Eds.), The oxford handbook of criminology (5th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Herrnstein, R., & Murray, C. (1996). The bell curve. New York: Free Press.

Hillyard, P., Pantazis, C., & Tombs, S. (2004). Beyond criminology: Taking harm seriously. London: Pluto Press.

Hulsman, L. (1986). Critical criminology and the concept of crime. Contemporary Crisis, 10(1), 63–80.

Ignatans D and Matthews R (2017) ‘Immigration and the crime drop’. European Journal of Crime Law and Criminal Justice, 295–329.

Indermaur, D. (2009). What can we do to engender a more rational and less punitive crime policy? European Journal of Criminal Policy Research, 15, 181–199.

Jacobson, M. (2006). Reversing the punitive turn: The limits and promise of current of current research. Criminology and Public Policy, 5(2), 277–284.

Karman, A. (2000). New York murder mystery. New York: New York University Press.

Kuper, A. (1999). Culture: The anthropologists account. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Lacey, N. (2013). Punishment, (Neo) liberalism and social democracy. In J. Simon & R. Sparks (Eds.), The sage handbook of punishment and society. London: Sage.

Lamb, S. (1999). New versions of victims: Feminist struggle with the concept. New York: New York University Press.

Lea, J. (1998). Posfordism and criminality. In N. Jewson & S. McGregor (Eds.), Transforming cities: Contested governance and new spatial divisions. New York: Routledge.

Lea, J., & Young, J. (1984). What is to be done about law and order?. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Leonard, E. (1983). Women, crime and society. London: Longman.

Lilly, J., Cullen, F., & Ball, R. (2011). Criminological theory: Contexts and consequences. Los Angeles: Sage.

Manicas, P. (2006). A realist philosophy of social science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Maruna, S. (2000). Making good: How ex-convicts reform and rebuild their lives. Washington: American Psychological Association.

Matthews, R. (2005). The myth of punitiveness. Theoretical Criminology., 9(2), 175–201.

Matthews, R. (2014a). Realist criminology. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Matthews, R. (2014b). Cultural realism? Crime Media Culture, 10(3), 203–214.

Matthews, R. (2016). Realist criminology, the new aetiological crisis and the crime drop. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, 5(3), 1–10.

Mauer, M. (2002). ‘State sentencing reforms: Is the “get tough” era coming to an end? Federal Sentencing Report, 15(1), 50–52.

McGuire, M. (2016). Cybercrime 4.0: Now what is to be done? In R. Matthews (Ed.), What is to be done about crime and punishment?. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mills, C. W. (1959). The sociological imagination. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nash, J. (2008). Re-thinking intersectionality. Feminist Review, 89, 1–15.

O’Brien, M. (2005). What is cultural about cultural criminology? British Journal of Criminology, 45, 599–612.

O’Malley, P. (2004). Risk, uncertainty and government. London: Glasshouse Press.

Parker, K. (2008). Unequal crime decline: Theorizing race, urban inequality and criminal violence. New York: New York University Press.

Pease, K. (2007). Victims and victimisation. In S. Shoham, O. Beck, & M. Kent (Eds.), International handbook of penology and criminal justice. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Peck, J. (2010). Zombie neoliberalism and the ambidextrous state. Theoretical Criminology, 14(1), 104–110.

Pettit, B., & Western, B. (2004). Mass imprisonment and the life-course: race and class inequality in U.S. incarceration. American Sociological Review, 69, 151–169.

Pitts, J. (2013). The third time as farce: What ever happened to the penal state? In P. Squires & J. Lea (Eds.), Criminalisation ad advanced marginality: Critically exploring the work of loic wacquant. Bristol: Policy Press.

Porter, N. (2012). On the chopping block 2012: State prison closings. Washington D C: The Sentencing Project.

Pratt, J. (2007). Penal populism. London: Routledge.

Presdee, M. (2000). Cultural criminology and the carnival of crime. London: Routledge.

Quinney, R. (1970). The social reality of crime. Boston: Little Brown.

Quinney, R. (1977). Class state and crime. New York: Longman.

Reiner, R. (2007). Law and order: An honest citizen’s guide to crime and control. Cambridge: Polity.

Renzetti, C. (2013). Feminist criminology. London: Routledge.

Rose, N. (1999). Government and control. British Journal of Criminology, 40(2), 324–339.

Ryan, A. (2012). The making of modern liberalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Savelsberg, J., & Sampson, R. (2002). Mutual engagement: Criminology and sociology? Crime, Law and Social Change, 37, 99–105.

Sayer, A. (2000). Realism and social science. London: Sage.

Sayer, A. (2005). The moral significance of class. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shklar, J. (1977). Rethinking the past. Social Research, 44(1), 80–90.

Simon, J. (2001). Entitlement to cruelty: Neo-liberalism and the punitive mentality in the United States. In K. Stenson & R. Sullivan (Eds.), Crime, risk and justice. Willan: Cullompton.

Simon, J. (2009). Governing through crime. New York: Oxford University Press.

Skeggs, B. (2004). Class, self, culture. London: Routledge.

Smart, C. (1990). Feminist approaches to criminology or postmodern woman meets atavistic man. In L. Gelsthorpe & A. Morris (Eds.), Feminist perspectives in criminology. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

South, N., & Brisman, A. (2014). Routledge international handbook of green criminology. London: Routledge.

Stretesky, P., Long, M., & Lynch, M. (2014). The treadmill of crime: Political economy and green criminology. London: Routledge.

Sudbury, J. (2005). Global lockdown: Race, gender and the prison-industrial complex. New York: Routledge.

Swedberg, R. (2016). Before theory comes theorizing or how to make social science more interesting. The British Journal of Sociology, 67(1), 5–22.

Taylor, I., Walton, P., & Young, J. (1973). The new criminology. London: Routledge.

Taylor, I., Walton, P., & Young, J. (1975). Critical criminology. London: Routledge.

Tonry, M. (2007). Determinants of penal policy. In M. Tonry (Ed.), Crime and justice: An annual review of research (Vol. 35). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Verloo, M. (2006). Multiple inequalities, intersectionality and the European Union. Journal of Women’s Studies, 13(3), 211–228.

Wacquant, L. (2008). Ordering insecurity: Social polarization and the punitive upsurge. Radical Philosophy Review, 11(1), 9–27.

Wacquant, L. (2009). Punishing the poor: The neoliberal government of social insecurity. North Carolina: Duke University Press.

Wall, D. (2007). Cybercrime: The transformation of crime in the information age. Cambridge: Polity.

Ward, T., & Maruna, S. (2007). Rehabilitation. London: Routledge.

Western, B. (2006). Punishment and inequality in America. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

White, R., & Hackenberg, D. (2014). Green criminology; an introduction to the study of environmental harm. Abingdon: Routledge.

Wilson, J. Q. (1975). Thinking about crime. New York: Basic Books.

Wilson, J. Q. (1991). On character: Essays. Washington: American Enterprise Institute.

Wilson, J. Q., & Herrnstein, R. (1985). Crime and human nature. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Wilson, J., & Kelling, G. (1982). The police and neighbourhood safety: broken windows’. Atlantic Monthly, 127, 29–38.

Young, J. (1988). Risk of crime and fear of crime: the politics of victimisation studies. In M. Maguire & J. Pointing (Eds.), Victims of crime: A new deal?. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Young, J. (2004). Voodoo criminology and the numbers game. In J. Ferrell, K. Hayward, W. Morrison, & M. Presdee (Eds.), Cultural criminology unleashed. London: Glasshouse Press.

Young, J. (2011). The criminological imagination. Cambridge: Polity.

Zedner, L. (2011). Putting crime back on the criminological agenda. In M. Bosworth & C. Hoyle (Eds.), What is criminology?. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Matthews, R. False Starts, Wrong Turns and Dead Ends: Reflections on Recent Developments in Criminology. Crit Crim 25, 577–591 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10612-017-9372-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10612-017-9372-9