Abstract

Rates of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors (SITBs) increase sharply across adolescence and remain high in young adulthood. Across 50 years of research, existing interventions for SITBs remain ineffective and inaccessible for many young people in particular need of mental healthcare. Briefer intervention options may increase access to care. However, many traditional interventions for SITBs take 6 months or more to complete—making it difficult for providers to target SITBs under real-world time constraints. The present review (1) identifies and (2) summarizes evaluations of brief psychosocial interventions for SITBs in young people, ages 10–24 years. We conducted searches for randomized and quasi-experimental trials conducted in the past 50 years that evaluated effects of “brief interventions” (i.e., not exceeding 240 min, or four 60-min sessions in total length) on SITBs in young people. Twenty-six articles were identified for inclusion, yielding a total of 23 brief interventions. Across all trials, results are mixed; only six interventions reported any positive intervention effect on at least one SITB outcome, and only one intervention was identified as “probably efficacious” per standard criteria for evidence-based status. While brief interventions for SITBs exist, future research must determine if, how, and when these interventions should be disseminated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Lifetime prevalence for many self-injurious thoughts and behaviors (SITBs) increases sharply across adolescence and remains elevated in young adulthood (Nock et al., 2008, 2013), with 19.8 to 24.0% of adolescents having experienced suicidal ideation (SI; Nock et al., 2008), 17.2% of adolescents and 13.4% of young adults having engaged in non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI; Swannell et al., 2014), and 3.1 to 8.8% of adolescents having made a suicide attempt (Nock et al., 2008). By the time they enter college, 35.8% of students seeking out mental health treatment report “seriously considering” attempting suicide at some point in their lives (Center for Collegiate Mental Health, 2018). SITBs, particularly non-suicidal self-injury, predict future suicidal behaviors (Asarnow et al., 2011; Cox et al., 2012; Ribeiro et al., 2016a; Whitlock et al., 2013), indicating a serious need for their early detection, prevention, and treatment. Given an elevated SITB prevalence rate and high proportion of deaths by suicide (CDC, 2017; Nock et al., 2008), young people ages 10–24 years represent a vulnerable population in particular need of timely intervention.

Clinical psychology research identifies psychosocial interventions for SITBs in young people, including: Integrated Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Attachment-Based Family Therapy, Dialectical Behavior Therapy, and Interpersonal Psychotherapy, and others (Diamond et al., 2010; Esposito-Smythers et al., 2011; Mehlum et al., 2014; Tang et al., 2009). However, effects of interventions for SITBs are small and inconsistent (Brausch & Girresch, 2012; Glenn et al., 2015; Gonzales & Bergstrom, 2013; Nock, 2010). In fact, meta-analytic evidence suggests significant reductions in average treatment effect size over the past five decades (weighted mean risk ratios = 0.68–0.91 in 1980s to 2010s), and effect sizes appear consistently small across age, intervention type, and SITB outcome (Fox et al., 2020). More recently, another meta-analysis corroborated this pattern of results in youth; authors found largely non-significant mental health treatment effects for SITBs in children and adolescents (Harris et al., 2022). Together, these statistics reflect the low potency of existing interventions despite > 50 years of research on SITB prevention and treatment.

In addition to this lack of potency, existing treatments for SITBs have limited accessibility. More than 67% of adolescents who report past-year suicidal ideation, and more than 50% who endorse a past-year suicide plan or attempt, also report having zero contact with a mental health specialist in the previous 12 months (Husky et al., 2012). Even among those who initially seek help, uptake is low, and attrition is high (Granboulan et al., 2001; Lizardi & Stanley, 2010; Piacentini et al., 1995; Trautman et al., 1993). After a recent suicide attempt, one sample of adolescents attended a median of 4 outpatient sessions following an emergency room referral (Piacentini et al., 1995). In a second sample of adolescents who recently attempted suicide, over 25% attended zero scheduled outpatient sessions after leaving the emergency room, ~ 11% attended only one session, and less than one-third of adolescents attended all of their scheduled sessions (Granboulan et al., 2001). Low uptake and high attrition indicate the current structure of SITB interventions does not consistently reach young people who are in great need of care.

Further, in many real-world contexts, the window of opportunity for SITB intervention is often very limited. One analysis of > 115,000 hospital encounters for suicide attempts and ideation among US youth found that more than half of the encounters involved a stay of 0–1 days; nearly 85% of encounters ended in discharge within 6 days (Plemmons et al., 2018). Patients are also at particularly high risk for suicide attempts and suicide deaths in the months after a hospital discharge (Brent et al., 1993; Chung et al., 2017; Goldston et al., 1999; Prinstein et al., 2008). A review of 48 studies found that over a quarter of suicide-related events (i.e., attempts, deaths) occurred within the first month post discharge from hospital—and 40% occurred within three months (Forte et al., 2019). In these cases, full-length intervention may not be completed prior to discharge or SITB recurrence; brief interventions designed to quickly and effectively intervene during windows of elevated risk have potential for high impact.

Creating brief, well-targeted interventions for SITBs may increase the likelihood of young people receiving a full, intended intervention dosage—potentially boosting intervention efficacy. Several brief intervention trials to date have observed low attrition rates; in a small RCT, a 4-session parent training program had > 90% session attendance (Pineda & Dadds, 2013), and single-session, emergency room-based interventions have reported 100% intervention completion across multiple trials (Glenn et al., 2015). If individuals typically receive a handful of their planned sessions, interventions designed to be brief would encourage intentional decision-making around the therapeutic content most patients actually receive. Additionally, patients could feasibly complete these briefer interventions during short, clinically important periods where risk is elevated.

Evidence suggests it is worth taking a closer look at briefer mental healthcare options for SITBs in young people. For one, there is a clear demand, as calls for briefer SITB interventions are widespread in the suicide literature (Glenn et al., 2015, 2019; Lizardi & Stanley, 2010; McCabe et al., 2018; Stanley & Brown, 2012; Stewart et al., 2019). Further, brief interventions have shown promise for treating psychiatric problems in youth. “Single-session interventions,” very brief treatments designed to last one session, have comparable meta-analytic effect sizes to traditional-length psychotherapies for other forms of youth psychopathology (meta-analytic g’s = 0.32 versus 0.46 overall; Schleider & Weisz, 2017; Weisz et al., 2017). Additionally, two meta-analyses including a combined > 340 SITB treatments suggest that treatment length is weakly and inconsistently related to treatment effect size—particularly in youth (Fox et al., 2020; Harris et al., 2022). Given that many young people are unable to access any treatment, and treatment dropout rates are quite high, null to weak impacts of treatment length on efficacy suggest a distinct need to explore brief treatment options.

Still, with many existing interventions designed to last upwards of 6 months (Brent et al., 2009; Esposito-Smythers et al., 2011; Rossouw & Fonagy, 2012; Taylor et al., 2011) and others requiring multiple therapists or treatment-related components every week (Bettis et al., 2020; Glenn et al., 2019), knowing how to treat SITBs in settings with real-world time constraints presents a real challenge. Average SITB intervention length in randomized trials far exceeds the time that many can dedicate to treatment (intervention Ms = 12.76 and 23.83 weeks for youth and all age groups, respectively; Harris et al., 2022; Fox et al., 2020). SITBs are complicated, multidetermined phenomena (Fox et al., 2019; Franklin et al., 2017; Ribeiro et al., 2016b), and people often struggle with multiple comorbidities (Kavalidoua et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020); it is easy to understand why treatment developers often design complex, lengthy, and resource-intensive treatments. However, without simultaneous efforts to evaluate brief SITB interventions and organize their evidence base, much of the resulting literature does little to help providers or policy-makers with limited time and resources.

While preliminary attempts to identify brief, effective interventions for SITBs exist, they remain incomplete. Several reviews focus only on treatment effects for certain outcomes (e.g., suicidal ideation, suicidal behavior)—failing to include intervention effects on other important SITBs, like non-suicidal self-injury (Doupnik et al., 2020; du Roscoät & Beck, 2013; Inagaki et al., 2019; McCabe et al., 2018). Earlier reviews also focus soley on interventions designed to target SITBs, thereby excluding treatments designed to target other, related outcomes (e.g., depression) that may have secondary treatment effects on SITBs (McCabe et al., 2018). Additionally, several of these reviews only include trials that recruited participants from emergency department or other healthcare settings (Inagaki et al., 2019; McCabe et al., 2018; Milner et al., 2015), potentially missing brief interventions delivered in community and school-based settings. Many reviews further limit their search by intervention modality (e.g., excluding self-guided interventions, interventions not delivered in-person, or psychotherapy; Doupnik et al., 2020; du Roscoät & Beck, 2013; McCabe et al., 2018). Finally, none of the above reviews focus entirely on brief SITB interventions for young people, despite the elevated risk for SITBs within this age group (Nock et al., 2008). Therefore, identifying brief interventions for SITBs in young people—across outcomes, treatment targets, settings, and modalities—remains important, yet underexplored.

The present study aims to identify and evaluate brief psychosocial interventions for SITBs in young people. After conducting a literature search, we describe each brief intervention and evaluate efficacy, as indexed by performance in intervention versus control groups. This review will help determine/identify: (1) what brief interventions for SITBs exist, (2) if these brief options can reduce SITBs, (3) the quality of evidence for brief interventions to date, and (4) gaps in the existing knowledge surrounding brief interventions for SITBs in young people.

Method

Literature Search

Given the present study represents a systematic review paper of previously published work, ethics approval was not required. All search and analytic methods were preregistered via PROSPERO (record ID: CRD42020171948).Footnote 1 We conducted searches across electronic databases (PsychINFO, MEDLINE, ERIC, Open Dissertations), and manually searched other relevant manuscripts (Doupnik et al., 2020; du Roscoät & Beck, 2013; Fox et al., 2020; Glenn et al., 2015, 2019; Inagaki, et al., 2019; McCabe et al., 2018; Melhem & Brent, 2020; Milner et al., 2015; Schleider et al., 2020) for randomized controlled trials and quasi-experimental studies conducted in the past 50 years that evaluate effects of brief interventions on self-injurious thoughts and behaviors in young people (January 1, 1970–January 31, 2020). Search terms included: child, teen*, adolescen*, youth*, pediatric, college student, college students, young adult, or young adults; and suicid*, self-injury, self-harm, self-mutilation, self-cutting, cutting, self-burning, self-poisoning, NSSI, or SITB; and intervention, prevention, treatment, program, randomized, RCT, workshop, field trial, or training.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Articles available in English; (2) Mean age between 10.0 and 24.0 years, per the World Health Organization’s definition of “young people”; (3) Participants received one or more non-pharmacological intervention condition(s) or a comparison condition (e.g., treatment as usual) with a randomized-controlled or quasi-experimental trial design. To be included, a study’s comparison condition must represent a group of individuals that is distinct from the intervention group; (4) The trial included at least one treatment outcome evaluating young people’s self-injurious thoughts or behaviors. To be included, the outcome must be measured post treatment in the treatment and comparison conditions; (5) The trial was conducted within the past 50 years (1970–2020); (6) At least one active intervention in the trial is “brief,” as defined in a prior review of brief, youth-directed interventions (see definition below). All articles meeting the above criteria were included, regardless of recruitment method, intervention setting, intervention delivery modality, and whether or not each intervention specifically targeted SITBs.

Consistent with a recent review of brief interventions for youth psychopathology (Schleider et al., 2020), we defined “brief interventions” as interventions not exceeding 240 min, or four 60-min sessions in total length. Youth complete an average of ~ 3.9 treatment sessions in real-world clinical settings (Harpaz-Rotem et al., 2004), ~ 25% of adolescents seeking outpatient psychotherapy end treatment after 1–2 sessions (Abel et al., 2020), and attendance is low even among adolescents with post-emergency room referrals following a suicide attempt (average and median sessions attended = 5.9 and 4, respectively; Granboulan et al., 2001; Lizardi & Stanley, 2010; Piacentini et al., 1995). Therefore, identifying evidence-based, brief treatments for SITBs may help direct young people, parents, and providers toward tools with the greatest potential for impact, given the reality of limited treatment time.

Notably, many interventions for SITBs in youth include some form of follow-up contact after an initial clinical encounter (e.g., via phone, email, or postcards). Thus, this review used a systematized approach to ‘counting’ such follow-ups either part of, or adjunctive to, a given brief intervention. Specifically, follow-up contacts were not counted toward intervention length unless these follow-up contacts (1) were a structured, standardized part of the intervention (i.e., study investigators intended for all participants to be contacted in a uniform manner), and (2) included content designed to be therapeutic (i.e., above and beyond clinical or resource referrals).

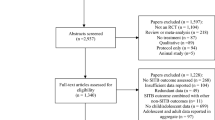

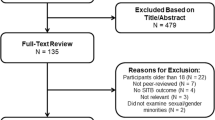

To begin the review process, article screening was conducted by the first author and a trained research coordinator (second author). These two individuals independently determined whether articles met inclusion criteria 1, 3, and 5 (written in English; one or more non-pharmacological treatment(s) tested via RCT or quasi-experimental design; released within the specified date range), based on each abstract. After initial abstract screening, these two raters independently determined whether remaining articles met inclusion criteria 2, 4, and 6 (mean age between 10.0 and 24.0 years; at least one post-treatment SITB outcome for both conditions; “brief interventions” fewer than four 60-min sessions or ≤ 240 min of total length) based on the full texts. Any disagreements were resolved via discussion at both rounds of initial review. Studies meeting all above inclusion criteria after these two stages of screening were included in the present review (see Fig. 1).

Data Extraction, Coding, and Processing

Once final studies were identified, each article was coded at the full-text level for specific study and sample characteristics: study year, publication status (peer-reviewed versus unpublished), participant demographics (mean age, sex, gender identity, LGBTQ+ identity, racial and/or ethnic identity), and sample type (recruitment within clinical versus community settings).

Additional coded study-level information included treatment length (total minutes, number of sessions, and number of weeks), study follow-up length (weeks), intervention delivery format (self-administered or administered by mental health provider, other health provider, or school staff), delivery setting (outpatient mental healthcare setting, hospital, school, research lab, community center, or remotely by technology), and training required for those administering the intervention (hours; for non-self-administered studies only). For studies where “treatment as usual” was compared to one or more brief interventions plus treatment as usual, coders did not consider treatment as usual components when estimating brief intervention duration. Wherever possible, estimated intervention duration in minutes was based on author-reported estimates for intended intervention length, followed by the reported mean duration, the median duration, and the maximum duration of intervention. If a manuscript did not report intervention duration (minutes), coders contacted the corresponding author of the paper to determine an author-based estimate. Where author-based estimates were unavailable, coders estimated duration in minutes based on standardized values (i.e., phone calls = 15 min; postcards, notes, emails = 5 min; texts, posters = 1 min of intervention).

Coders recorded all intended intervention targets—per each manuscript’s description of intervention—to evaluate whether each intervention was specifically designed to target SITBs, or whether it was designed to treat a different mental health outcome. For example, intervention targets could have included: SITBs, depression, substance use, personality dysfunction, and/or other mental health problems. Additionally, coders recorded whether each trial was registered on a clinical trials registry (e.g., clinicaltrials.gov; yes or no), and, if so, which primary outcome was specified in the registration. Using this information, coders indicated whether the primary outcome reported on the registration (if any) matched the primary outcome reported in each trial. To capture attrition, coders extracted the number of participants assigned to the treatment(s) versus control condition, number of participants who started the treatment(s) (percent of participants in the treatment condition who attended at least one session/initiated self-administered treatment), and participant retention in treatment versus control condition (percent by condition at final follow-up). As some interventions may target SITBs in young people via training others (e.g., parents or health provider trainings), coders extracted data for the person receiving intervention content (young person, parent, health professional, or school staff).

Specific codes also provide information about comparison conditions. Coders labeled whether each comparison condition was labeled “waitlist control/no treatment,” “treatment as usual/usual care” (TAU/UC), “psychoeducation,” or “active comparator.” Considering the wide variation of comparison conditions utilized in youth mental health treatment research (Weisz et al., 2013), coders recorded how “TAU/UC,” “psychoeducation,” or “active comparator” was defined for each study condition (per authors’ written descriptions). Coders noted instances where the description of a comparison condition was unclear or incomplete.

Lastly, coders extracted specific information about the SITB outcome(s) in each study: the total number of SITB-related outcomes measured, whether each study observed any positive, statistically significant effects across all SITB outcomes (yes or no), and, if so, which specific outcome(s) improved relative to the control group. Additionally, coders calculated what percentage of each study’s outcomes were significantly improved for SITB-specific (e.g., non-suicidal self-injury) and non-specific outcomes (e.g., depression). For studies evaluating outcomes across multiple manuscripts (i.e., multiple papers using the same sample), coders counted outcomes from all earlier papers in addition to outcomes assessed in the included study.

Coders also extracted the following for each SITB outcome measured: the specific SITB outcome measure(s) used (e.g., Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire), the form of SITB outcome measurement (self-report, interview, or mixed), and the type of SITB outcome. To facilitate comparisons with earlier meta-analyses evaluating mental health treatment effects on SITBs (Fox et al., 2020), SITB types included: non-suicidal self-injury, suicide ideation (including suicidal intent and plans), suicide attempts, suicide deaths, suicide attempts and deaths (if combined in outcome), self-harm (all self-harm, regardless of intent), lumped suicidal thoughts and behaviors (if combined in outcome), lumped self-injurious thoughts and behaviors (if combined in outcome), hospitalization resulting from a SITB episode, or suicide questionnaire. Importantly, outcomes reporting a mix of SITBs and depression symptoms were not included in the present review (e.g., composite Childhood Depression Inventory scores, including the item, “I want to kill myself”). However, suicidality-specific measures that do include outcomes not directly related to SITBs were coded separately in the final “suicide questionnaire” category (e.g., Suicide Cognition Scale scores, including the item, “It is impossible to describe how badly I feel”). Coders created short descriptions of each intervention, as well as qualitatively summarized the results of each trial.

Coders evaluated the state of the evidence supporting each intervention using established rating criteria widely used within clinical psychology and psychiatry research (“well-established,” “probably efficacious,” “possibly efficacious,” “experimental,” or “questionable”; Chambless & Hollon, 1998; Chambless & Ollendick, 2001; Glenn et al., 2015; Schleider et al., 2020; Southam-Gerow & Prinstein, 2014). Intervention efficacy was assessed separately for each SITB outcome, such that each intervention could receive multiple efficacy ratings (one for each outcome assessed).

Lastly, in accordance with the Cochrane Consumers & Communication Review Group recommendations (Ryan et al., 2013), coders examined methodological variables from each study to evaluate risk of bias (e.g., masking of participants and personnel, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, etc.). For studies where participants were not assigned to a condition (i.e., quasi-experiments evaluating an intervention group vs. a retroactively identified comparison sample) this was noted explicitly, and risk of bias was not coded for selection bias, performance bias, or detection bias. Rater agreement was evaluated across all study, group, and outcome-level variables using Cohen’s kappa (average Κ = 0.84).

Results

Study Selection and Inclusion

The search identified 5138 records via database searching (n = 4203 after duplicate removal) and 18 additional records via manual search. Title/abstract screening excluded 3928 records, and 293 articles were screened at the full-text level (275 from database search, 18 from manual search). Of these 293 articles, 267 were excluded using the pre-specified inclusion criteria—yielding 26 total articles for inclusion in the present review (all published; see Fig. 1 for full details and reasons for exclusion). The first and second authors coded all 26 included articles in-full (MD and SC).

Characteristics of Included Studies

Participants

These 26 articles included 24 completely independent studies, one analysis combining additional collected data with an initial sample (Aseltine & DeMartino, 2004; Aseltine et al., 2007), and one long-term follow-up study reporting additional outcomes 14 years later (King et al., 2009, 2019)—culminating in 17,366 total young people (study Ns = 36–8389),Footnote 2 with estimates of central tendency for age (e.g., mean, median, midpoint, or estimated age based on grade-level) ranging from 14 to 19.50 years old (unweighted mean of study-level estimates = 15.85 years; see Table 1). 10.61–58.30% of the samples were reported as male; none of the included articles contained evidence that gender identity was assessed as distinct from sex, or that identity options beyond the binary (“male,” “female”) were provided. Only one study reported the number or proportion of LGBTQ+ participants (Asarnow et al., 2017). A majority of articles (15 of 26) reported research conducted in majority-white samples (range of study-level estimates = 33.15–86.11% white). While data for participants’ racial and ethnic identities were often unreported, the proportion of white participants was reported far more frequently (reported in 18 of 26 articles) than the proportion of participating Black, Hispanic, Asian, Pacific Islander, or Native young people (reported in 15, 15, 9, 3, and 7 of 26 articles, respectively). Overall, young people included in these studies were recruited from community (i.e., non-selected; n = 8), clinically selected (n = 4), outpatient (n = 1), and inpatient/hospital/residential samples (n = 14); notably, the total n does not equal 26, as multiple studies recruited participants from more than one of the above sample types, and one study was a long-term follow-up study within the same, original sample (King et al., 2019). One study specifically recruited participants from a group of treatment-seeking individuals who were ineligible to receive specialty mental health services (Robinson et al., 2012).

Study Design & Risk of Bias

A majority of included articles (20 of 26 articles) reported results from randomized trials (see Table 2 for study designs and risk of bias); however, multiple non-randomized trials (n = 2) used an alternating allocation sequence, and several articles (n = 4) used a quasi-experimental design to make retrospective comparisons with a distinct, matched and non-randomized comparison group (e.g., comparing intervention group participants to individuals who previously visited the hospital prior to intervention rollout; comparing intervention group to a matched control school). Comparison groups fell into four broad categories, sorted based on authors’ description: wait list/no treatment (n = 6), treatment as usual (n = 14), psychoeducation (n = 3), and active comparison (n = 3).

Risk of bias codes (Ryan et al., 2013) suggested varying levels of possible bias across studies. Three of 26 articles met criteria for “high” risk of selection bias (i.e., non-random assignment or study staff aware of allocation sequence). A majority (n = 14) met criteria for “high” risk of performance bias—indicating either participants or study personnel were unmasked to study condition. Seven articles did not provide clear information about randomization method, allocation concealment, or masking of participants and study staff. By comparison, risk of detection bias was low across all 26 articles; four articles met criteria for “high” risk (i.e., unmasked outcome assessors), and three articles did not clearly report whether outcome assessors were masked. Four articles reported using quasi-experimental designs without allocating participants to specific groups; these articles were not coded for selection, performance, or detection bias. Probability of attrition bias was indexed as a function of difference in attrition between groups relative to overall attrition (What Works Clearinghouse, 2020), with higher study attrition and differential attrition reflecting higher probability of bias. Eight articles met criteria for “high” risk of attrition bias, and 10 articles either lacked sufficient information to determine risk of attrition bias or the risk of attrition bias was unclear.

Fewer than half (n = 12) of the 26 articles were pre-registered on clinicaltrials.gov or another clinical trials registry included on the World Health Organization’s International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP; World Health Organization, 2022; see Table 3 for details about study pre-registrations and follow-ups). Of these 12 pre-registered studies, only seven studies contained 1:1 match between pre-registered primary outcome(s) and primary outcome(s) reported in the published manuscript. Two of these 12 studies had previously published the pre-registered primary outcome in an earlier paper, and three studies met criteria for a partial match between pre-registered and reported primary outcomes (i.e., multiple outcomes were pre-registered as primary, and only some of the published primary outcomes match the pre-registered outcomes). Because a majority of studies were not pre-registered (n = 14), risk of reporting bias (i.e., selective outcome reporting) was difficult to discern; one was pre-registered without specific outcomes listed, and four articles pre-registered outcomes that were not reported in the published manuscript.

Interventions

Twenty-three distinct and “brief” interventions were evaluated across all 26 articles. Overall, these interventions were designed to target a variety of outcomes—with some primary treatment targets classified as SITBs (e.g., suicide attempts, suicidal ideation, non-suicidal self-injury), and others not classified as SITBs (e.g., attitudes about suicide, problem solving skills, motivation for follow-up treatment). Many of these 23 interventions were disseminated using more than one of the following settings/contexts (see Table 4 for full details about intervention characteristics): outpatient mental health clinics (n = 2), inpatient clinics (n = 4), emergency rooms/departments (n = 5), school/after-school (n = 5), research laboratories (n = 1), home-based in-person (n = 1), self-guided digital (n = 3), and teletherapy (n = 7). Additionally, three interventions were delivered within a broader hospital setting (n = 1), via mailed postcards (n = 1), and a psychiatry department and health center (n = 1). Most of the 23 interventions were at least partially youth-directed (n = 20); however, several studies directed intervention content toward school staff (n = 2), youth-nominated adults (n = 1), family (n = 3), or parents/caregivers (n = 4)—either in addition to, or in lieu of, working directly with youth (e.g., “gatekeeper” trainings). Finally, most interventions (16 of 23) were delivered by one, or multiple, of the following types of trained health provider(s): psychiatrists (n = 1), doctoral-level psychologists (n = 5), Masters-level clinicians (including social workers; n = 5), trainee clinicians (e.g., graduate students; n = 2), nurses (n = 2), or broader provider titles (e.g., “hospital staff,” “clinicians,” “therapists,” “doctors”; n = 7). One intervention involved a gatekeeper training of school staff using “certified intervention trainers,” and two interventions were administered by school staff. Only four of 23 interventions required no provider (i.e., completely self-administered interventions). Of studies that used trained providers, a vast majority did not specify the number of required training hours (reported in five of 22 articles; range < 1–40 h).

While all interventions included in this review were brief, the duration of intervention varied dramatically across multiple indices: minutes (range 15–240 min), number of “sessions”/modules/discrete contacts (range 1–126; in some cases, interventions included daily text messages over a number of weeks), as well as number of days (range 1–336 days) and weeks (range < 1–48) elapsed from start to finish of all standardized intervention components. Details about intervention access within an intent-to-treat sample (i.e., among those who had been allocated to a study condition) were often unknown—including percent of participants who started and completed each intervention, as well as the average number of minutes of intervention completed.

Despite heterogeneity in treatment duration and details about delivery, many of the 23 evaluated interventions included similar content; a majority incorporated elements of problem-solving therapy, motivational interviewing to boost motivation for change and/or treatment uptake, techniques based on cognitive-behavioral therapy, safety planning, or facilitation/referral of outpatient care. Other interventions focused primarily on risk assessment and psychoeducation about suicide (see Table 4 for full overview).

Outcomes

Most articles reported multiple SITB outcomes (mean: 2.58; range 1–8) and non-SITB outcomes (mean: 6.77, range 0–26). Specifically, studies evaluated intervention effects on the following categories of SITB outcomes (see Table 5): non-suicidal self-injury (n = 2), suicidal ideation (n = 15), suicide attempts (n = 17), suicide deaths (n = 2), self-harm (i.e., regardless of intent to die; n = 1), lumped suicidal thoughts and behaviors (n = 2), lumped self-injurious thoughts and behaviors (n = 3), hospitalization resulting from a SITB episode (n = 3), and suicide questionnaire with items not relating to SITBs (e.g., Suicide Cognition Scale, with item “it is impossible to describe how badly I feel”; n = 1). Six studies evaluated other SITB outcomes, including emergency department visits for SITB episodes, self-reported chance of considering or attempting suicide in lifetime, self-harm episodes not leading to an emergency department visit, etc. These outcomes were measured across a wide range of follow-up periods (range: 0 days–14 years).

Did Brief Interventions Significantly Improve SITBs?

Trial results across all 26 articles were mixed; nine of 26 (34.62%) reported any significant positive effect of intervention on at least one SITB outcome. A 10th article and long-term follow-up study of one of the above nine positive trials (King et al., 2009) found no significant difference between groups on any SITB-specific outcome 14 years later (King et al., 2019). For two of 26 articles (7.69%), raw data were presented for all measured SITB outcomes in both the intervention and comparison groups in lieu of between-groups significance tests. Eleven of 26 (43.31%) reported null effects across all SITB outcomes, and three of 26 (7.69%) reported at least one negative SITB effect in the brief intervention group relative to a comparison group (noted in Tables 3, 5). Notably, in two of these three instances of negative SITB outcomes, brief intervention groups were compared to a second, longer-duration intervention group; one study found that a brief single-call intervention (~ 40 min) was outperformed by a multiple-call intervention (~ 240 min) that also met this review’s criteria for brief intervention (Rengasamy & Sparks, 2019), and the other study found that a brief enhanced treatment as usual intervention (in-clinic session + three follow-up calls, ~ 95 min) was outperformed by a 12-week cognitive behavioral therapy family intervention (12 weekly sessions, ~ 1080 min; Asarnow et al., 2017). Full descriptions and results for each intervention are summarized in Tables 4 and 5.

Of the nine studies that reported a positive intervention effect on at least one SITB outcome, most (n = 7; 77.78%) were randomized trials. Five of the nine positive trials compared the brief intervention group to a waiting list/no treatment control, three to a treatment as usual group, one to a psychoeducation control. Among these nine trials with at least one positive SITB effect, the percentage of SITB outcomes improved (out of the total number of SITB outcomes measured) ranged from 50 to 100% at the first follow-up time point, and 0–50% at the last follow-up time point. Average follow-up length for the nine positive trials was 16.00 and 23.20 weeks for first and last follow-ups, respectively. Only two of the nine positive trials measured at least one SITB outcome at first and last follow-up time points (Fitzpatrick et al., 2005; King et al., 2009). Of these two trials with at least one SITB outcome measured at first and last follow-ups, neither reported sustained effects on the same SITB outcome across both time points; one trial found significant reductions in suicidal ideation at 6-week follow-up that were not sustained at 12-month follow-up (King et al., 2009), and one trial reported significant reductions in lumped self-injurious thoughts and behaviors using latent growth curve analyses across all follow-up time points (i.e., no reporting of between-group effects specific to first and last follow-up time points; Fitzpatrick et al., 2005).

A variety of intervention durations (range 35–240 min) were associated with at least one significant SITB effect. The majority of the nine positive trials (n = 5) delivered interventions via mental health professionals—with a remaining one delivered by mental health school staff (i.e., counselors), two delivered by other school staff, and one self-administered. For intended treatment audience, three studies intervened directly with youth, two involved youth and family or parents/caregivers, three involved youth and school staff, and one was directed at youth-nominated adults. Finally, four of the nine positive trials used community samples, two used screened (i.e., clinically selected) samples, and three used inpatient/hospital/residential samples. One recruited participants from screened, outpatient, and inpatient/hospital/residential settings.

Taken together, the nine studies that reported a positive treatment effect on at least one SITB outcome varied in their design, percentage of SITB outcomes improved, type of comparison group, intervention duration, intended intervention audience, and type of sample recruitment. Most studies with at least one positive SITB effect delivered interventions via mental health professionals—with several delivered by school staff. No positive trial compared a brief intervention to an active comparator, and only one study involved completely self-administered intervention.

Which Brief Interventions Significantly Improved SITBs?

Six of the 23 included interventions were associated with significant SITB improvement in at least one study. Notably, all six of these interventions were specifically designed to target reductions in at least one SITB. In other words, none of the interventions designed to primarily target other, non-SITB outcomes (e.g., depression) showed evidence of positive treatment effects for SITBs. One of these 6 interventions met evidence-based status criteria for “probably efficacious” (Chambless & Hollon, 1998; Chambless & Ollendick, 2001; Glenn et al., 2015; Schleider et al., 2020; Southam-Gerow & Prinstein, 2014), four for “possibly efficacious,” and one for “experimental.” Two of these six interventions were associated with at least some publicly available intervention materials (e.g., training manuals, treatment manuals, or other open-access materials); in cases where no intervention materials were made public (four of six), descriptions of each intervention’s content are based on text published within each article (see Tables 4 and 5 for an overview of intervention details and results).

Two of these six interventions had multiple included studies find positive results on at least one SITB outcome: (1) Signs of Suicide (SOS; Aseltine et al., 2007; Aseltine & DeMartino, 2004; Schilling et al., 2016), a 120-min psychoeducational curriculum delivered by trained school staff, and (2) Family-Based Crisis Intervention (FBCI; Wharff et al., 2012, 2019), a 90-min family crisis intervention delivered within the emergency department (FBCI). Specifically, SOS was designed by a non-profit organization (Screening for Mental Health, Incorporated) to teach high school students how to recognize and respond to signs of suicide in themselves and from their peers (e.g., symptoms of depression, alcohol use). Using a short video and discussion guide, students are encouraged to take the potential signs of suicide seriously, to acknowledge them using empathy, and to tell a trusted adult whenever they are identified. The SOS program is available for purchase online (MindWise Innovations, 2022) with some materials publicly available for parents online (MindWise Innovations, 2018). Across two randomized trials (Aseltine & DeMartino, 2004; Schilling et al., 2016) and one re-analysis including a second wave of data collection (Aseltine et al., 2007), SOS students were less likely to report suicide attempts three months later, relative to students who received no treatment—thus meeting evidence-based status criteria for “level 2: probably efficacious.” Additionally, the FBCI intervention was developed by study authors to build rapport between adolescents and their families—simultaneously building cognitive behavioral (e.g., relaxation, problem-solving, cognitive reframing) and safety planning skills via non-judgmental collaboration. FBCI was associated with fewer adolescent inpatient psychiatry admissions immediately following the intervention in one randomized trial (Wharff et al., 2019) and one quasi-experimental trial (Wharff et al., 2012)—both relative to treatment as usual. Therefore, FBCI meets evidence-based status criteria for “level 3: possibly efficacious” for inpatient psychiatric admissions.

The remaining four of these six interventions were associated with SITB improvements in a single trial. Two of these interventions focused primarily on teaching problem-solving skills: a 35-min problem-solving and coping video (Fitzpatrick et al., 2005), and six sessions of short-term problem-solving therapy delivered by trainee clinicians (PST, 225 min; Eskin et al., 2008). For both problem-solving interventions, young people were encouraged to identify key problems and their associated thoughts, emotions, and behaviors before applying learned coping skills (e.g., goal setting, distinguishing problem-solving from worry or rumination) to a personal problem of choice. Both interventions were tested in randomized trials. The 35-min problem-solving and coping video was associated with faster reductions in a combined measure of suicidal thoughts and behaviors across one-month follow-up, relative to a psychoeducation control (level 3: “possibly efficacious”), and the six-session PST was associated with reduced suicide potential six weeks later in high school and university students, relative to a waiting list comparison (level 3: “possibly efficacious”).

Another two interventions—one 60-min psychoeducation intervention for youth-nominated adults (Youth-Nominated Support Team–Version II, YST-II; King et al., 2009, 2019), and one 75-min therapeutic suicide screening intervention (Teen Screen; Torcasso & Hilt, 2017)—also reported at least one positive intervention effect for SITBs in a single trial. Specifically, the YST-II intervention included one individual or group psychoeducation session directed toward youth-selected adults; during these sessions, YST intervention specialists (e.g., trained psychologists, clinicians, nurses) covered material on relevant psychiatric disorders, individualized treatment plan for each youth, common risk factors for suicide, and specific ways to access emergency services, if needed. Youth-nominated adults were also contacted by YST staff for weekly support phone calls (each ~ 15 min) to provide individual support and facilitate treatment progress for the next 12 weeks. The full YST-II intervention manual is publicly available online (King et al., 2001). In one randomized trial, YST-II was associated with decreases in suicidal ideation at six-week follow-up, relative to treatment as usual (King et al., 2009; level 3: “possibly efficacious”). However, this study detected no differences in suicidal ideation or suicide attempts at 12 months (King et al., 2009), and a 14-year follow-up study found no significant difference in suicide-related deaths between groups (King et al., 2019).

The 75-min TeenScreen intervention was developed by Columbia University as a multi-stage and therapeutic suicide screening program for high school students. To complete TeenScreen, all students finish a 10-min screening tool plus either a debriefing conversation or a clinical interview. Should a TeenScreen clinician determine a student is in need of referral for mental health services, guardians are contacted with referral information and instructions within 24 h, and the TeenScreen clinician may assist with scheduling the first appointment. Additional case management services are offered through the third session with a mental health professional if necessary. In one non-randomized, quasi-experimental comparison (level 4: “experimental”), fewer adolescents in TeenScreen schools endorsed two or more suicide attempts in the previous 12 months; notably, the study found no difference between intervention and comparison groups for the number of students endorsing a single suicide attempt at the same two-year follow-up (Torcasso & Hilt, 2017).

Which Brief Interventions Did Not Significantly Improve SITBs?

Few consistent patterns emerged between “successful” interventions and null interventions; like the six interventions with at least one observed SITB improvement, the 17 interventions with null SITB effects also varied in duration (1–240 min), audience, providers, and delivery contexts. Of these 17 null interventions, ten were completely youth-directed, six were at least partially family-directed, and one was directed at school staff. Twelve of 17 null interventions were delivered via mental health professionals (e.g., MA-level clinicians, therapists, psychiatrists, etc.), two by other adults (e.g., school staff), and three were completely self-administered. The majority of the 17 null interventions (n = 11) were delivered within healthcare settings (e.g., ER, inpatient, outpatient, etc.). Descriptively, these interventions ranged from digital CBT programs (Hill & Pettit, 2019; Whittaker et al., 2017), to psychoeducational class presentations and postcards (Robinson et al., 2012; Vieland et al., 1991; Wasserman et al., 2015), to safety planning and motivational interviewing (Czyz et al., 2019; Grupp-Phelan et al., 2019; Kennard et al., 2018; King et al., 2015; Rengasamy & Sparks, 2019), to multi-session problem-solving counseling (Perera & Kathriarachchi, 2011), to provision of hospital readmission tokens (Cotgrove et al., 1995), to in-person family session(s) plus structured follow-up phone calls (Asarnow et al., 2011, 2017; Donaldson et al., 1997; Ougrin et al., 2013). In sum, substantial heterogeneity existed across all intervention characteristics.

Discussion

Across more than 50 years of intervention research (Fox et al., 2020), clinical psychology has failed to meet the needs of young people who engage in SITBs at scale. Many young people with a recent history of SITBs never access treatment (Hom et al., 2015; Husky et al., 2012) or access only a fraction of the intended dose (Granboulan et al., 2001). Above and beyond commonly cited barriers to accessing mental health treatment (e.g., cost, time, stigma; Brown et al., 2016; Mojtabai et al., 2011), accessing treatment for SITBs may be especially challenging for young people; many fear negative consequences of disclosure (e.g., negative reactions from others, non-consensual involvement of caregivers, forced hospitalization; Fox et al., 2022; Rosenrot & Lewis, 2020). Further, many SITBs (including suicidal ideation) can rapidly intensify from one hour to the next (Kleiman et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2021)—making it difficult to access care in moments when it is needed most. Thus, there is an urgent need to identify evidence-based SITB interventions that can be deployed when time is limited. The present review, spanning 50 years of randomized and quasi-experimental intervention research, identified and summarized effects of “brief” interventions (i.e., 240 min or less) on SITBs in young people.

Across 26 identified articles, nearly two dozen brief interventions were identified and included in this review. These 23 interventions shared aspects of therapeutic content, including: problem-solving, motivational interviewing, safety planning, psychoeducation, and facilitated referral/case management. As such, many of the interventions contained at least one of two treatment components identified as possibly efficacious in a recent review of youth SITB interventions—(1) inclusion of family and (2) skills development (Bettis et al., 2020). Although the included interventions shared common therapeutic principles, they were designed for implementation across a wide range of contexts (e.g., inpatient, schools, teletherapy), durations (e.g., 35–240 min), providers (e.g., self-administered, doctoral-level psychologists, school staff), and audiences (e.g., family versus youth-directed). The existing literature therefore supports the idea that brief SITB interventions are amenable to implementation in many treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking contexts. In some cases, these interventions may be designed to make the most of limited clinical contact time—in others, to increase potential of reaching those who may not otherwise receive mental healthcare.

Despite collective evidence suggesting brief interventions can be disseminated using a variety of methods/contexts, formal evaluations of these interventions suggest mixed efficacy for addressing SITBs. Less than half of all included studies, and less than one-third of all brief interventions, found a positive intervention effect for at least one SITB outcome. More often than not, trial results were null across all measured SITB outcomes. Several articles found brief interventions performed worse than a comparison condition (in two cases, a full-length active comparator) at SITB reduction. For many existing brief interventions, the state of the evidence surrounding their ability to reduce SITBs is weak or null. Few patterns emerged between characteristics of “successful” brief interventions (i.e., those that observed at least one SITB improvement), versus those with null SITB effects.

From the 10 trials that did report a positive intervention effect on at least one SITB outcome, six brief interventions emerged as potentially helpful for improving SITBs. Each of these potentially helpful brief interventions was designed to target one or more SITB(s). Signs of Suicide (SOS) and Family-Based Crisis Intervention (FBCI) were associated with the highest degree of evidence, as multiple studies found positive effects for at least one SITB outcome (evidence-based status determined “probably efficacious” and “possibly efficacious,” respectively). These two interventions differ by content, delivery settings, providers, and audiences. The SOS intervention is a school-based, staff-delivered psychoeducational curriculum designed to teach youth to recognize (and quickly “act on”) signs of suicide (Aseltine & DeMartino, 2004; Aseltine et al., 2007; Schilling et al., 2016); by contrast, FBCI is a clinician-delivered crisis intervention based on cognitive-behavioral and family systems treatment models, delivered to youths and families in the emergency department (Wharff et al., 2012, 2019). Notably, for both interventions with significant SITB findings across multiple trials (SOS and FBCI), members of the same research team conducted the original trial and follow-up research.

The remaining four of the six brief interventions with any significant reduction in SITBs were supported in a single included trial. These four interventions included: two problem-solving interventions (both “possibly efficacious”; Eskin et al., 2008; Fitzpatrick et al., 2005), a therapeutic screener and briefing interview (“experimental”; Torcasso & Hilt, 2017), and a psychoeducational, social network intervention informed by theories of social support and health behavior (“possibly efficacious”; King et al., 2009). Notably, two of these interventions were also associated with null effects for closely related SITB outcomes (King et al., 2009, 2019; Torcasso & Hilt, 2017). Further, an earlier randomized trial testing a previous version of one of these interventions (YST Version I; > 240 min, not included in this review) failed to significantly reduce suicidal ideation or attempts 6 months later, relative to the control (King et al., 2006). Thus, while some evidence suggests these interventions may help reduce SITBs, replication is needed to determine the consistency and longevity of these effects.

Future Directions for Brief SITB Intervention Research

The current review demonstrates that many brief interventions for SITBs already exist and have been implemented into many education, health, and mental health contexts. However, several limitations and gaps within the existing literature are worth addressing in future research. Firstly, better transparency and consistency in reporting standards across all intervention trials (both randomized and quasi-experimental) would make it easier to evaluate the strength of results. More than half of the included articles did not pre-register their research objectives, design, or outcomes on a public trial registry—making it difficult to identify possible reporting bias or to distinguish between a priori and post hoc tests. Transparency about primary versus secondary outcomes is especially important, given the large number of SITB (mean: 2.58) and non-SITB outcomes (mean: 6.77) that were evaluated within each trial, as well as the many ways to measure a given SITB (e.g., any engagement, frequency of engagement, time until engagement). A majority of studies also met criteria for “high” risk of performance bias, indicating either study staff or participants were aware of condition assignment. Rigorous and transparent research helps avoid continued dissemination of unhelpful or actively iatrogenic interventions (Simon et al., 2022). Small, yet important adjustments to study design and initiation (e.g., pre-registering trial outcomes, ensuring proper masking) would maximize our ability to learn from null trial results and prevent possible harm.

Secondly, existing brief intervention research targets SITB outcomes related to suicide (e.g., suicidal ideation, suicide attempts) far more often than others (non-suicidal self-injury). The present review includes only two brief intervention trials that measured NSSI at follow-up—neither of which yielded intervention-related improvements (Asarnow et al., 2017; Kennard et al., 2018). Given that > 17% of adolescents report some experience with NSSI (Swannell et al., 2014), future intervention research may wish to prioritize brief, accessible intervention options for young people engaging in self-injurious behavior without an intent to die.

Future efforts should also prioritize further improving treatment accessibility. While all included interventions were “brief,” 15 of the 26 included articles focused on youth who were already receiving mental health services (i.e., outpatient or inpatient settings). Continuing to expand delivery of brief interventions beyond traditional healthcare settings (e.g., emergency rooms; inpatient clinics and outpatient clinics) may improve access for the many youth who never access formal or specialized mental health treatment (Hom et al., 2015; Husky et al., 2012). Further, one-third of the included interventions were associated with at least some publicly available material (e.g., open-access treatment materials or manuals). Providing free and easily-accessible treatment content may promote fidelity to the original intervention and create greater opportunities for broad dissemination.

Collecting additional information may also help us better understand if, how, and when brief SITB interventions should be implemented. Several of the included studies did not specify a singular therapy type on which the intervention was based (e.g., Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Dialectical Behavior Therapy, Problem-Solving, etc.), and many interventions contained components from multiple therapies—making it difficult to sort interventions into distinct theoretical categories. A small minority of the included studies included information about the number of individuals who started and completed each intervention among an intent-to-treat sample (i.e., of those who were randomized/enrolled). Further, a vast majority of trials did not report the number of hours necessary to train the providers delivering each intervention. These data are essential to evaluating scalability and sustainability of intervention strategies across various settings.

Additionally, many articles lacked detailed demographic information across multiple participant identities (race/ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation). Studies were far more likely to measure and report information about the number of participating white youth than Asian, Pacific Islander, and Native or Indigenous youth. Only one of 26 articles included information about lesbian, gay, or bisexual youth, and none of the included articles appeared to measure gender identity beyond sex. This lack of demographic information is alarming, given LGBTQ+ youth are more likely to experience SITBs relative to cisgender heterosexual peers (Rogers & Taliaferro, 2020), and Asian, Pacific Islander, and Native American youth with past-year suicidal ideation are less likely to access mental health services for their ideation, relative to non-Hispanic white youth with a similar SITB history (Nestor et al., 2016). Omitting questions or data related to youth identities prevents evaluation of whether interventions differ in effectiveness, acceptability, or accessibility across diverse sets of identities and their intersections (Pachankis, 2018). Thus, consistently collecting demographic information is one important part of evaluating whether any mental health intervention is increasing equitable access to quality mental healthcare.

Finally, continued evaluation of novel and existing brief SITB interventions is necessary. Large-scale randomized trials of the six interventions identified as “experimental,” “possibly efficacious,” or “probably efficacious”—conducted by independent research teams—will provide greater insight into efficacy. Large studies are also required for well-powered, close examination of which individuals may benefit most from each intervention. Future evaluations may also prioritize direct comparisons of brief intervention content (e.g., head-to-head trials evaluating brief problem-solving vs. brief family systems approaches); these results would help guide which “active ingredients” to prioritize when designing and implementing future brief interventions. Continued development of novel brief interventions is also necessary to meet demands within changing contexts (e.g., isolation and shut downs related to COVID-19). Given that brief SITB interventions will (by necessity) continue to exist, these interventions require consistent, collective investment.

Conclusions

Full-length treatments are crucial for addressing SITBs, and they cannot adequately address the needs of all young people in need of support, at all times when support is needed. Brief interventions for SITBs provide one possible avenue toward improving access to evidence-based mental healthcare; however, mixed results and limited supporting evidence make it difficult to discern if, how, and where brief SITB interventions should be implemented. Future research must address real-world gaps in access to adequate SITB treatment.

Data Availability

The author confirms that all data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Notes

To include non-randomized trials, to facilitate comparisons with prior work (Fox et al., 2020), and to account for substantial anticipated heterogeneity in SITB measurement between trials, we preregistered the present study as a systematic review over a meta-analysis.

Estimated total N is approximate, given that the exact sample size for between-group comparisons (i.e., size of intervention and comparison school samples) in Torcasso and Hilt (2017) is unknown.

References

Abel, M. R., Bianco, A., Gilbert, R., & Schleider, J. L. (2020). When is Psychotherapy Brief? Considering sociodemographic factors, problem complexity, and problem type in U.S. adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2020.1759076

Asarnow, J. R., Hughes, J. L., Babeva, K. N., & Sugar, C. A. (2017). Cognitive-behavioral family treatment for suicide attempt prevention: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(6), 506–514.

Asarnow, J. R., Porta, G., Spirito, A., Emslie, G., Clarke, G., Wagner, K. D., Vitiello, B., Keller, M., Birmaher, B., McCracken, J., Mayes, T., Berk, M., & Brent, D. A. (2011). Suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in the treatment of resistant depression in adolescents: Findings from the TORDIA study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 50(8), 772–781.

Aseltine, R. H., Jr., & DeMartino, R. (2004). An outcome evaluation of the SOS suicide prevention program. American Journal of Public Health. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.94.3.446

Aseltine, R. H., James, A., Schilling, E. A., & Glanovsky, J. (2007). Evaluating the SOSsuicide prevention program: A replication and extension. BMC Public Health, 7(1), 1–7.

Bettis, A. H., Liu, R. T., Walsh, B. W., & Klonsky, E. D. (2020). Treatments for self-injurious thoughts and behaviors in youth: Progress and challenges. Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 5(3), 354–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/23794925.2020.1806759

Brausch, A. M., & Girresch, S. K. (2012). A review of empirical treatment studies for adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 26(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1891/0889-8391.26.1.3

Brent, D. A., Greenhill, L. L., Compton, S., Emslie, G., Wells, K., Walkup, J. T., Vitiello, B., Bukstein, O., Stanley, B., Posner, K., Kennard, B. D., Cwik, M. F., Wagner, A., Coffey, B., March, J. S., Riddle, M., Goldstein, T., Curry, J., Barnett, S., et al. (2009). The Treatment of Adolescent Suicide Attempters Study (TASA): Predictors of suicidal events in an open treatment trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(10), 987–996. https://doi.org/10.1097/chi.0b013e3181b5dbe4

Brent, D. A., Kolko, D. J., Wartella, M. E., Boylan, M. B., Moritz, G., Baugher, M., & Zelenak, J. P. (1993). Adolescent psychiatric inpatients’ risk of suicide attempt at 6-month follow-up. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 32(1), 95–105.

Brown, A., Rice, S. M., Rickwood, D. J., & Parker, A. G. (2016). Systematic review of barriers and facilitators to accessing and engaging with mental health care among at-risk young people. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry: Official Journal of the Pacific Rim College of Psychiatrists, 8(1), 3–22.

Center for Collegiate Mental Health (2018). 2018 Annual Report. [Data file]. Retrieved from: https://sites.psu.edu/ccmh/files/2019/09/2018-Annual-Report-9.27.19-FINAL.pdf.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; 2017). Web-based injury statistics query and reporting system [Data file]. Retrieved from: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/suicide.shtml#part_154968.

Chambless, D. L., & Hollon, S. D. (1998). Defining empirically supported therapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66(1), 7–18.

Chambless, D. L., & Ollendick, T. H. (2001). Empirically supported psychological interventions: Controversies and evidence. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 685–716.

Chung, D. T., Ryan, C. J., Hadzi-Pavlovic, D., Singh, S. P., Stanton, C., & Large, M. M. (2017). Suicide rates after discharge from psychiatric facilities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(7), 694–702.

Cotgrove, A., Zirinsky, L., Black, D., & Weston, D. (1995). Secondary prevention of attempted suicide in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 18(5), 569–577. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.1995.1039

Cox, L. J., Stanley, B. H., Melhem, N. M., Oquendo, M. A., Birmaher, B., Burke, A., Kolko, D. J., Zelazny, J. M., Mann, J. J., Porta, G., & Brent, D. A. (2012). A longitudinal study of nonsuicidal self-injury in offspring at high risk for mood disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 73(6), 821–828.

Czyz, E. K., King, C. A., & Biermann, B. J. (2019). Motivational interviewing-enhanced safety planning for adolescents at high suicide risk: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 48(2), 250–262.

Diamond, G. S., Wintersteen, M. B., Brown, G. K., Diamond, G. M., Gallop, R., Shelef, K., & Levy, S. (2010). Attachment-based family therapy for adolescents with suicidal ideation: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(2), 122–131.

Donaldson, D., Spirito, A., Arrigan, M., & Aspel, J. W. (1997). Structured disposition planning for adolescent suicide attempters in a general hospital: Preliminary findings on short-term outcome. Archives of Suicide Research, 3(4), 271–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811119708258279

Doupnik, S. K., Rudd, B., Schmutte, T., et al. (2020). Association of Suicide Prevention Interventions with subsequent suicide attempts, linkage to follow-up care, and depression symptoms for acute care settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(10), 1021–1030. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1586

du Roscoät, E., & Beck, F. (2013). Efficient interventions on suicide prevention: A literature review. Revue D’epidemiologie Et De Sante Publique, 61(4), 363–374.

Eskin, M., Ertekin, K., & Demir, H. (2008). Efficacy of a problem-solving therapy for depression and suicide potential in adolescents and young adults. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 32(2), 227–245.

Esposito-Smythers, C., Spirito, A., Kahler, C. W., Hunt, J., & Monti, P. (2011). Treatment of co-occurring substance abuse and suicidality among adolescents: A randomized trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(6), 728–739.

Fitzpatrick, K. K., Witte, T. K., & Schmidt, N. B. (2005). Randomized controlled trial of a brief problem-orientation intervention for suicidal ideation. Behavior Therapy, 36(4), 323–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7894(05)80114-5

Forte, A., Buscajoni, A., Fiorillo, A., Pompili, M., & Baldessarini, R. J. (2019). Suicidal risk following hospital discharge: A review. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 27(4), 209–216.

Fox, K. R., Bettis, A. H., Burke, T. A., Hart, E. A., & Wang, S. B. (2022). Exploring adolescent experiences with disclosing self-injurious thoughts and behaviors across settings. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 50(5), 669–681.

Fox, K. R., Huang, X., Guzmán, E. M., Funsch, K. M., Cha, C. B., Ribeiro, J. D., & Franklin, J. C. (2020). Interventions for suicide and self-injury: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials across nearly 50 years of research. Psychological Bulletin, 146(12), 1117–1145.

Fox, K. R., Huang, X., Linthicum, K. P., Wang, S. B., Franklin, J. C., & Ribeiro, J. D. (2019). Model complexity improves the prediction of nonsuicidal self-injury. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 87(8), 684–692.

Franklin, J. C., Ribeiro, J. D., Fox, K. R., Bentley, K. H., Kleiman, E. M., Huang, X., Musacchio, K. M., Jaroszewski, A. C., Chang, B. P., & Nock, M. K. (2017). Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychological Bulletin, 143(2), 187–232.

Glenn, C. R., Esposito, E. C., Porter, A. C., & Robinson, D. J. (2019). Evidence base update of psychosocial treatments for self-injurious thoughts and behaviors in youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 48(3), 357–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2019.1591281

Glenn, C. R., Franklin, J. C., & Nock, M. K. (2015). Evidence-based treatments for self- injurious thoughts and behaviors in youth. PsycEXTRA Dataset. https://doi.org/10.1037/e521702015-006

Goldston, D. B., Daniel, S. S., Reboussin, D. M., Reboussin, B. A., Frazier, P. H., & Kelley, A. E. (1999). Suicide attempts among formerly hospitalized adolescents: A prospective naturalistic study of risk during the first 5 years after discharge. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(6), 660–671.

Gonzales, A. H., & Bergstrom, L. (2013). Adolescent Non-Suicidal Self-Injury (NSSI) Interventions. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 26(2), 124–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcap.12035

Granboulan, V., Roudot-Thoraval, F., Lemerle, S., & Alvin, P. (2001). Predictive factors of post-discharge follow-up care among adolescent suicide attempters. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 104(1), 31–36.

Grupp-Phelan, J., Stevens, J., Boyd, S., Cohen, D., Ammerman, R., Liddy-Hicks, S., Heck, K., Marcus, S., Stone, L., Campo, J., & Bridge, J. (2019). Effect of a motivational interviewing-based intervention on initiation of mental health treatment and mental health after an emergency department visit among suicidal adolescents. JAMA Network Open, 2(12), e1917941. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.17941

Harpaz-Rotem, I., Leslie, D., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2004). Treatment retention among children entering a new episode of mental health care. Psychiatric Services, 55(9), 1022–1028.

Harris, L. M., Huang, X., Funsch, K. M., et al. (2022). Efficacy of interventions for suicide and self-injury in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Science and Reports, 12, 12313. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-16567-8

Hill, R. M., & Pettit, J. W. (2019). Pilot randomized controlled trial of LEAP: A selective preventive intervention to reduce adolescents’ perceived burdensomeness. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 48(S1), S45–S56. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2016.1188705

Hom, M. A., Stanley, I. H., & Joiner, T. E. (2015). Evaluating factors and interventions that influence help-seeking and mental health service utilization among suicidal individuals: A review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 40, 28–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.05.006

Husky, M. M., Olfson, M., He, J.-P., Nock, M. K., Swanson, S. A., & Merikangas, K. R. (2012). Twelve-month suicidal symptoms and use of services among adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Psychiatric Services, 63(10), 989–996.

Inagaki, M., Kawashima, Y., Yonemoto, N., & Yamada, M. (2019). Active contact and follow-up interventions to prevent repeat suicide attempts during high-risk periods among patients admitted to emergency departments for suicidal behavior: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 19, 44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2017-7

Kavalidoua, K., Smith, D. J., Der, G., & O’Connor, R. C. (2019). The role of physical and mental multimorbidity in suicidal thoughts and behaviours in a Scottish population cohort study. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1), 38.

Kennard, B. D., Goldstein, T., Foxwell, A. A., McMakin, D. L., Wolfe, K., Biernesser, C., Moorehead, A., Douaihy, A., Zullo, L., Wentroble, E., Owen, V., Zelazny, J., Iyengar, S., Porta, G., & Brent, D. (2018). As Safe as Possible (ASAP): A brief app-supported inpatient intervention to prevent postdischarge suicidal behavior in hospitalized suicidal adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry, 175(9), 864–872. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17101151

King, C. A., Arango, A., Kramer, A., Busby, D., Czyz, E., Foster, C. E., & Gillespie, B. W. (2019). Association of the youth-nominated support team intervention for suicidal adolescents with 11- to 14-year mortality outcomes: Secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(5), 492–498.

King, C. A., Gipson, P. Y., Horwitz, A. G., & Opperman, K. J. (2015). Teen options for change: An intervention for young emergency patients who screen positive for suicide risk. Psychiatric Services, 66(1), 97–100. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201300347

King, C. A., Klaus, N., Kramer, A., Venkataraman, S., Quinlan, P., & Gillespie, B. (2009). The youth-nominated support team-version II for suicidal adolescents: A randomized controlled intervention trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(5), 880–893.

King, C. A., Kramer, A., & Preuss, L. (2001). Youth-Nominated Support Team Manual. Retrieved from https://medicine.umich.edu/sites/default/files/downloads/YST%20Manual%202001.pdf

King, C. A., Kramer, A., Preuss, L., Kerr, D. C. R., Weisse, L., & Venkataraman, S. (2006). Youth-Nominated Support Team for Suicidal Adolescents (Version 1): A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(1), 199–206.

Kleiman, E. M., Turner, B. J., Fedor, S., Beale, E. E., Huffman, J. C., & Nock, M. K. (2017). Examination of real-time fluctuations in suicidal ideation and its risk factors: Results from two ecological momentary assessment studies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(6), 726–738.

Liu, R. T., Bettis, A. H., & Burke, T. A. (2020). Characterizing the phenomenology of passive suicidal ideation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of its prevalence, psychiatric comorbidity, correlates, and comparisons with active suicidal ideation. Psychological Medicine, 50(3), 367–383.

Lizardi, D., & Stanley, B. (2010). Treatment engagement: A neglected aspect in the psychiatric care of suicidal patients. Psychiatric Services, 61(12), 1183–1191.

McCabe, R., Garside, R., Backhouse, A., & Xanthopoulou, P. (2018). Effectiveness of brief psychological interventions for suicidal presentations: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 120.

Mehlum, L., Tørmoen, A. J., Ramberg, M., Haga, E., Diep, L. M., Laberg, S., Larsson, B. S., Stanley, B. H., Miller, A. L., Sund, A. M., & Grøholt, B. (2014). Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents with repeated suicidal and self-harming behavior: A randomized trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 53(10), 1082–1091.

Melhem, N. M., & Brent, D. (2020). Do brief preventive interventions for patients at suicide risk work? JAMA Psychiatry, 77(10), 997–999. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1287

Milner, A. J., Carter, G., Pirkis, J., Robinson, J., & Spittal, M. J. (2015). Letters, green cards, telephone calls and postcards: Systematic and meta-analytic review of brief contact interventions for reducing self-harm, suicide attempts and suicide. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 206(3), 184–190.

MindWise Innovations. (2018). SOS signs of Suicide® Parent Resources. Retrieved from https://sossignsofsuicide.org/parent

MindWise Innovations. (2022). SOS signs of suicide: Suicide prevention training for 6–12th grades. Retrieved from https://www.mindwise.org/sos-signs-of-suicide/

Mojtabai, R., Olfson, M., Sampson, N. A., Jin, R., Druss, B., Wang, P. S., Wells, K. B., Pincus, H. A., & Kessler, R. C. (2011). Barriers to mental health treatment: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychological Medicine, 41(8), 1751–1761.

Nestor, B. A., Cheek, S. M., & Liu, R. T. (2016). Ethnic and racial differences in mental health service utilization for suicidal ideation and behavior in a nationally representative sample of adolescents. Journal of Affective Disorders, 202, 197–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.021

Nock, M. K. (2010). Self-injury. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 339–363.

Nock, M. K., Borges, G., Bromet, E. J., Cha, C. B., Kessler, R. C., & Lee, S. (2008). Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiologic Reviews, 30, 133–154.

Nock, M. K., Green, J. G., Hwang, I., McLaughlin, K. A., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Kessler, R. C. (2013). Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(3), 300–310.

Ougrin, D., Boege, I., Stahl, D., Banarsee, R., & Taylor, E. (2013). Randomised controlled trial of therapeutic assessment versus usual assessment in adolescents with self-harm: 2-year follow-up. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 98(10), 772–776.

Pachankis, J. E. (2018). The scientific pursuit of sexual and gender minority mental health treatments: Toward evidence-based affirmative practice. American Psychologist, 73(9), 1207–1219. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000357

Perera, E. A., & Kathriarachchi, S. T. (2011). Problem-solving counseling as a therapeutic tool on youth suicidal behavior in the suburban population in Sri Lanka. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 53(1), 30–35. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.75558

Piacentini, J., Rotheram-Borus, M. J., Gillis, J. R., Graae, F., Trautman, P., Cantwell, C., Garcia-Leeds, C., & Shaffer, D. (1995). Demographic predictors of treatment attendance among adolescent suicide attempters. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63(3), 469–473.

Pineda, J., & Dadds, M. R. (2013). Family intervention for adolescents with suicidal behavior: A randomized controlled trial and mediation analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(8), 851–862.

Plemmons, G., Hall, M., Doupnik, S., Gay, J., Brown, C., Browning, W., Casey, R., Freundlich, K., Johnson, D. P., Lind, C., Rehm, K., Thomas, S., & Williams, D. (2018). Hospitalization for suicide ideation or attempt: 2008–2015. Pediatrics, 141(6), 2426. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-2426

Prinstein, M. J., Nock, M. K., Simon, V., Aikins, J. W., Cheah, C. S. L., & Spirito, A. (2008). Longitudinal trajectories and predictors of adolescent suicidal ideation and attempts following inpatient hospitalization. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(1), 92–103.

Rengasamy, M., & Sparks, G. (2019). Reduction of postdischarge suicidal behavior among adolescents through a telephone-based intervention. Psychiatric Services, 70(7), 545–552.

Ribeiro, J. D., Franklin, J. C., Fox, K. R., Bentley, K. H., Kleiman, E. M., Chang, B. P., & Nock, M. K. (2016). Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors as risk factors for future suicide ideation, attempts, and death: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Medicine, 46(2), 225–236. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291715001804