Abstract

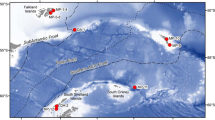

We report the invasion of the Gulf of Maine, in the northwest Atlantic Ocean, by the largest red seaweed in the world, the Asian Grateloupia turuturu. First detected in 1994 in Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island, south of Cape Cod, this alga had expanded its range in the following years only over to Long Island and into Long Island Sound. In July 2007 we found Grateloupia in the Cape Cod Canal and as far north (east) as Boston, Massachusetts, establishing its presence in the Gulf of Maine. Grateloupia can be invasive and may be capable of disrupting low intertidal and shallow subtidal seaweeds. The plant's broad physiological tolerances suggest that it will be able to expand possibly as far north as the Bay of Fundy. We predict its continued spread in North America and around the world, noting that its arrival in the major international port of Boston may now launch G. turuturu on to new global shipping corridors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Mathieson et al. (2003) noted that introduced seaweeds are a major problem throughout the world’s oceans, altering natural communities and sometimes causing significant economic losses. We here report the invasion of the Gulf of Maine, in the northwest Atlantic Ocean, by what has been described as the largest red seaweed in the world (Simon et al. 2001), the Asian Grateloupia turuturu Yamada (Halymeniales, Rhodophyta).

Grateloupia turuturu was first detected on the Atlantic coast of North America in 1994 in southern New England, when attached specimens were discovered south and west of Cape Cod, in Rhode Island (RI) in Narragansett Bay [Villalard Bohnsack and Harlin 1997, as G. doryphora (Montagne) Howe]. The plant’s elongate fronds are deep red to purple, up to 15 cm in width, almost a meter in length, and attached by a small discoid base (Fig. 1). In July 2007 we discovered that this alga had taken a major leap to the north and east of Cape Cod, a long-recognized biogeographic boundary between southern warmer and northern colder waters. Between 1994 and 2006, G. turuturu had expanded its range only along the shores of Narragansett Bay, to Long Island, and south into Long Island Sound (Pederson et al. 2005; Mathieson et al. 2008).

On July 25 and 26, 2007, during a Rapid Assessment Survey of float-pontoon fouling communities from Woods Hole, Massachusetts (MA) to Camden and Rockland in Penobscot Bay, Maine (ME), G. turuturu was discovered in small boat marinas at each end of the Cape Cod Canal and in Boston MA. On July 25 it was found growing on the submerged edges of floats at a marina at the southern (western) end of the Cape Cod Canal in Buzzards Bay, Bourne MA (31 ppt, 21°C) and at the northern (eastern) end of the Cape Cod Canal at Sandwich MA in Cape Cod Bay (31 ppt, 20°C). On July 26, G. turuturu was found in the inner harbor of the city of Boston, at Rowes Wharf (30.6 ppt, 19°C). The plant has not been found between Boston and Camden ME. The present northward extension of G. turuturu is an expansion of over 132 km in less than 4 years.

The Cape Cod Canal opened in 1914. Twelve kilometers in length, it is part of the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway, connecting Buzzards Bay to the south and west with Cape Cod Bay to the north and east. The role of canals in facilitating movement of seaweeds into new habitats is well established as shown by studies on the impact of the Suez Canal on the Mediterranean flora (Lüning 1990), which opened in 1869 and allowed a Lessepsian migration of at least 20 Indo-Pacific algal species and one seagrass from the Red Sea. The Cape Cod Canal has similarly allowed migration of both native and non-native species northward into the Gulf of Maine, including fish, barnacles, and other species (J. T. Carlton, unpublished). The movement of G. turuturu was very likely due to transport on boat hulls into and through the canal and into Boston, as was shown for vessel-mediated transport of Grateloupia in the Solent region of England (Farnham 1980) and the Brittany coast of France (Simon et al. 2001).

The Asiatic green alga Codium fragile (Suringar) Hariot subsp. tomentosoides (van Goor) P. C. Silva (now one of the most conspicuous introduced seaweeds of the Gulf of Maine) and the red alga Porphyra katadae Miura are two further examples of introduced seaweeds that have also been transported through the Cape Cod Canal (Carlton and Scanlon 1985; Mathieson et al. 2003; Neefus et al. 2007). Codium was first found on Long Island in 1957 and by the late 1960s it had migrated through the Canal to Cape Cod Bay (Carlton and Scanlon 1985). Porphyra katadae has been collected at three sites north of the canal in Cape Cod Bay and two locations south of the canal at Charlestown Beach RI and Buzzards Bay MA (Neefus et al. 2007).

Grateloupia turuturu is native to Japan and Korea (Gavio and Fredericq 2002; Guiry and Nic Dhonncha 2006), but now occurs in the Atlantic Ocean and the southern Pacific Ocean due to global shipping and mariculture activities. The seaweed was introduced into Narragansett Bay via ballast water or hull fouling either from Japan or Europe (Villalard-Bohnsack and Harlin 1997, 2001). Rhode Island populations of G. turuturu are genetically similar to European ones (Marston and Villalard-Bohnsack 2002).

Several authors (Saunders and Withall 2006; Verlaque et al. 2005; Villalard-Bohnsack and Harlin 1997, 2001) have suggested that G. turuturu can be invasive, and in particular may be capable of disrupting low intertidal and shallow subtidal seaweeds, including the abundant native alga Chondrus crispus Stackhouse (Harlin and Villalard-Bohnsack 2001) as seen in Figs. 2, 3. Grateloupia turuturu has the repertoire of an effective invader: it tolerates nutrient-enriched water, it grows well in 22–37 ppt, and it can survive 12–52 ppt and 4–28°C (Simon et al. 1999, 2001). The plant’s broad physiological tolerances suggest that it will be able to expand into the northerly parts of the Gulf of Maine and possibly the Bay of Fundy.

Grateloupia turuturu is undergoing rapid worldwide spread, having appeared recently not only in eastern North America but also in Tasmania (Saunders and Withall 2006) and Wellington Harbor, New Zealand (D’Archino et al. 2007). The former authors noted that efforts to determine the extent and distribution of the species should be implemented with the intent of limiting its further translocation and range expansion. We predict the continued spread of this seaweed both in North America and around the world, further noting that its arrival in the major international port of Boston may now launch G. turuturu on to new global shipping corridors.

References

Carlton JT, Scanlon JA (1985) Progression and dispersal of an introduced alga: Codium fragile subsp. tomentosoides (Chlorophyta) on the Atlantic Coast of North America. Botanica Marina 28:155–165

D’Archino R, Nelson WA, Zuccarello GCD (2007) Invasive marine red alga introduced to New Zealand water: first record of Grateloupia turuturu (Halymeniaceae, Rhodophyta). N Z J Mar Freshwater Res 41:35–42

Farnham WF (1980) Studies on aliens in the marine flora of southern England. In: Price JH, Irvine DEG, Farnham WF (eds) The shore environment, vol 2. Ecosystems. Academic Press, London, pp 875–914

Gavio B, Fredericq S (2002) Grateloupia turuturu (Halymeniaceae, Rhodophyta) is the correct name of the non-native species in the Atlantic known as Grateloupia doryphora. Eur J Phycol 17:349–359

Guiry MD, Nic Dhonncha E (2006) AlgaeBase version 3.0 World-wide electronic publication. National Univ. Ireland, Galway. (http://www.algaebase.org)

Harlin MM, Villalard-Bohnsack M (2001) Seasonal dynamics and recruitment strategies of the invasive seaweed Grateloupia doryphora (Halymeniaceae, Rhodophyta) in Narragansett Bay and Rhode Island Sound, Rhode Island, USA. Phycologia 40:468–474

Lüning K (1990) Seaweeds. Their Environment, Biogeography, and Ecophysiology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY. 527 pp

Marston M, Villalard-Bohnsack M (2002) Molecular variability and potential sources of Grateloupia doryphora (Halymeniaceae, Rhodophyta), an invasive species in Rhode Island waters (USA). J Phycol 38:659–658

Mathieson AC, Dawes CJ, Harris LG, Hehre EJ (2003) Expansion of the Asiatic green alga Codium fragile subsp. tomentosoides in the Gulf of Maine. Rhodora 105:1–53

Mathieson AC, Pederson J, Dawes CJ (2008) Rapid assessment surveys of fouling and introduced seaweeds in the northeastern Atlantic. Rhodora 110

Neefus CD, Mathieson AC, Bray TL (2007) The distribution, morphology, and ecology of three introduced Asiatic species of Porphyra (Bangiales, Rhodophyta) in the northeastern Atlantic. J Phycol (in press)

Pederson J, Bullock R, Carlton J, Dijkstra J, Dobroski N, Dyrynda P, Fisher R, Harris L, Hobbs N Lambert G, Lazo-Wasem E, Mathieson A, Miglietta M-P (2005) Marine Invaders in the Northeast. Rapid assessment survey of non-native and native marine species of float dock communities, August 2003. MIT Sea Grant College Program Publication No. 05–3, Cambridge, MA, 40 pp

Saunders GW, Withall RD (2006) Collections of the invasive species Grateloupia turuturu (Halymeniales, Rhodophyta) from Tasmania, Australia. Phycologia 45:711–714

Simon C, Gall EA, Levavasseur G, Deslandes E (1999) Effects of short-term variations of salinity and temperature on the photosynthetic response to the red alga Grateloupia doryphora from Brittany (France). Botanica Marina 42:437–440

Simon C, Gall EA, Deslandes E (2001) Expansion of the red alga Grateloupia doryphora along the coast of Brittany, France. Hydrobiologia 443:23–29

Verlaque M, Bannock PM, Komatsu T, Villalard-Bohnsack M, Marston M (2005) The genus Grateloupia C. Agardh (Halymeniaceae, Rhodophyta) in the Thau Lagoon (France, Mediterranean): a case study of marine plurispecific introductions. Phycologia 44:477–496

Villalard-Bohnsack M, Harlin M (1997) The appearance of Grateloupia doryphora (Halymeniaceae, Rhodophyta) on the northeast coast of North America. Phycologia 36:324–328

Villalard-Bohnsack M, Harlin M (2001) Grateloupia doryphora (Halymeniaceae, Rhodophyta) in Rhode Island waters (USA): geographic expansion, morphological variations and associated algae. Phycologia 40:372–380

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided from the Environmental Protection Agency (Grant X83055701), the Northeast Aquatic Nuisance Species Panel, in Maine by The Nature Conservancy, State Planning Office, Department of Marine Resources, Department of Environmental Protection, and Casco Bay Estuaries Project, in New Hampshire by the Estuaries Program and University of New Hampshire Marine Program, in Massachusetts by the Massachusetts Bay Program and the Coastal Zone Management Program, and by the Sea Grant College Programs of Connecticut, MIT, and Maine. Published as Scientific Contribution Number 2339 from the New Hampshire Agriculture Experiment Station, as well as Contribution Number 454 from UNH Jackson Estuarine Laboratory and Center for Marine Biology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Mathieson, A.C., Dawes, C.J., Pederson, J. et al. The Asian red seaweed Grateloupia turuturu (Rhodophyta) invades the Gulf of Maine. Biol Invasions 10, 985–988 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-007-9176-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-007-9176-z