Abstract

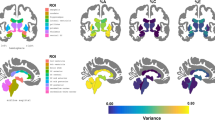

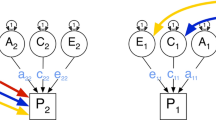

To study behavioral or psychiatric phenotypes, multiple indices of the behavior or disorder are often collected that are thought to best reflect the phenotype. Combining these items into a single score (e.g. a sum score) is a simple and practical approach for modeling such data, but this simplicity can come at a cost in longitudinal studies, where the relevance of individual items often changes as a function of age. Such changes violate the assumptions of longitudinal measurement invariance (MI), and this violation has the potential to obfuscate the interpretation of the results of latent growth models fit to sum scores. The objectives of this study are (1) to investigate the extent to which violations of longitudinal MI lead to bias in parameter estimates of the average growth curve trajectory, and (2) whether absence of MI affects estimates of the heritability of these growth curve parameters. To this end, we analytically derive the bias in the estimated means and variances of the latent growth factors fit to sum scores when the assumption of longitudinal MI is violated. This bias is further quantified via Monte Carlo simulation, and is illustrated in an empirical analysis of aggression in children aged 3–12 years. These analyses show that measurement non-invariance across age can indeed bias growth curve mean and variance estimates, and our quantification of this bias permits researchers to weigh the costs of using a simple sum score in longitudinal studies. Simulation results indicate that the genetic variance decomposition of growth factors is, however, not biased due to measurement non-invariance across age, provided the phenotype is measurement invariant across birth-order and zygosity in twins.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The observed scores in this derivation are assumed to be (multivariate) normally distributed.Categorical outcomes can be dealt with by a superseding threshold model (Agresti 2002), which is omitted here to avoid unnecessary complexity.

The item intercepts are fixed at zero to set them equal over time and also allow for the estimation of the intercept factor mean. Another option for SLGMs is to estimate item means and constrain them to equality over time while setting the intercept mean to zero.

As discussed above, the dimensions of \({\mathbf{\Theta }}\) are \((T*p) \times (T*p)\); in this case, \((4*6) \times (4*6)\), hence the need for a \(24~ \times ~24\) identity matrix here.

This “zygosity coefficient” is conventionally labeled \(\alpha ,\) but we use z so as not to confuse it with the label for the intercept factor.

References

Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA (2000) Manual for the ASEBA preschool forms & profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families. Burlington

Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA (2001) Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families. Burlington

Agresti A (2002) Categorical data analysis, 2nd edn, Wiley ser in probability and statistics, Hoboken

Bartels M, Hudziak JJ, van den Oord EJCG, van Beijsterveldt, CEM, Rietveld MJH, Boomsma DI (2003) Co-occurrence of aggressive behavior and rule-breaking behavior at age 12: Multi-rater analyses. Behav Genet 33(5):607–621

Bollen KA (1989) Structural equations with latent variables. Wiley, New York

Boomsma DI. (2015) Aggression in Children: Unravelling the interplay of genes and environment through (epi)genetics and metabolomics. J Ped Neo Ind Med. 4(2):e040251)

Boomsma DI, Molenaar PC (1987) The genetic analysis of repeated measures: I. simplex models. Behav Genet 17(2):111–123

Burt SA (2009) Are there meaningful etiological differences within antisocial behavior? results of a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 29(2):163–178

Byrne BM, Shavelson RJ, Muthén B (1989) Testing for the equivalence of factor covariance and mean structures: The issue of partial measurement invariance. Psychol Bull 105(3):456–466

Carmines EG, Zeller RA (1979) Reliability and validity assessment. Sage Publications, Newbury Park

Cronbach LJ (1951) Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16:297–334

Cui L, Colasante T, Malti T, Ribeaud D, Eisner MP (2016) Dual trajectories of reactive and proactive aggression from mid-childhood to early adolescence: Relations to sensation seeking, risk taking, and moral reasoning. J Abnorm Child Psychol 44(4):663–675

Edwards MC, Wirth RJ (2009) Measurement and the study of change. Res Hum Dev 6(2–3):74–96

Edwards MC, Wirth RJ (2012) Valid measurement without factorial invariance: A longitudinal example. In: Harring JR, Hancock GR (eds) Advances in longitudinal methods in the social and behavioral sciences. IAP Information Age Publishing, Charlotte, pp 289–311

Eley TC, Lichenstein P, Stevenson J (1999) Sex differences in the etiology of aggressive and nonaggressive antisocial behavior: results from two twin studies. Child Dev 70(1):155–168

Ferrer E, Balluerka N, Widaman KF (2008) Factorial invariance and the specification of second-order latent growth models. Methodology 4(1):22–36.

Finkel D, Davis DW, Turkheimer E, Dickens WT (2015) Applying biometric growth curve models to developmental synchronies in cognitive development: The Louisville twin study. Behav Genet 45(6):600–609

Forsman M, Lichtenstein P, Andershed H, Larsson H (2010) A longitudinal twin study of the direction of effects between psychopathic personality and antisocial behaviour. J Child Psychology. Psychiatry 51(1):39–47

George D, Mallery P (2005) SPSS for windows step by step: a simple guide and reference 12.0 update. 5th edn. Pearson Education New Zealand, Auckland

Goodman R (1997) The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip 38(5):581–586

Grimm KJ, Kuhl AP, Zhang Z (2013) Measurement models, estimation, and the study of change. Struct Equat Model 20(3):504–517

Hancock GR, Kuo W, Lawrence FR (2001) An illustration of second-order latent growth models. Struct Equat Model 8(3):470–489

Hudziak JJ, van Beijsterveldt CEM, Bartels M, Rietveld MJH, Rettew DC, Derks EM, Boomsma DI (2003) Individual differences in aggression: genetic analyses by age, gender, and informant in 3-, 7-, and 10-year-old dutch twins. Behav Genet 33(5):575–589

Kan K, Dolan CV, Nivard MG, Middeldorp CM, van Beijsterveldt CEM, Willemsen G, Boomsma DI (2013) Genetic and environmental stability in attention problems across the lifespan: evidence from the netherlands twin register. J Am Acad Child Adoles Psychiatry 52(1):12–25

Leite WL (2007) A comparison of latent growth models for constructs measured by multiple items. Struct Equat Model 14(4):581–610

Lubke GH, Neale MC, Dolan CV (2004) Implications of absence of measurement invariance for detecting sex limitation and genotype by environment interaction. Twin Res 7:292–298

Lubke GH, Miller PJ, Verhulst B, Bartels M, van Beijsterveldt CEM, Willemsen G, Boomsma DI, Middeldorp CM (2016) A powerful phenotype for gene-finding studies derived from trajectory analyses of symptoms of anxiety and depression between age seven and 18. Am J Med Genet B: Neuropsychiatric Genet 171(7):948–957

Lubke GH, McArtor DB, Boomsma DI, Bartels M (in press) Genetic and environmental contributions to the development of childhood aggression. Dev Psych

McArdle JJ (1986) Latent variable growth within behavior genetic models. Behav Genet 16(1):163–200

McArdle JJ (1988) Dynamic but structural equation modeling of repeated measures data. In: Nesselroade JR, Cattell RB (eds) 2nd edn. Handbook of multivariate experimental psychology. Plenum Press, New York, pp 561–614

McArdle JJ, Hamagami F (2003) Structural equation models for evaluating dynamic concepts within longitudinal twin analyses. Behav Genet 33(2):137–159

Meredith W (1993) Measurement invariance, factor analysis and factorial invariance. Psychometrika 58(4):525–543

Meredith W, Horn J (2001) The role of factorial invariance in modeling growth and change. In: Collins LM, Sayer AG (eds) New methods for the analysis of change. American Psychological Association, Washington, pp 203–240

Molenaar D, Dolan CV (2014) Testing systematic genotype by environment interactions using item level data. Behav Genet 44(3):212–231

Muthén LK, Muthén BO (1998–2015) Mplus user’s guide. Seventh Edition. Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles

Neale MC, Maes, HHM (2004) Methodology for genetic studies of twins and families. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York. Available at http://ibgwww.colorado.edu/workshop2006/cdrom/HTML/book2004a.pdf

Neale MC, McArdle JJ (2000) Structured latent growth curves for twin data. Twin Res 3(3): 165–177.

Neale MC, Lubke G, Aggen SH, Dolan CV (2005) Problems with using sum scores for estimating variance components: Contamination and measurement noninvariance. Twin Res Hum Genet 8(6):553–568

NICHD Early Child Care Research Network (2004) Trajectories of physical aggression from toddlerhood to middle childhood. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev 69(4):102–119

Porsch RM, Middeldorp CM, Cherny SS, Krapohl E, van Beijsterveldt CEM, Loukola A, Korhonen T, Pulkkinen L, Corley R, Rhee S et al (2016) Longitudinal heritability of childhood aggression. Am J Med Genet B 171(5):697–707

Prescott CA, Kendler KS (1996) Longitudinal stability and change in alcohol consumption among female twins: contributions of genetics. Dev Psychopathol 8(4):849–866

R Core Team (2017) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. URL http://www.R-project.org/

Rosseel Y (2012). lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. J Stat Software, 48(2):1–36. URL: http://www.jstatsoft.org/v48/i02/

Rutter M, Sroufe LA (2000) Developmental psychopathology: concepts and challenges. Dev Psychopathol 12(3):265–296

Sayer AG, Cumsille PE (2001) Second-order latent growth models. In: Collins LM, Sayer AG (eds) New methods for the analysis of change. American Psychological Association, Washington, pp 179–200

Schwabe I, van den Berg SM (2014) Assessing genotype by environment interaction in case of heterogeneous measurement error. Behav Genet 44(4):394–406. doi:10.1007/s10519-014-9649-7

Singer JD, Willett JB (2003) Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford University Press, New York

Slof-Op’t Landt MC, van Furth EF, Rebollo-Mesa I, Bartels M, van Beijsterveldt CEM, Slagboom PE, Boomsma DI, Meulenbelt I, Dolan CV (2009) Sex differences in sum scores may be hard to interpret: the importance of measurement invariance. Assessment 16(4):415–423

Tremblay RE (2003) Why socialization fails: The case of chronic physical aggression. In: Lahey BB, Moffitt TE, Caspi A (eds) Causes of conduct disorder and juvenile delinquency. Guilford Press, New York, pp 182–224

van Beijsterveldt CEM, Bartels M, Hudziak JJ, Boomsma DI (2003) Causes of stability of aggression from early childhood to adolescence: a longitudinal genetic analysis in dutch twins. Behav Genet 33(5):591–605

van Beijsterveldt, CEM, Groen-Blokhuis M, Hottenga JJ, Franić S, Hudziak JJ, Lamb D, Huppertz C, de Zeeuw E, Nivard M, Schutte N et al (2013) The young netherlands twin register (YNTR): longitudinal twin and family studies in over 70,000 children. Twin Res Hum Genet 16(1):252–267

van den Berg SM, Glas CAW, Boomsma DI (2007) Variance decomposition using an IRT measurement model. Behav Genet 37(4):604–616

van der Valk JC, Verhulst FC, Neale MC, Boomsma DI (1998) Longitudinal genetic analysis of problem behaviors in biologically related and unrelated adoptees. Behav Genet 28(5):365–380

Wang P, Niv S, Tuvblad C, Raine A, Baker LA (2013) The genetic and environmental overlap between aggressive and non-aggressive antisocial behavior in children and adolescents using the self-report delinquency interview (SR-DI). J Crim Justice 41(5):277–284

Widaman KF, Reise SP (1997) Exploring the measurement invariance of psychological instruments: Applications in the substance use domain. editors. In: Bryant KJ, Windle M, West SG (eds) The science of prevention: Methodological advances from alcohol and substance abuse research. American Psychological Association, Washington, pp 281–324

Widaman KF, Ferrer E, Conger RD (2010) Factorial invariance within longitudinal structural equation models: Measuring the same construct across time. Child Development. Perspectives 4(1):10–18

Wirth RJ. 2009. The effects of measurement non-invariance on parameter estimation in latent growth models. (Order No. AAI3331053)

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge grant FP7-602768 “ACTION: Aggression in Children: Unraveling gene-environment interplay to inform Treatment and InterventiON strategies” from the European Commission/European Union Seventh Framework Program. GL was in addition supported by DA-018673. The Netherlands Twin Register is supported by multiple grants from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) and MagW/ZonMW (Grants 904-61-090, 985-10-002, 904-61-193, 480-04-004, 400-05-717, 463-06-001, 451-04-034, Middelgroot-911-09-032).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Justin M. Luningham, Daniel B. McArtor, Meike Bartels, Dorret I. Boomsma, and Gitta H. Lubke declares they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study and/or from their parents.

Additional information

Edited by Deborah Finkel.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Under the assumption that the SLGM is the true data-generating model, summing the individual items at each time point results in a score that is a function of underlying factor loadings as well as the proposed growth in the factor. As an example, consider sum scores of 4 time points. A more explicit formulation of Eq. (9) is then,

In practice, fitting a univariate LGM to the sum score results in,

where \({{\mathbf{\upmu }}_{\mathbf{s}}}\) is inflated relative to \({\mathbf{\upmu }}\) as a function of the summed factor loadings and \({{\mathbf{\upvarepsilon }}_{{\mathbf{s}}i}}\) is the sum of \(p\) item residuals at each measurement occasion.

Appendix 2

Bias derivations

Bias is first evaluated in the means of the growth factors. Although the focus is on linear growth, these derivations could be extended to curvilinear growth. Recall that Eq. (6) gives \(~E\left[ {{{\mathbf{y}}_i}} \right]={\mathbf{\Lambda \Gamma \upmu }}\) because the item intercepts \({\mathbf{\upnu }}\) are set to 0 without loss of generality and \(E\left[ {{{\mathbf{\upxi }}_i}} \right]=~{\mathbf{\upmu }}={\text{~}}\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\mu _\alpha }}&{{\mu _\beta }} \end{array}} \right]'\). After pre-multiplying both sides of Eq. (6) with transposed loading matrices, the growth factor means can be isolated by pre-multiplying with \(\left( \mathbf{\Gamma ^{'} \Lambda ^{'} \Lambda \Gamma } \right)^{{ - 1}}\),

As described in the text, a fitted model may include some constrained factor loading matrix \({\mathbf{\tilde{\Lambda }}}\), but \(E\left[ {{{\mathbf{y}}_i}} \right]~\)is invariant to the constraints of \({\mathbf{\tilde{\Lambda }}}\), giving Eq. (11). This result generalizes to any form of \({\mathbf{\tilde{\Lambda }}}\), and the bias can be computed for the comparison of any misspecified measurement model to a known population value of \({\mathbf{\Lambda }}\).

Similarly, an expression that calculates the variance of the parameter estimates from constrained measurement models can be derived. Equation (7) establishes that the variance in the SLGM model is \({\mathbf{\Sigma }}_{y} = {\mathbf{\Lambda }}({\mathbf{\Gamma \Phi \Gamma ^{\prime}}} + {\mathbf{\Psi }}){\mathbf{\Lambda ^{\prime}}} + {\mathbf{\Theta }}.\) To solve for \({\mathbf{\Phi }}\), pre- and post-multiply both sides by the factor and growth loading matrices as follows,

By replacing \({\mathbf{\Lambda }}\) with the constrained loading matrix \({\mathbf{\tilde{\Lambda }}}\), \({\mathbf{\hat{\Phi }}}\) can be obtained,

Again, it is important to note that the \({\mathbf{\Lambda }}\)’s in the middle parentheses are not the constrained \({\mathbf{\tilde{\Lambda }}}\)’s. These represent the population-level covariance structure, which needs to be assumed or fixed to evaluate the bias of a misspecified measurement model.

Now consider the form of \({\mathbf{\tilde{\Lambda }}}\) when fitting a univariate LGM to unweighted sums of items at each time point. The univariate model simply applies the linear growth function to one value at each time point, and the underlying individual item loadings \({\lambda _{jt}}\) are no longer considered once the items are summed to form \({{\mathbf{y}}_{{{\mathbf{s}}_i}}}\). Therefore, the univariate model treats the constrained loading matrix \({\mathbf{\tilde{\Lambda }}}\) essentially as an identity matrix. This results in fitting the univariate growth model of Eq. (1) to the aggregated sums of multiple items at each time point,

where \({\mathbf{S}}{{\mathbf{S}}_i}\) is the aforementioned vector of sum scores for individual \(i\) and \({\mathbf{\hat{\upmu }}}_{{\mathbf{s}}}\) is a vector of intercept and slope means estimated when the univariate model is fit to the sum scores. The derivation for the estimated intercept and slope means for the sum score then has the form,

with the true form of \(E[{\mathbf{S}}{{\mathbf{S}}_i}]\) given by Eq. (9) under the assumption that the true data-generating process is actually the SLGM for the item-level data. The estimated intercept and slope covariance matrix is similarly derived for sum scores, where \({\mathbf{\tilde{\Lambda }}}\) is treated as identity from Eq. (13) and \({{\mathbf{\Lambda }}_{\mathbf{s}}}\) from Eq. (9) is the population-level \({\mathbf{\Lambda }}\) for the summed items, giving,

Appendix 3

The measurement loading matrices that were used in the analytic demonstrations are given below:

These correspond to the description of the three scenarios described in the text.

Appendix 4

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Luningham, J.M., McArtor, D.B., Bartels, M. et al. Sum Scores in Twin Growth Curve Models: Practicality Versus Bias. Behav Genet 47, 516–536 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-017-9864-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-017-9864-0