Abstract

Despite well-documented individual, relational, and health benefits, masturbation has been stigmatized and is understudied compared to partnered sex. In a US nationally representative survey of adults, we aimed to: (1) assess the prevalence and frequency of participants’ prior-year masturbation, (2) describe reasons people give for not masturbating, (3) describe reasons people give for masturbating, and (4) examine the association between masturbation frequency and actual/desired partnered sex frequency in the prior year. Significantly more men than women reported lifetime masturbation, past month masturbation, and greater masturbation frequency. The most frequently endorsed reasons for masturbating related to pleasure, feeling “horny,” stress relief, and relaxation. The most frequently endorsed reasons for not masturbating were lack of interest, being in a committed relationship, conflict with morals or values, or being against one’s religion. Among women, those who desired partnered sex much more often and a little more often were 3.89 times (95% CI: 2.98, 5.08) and 2.07 times (95% CI: 1.63, 2.62), respectively, more likely to report higher frequencies of past-year masturbation than those who desired no change in their partnered sex frequency. Among men, those who desired partnered sex much more often and a little more often were 4.40 times (95% CI: 3.41, 5.68) and 2.37 times (95% CI: 1.84, 3.06), respectively, more likely to report higher frequencies of past-year masturbation activity than those who reported that they desired no change in their current partnered sex frequency. Findings provide contemporary U.S. population-level data on patterns of adult masturbation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the field of public health, sexual behavior data are routinely collected in U.S. nationally representative surveillance surveys including the National Survey of Family Growth, Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey, and National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention [CDC], n.d., 2022a, 2022b). Assessing population-level sexual behaviors helps to benchmark behaviors, examine trends over time, and provides data for age-appropriate sexuality education curricula. In a 2012 inventory of nationally representative surveys and surveillance systems, CDC researchers noted that sexual health behavior data from such surveys can help to characterize normative and evolving sexual health behaviors as well as inform policy development and age-appropriate prevention programs (Ivankovich et al., 2013). However, these surveys focus their assessment on partnered sex behaviors, given their risk for public health outcomes of interest such as STIs and unintended pregnancy (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, nd, 2022a, 2022b). Masturbation is rarely addressed in broader public health surveillance studies, leaving surveys that focus specifically on sexual behavior to assess its prevalence, frequency, and correlates.

Solo masturbation is a common form of sexual expression across the lifespan, without risk of pregnancy or sexually transmitted infections (STI), and regardless of partner availability or interest (Coleman, 2003; Dekker & Schmidt, 2003; Robbins et al., 2011). Masturbation can help people explore their sexuality, experience pleasure, and learn about their bodily responses in ways that may support healthy sexual development, self-esteem, and body positivity (Coleman, 2003; Kaestle & Allen, 2011; Rowland et al., 2020). Indeed, masturbation is often included as part of therapeutic treatment plans for sexual difficulties, such as premature ejaculation and anorgasmia (Laan & Rellini, 2011; Rodriguez & Lopez, 2016; Riley & Segraves, 2006; Rullo et al., 2018). Despite these well-documented individual, relational, and health benefits, masturbation has been stigmatized (particularly for women), prohibited, and remains understudied in comparison with research on partnered sex (Baćak & Štulhofer, 2011; Bullough, 2003; Das, 2007; Fahs & Frank, 2014; Perry, 2019; Younis et al., 2018), reflecting far less scientific attention to how people behave sexually with themselves than with other people.

Prevalence and Frequency of Masturbation

Masturbation is prevalent in countries around the world including Australia, China, Croatia, Denmark, Finland, Germany, the UK, and the USA (Baćak & Štulhofer, 2011; Burri & Carvalheira, 2019; Das et al., 2009; Gerressu et al., 2008; Haavio-Mannila et al., 2003; Hald, 2006; Herbenick et al., 2010; Lindau et al., 2018; Richters et al., 2014). More men than women report lifetime masturbation and recent masturbation; also, men report more frequent masturbation as compared to women (Gerressu et al., 2008; Herbenick et al., 2010; Oliver & Hyde, 1993; Petersen & Hyde, 2011). In the 2009 National Survey of Sexual Health Behavior (NSSHB), a U.S. nationally representative survey of 5865 men and women ages 14–94, 28% of men ages 70 + , 43% of men ages 14–15 and 60–69, and more than half of men ages 16–59 reported having engaged in solo masturbation in the prior month (Herbenick et al., 2010). Twenty percent of women across the lifespan reported solo masturbation in the prior month (with rates exceeding 40% only for women ages 20–29), with 12% of women over 70 years of age reporting past-month masturbation (Herbenick et al., 2010). More recently, in a comparison of sexual behaviors reported in the 2009 and 2018 waves of the NSSHB, although all forms of partnered sex assessed had decreased from 2009 to 2018, solo masturbation among adults did not decline during this time frame (Herbenick et al., 2022).

Since that time, the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted daily life around the world. Some studies have shown an increase in solo masturbation toward the beginning of the pandemic (Gleason et al., 2021), though population-level data are needed. As close contact with infected individuals can increase the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission, public health agencies have recommended changes to many activities of daily life, including sex. These have included identifying safer ways to be sexual, such as solo masturbation and technology-mediated sexual activities (e.g., video-based sex) (Elliott, 2020; NYC Health Department, 2021; San Francisco Department of Public Health, 2021). Thus, consistent with public health disciplinary norms around behavioral surveillance, a goal of the present research was to document masturbation rates during the COVID-19 pandemic as well as to understand whether some people were choosing to masturbate as a form of SARS-CoV-2 risk reduction efforts.

Reasons for Masturbating and Not Masturbating

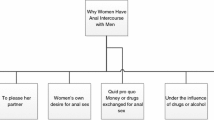

Common reasons people give for masturbating include to release sexual tension, feel sexual pleasure, experience orgasm, learn about their body, help fall asleep, love oneself, and because they’re having less partnered sex than they’d like (Bowman, 2014; Dodson, 1987; Fahs & Frank, 2014; Regnerus et al., 2017; Rowland et al., 2020). Frequently endorsed reasons for not masturbating include lack of privacy, religious and cultural shame, stigma, and partner disapproval, among others (Carvalheira & Leal, 2013; Cito et al., 2021; Kaestle & Allen, 2011; Lester et al., 2016; Walsh, 2000). Solo masturbation has been prohibited in some religions, leading to internal conflict related to desires to masturbate (Bullough, 2003; Chowdhury et al., 2019; Hungrige, 2016). Also, pervasive social stigma and medical misinformation have often described masturbation as detrimental to human health, contributing to some people’s concerns about whether masturbating is acceptable (Laqueur, 2003). However, research on reasons for, and for not, masturbating are largely from convenience or clinical samples. The present research extends the literature by devoting greater attention to people’s experiences with masturbation, by examining their reasons for masturbating—as well as for not masturbating—within a U.S. nationally representative survey.

Solo Masturbation in the Context of Intimate Relationships

Although solo masturbation is a valid sexual behavior in its own right, researchers frequently consider it in relation to partnered sex, proposing compensatory and complementary models of masturbation. The compensatory model suggests an inverse relationship between solo masturbation and partnered sex, proposing that a major reason people masturbate is to make up for a lack of partnered sex (Gerressu et al., 2008; Regnerus et al., 2017). In a sense, the compensatory model suggests that solo masturbation “competes” with partnered sex; that is, a person may only have so much desire, built up sexual tension, or capacity for sex. Thus, masturbation may dampen interest in, or motivation for, partnered sex. In contrast, the complementary model of masturbation suggests a positive interplay between masturbation and partnered sex. In this view, masturbation may increase desire for, or pleasures experienced from, partnered sex; additionally, partnered sex may increase desire for, or enjoyment of, masturbation (Regnerus et al., 2017). Evidence supports each of these models; indeed, the relationship between solo masturbation and partnered sex is likely complex, influenced by individual and relationship characteristics, religiosity, culture, privacy, and sexual agency (Carvalheira & Leal, 2013; Das, 2007; Das et al., 2009; Fischer et al., 2021; Gerressu et al., 2008; Regnerus et al., 2017; Robbins et al., 2011). The present study provides an opportunity to examine the relationship between individuals’ masturbation experience and partnered experiences.

Aims

The aims of the present research were to, in a U.S. nationally representative survey of adults, (1) assess the prevalence and frequency of participants’ prior-year masturbation, (2) describe the reasons people give for not masturbating, (3) describe the reasons people give for masturbating, and (4) examine the association between masturbation frequency and actual/desired partnered sex frequency in the prior year. Also, we hypothesized that significantly more young adults, as compared to older adults, would endorse masturbation as a form of risk reduction during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Method

Participants

The Institutional Review Board at the first author’s university reviewed and approved measures and protocols associated with the research. Data were from the 2021 National Survey of Sexual Wellbeing, a U.S. nationally representative survey of adults ages 18 and over (with no upper age limit for sampling). Funding for this study was provided by Roman Health Ventures, LLC (see acknowledgements). Individuals were recruited in May and June 2021 from the Ipsos KnowledgePanel®, which is a probability-based online panel. During this time period, COVID vaccines were available to most adults though COVID-19 safety guidance (e.g., masking, physical distancing, restrictions on capacity and crowd) varied widely within the USA. The Ipsos KnowledgePanel® has been used for numerous U.S. nationally representative surveys including on topics related to health and sexuality (Fu et al., 2021; Primack et al., 2017; Raifman et al., 2021; Rowen et al., 2016).

The KnowledgePanel® is developed by Ipsos and is by invitation-only (i.e., one cannot “opt-in” to the panel). Ipsos uses address-based sampling methodologies and the U.S. Postal Service’s Delivery Sequence File to identify and invite people into the KnowledgePanel®. That is, Ipsos randomly selects households and then uses mailings and follow-up phone calls to invite people to join the panel. If a selected household does not have Internet connectivity, they are offered connectivity to facilitate panel participation. KnowledgePanel® members may earn points for survey participation; they can accumulate points over time and exchange them for cash or merchandise. As part of recruitment and retention efforts, KnowledgePanel® members respond to questions about their background and demographics; these data become part of their profile data and are included in a de-identified dataset sent to the research team (i.e., the researchers never have access to participants’ names or other identifiers).

For this survey, Ipsos identified a sampling frame of 7138 adult KnowledgePanel® members ages 18 and over and sent them a recruitment email to let them know that a survey was available to complete. Of these, 4375 individuals visited the page, reviewed the consent form, indicated their consent to participate, and completed at least some of the survey (61.2% partial response rate); 3878 proceeded to the end of the survey and are included in the analytic dataset (54.3% complete response rate). The survey was confidential, cross-sectional, conducted online, and the median completion time was 16.1 min. To correct for non-response or under/over-coverage, Ipsos developed statistical weights using the March 2020 supplement of the Current Population Survey and demographic variables (gender, age, race/ethnicity, education, household income, U.S. Census region). Weighted data were used for all analyses presented herein.

Measures

Demographic Characteristics

These include age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, annual household income, sexual identity (bisexual, gay or lesbian, heterosexual or straight, pansexual, asexual, let me describe), relationship status (single and not dating, single and dating or hooking up, in one romantic relationship, in more than one romantic relationship). See Table 1 for full list and response options. For gender, we asked participants “When we analyze data by gender/sex, which category should we include you in?” (Response options were: women, men, gender nonbinary, transgender women or transfeminine, transgender men or transmasculine, let me describe).

Recency of Masturbation

Using an item from the 2009 NSSHB (Herbenick et al., 2010), participants were asked, “How recently have you masturbated alone (stimulated your body for sexual pleasure, whether or not you had an orgasm)?” Response options were: past month, past year, more than a year ago, never.

Past Year Masturbation Frequency

Using an item from the 2009 NSSHB, participants were asked: “Thinking about the past year, about how often have you masturbated by yourself?” Response options were: not at all, a few times in the past year, once a month, a few times per month, once a week, 2–3 times per week, almost every day. Past year masturbation frequency was recoded to the following categories due to smaller cell counts: not at all, less than once a month, once a month, more than once a month, more than once a week.

Reasons for Not Masturbating

Participants who reported not having masturbated in the prior year were asked, “What are the reason(s) you haven’t masturbated this year?” We selected 12 items from the 62-item Reasons for Avoiding Masturbating subscale (Young & Muehlenhard, 2011), such as related to religion, lack of interest, lack of privacy, feeling it’s bad for one’s health, among others. See Table 2 for full list of reasons assessed.

Reasons for Masturbating

Participants who reported having masturbated in the prior year were asked, “What are the main reasons you masturbate?” A subset of 13 reasons for masturbating were selected from the 72-item Reasons for Wanting to Masturbate subscale of the Attitudes Toward Masturbation Scale (Young & Muehlenhard, 2011), such as related to pleasure, wanting to relax, relieving stress, among others. We added a new reason which was “Due to COVID-19, it seems safer to masturbate than have sex with people that could put me at risk” as this sentiment had been voluntarily expressed (unprompted) by some college students enrolled in the first author’s human sexuality course. See Table 3 for full list of reasons assessed.

Prior Year Partnered Sex Frequency

Using an item modified from the 2009 and 2018 NSSHB (Herbenick et al., 2022) we asked participants, “Thinking about the past year, how often have you had sex with a partner (whatever you and your partner think of as “sex”—for example, mutual masturbation, sex toy use, oral sex, vaginal sex, or anal sex)?” Response options were: Not at all, a few times in the past year, once a month, a few times per month, once a week, 2–3 times per week, almost every day. Prior year partnered sex frequency was recoded to the following categories due to smaller cell counts: not at all, less than once a month, once a month, more than once a month, more than once a week.

Desired Partnered Sex Frequency

We created a new item for this survey based in part on an item from the British National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Wellings et al., 2019). We asked participants, “Would you prefer to have sex with a partner…?” Response options were: much more often than you do, a little more often than you do, no change—this is the right frequency for you, a little less often than you do, much less often than you do. Desired partnered sex frequency was re-coded into these categories: no change—right frequency; much more often; a little more often; less often.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted using the statistical software Stata version 15 (StataCorp, 2017). Those who had missing masturbation data were excluded from analyses. Weighted demographic and relationship characteristics, masturbation history, and reasons for masturbating and not masturbating in the past year are presented by gender; chi-squared tests were used to identify statistically significant gender differences. Ordinal logistic regression was used to identify statistically significant predictors of the recency of masturbation and past-year masturbation frequency. Potential predictors that were statistically significantly associated with masturbation in bivariate analyses were included in the adjusted models. Ordinal logistic regression models were also conducted to examine the association between actual/ideal partnered sex frequency and masturbation frequency in the past year. Demographic and relationship characteristics that were significantly associated with past-year masturbation frequency in bivariate analyses were included as covariates in the final adjusted model.

Results

A weighted total of 1958 women and 1784 men were included in the analysis (28 individuals, or 0.8% of the sample, identified as transgender women, transgender men, or gender non-binary). We present descriptive data for the gender diverse participants; however, the gender diverse sample sizes were insufficient for subsequent predictive analyses. The mean age of participants was 48.3 years (SD = 16.6; range = 18–92) for women and 48.1 years (SD = 18.3; range = 18–93) for men; approximately 30% of the sample was 60 years old or older. Most participants were non-Hispanic white (62.6% women, 64.0% men), heterosexual (87.7% women, 91.0% men), and in one romantic relationship (71.1% women, 70.6% men) (Table 1). Men reported a higher annual household income than women, and more women reported an LGBQ + sexual identity than men. Past year partnered sex frequency was similar between genders, with 34.3% of respondents reporting no partnered sex at all in the past year, and 5.0% reporting partnered sex almost every day. Desired partnered sex frequency was significantly greater among men compared to women; 40.7% of men reported desiring partnered sex much more often while only 21.4% of women reported the same.

Solo Masturbation

Both masturbation recency and masturbation frequency differed significantly by gender. In terms of recency, approximately 60% of men reported engaging in masturbation in the prior month as compared to 36.5% of women. Also, about one-quarter of women reported never having engaged in solo masturbation compared with 10.4% of men. For gender nonbinary participants, 11 indicated they had masturbated in the prior month and 1 indicated having never masturbated. Also, 5 of 6 transgender women reported having masturbated in the prior month. Of the transgender men, 7 had masturbated in the prior month, 2 had masturbated in the prior year, and 1 had never masturbated.

Masturbation frequency in the past year was significantly higher among men compared to women. For example, 35.9% of men and 8.8% of women reported having masturbated at least once a week in the prior year. Two of the gender nonbinary participants reported masturbating almost every day, five had masturbated 2–3 times per week, 1 had masturbated about once a week, and two a few times per month. For transgender women, 1 had masturbated almost every day, 3 masturbated 2–3 times per week, and 1 masturbated a few times per month. For transgender men, 3 masturbated almost every day, 3 masturbated 2–3 times per week, 1 masturbated once a week, and 3 masturbated once a month.

Reasons for Not Masturbating in the Prior Year

As shown in Table 2, among the reasons for not masturbating in the past year, the most common was “I’m just not interested” (68.7% women, 49.1% men) followed by “I’m in a committed relationship” (12.6% women, 20.2% men). Also, 8% of women and 9% of women indicated that they didn’t masturbate because it is against their religion. Fewer than 5% of participants indicated that they didn’t masturbate due to feeling uncomfortable with their body, lack of privacy, a belief that masturbation is bad for one’s health, feeling like they’re cheating on their partner, because their partner doesn’t want them to, feeling bad about themselves afterward, or because they’re trying to stop watching pornography.

Women were significantly more likely than men to report lack of interest and discomfort with one’s body as reasons for not masturbating in the past year. Men were significantly more likely than women to report not masturbating in the past year due to partner-related reasons (i.e., being in a committed relationship, feeling it would bother their partner if they knew, and because their partner doesn’t want them to masturbate). Men were also more likely to indicate they didn’t masturbate because they felt it was bad for their health and for “other reasons,” which they wrote in as old age, feeling satisfied by their partner, health issues, erection problems, spouse passed away, and preferring partnered sex.

Of the gender diverse participants, 1 of 12 gender nonbinary individuals, 0 of 6 transgender women, and 1 of 11 transgender men reported not masturbating in the prior year. The gender nonbinary participant indicated they were just not interested. The transgender man endorsed reasons related to lack of privacy, lack of interest, being against his religion, feeling bad about his body, as well as the relational reasons (feeling like they’re cheating, partner does not want them to).

Reasons for Masturbating in the Prior Year

As shown in Table 3, among the reasons surveyed for masturbating in the past year, the most common reasons selected were: “I find it pleasurable” (63.6% women, 65.6% men), “If I’m feeling horny” (49.0% women, 54.3% men), “To relieve stress” (36.2% women 36.7 men), “If I want to relax” (25.8% women, 26.6% men), and “To help me fall asleep” (25.7% women, 21.4% men). Fewer than 5% of participants indicated they had masturbated to be safer due to the COVID-19 pandemic or because their partner wants them to masturbate.

Women were significantly more likely than men to endorse “To help me fall asleep” and “To explore my own sexuality” as reasons for masturbating in the past year. Reasons volunteered by participants included not having a partner, not having enough partnered sex, feeling that masturbation is a safer sexual behavior during pregnancy, reading erotica or watching porn, wanting to, and health-related reasons (e.g., prostate health, pain relief, partner has pain during sex), among others. Men were more significantly likely than women to endorse the following reasons for masturbating in the past year: “If there is nothing else to do,” “If I’m feeling horny,” “If I’m not getting as much sex as I want,” “I enjoy my fantasies during masturbation,” “Because—even though I try—I just can’t stop myself,” “If I’m so aroused that it is interfering with other things I want or need to do,” and “Other reasons.”

Of the gender diverse participants, 11 of 12 gender nonbinary individuals, 5 of 6 transgender women, and 10 of 11 transgender men provided reasons for masturbating in the prior year. Common reasons were related to pleasure (11 of 12 nonbinary participants; 5 of 6 transgender women; and 2 of 7 transgender men); feeling horny (11 nonbinary, 4 transgender woman, 8 transgender men); to fall asleep (6 nonbinary, 1 transgender woman, 4 transgender men); not getting as much partnered sex as desired (4 nonbinary, 2 transgender men); relaxation (3 nonbinary, 1 transgender woman, 3 transgender men); enjoying fantasies (3 nonbinary, 2 transgender women, 5 transgender men); stress relief (8 nonbinary, 2 transgender women, 3 transgender men); inability to stop oneself (2 transgender men); sexual frustration (4 nonbinary); sexual exploration (1 transgender woman); due to partner wanting it (none); arousal interferes with other things (4 nonbinary, 3 transgender men); nothing else to do (4 nonbinary, 1 transgender woman, 1 transgender man); seems safer due to COVID-19 (2 nonbinary participants).

As shown in Supplementary Table 1, our hypothesis related to masturbation as a COVID risk reduction strategy was supported, though men’s reports drove this trend. Age differences were observed among men but not women for those who endorsed “Due to COVID-19, it seems safer to masturbate than to have sex with people that could put me at risk” as a reason for having masturbated in the prior year. Specifically, 10.2% of 18–24 year-olds men endorsed this reason compared to 2–5% of men in older age categories (p = 0.002). Among women, 5.6% of 18–24 year-olds endorsed this reason as did 0–5% of women in older age categories (p = 0.106).

Predictors of the Recency of Masturbation and Past-Year Masturbation Frequency

Participants who were younger, who were men, and with a higher education, a higher annual household income, and a non-heterosexual sexual identity were more likely to report both more recent and more frequent masturbation after adjusting for other covariates in the table (Table 4). Older age and those who reported a race/ethnicity of black, non-Hispanic or other, non-Hispanic (as compared to white participants) were less likely than white participants to report more recent masturbation. For masturbation frequency, these same demographic characteristics predicted less frequent masturbation in the prior year as did being in a current romantic relationship.

Masturbation, Partnered Sex Frequency, and Desired Partnered Sex Frequency

A statistically significant association was observed between actual partnered sex frequency and masturbation frequency in the past year among women but not men; women who reported higher partnered sex frequency reported more frequent masturbation (Table 5). Desired partnered sex frequency was associated with masturbation frequency in the past year for men and women; those who desired partnered sex more often were more likely than those who reported no change (right frequency) to report more frequent past-year masturbation activity. Among women, after adjusting for age, race/ethnicity, education, annual household income, sexual identity, and current relationship status, those who desired partnered sex much more often and a little more often were 3.89 times (95% CI: 2.98, 5.08) and 2.07 times (95% CI: 1.63, 2.62), respectively, more likely to report higher frequencies of past-year masturbation activity than those who reported that they desired no change in their current partnered sex frequency. Among men, after adjusting for other covariates, those who desired partnered sex much more often and a little more often were 4.40 times (95% CI: 3.41, 5.68) and 2.37 times (95% CI: 1.84, 3.06), respectively, more likely to report higher frequencies of past-year masturbation activity than those who reported that they desired no change in their current partnered sex frequency.

Discussion

Our study provides contemporary U.S. population estimates on past-year masturbation prevalence and frequency, given that the last published estimates of masturbation were more than a decade old. We extend the literature by providing U.S. nationally representative data on reasons for, and reasons for not, masturbating, as previous studies that addressed masturbation reasons were limited to convenience samples. Consistent with prior nationally representative surveys in various countries (Das et al., 2009; Gerressu et al., 2008; Herbenick et al., 2010; Richters et al., 2014), significantly more men than women in our study reported ever having masturbated, having masturbated recently (in this case, in the past month), and masturbating more often. Given the variation between studies in terms of ages surveyed and how data are presented, we are unable to make direct comparisons in terms of proportions or rates. However, the overall pattern of men reporting greater prevalence, frequency, and recency of masturbation remains. Researchers have speculated that such gender differences may be explained by differences in sex drive or may be due to gender differences in traditional sexual scripts that normalize masturbation among boys and men while repressing or stigmatizing it among girls and women (Baumeister et al., 2001; Fischer & Traeen, 2022; Haus & Thompson, 2020). Certainly, this study confirms how common masturbation or not masturbating is among men and women despite the differences between the genders. This helps demystify the myths and misinformation about this stigmatized sexual behavior which is so often a source of guilt and shame (Coleman, 2003; Das, 2007).

A unique contribution of our study is that, in a US nationally representative survey, we examined reasons for, and reasons for not, masturbating in the prior year. In terms of reasons for not masturbating, the most common reasons endorsed were that participants were just not interested (significantly more women than men), they were in a committed relationship (significantly more men than women), or that it was against their morals, values, or religion. Another reason selected by more women than men pertained to feeling uncomfortable with one’s body, though even this was selected by relatively few women. Although our study did not examine the specific contributors to discomfort with one’s body, prior research has found that poor body image may interfere with both solo masturbation and partnered sexual expression (Dosch et al., 2016). Conversely, a recent survey of German women found that having masturbated was associated with body acceptance (Burri & Carvalheira, 2019). In the U.S., women—and especially older women, women of size, women of color, and women living with disabling conditions—may be particularly vulnerable to poorer body image due to misogyny, sexual harassment, racism, ableism, ageism as well as the self-objectification, sexual self-monitoring, and self-embarrassment these may contribute to (Gruber & Fineran, 2016; Koch et al., 2005; Leath et al., 2020; Moin et al., 2009; Salcedo, 2022; Taskin Yilmaz et al., 2019; Thompson, 2018; Thorpe et al., 2021). Masturbation can be an important way to learn about one’s body as well as to direct joy, appreciation, and pleasure toward one’s own body, sexuality, and sense of self (Dodson, 1987; Fahs & Frank, 2014; Meiller & Hargons, 2019).

Open-ended responses related to reasons for not masturbating highlighted how erectile difficulties can interfere with men’s masturbation (not just partnered sex), as well as how masturbating may be inhibited by feeling too old or tired. Participants’ comments about erectile function highlight the importance of facilitating access to educational, therapeutic, and pharmaceutical treatments for erectile difficulties, especially given the well-established benefits of masturbation. Participants’ write-in responses also demonstrated that some people simply prefer partnered sex or feel satisfied by sex with their partner and consequently don’t choose solitary forms of sexual stimulation.

In terms of reasons participants selected for having masturbated in the prior year, the reasons most often endorsed were the same for both women and men, with no significant differences. Our findings for women were largely consistent with prior research involving convenience samples of women living in the U.S., Portugal, and Hungary. These studies have found that sexual pleasure has been the most common reason given for masturbating, with fewer women in these studies endorsing reasons such as stress relief, relaxation, or to help them fall asleep (Carvalheira & Leah, 2013; Rowland et al., 2020). However, we also found support for people masturbating due to lack of a partner and having less partnered sex than they want, offering at least some support for the compensatory model of masturbation in relation to partnered sex. Other reasons related to having levels of arousal that interfere with other activities, self-exploration, and viewing masturbation as a part of overall health and well-being.

We also found that far more men than women reported that they desired greater frequency of sex. Few participants indicated wanting less frequent sex (7% women, 1% men). However, more men wanted more frequent sex (71% men, 47% women) and more women reported being generally satisfied with their sexual frequency (45% women, 27% men). In terms of the interplay between masturbation and partnered sex, we found support for the complementary model, at least among women. That is, women’s greater frequency of partner sex was associated with greater frequency of masturbation in the prior year. Yet, we also found some support for the compensatory model of masturbation and partnered sex; both women and men who desired more frequent partnered sex were more likely to masturbate more often. These findings may also simply reflect overall levels of sexual desire. Subsequent research might examine this relationship in light of participants’ sexual desire for both partnered sex and solo masturbation, their enjoyment of each, and/or their overall sexual satisfaction.

The present study was conducted in the USA during spring 2021, a time when SARS-CoV-2 vaccines were available to adults but unevenly taken up (Levenson, 2021; Salomon et al., 2021). Although there has long been a need for greater scientific attention to masturbation, this has been particularly true during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. During this time, public health professionals have recommended that people choose masturbation over sex with people outside their household (Government of the District of Columbia, 2021; The NYC Health Department, 2021) and, globally, people have moved in and out of COVID-related stay-at-home guidance (Huang et al., 2022; Phillips et al., 2021). Masturbation and the COVID-19 pandemic may be related in other ways, other than just risk avoidance; for example, some people (due to working from home and staying at home more often) may have masturbated less often due either to lack of privacy or because they had more opportunities for partnered sex (at least if they had a household partner). Our finding that more young adult men, compared with older men, selected COVID-19 risk reduction as a reason for masturbating aligns with a recent convenience survey of Canadian college students, showing that more than half of students had used masturbation as a risk reduction strategy during the early months of the pandemic (Gilbert et al., 2021). A U.S. national study also found small but significant self-reported increases in masturbation among men during the COVID-19 pandemic (Gleason et al., 2021) whereas a U.S. nationally representative survey conducted during the initial April 2020 lockdown found that conflict between romantic/sexual behaviors was associated with decreases in several sexual behaviors, including masturbation (Luetke et al., 2020).

Strengths and Limitations

The present study used U.S. nationally representative probability sampling which enhances the ability to generalize findings to U.S. non-institutionalized adults able to read and complete surveys in the English language. The study’s survey completion rate was good especially given declining survey completion rates in recent years (Mindell et al., 2015). Where possible, we used items from prior research and from established measures. Prior studies related to reasons for and for not masturbating have often included unique items developed for their own surveys (Bowman, 2014; Carvalheira & Leah, 2013; Rowland et al., 2020), limiting the ability for direct comparisons between studies. However, the items are close enough that the general meanings hold (e.g., related to pleasure, to help fall asleep). We were also limited in our ability to make comparisons for reasons for masturbating (or not masturbating) given that prior research had been limited to college, community, or online convenience samples and the present study collected US nationally representative data from adults ages 18 and over.

Due to budget considerations and to be attentive to participant burden, we could not use as many of the items assessing reasons for, and reasons for not, masturbating as were included in the original 62- item and 72-item scales (Young & Muehlenhard, 2011). However, by including 25 of these 134 reasons we still assessed a greater number of masturbation-related reasons than most prior studies and our study findings can be generalized to U.S. adults. We selected these items by choosing both those that were more commonly addressed in prior convenience samples as well as some reasons that reflected timely issues such as privacy (e.g., due to the COVID19 pandemic and many people moving home or living with others) as well as contemporary interests in the broader sexuality field, such as related to trying to stop watching pornography or feeling unable to stop masturbating.

Further, U.S. nationally representative surveys are limited by the small proportion of participants who identify outside the gender binary, leaving the present study focused largely on people identifying as women and men. We presented descriptive data for gender nonbinary, transgender women, and transgender men participants with the hopes that these data may still be useful to the field. To be attentive to space, we did not present masturbation rates by age, sexual orientation identity, race/ethnicity, relationship type, or other demographic characteristics; in subsequent manuscripts, we hope to examine at least some of these. Finally, our sexual behavior frequency measures were limited to behaviors within the past year. While we acknowledge that sexual behavior frequencies may ebb and flow over the course of a year, we also wanted to capture an overall frequency over a longer period of time in order for a more stable estimate rather than a shorter period time which may be prone to life circumstances (e.g., illness, traveling away from partner, childbirth).

Conclusion

Our findings add to a growing body of literature on solo masturbation. Sexuality educators may find these data helpful to update sexual health curricula, especially given calls for sex-positive education that is inclusive of masturbation (van Reeuwik & Nahar, 2013). Clinicians may also find these data useful in terms of contextualizing clients’ reasons for, and for not, masturbating as well as talking through the ways that masturbation and partnered sex may be interconnected for some people. Finally, our data may serve to mark a particular moment in time during the COVID-19 pandemic that subsequent researchers can use as a benchmark to understand ongoing shifts of solo and partnered sexual activities.

Data Availability

A limited data set can be accessed by contacting the authors for data repository information.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Baćak, V., & Štulhofer, A. (2011). Masturbation among sexually active young women in Croatia: Associations with religiosity and pornography use. International Journal of Sexual Health, 23(4), 248–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2011.611220

Baumeister, R. F., Catanese, K. R., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Is there a gender difference in strength of sex drive? Theoretical views, conceptual distinctions, and a review of relevant evidence. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5(3), 242–273. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0503_5

Bowman, C. P. (2014). Women’s masturbation: Experiences of sexual empowerment in a primarily sex-positive sample. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 38(3), 363–378. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684313514855

Bullough, V. L. (2003). Masturbation: A historical overview. Journal of Psychology Human Sexuality, 14(2–3), 17–33.

Burri, A., & Carvalheira, A. (2019). Masturbatory behavior in a population sample of German women. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 16(7), 963–974.

Carvalheira, A., & Leal, I. (2013). Masturbation among women: Associated factors and sexual response in a Portuguese community sample. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 39(4), 347–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2011.628440

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. (n.d.). (2017–2019). National Survey of Family Growth Female Questionnaire. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nsfg/NSFG-2017-2019-FemaleCAPIlite-forPUF-508.pdf

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. (2022b). YRBSS questionnaires. Division of Adolescent and School Health. National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/questionnaires.htm#print

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. (2022a). NHANES 2017-March 2020 pre-pandemic questionnaire data. CDC/National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved from: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/search/datapage.aspx?Component=Questionnaire&Cycle=2017-2020

Chowdhury, M., Khan, R. H., Chowdhury, M. R. K., Nipa, N. S., Kabir, R., Moni, M. A., & Kordowicz, M. (2019). Masturbation experience: A case study of undergraduate students in Bangladesh. Journal of Population and Social Studies, 27(4), 359–372. https://doi.org/10.25133/JPSSv27n4.024

Cito, G., Micelli, E., Cocci, A., Polloni, G., Russo, G. I., Coccia, M. E., Simoncini, T., Carini, M., Minervini, A., & Natali, A. (2021). The impact of the COVID-19 quarantine on sexual life in Italy. Urology, 147, 37–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2020.06.101

Coleman, E. (2003). Masturbation as a means of achieving sexual health. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 14(2–3), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1300/J056v14n02_02

Das, A. (2007). Masturbation in the United States. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 33(4), 301–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926230701385514

Das, A., Parish, W. L., & Laumann, E. O. (2009). Masturbation in urban China. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38(1), 108–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-007-9222-z

Dekker, A., & Schmidt, G. (2003). Patterns of masturbatory behaviour: Changes between the sixties and the nineties. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality, 14(2–3), 35–48. https://doi.org/10.1300/J056v14n02_04

Dodson, B. (1987). Sex for one: The joy of selfloving. Harmony Books.

Dosch, A., Ghisletta, P., & Van der Linden, M. (2016). Body image in dyadic and solitary sexual desire: The role of encoding style and distracting thoughts. Journal of Sex Research, 53(9), 1193–1206. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2015.1096321

Elliott, J. K. (2020). Try ‘glory holes’ for safer sex during coronavirus, B.C. CDC says. Accessed on December 7, 2021 from: https://globalnews.ca/news/7204384/coronavirus-glory-holes-sex/

Fahs, B., & Frank, E. (2014). Notes from the back room: Gender, power, and (in) visibility in women’s experiences of masturbation. Journal of Sex Research, 51(3), 241–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2012.745474

Fischer, N., & Træen, B. (2022). A seemingly paradoxical relationship between masturbation frequency and sexual satisfaction. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51(6), 3151–3167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02305-8

Fischer, N., Graham, C. A., Træen, B., & Hald, G. M. (2021). Prevalence of masturbation and associated factors among older adults in four European countries. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51(3), 1385–1396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02071-z

Fu, T. C., Herbenick, D., Dodge, B. M., Beckmeyer, J. J., & Hensel, D. J. (2021). Long-acting reversible contraceptive users’ knowledge, conversations with healthcare providers, and condom use: Findings from a US nationally representative probability survey. International Journal of Sexual Health, 33(2), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2020.1870024

Gerressu, M., Mercer, C. H., Graham, C. A., Wellings, K., & Johnson, A. M. (2008). Prevalence of masturbation and associated factors in a British national probability survey. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 37(2), 266–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-006-9123-6

Gilbert, M., Chang, H. J., Ablona, A., Salway, T., Ogilvie, G., Wong, J., Campeau, L., Worthington, C., Grace, D., & Grennan, T. (2021). Partner number and use of COVID-19 risk reduction strategies during initial phases of the pandemic in British Columbia, Canada: A survey of sexual health service clients. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 112(6), 973–983. https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-021-00566-9

Gleason, N., Banik, S., Braverman, J., & Coleman, E. (2021). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on sexual behaviors: Findings from a national survey in the United States. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 18(11), 1851–1862. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.08.008

Government of the District of Columbia. (2021). Sex during the COVID-19 public health emergency. Accessed on December 7, 2021 from: https://coronavirus.dc.gov/sex

Gruber, J., & Fineran, S. (2016). Sexual harassment, bullying, and school outcomes for high school girls and boys. Violence against Women, 22(1), 112–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801215599079

Haavio-Mannila, E., Kontula, O., & Mäkinen, M. (2003) Sexual trends in the Baltic Sea area. Helsinki: Population research institute, family federation of Finland. Retrieved from: https://www.vaestoliitto.fi/uploads/2020/12/7f60ccf4-sextrendsinbalticsea00.pdf

Hald, G. M. (2006). Gender differences in pornography consumption among young heterosexual Danish adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 35(5), 577–585. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-006-9064-0

Haus, K. R., & Thompson, A. E. (2020). An examination of the sexual double standard pertaining to masturbation and the impact of assumed motives. Sexuality & Culture, 24(3), 809–834. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-019-09666-8

Herbenick, D., Reece, M., Schick, V., Sanders, S. A., Dodge, B., & Fortenberry, J. D. (2010). Sexual behavior in the United States: Results from a national probability sample of men and women ages 14–94. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7, 255–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02012.x.10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02012.x

Herbenick, D., Rosenberg, M., Golzarri-Arroyo, L., Fortenberry, J. D., & Fu, T. C. (2022). Changes in penile-vaginal intercourse frequency and sexual repertoire from 2009 to 2018: Findings from the National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51, 1103–1123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02125-2

Huang, X., Lu, J., Gao, S., Wang, S., Liu, Z., & Wei, H. (2022). Staying at home is a privilege: Evidence from fine-grained mobile phone location data in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 112(1), 286–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2021.1904819

Hungrige, A. (2016). Women's masturbation: An exploration of the influence of shame, guilt, and religiosity (Doctoral dissertation, Texas Woman's University). https://twu-ir.tdl.org/handle/11274/8755

Ivankovich, M. B., Leichliter, J. S., & Douglas, J. M., Jr. (2013). Measurement of sexual health in the US: An inventory of nationally representative surveys and surveillance systems. Public Health Reports, 128(2), 62–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549131282S1

Kaestle, C. E., & Allen, K. R. (2011). The role of masturbation in healthy sexual development: Perceptions of young adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40(5), 983–994. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-010-9722-0

Koch, P. B., Mansfield, P. K., Thurau, D., & Carey, M. (2005). “Feeling frumpy”: The relationships between body image and sexual response changes in midlife women. Journal of Sex Research, 42(3), 215–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490509552276

Laan, E., & Rellini, A. H. (2011). Can we treat anorgasmia in women? The challenge to experiencing pleasure. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 26(4), 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2011.649691

Laqueur, T. W. (2003). Solitary sex: A cultural history of masturbation. Zone Books.

Leath, S., Pittman, J. C., Grower, P., & Ward, L. M. (2020). Steeped in shame: An exploration of family sexual socialization among Black college women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 44(4), 450–467. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684320948539

Lester, P. E., Kohen, I., Stefanacci, R. G., & Feuerman, M. (2016). Sex in nursing homes: A survey of nursing home policies governing resident sexual activity. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 17(1), 71–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2015.08.013

Levenson, E. (2021). These are the states with the highest and lowest vaccination rates. CNN. Retrieved from: https://www.cnn.com/2021/05/10/us/us-vaccination-rates-states/index.html

Lindau, S. T., Dale, W., Feldmeth, G., Gavrilova, N., Langa, K. M., Makelarski, J. A., & Wroblewski, K. (2018). Sexuality and cognitive status: A U.S. nationally representative study of home-dwelling older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 66(10), 1902–1910. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15511

Luetke, M., Hensel, D., Herbenick, D., & Rosenberg, M. (2020). Romantic relationship conflict due to the COVID-19 pandemic and changes in intimate and sexual behaviors in a nationally representative sample of American adults. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 46(8), 747–762.

Meiller, C., & Hargons, C. N. (2019). “It’s happiness and relief and release”: Exploring masturbation among bisexual and queer women. Journal of Counseling Sexology & Sexual Wellness: Research, Practice, and Education, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.34296/01011009

Mindell, J. S., Giampaoli, S., Goesswald, A., Kamtsiuris, P., Mann, C., Männistö, S., Morgan, K., Shelton, N. J., Verschuren, W. M. M., & Tolonen, H. (2015). Sample selection, recruitment and participation rates in health examination surveys in Europe–experience from seven national surveys. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 15(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-015-0072-4

Moin, V., Duvdevany, I., & Mazor, D. (2009). Sexual identity, body image and life satisfaction among women with and without physical disability. Sexuality and Disability, 27(2), 83–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-009-9112-5

Oliver, M. B., & Hyde, J. S. (1993). Gender differences in sexuality: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 114(1), 29–51.

Perry, S. L. (2019). Where does masturbation fit in all this? We need to incorporate measures of solo-masturbation in models connecting sexual media use to sexual quality (or anything else) [Commentary]. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(8), 2265–2269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1379-0

Petersen, J. L., & Hyde, J. S. (2011). Gender differences in sexual attitudes and behaviors: A review of meta-analytic results and large datasets. Journal of Sex Research, 48(2–3), 149–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2011.551851

Phillips, T., Zhang, Y., & Petherick, A. (2021). A year of living distantly: Global trends in the use of stay-at-home orders over the first 12 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Interface Focus, 11(6), 20210041. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsfs.2021.0041

Primack, B. A., Shensa, A., Escobar-Viera, C. G., Barrett, E. L., Sidani, J. E., Colditz, J. B., & James, A. E. (2017). Use of multiple social media platforms and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A nationally-representative study among U.S. young adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.013

Raifman, S., Biggs, M. A., Ralph, L., Ehrenreich, K., & Grossman, D. (2021). Exploring attitudes about the legality of self-managed abortion in the US: Results from a nationally representative survey. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 19(2), 574–587. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-021-00572-z

Regnerus, M., Price, J., & Gordon, D. (2017). Masturbation and partnered sex: Substitutes or complements. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(7), 2111–2121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-0975-8

Richters, J., De Visser, R. O., Badcock, P. B., Smith, A. M., Rissel, C., Simpson, J. M., & Grulich, A. E. (2014). Masturbation, paying for sex, and other sexual activities: The second Australian Study of Health and Relationships. Sexual Health, 11(5), 461–471. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH14116

Riley, A., & Segraves, R. T. (2006). Treatment of premature ejaculation. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 60(6), 694–697. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1368-5031.2006.00818.x

Robbins, C. L., Schick, V., Reece, M., Herbenick, D., Sanders, S. A., Dodge, B., & Fortenberry, J. D. (2011). Prevalence, frequency, and associations of masturbation with partnered sexual behaviors among US adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 165(12), 1087–1093. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.142

Rodríguez, J. E., & López, A. (2016). Male masturbation device for the treatment of premature ejaculation. Asian Pacific Journal of Reproduction, 5(1), 80–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apjr.2015.12.015

Rowen, T. S., Gaither, T. W., Awad, M. A., Osterberg, E. C., Shindel, A. W., & Breyer, B. N. (2016). Pubic hair grooming prevalence and motivation among women in the United States. JAMA Dermatology, 152(10), 1106–1113. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.2154

Rowland, D. L., Kolba, T. N., McNabney, S. M., Uribe, D., & Hevesi, K. (2020). Why and how women masturbate, and the relationship to orgasmic response. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 46(4), 361–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2020.1717700

Rullo, J. E., Lorenz, T., Ziegelmann, M. J., Meihofer, L., Herbenick, D., & Faubion, S. S. (2018). Genital vibration for sexual function and enhancement: A review of evidence. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 33(3), 263–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2017.1419557

Salcedo, A. (2022). Two broadcasters body-shamed girls during a high school basketball game. They were quickly fired. Washington Post. Accessed on January 24, 2022 from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2022/01/24/maine-radio-fired-bodyshaming-girl-athletes/

Salomon, J. A., Reinhart, A., Bilinski, A., Chua, E. J., La Motte-Kerr, W., Rönn, M. M., Reitsma, M. B., Morris, K. A., LaRocca, S., Farag, T. H., Kreuter, F., Rosenfeld, R., & Tibshirani, R. J. (2021). The US COVID-19 trends and impact survey: Continuous real-time measurement of COVID-19 symptoms, risks, protective behaviors, testing, and vaccination. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(51), e2111454118. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.24.21261076

San Francisco Department of Public Health. (2021). Updated March 25, 2021. Accessed on January 24, 2022 from: https://www.sfdph.org/dph/files/ig/Tips-Safer-Sex.pdf

StataCorp. (2017). Stata statistical software: Release 15. StataCorp LLC.

Taskin Yilmaz, F., Karakoc Kumsar, A., & Demirel, G. (2019). The effect of body image on sexual quality of life in obese married women. Health Care for Women International, 40(4), 479–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2018.1542432

The NYC Health Department. (2021). Safer sex and COVID-19. Accessed on January 24, 2022 from: https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/imm/covid-sex-guidance.pdf

Thompson, L. (2018). “I can be your Tinder nightmare”: Harassment and misogyny in the online sexual marketplace. Feminism & Psychology, 28(1), 69–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353517720226

Thorpe, S., Dogan, J. N., Malone, N., Jester, J. K., Hargons, C. N., & Stevens-Watkins, D. (2021). Correlates of sexual self-consciousness among black women. Sexuality & Culture, 26(2), 707–728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-021-09916-8

van Reeuwijk, M., & Nahar, P. (2013). The importance of a positive approach to sexuality in sexual health programmes for unmarried adolescents in Bangladesh. Reproductive Health Matters, 21(41), 69–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(13)41694-4

Walsh, A. (2000). Improve and care: Responding to inappropriate masturbation in people with severe intellectual disabilities. Sexuality and Disability, 18(1), 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005473611224

Wellings, K., Palmer, M. J., Machiyama, K., & Slaymaker, E. (2019). Changes in, and factors associated with, frequency of sex in Britain: Evidence from three National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal). British Medical Journal, 365. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l1525

Young, C. D., & Muehlenhard, C. L. (2011). Attitudes toward masturbation scale. In T. D. Fisher, C. M. Davis, W. L. Yarber, & S. L. Davis (Eds.), Handbook of sexuality-related measures (3rd ed., pp 489–494). Routledge.

Younis, I., Abdel-Rahman, S. H., El-Esawi, F. M., & Al-Awady, M. A. (2018). Solo sex: Masturbation in a sample of Egyptian women. Human Andrology, 8(1), 11–18. https://doi.org/10.21608/ha.2018.1894.1017

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Lauren Broffman, Yael Cooperman, Pepper Schwartz, and Megan Zhou for their feedback on drafts of the questionnaire.

Funding

The authors are grateful to Roman Health Ventures, LLC for their funding in support of the present research (PI: Herbenick). The funders provided feedback on survey drafts but did not participate in data collection, data analysis, or drafting of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DH conceived of the study. DH, TCF, and EC wrote and/or edited the survey. TCF analyzed the data. DH, TCF, and RW wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed, revised, and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Herbenick and Dr. Coleman have served as members of the Ro Medical Advisory Board.

Ethical Approval

Study protocols and procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at Indiana University.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Herbenick, D., Fu, Tc., Wasata, R. et al. Masturbation Prevalence, Frequency, Reasons, and Associations with Partnered Sex in the Midst of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Findings from a U.S. Nationally Representative Survey. Arch Sex Behav 52, 1317–1331 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02505-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02505-2