Abstract

I consider the potential of eight text-scaling methods for the analysis of jurisprudential change. I use a small corpus of well-documented German Federal Constitutional Court opinions on European integration to compare the machine-generated scores to scholarly accounts of the case law and legal expert ratings. Naive Bayes, Word2Vec, Correspondence Analysis and Latent Semantic Analysis appear to perform well. Less convincing are the performance of Wordscores, ML Affinity and lexicon-based sentiment analysis. While both the high-dimensionality of judicial texts and the validation of computer-based jurisprudential estimates pose major methodological challenges, I conclude that automated text-scaling methods hold out great promise for legal research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In some instances, sentiment analysis only aims at establishing the direction of sentiment without consideration for its intensity, in which case it results in a binary classification (positive/negative). Even when it assumes that that topic is constant across documents, such a task only imperfectly approximates the definition of text-scaling assumed in the present paper.

To construct the wordcloud the documents were pre-processed as explained below in Sect. 4, with the exception that party arguments were kept.

First instance tribunals may process large numbers of disputing dealing with thee same topic (asylum, for example) but such courts do not usually engage in law-finding and law-creation. So their opinions tend to be of little interest from the perspective of jurisprudential change.

I also considered a combination of the vector ‘ultra-vires and souveränität, but the resulting dictionary seemed to greatly overlap with verfassungsidentität.

This is plausibly a consequence of the experts’ biases cancelling each other out.

References

Alter KJ (2001) Establishing the supremacy of European law: the making of an international rule of law in Europe. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Benoit K, Laver M (2003) Estimating Irish party policy positions using computer wordscoring: the 2002 election—a research note. Ir Polit Stud 18(1):97–107

Benoit K, Laver M, Arnold C, Pennings P, Hosli MO (2005) Measuring national delegate positions at the convention on the future of Europe using computerized word scoring. Eur Union Polit 6(3):291–313

Benzécri J-P et al (1973) L’analyse des données, vol 2. Dunod, Paris

Blei DM (2012) Probabilistic topic models. Commun ACM 55(4):77–84

Blei DM, Ng AY, Jordan MI (2003) Latent Dirichlet allocation. J Mach Learn Res 3(Jan):993–1022

Calliess C (2012) The future of the Eurozone and the role of the German Federal Constitutional Court. Yearb Eur Law 31(1):402–415

Carrubba C, Friedman B, Martin AD, Vanberg G (2012) Who controls the content of Supreme Court opinions? Am J Polit Sci 56(2):400–412

Carter DJ, Brown J, Rahmani A (2016) Reading the high court at a distance: topic modelling the legal subject matter and judicial activity of the high court of Australia, 1903–2015. UNSWLJ 39:1300

Chalkidis I, Kampas D (2019) Deep learning in law: early adaptation and legal word embeddings trained on large corpora. Artif Intell Law 27(2):171–198

Chen DL, Ash E (2019) Case vectors: spatial representations of the law using document embeddings. In: Livermore M, Rockmore D (eds) Law as data. Santa Fe Institute Press, pp 313–338

Clark TS, Lauderdale B (2010) Locating Supreme Court opinions in Doctrine space. Am J Polit Sci 54(4):871–890

Dahan S, Fuchs O, Layus M-L (2015) Whatever it takes? Regarding the OMT ruling of the German Federal Constitutional Court. J Int Econ Law 18(1):137–151

Davies B (2012) Resisting the European Court of Justice. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Deerwester S, Dumais ST, Furnas GW, Landauer TK, Harshman R (1990) Indexing by latent semantic analysis. J Am Soc Inf Sci 41(6):391–407

Epstein L, Knight J (2013) Reconsidering judicial preferences. Annu Rev Polit Sci 16(1):11–31

Evans M, McIntosh W, Lin J, Cates C (2007) Recounting the courts? Applying automated content analysis to enhance empirical legal research. J Empir Legal Stud 4(4):1007–1039

Friedman B (2006) Taking law seriously. Perspect Polit 4(02):261–276

Gibson JL, Caldeira GA, Baird VA (1998) On the legitimacy of National High Courts. Am Polit Sci Rev 92(2):343

Greenacre MJ (1984) Correspondence analysis. Academic Press, London

Grimmer J, Stewart BM (2013) Text as data: the promise and pitfalls of automatic content analysis methods for political texts. Polit Anal 21(3):267–297

Hong M (2016) Human dignity, identity review of the European arrest warrant and the Court of Justice as a listener in the dialogue of courts: Solange-III and Aranyosi: BVerfG 15 December 2015, 2 BvR 2735/14, Solange III, and ECJ (Grand Chamber) 5 April 2016, joined cases C-404/15 and C-659/15 PPU, Aranyosi and Căldăraru. Eur Const Law Rev 12(3):549–563

Kidd Q (2008) The real (lack of) difference between republicans and democrats: a computer word score analysis of party platforms, 1996–2004. Polit Sci Polit 41(03):519–525

Klemmensen R, Hobolt SB, Hansen ME (2007) Estimating policy positions using political texts: an evaluation of the wordscores approach. Electoral Stud 26(4):746–755

Klüver H (2009) Measuring interest group influence using quantitative text analysis. Eur Union Polit 10(4):535–549

Lauderdale BE, Clark TS (2014) Scaling politically meaningful dimensions using texts and votes. Am J Polit Sci 58(3):754–771

Laver M, Benoit K, Garry J (2003) Extracting policy positions from political texts using words as data. Am Polit Sci Rev 97(02):311–331

Laver M, Benoit K, Sauger N (2006) Policy competition in the 2002 French legislative and presidential elections. Eur J Polit Res 45(4):667–697

Lax JR (2011) The new judicial politics of legal doctrine. Annu Rev Polit Sci 14(1):131–157

Livermore MA, Riddell AB, Rockmore DN (2017) The Supreme Court and the judicial genre. Ariz Law Rev 59:837

Lo SL, Cambria E, Chiong R, Cornforth D (2017) Multilingual sentiment analysis: from formal to informal and scarce resource languages. Artif Intell Rev 48(4):499–527

Lowe W (2008) Understanding wordscores. Polit Anal 16(4):356–371

Lowe W (2013) There’s (basically) only one way to do it

Mahlmann M (2005) Constitutional identity and the politics of homogeneity. Ger Law J 6(2):307–317

Mayer FC (2014) Rebels without a cause: a critical analysis of the German Constitutional Court’s OMT reference. Germ Law J 15:111

Mayer FC, Walter M (2011) Die Europarechtsfreundlichkeit des BVerfG nach dem Honeywell-Beschluss. jura 33(7):532–542

Meessen KM (1994) Hedging European integration: the Maastricht Judgment of the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany. Fordham Int Law J 17:511–530

Mikolov T, Chen K, Corrado G, Dean J (2013) Efficient estimation of word representations in vector space. arXiv preprint arXiv:1301.3781

Möllers C (2011) German Federal Constitutional Court: constitutional ultra vires review of European acts only under exceptional circumstances; decision of 6 July 2010, 2 BvR 2661/06, Honeywell. Eur Const Law Rev (EuConst) 7(01):161–167

Nanda R, Siragusa G, Di Caro L, Boella G, Grossio L, Gerbaudo M, Costamagna F (2019) Unsupervised and supervised text similarity systems for automated identification of national implementing measures of European directives. Artif Intell Law 27(2):199–225

Nowag J (2016) EU law, constitutional identity, and human dignity: a toxic mix? Bundesverfassungsgericht: Mr R. Common Mark Law Rev 53(5):1441–1453

Perry PO, Benoit K (2017) Scaling text with the class affinity model. arXiv preprint arXiv:1710.08963

Petersen N (2014) Karlsuhe not only barks, but finally bites-some remarks on the OMT decision of the German Constitutional Court. Germ Law J 15:321

Pliakos A, Anagnostaras G (2017) Saving face: the German Federal Constitutional Court decides Gauweiler. Germ Law J 18:213

Proksch S-O, Slapin JB (2009) How to avoid pitfalls in statistical analysis of political texts: the case of Germany. Germ Polit 18(3):323–344

Proksch S-O, Slapin JB (2010) Position taking in European Parliament speeches. Br J Polit Sci 40(03):587–611

Proksch S-O, Slapin JB, Thies MF (2011) Party system dynamics in post-war Japan: A quantitative content analysis of electoral pledges. Electoral Stud 30(1):114–124

Remus R, Quasthoff U, Heyer G (2010) SentiWS—a publicly available German-language resource for sentiment analysis. In: LREC

Rheault L, Cochrane C (2020) Word embeddings for the analysis of ideological placement in parliamentary corpora. Polit Anal 28(1):112–133

Schmid CU (2001) All bark no bite: notes on the Federal Constitutional Court’s “Banana Decision”. Eur Law J 7:95

Schmidt SK (2013) Sense of Deja Vu: the FCC’s preliminary European stability mechanism verdict. Germ Law J 14:1

Shapiro MM (1968) The Supreme Court and administrative agencies. Free Press, New York

Slapin JB, Proksch S-O (2008) A scaling model for estimating time-series party positions from texts. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 52(3):705–722

Stein T (2011) Always steering a straight course? The German Federal Constitutional Court and European Integration. ERA Forum 12(1):219–228

Sweet AS (2004) The judicial construction of Europe. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Thym D (2009) In the name of Sovereign statehood: a critical introduction to the Lisbon judgment of the German Constitutional Court. Common Mark Law Rev 46(6):1795–1822

Tomuschat C (2010) Lisbon: terminal of the European integration process?: The Judgment of the German Constitutional Court of 30 June 2009. Zeitschrift für ausländisches öfentliches Recht und Völkerrecht 70(2):251–282

Weiler J (1995) Does Europe need a constitution? Demos, Telos and the German Maastricht Decision. Eur Law J 1(3):219–258

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledge financial support from European Research Council Horizon 2020 Starting Grant #638154 (EUTHORITY).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Interpreting unsupervised models

Surely, one can use the word parameter estimates of a Wordfish model to interpret and validate the dimension being scaled. Figure 9 depicts the \(\psi\) and \(\beta\) values of all words appearing in the corpus. Words with high \(\psi\) value, like “Europa”, are words that appear in similar proportion across documents. Words with non-zero \(\beta\) value are those that effectively discriminate among the documents (here negative values can be interpreted as associated with Euroscepticism and positive values with integration-friendliness). I highlighted some terms, which can be related to the frames emerging from Figs. 3 and 8. However, even if the results feel right–as they would seem here–it could that the second largest or third largest dimension is, in fact, the relevant one. But the researcher will not know unless she scales these dimensions too. Something Wordfish does not allow.

As explained in Sect. 3, the dimensions generated by an unsupervised model can be explored and interpreted by inspecting the words associated with these dimensions. Figure 12 shows how words likeee “Volk”, “Souveränität”, “Nationalstaat” (nation state), “Demokratie”, “Ultraviresakt” (ultra vires action), “Vorlagepflicht” (duty to request a preliminary reference) and even “Griechenland” (Greece) to see how they relate to dimension 2 from CA. Here two distinct frames emerge from the analysis, namely an integration-friendly frame associated with positive values on the y-axis and a Eurosceptic, state-centred frame associated with negative values on the y-axis. This, again, is consistent with what scholars say about the German Constitutional Court’s rhetoric (Thym 2009; Stein 2011; Weiler 1995; Calliess 2012; Tomuschat 2010; Möllers 2011).

Figure 13 depicts the \(\psi\) and \(\beta\) values of the Wordfish model for all words appearing in the corpus. Words with high \(\psi\) value, like “Europa”, are words that appear in similar proportion across documents. Words with non-zero \(\beta\) value are those that effectively discriminate among the documents. Here negative values can be interpreted as associated with Euroscepticism and positive values with integration-friendliness. The plot—notably the words “terrorismus” and datei”—suggests that Wordfish collapses the first and second dimension of CA into a single dimension.

1.2 Word embeddings

See Table 2

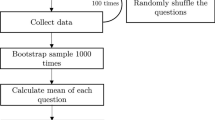

1.3 Validation

See Fig. 14.

Correlation of computer-generated estimates in pairwise comparisons with mean value of expert ratings (\(N=153\)). Plot shows mean estimate of Spearman correlation with 95% confidence interval. Results for supervised methods exclude the two training opinions, Solange I and Solange II. Except for Wordscores, ML Affinity and Dictionary, all models are significant at \(p<0.01\)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dyevre, A. The promise and pitfall of automated text-scaling techniques for the analysis of jurisprudential change. Artif Intell Law 29, 239–269 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10506-020-09274-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10506-020-09274-0