Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has necessitated adaptations in how healthcare services are rendered. However, it is unclear how these adaptations have impacted HIV healthcare services across the United States. We conducted a systematic review to assess the impacts of the pandemic on service engagement, treatment adherence, and viral suppression. We identified 26 total studies spanning the beginning of the pandemic (March 11, 2020) up until November 5, 2021. Studies were conducted at the national, state, and city levels and included representation from all four CDC HIV surveillance regions. Studies revealed varying impacts of the pandemic on HIV healthcare retention/engagement, medication adherence, and viral suppression rates, including decreases in HIV healthcare visits, provider cancellations, and inability to get prescription refills. Telehealth was critical to ensuring continued access to care and contributed to improved retention and engagement in some studies. Disparities existed in who had access to the resources needed for telehealth, as well as among populations living with HIV whose care was impacted by the pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There are over 1.2 million people living with human immunodeficiency virus (PWH) in the United States (U.S.) [1]. Current treatment recommendations for PWH include initiation of care for those newly diagnosed, regular attendance of appointments with HIV providers, and antiretroviral therapy (ART) access and adherence [2]. These services are critical to reaching and maintaining viral suppression, which prevents HIV-associated morbidity and mortality and prevents further disease transmission [3]. Unfortunately, the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has led to widespread disruptions in the U.S. healthcare system and cancellation or postponement of preventive and routine healthcare appointments, including those that provide critical services to PWH [4]. These disruptions, coupled with pre-existing health inequities experienced by PWH including lack of transportation, limited access to technology, and poverty [5], could have a lasting impact on individual and community health. One modeling study predicted that disruptions in HIV-related services during the pandemic, including ART initiation and viral suppression, could lead to an additional 4.8 deaths in a population of 2000 HIV-infected men who have sex with men over a year in Baltimore, Maryland [6].

People with HIV are at high risk for pandemic-related disruptions because they require consistent and regular engagement with the healthcare system to maintain viral suppression [5]. There is also greater representation of people with socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds, as well as over representation of minority communities, which may also influence health seeking behavior and engagement in care during the pandemic [7]. Barriers such as lack of access to the technology required for telemedicine and inability to travel to receive health services may disproportionately impact these individuals [5]. Additionally, PWH often suffer from other comorbidities that may increase their risk for COVID-19-related morbidity and mortality, and thus may be more fearful to attend in-person appointments, including laboratory appointments necessary to monitor their health [8].

The COVID-19 pandemic has necessitated several adaptations in how HIV services are rendered, such as massive upscaling of telemedicine, increased outreach by social workers, and increased use of mail-order pharmacies [9]. It remains to be seen how the transition of healthcare services during the pandemic has impacted access to and use of HIV healthcare services across the U.S. The objective of this systematic review is to synthesize existing literature to better our understanding of how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted engagement and retention in HIV healthcare services, treatment adherence including ART access and utilization, as well as viral suppression for PWH in the U.S. Additionally, it aims to identify some of the unique and innovative strategies implemented during the pandemic to adapt HIV care models and maintain these critical services.

METHODS

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Supplementary Table 1) [10]. This review and protocol have been registered on PROSPERO (CRD42021249550).

Data sources

Electronic databases searched for this review were PubMed, Embase, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Web of Science, and PsycINFO. PubMed and Embase were used as they provide extensive access to the biomedical literature. CINAHL, Web of Science, and PsycINFO provided additional access to the nursing and allied health literature, behavioral and social science literature, and literature from other disciplines such as arts and humanities.

The search used a combination of PubMed Medical Subject Heading terms, including variations of ‘COVID-19’ and ‘HIV’ that were developed in consultation with a medical librarian and later adapted for CINAHL, Embase, Web of Science, and PsycINFO (Supplementary Table 2). The COVID-19 search string was modified from The Johns Hopkins University Welch Medical Library [11]. Additional search terms (e.g., “United States”) were added to narrow the focus of the review to the U.S. Searches of relevant organizational websites (e.g., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health) and of the grey literature (e.g., Google, Google Scholar) were also conducted to locate resources not identified in the database search. An initial search using the PubMed, CINAHL, and Embase databases was conducted on September 9, 2021. The same search was re-run prior to data analysis on November 5, 2021 to identify any newly published articles. The PsycINFO and Web of Science databases were later added (using a date cutoff of November 5, 2021) to capture any additional literature not identified in the previous databases.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Included studies were published in English-language journals and discussed impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on retention and engagement in HIV healthcare services (e.g., changes in the number of clinic visits, non-attendance rates, etc.), treatment access and utilization (e.g., ART prescription refills, ability to obtain ART, treatment adherence, etc.), and viral suppression rates specific to PWH.

Exclusion criteria included articles that focused solely on healthcare access during the pandemic for PWH to treat conditions other than HIV (e.g., for hypertension, substance use, mental health disorders, etc.) or that only discussed HIV prevention (e.g., PrEP, condom use) or testing during the COVID-19 pandemic. “Calls to action”, notes from the field, or other types of commentaries or letters that provided anecdotal recommendations or data, such as discussion of changes made to HIV care models, but that did not either collect data from providers or patients or discuss the study methodology used were also excluded. Finally, the scope of this review was limited to only those studies published in the U.S. to allow for a more thorough and targeted understanding of the impacts of the pandemic on different regions of the US.

Study selection

Article titles and abstracts were divided up amongst research team members (DM, OO, BD, or SES) and screened independently for eligibility by two reviewers using the previously stated inclusion criteria. Articles included after title and abstract review were then reviewed at-length independently by two reviewers for study inclusion. Any discrepancies that arose between the two reviewers during title and abstract screening or full article review were discussed until consensus was reached. References of the included articles were also screened for relevance. Article screening and review was completed using the web-based software Covidence [12].

Data extraction

Data was independently extracted by four reviewers, in pairs of two (DM, OO, BD, or SES) using a survey created in Google Forms previously piloted by the research team. Any discrepancies that arose between the reviewers during data extraction were discussed until consensus was reached. Extracted data included study design; study outcome(s); study location; sample description; observable measures; time period of study data collection; data on retention or engagement in HIV healthcare services, medication adherence, and viral suppression; and adaptations in HIV healthcare delivery models made to overcome challenges introduced by the COVID-19 pandemic. After abstraction, studies were organized by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Prevention HIV surveillance regions and by study sample characteristics (e.g., economically disadvantaged, older adults, etc.) to facilitate comparisons of COVID-19 impacts.

Quality of evidence assessment

The quality of evidence included in this review was assessed independently by two study researchers (DM, OO, BD, or SES) using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [13]. This tool is designed to be used for systematic literature reviews that include studies with qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches [13]. Studies are assessed across five different criteria depending on the study type. These criteria include [13]:

-

Qualitative studies: adequacy of research approach used, adequacy of data collection, appropriate derivation of data, appropriate interpretation of data, coherence of data across sources.

-

Quantitative (randomized controlled trials) studies: appropriate randomization, comparability of groups at baseline, completeness of outcome data, blinding, adherence of participants to intervention.

-

Quantitative (non-randomized) studies: representativeness of the sample to target population, use of appropriate measurements, completeness of outcome data, accountment of confounders, intervention administered as intended.

-

Quantitative descriptive studies: relevance of sampling strategy, representativeness of the sample to target population, use of appropriate measurements, low risk for nonresponse bias, use of appropriate statistical analysis.

-

Mixed methods studies: adequate rationale for study design, appropriate integration of study components, appropriate interpretation of data, adequacy in addressing divergencies in study data, adherence to quality criteria for each method used.

Any discrepancies that arose between the two reviewers during the quality assessment process were discussed until consensus was reached.

Statistical analysis

Due to the heterogeneity of study data reported in this systematic review, a meta-analysis was not conducted. The results are instead presented according to thematic areas present across studies.

RESULTS

Study selection

In total, the five database searches yielded 908 articles. After de-duplication, a total of 607 article titles and abstracts were screened. Five hundred and twenty-three studies were excluded during title and abstract screening, and 84 underwent full text review. Two additional articles and one report were later screened that were identified through the search of organizational websites and grey literature and review of included article citations. In total, 26 articles were included in the review (Fig. 1).

PRISMA flow diagram

From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Methodological quality of the included studies

Quality of evidence was assessed using the MMAT. The one qualitative study identified in this review met all five methodological quality criteria (Table 1). Of the twenty quantitative descriptive studies (Table 2), most used a relevant sampling strategy for the research question (95%), appropriate measurements (90%), and appropriate statistical analyses based on the research question (90%). Nearly three-quarters (70%) used a sample representative of the target population and 40% had a low risk for nonresponse bias. Of the five mixed methods studies (Table 3), all (100%) had rationale for using a mixed methods design and integrated and interpreted the different study components adequately. Over half (60%) of the studies addressed inconsistencies in the data and adhered to the criteria necessary for the methods utilized.

Studies characteristics

Descriptions of the study type, sample, sample size, and study location can be found in Tables 1-3 and Supplementary Table 3. Most articles (n = 20) were quantitative, non-experimental, descriptive studies and included cross-sectional and longitudinal surveys, a time series analysis, and retrospective reviews of electronic health records or other data sources. The articles also included mixed methods studies (n = 5) and one qualitative study. Studies were conducted at the city and state levels and included all four U.S. CDC National HIV Surveillance System regions. 38% of studies were conducted in the southern region of the U.S., which is also disproportionately impacted by HIV [14]. Five studies used data collected from a nationally representative sample.

Included studies primarily used convenience sampling and recruited participants from various sources. Several studies used survey responses or other data (e.g., from electronic health records, interviews) from participants who were previously or currently enrolled in clinical trials or other study cohorts or interventions (n = 12) [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26] or who were existing HIV clinic patients (n = 7) [27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. Three studies recruited participants using social media [34,35,36], one study used participants who completed an separate online survey that linked to a COVID-19 survey [37], and one study recruited participants using mailing lists [38]. Two studies utilized data provided by Ryan White clinics [9, 39].

Fifteen studies looked at the impacts of the pandemic within specific communities living with HIV, including those who identified as Black or LatinX [16, 18], identified as a member of the LGBTQ community or MSM [23, 34, 37], identified as Black MSM [26, 35], were of older age [19, 38], were economically disadvantaged [22, 24, 28], or those who reported substance use [21, 25, 30]. Of the other nine studies that reported participant data (e.g., excluding the two studies that used data provided by Ryan White clinics), seven included varying levels of representation across genders, sexual orientations, races, ethnicities, and other demographic factors [15, 17, 20, 29, 31, 32, 36]. Two did not provide a demographic overview of the study sample [27, 33].

Themes included impacts on retention and engagement in HIV healthcare services, challenges in filling or obtaining ART prescriptions, and changes in viral suppression rates. Table 4 provides a summary of the relevant findings of each article, organized by study sample characteristics. Supplementary Table 3 provides a more thorough database of specific findings and statistical tests, as they relate to the research questions of this systematic review.

Retention and engagement in HIV healthcare services

Studies revealed decreased and missed HIV healthcare visits [18, 22, 25, 29, 35, 37, 38], cancellation of visits by healthcare providers [18, 22, 25, 35], changes in and difficulty accessing medical care [17, 21, 34], decreased confidence or ability to manage HIV care [30, 36], and an inability to access other support services such as social workers [18, 36]. These findings primarily came from participant-reported cross-sectional data and included studies conducted at the national level and from all four geographic regions. The percentage of studies reporting decreased or missed HIV healthcare visits or changes in PWH’s ability to attend visits ranged from 6% [22] to as high as 46% [38]. In the southern region, six of the seven studies that included quantitative data on HIV healthcare visits and challenges with care reported less than 20% of study participants had missed a scheduled HIV healthcare visit, did not complete a visit, or had challenges getting care [19,20,21,22, 25, 31]. Two studies conducted in the midwest region had similar findings, with 13.5% of participants in one study reporting changes or loss in medical care [17] and 21% of scheduled HIV clinic visits in another study missed by patients [29]. Three studies in total—one each from the western, northeastern, and southern regions—reported missed or cancelled visits in approximately 45% of study participants [18, 35, 38]. Two of these studies were conducted in minority populations [18, 35].

Participants in three studies—two from the southern region and one from the northeastern region—reported having visits cancelled by their healthcare provider, ranging from 45% [25] to nearly 70% of respondents [18]. Several studies also captured PWH who themselves had cancelled or avoided healthcare due to the COVID-19 pandemic, including due to fear of contracting SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19 disease [16, 18, 35]. The percentage of respondents who reported cancelling/avoiding medical care due to the pandemic ranged from 18% [16] to 45% [35].

Two studies from the western region found no changes in HIV healthcare visits when comparing time periods during the pandemic to time periods previous to the pandemic [24, 28]. For example, Hickey et al. (2021) found no significant difference when comparing the mean number of visits per month. Additionally, one retrospective review of patient data from the southern region found a statistically significant increase in visit completion during the pandemic (either in-person or telehealth) [20]. This included an increase in the percentage of women and Black patients who completed visits, which was attributed in part to the increase in telehealth [20]. Ryan White providers reported anecdotal reductions in “no show” appointments and improved access to “hard to reach populations,” which many attributed to the increased use and availability of telehealth [9].

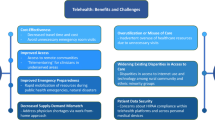

Telehealth, along with the use of other technologies, helped to ensure continued access to HIV services during the pandemic. There were increases in the number of clinics that offered telemedicine services and the percentage of appointments conducted via telemedicine, when comparing time periods before the pandemic to those during the pandemic [9, 15, 20, 27]. For example, one San Francisco HIV clinic conducted 86.9% of all appointments by telehealth from March to June 2020, compared to 5.3% from October 2019 to March 2020 [27]. Another technology that helped increase engagement during the pandemic included a mobile health intervention known as PositiveLinks that allowed sharing of messages between HIV providers and their patients [33].

Several studies that compared the impacts of COVID-19 within certain populations identified disparities in access to and engagement with healthcare services. Three studies found differences in the ability to engage with or access healthcare providers when comparing individuals with vs. without HIV [17, 34, 35], including in a population of Black/African American MSM [35] and amongst men who identified as LGBTQ [34]. For example, McKay et al., in a national study of members of the LGBTQ community, found that HIV positive men were 55% more likely to report challenges in accessing healthcare compared to HIV negative men [34]. Another study found disparities when comparing Black and LatinX patients to White patients, whom they found had a lower odds of completing video telehealth visits (vs. phone only) [31]. This study also found lower odds of completing video visits amongst older adults (compared to younger) and those on public insurance (compared to private)[31]. Another study found that ability to attend appointments via telephone, rather than in-person, improved the odds of visit completion amongst PWH who attended a safety-net clinic in California [28].

Disparities in which providers were impacted by COVID-19 related disruptions were also noted. Qiao et al. (2021) found evidence that less HIV service interruptions may have occurred in geographic areas with a higher percentage of insured individuals. Importantly, existing community-based interventions to improve HIV care engagement helped to ensure continuity of care during the pandemic, including for vulnerable communities such as those experiencing unstable housing [24, 28, 33].

Patient and provider perspectives on and challenges around the use of telehealth varied. Patient-reported advantages of telemedicine included that it was convenient [18, 27] and was safer as it reduced opportunity for SARS-CoV-2 transmission [27]. Disadvantages included lack of access to technology and technical challenges [18, 23, 27], unfamiliarity with using video platforms [27], and lack of human connection with the HIV service provider [18, 27]. Barriers around the use of telemedicine from the provider perspective included lack of patient access to technology [9, 29], challenges with reimbursement [9], and lack of clarity around telemedicine documentation and on which patients met criteria for the use of telemedicine [29]. Workarounds to these barriers included the designation of “telehealth champions”, the use of templates to guide workflows, and the use of telephone visits instead of video [29], as well as providing patients’ access to phone cards or data plans [9].

Challenges in filling or obtaining ART prescriptions

Studies also identified participants who reported having difficulties filling or obtaining their ART prescriptions and included a national study as well as studies from the southern, northeastern, midwestern, and western regions [16, 18, 22, 25, 26, 37]. These percentages ranged from between approximately 6–22% of respondents living with HIV [16, 18, 22, 25, 26, 37]. The largest percentage of individuals who reported difficulties in accessing ART was found in a sample of Black MSM and transgender women living in Chicago [26]. Studies also captured participant-reported missed ART doses [18, 22, 23, 30, 38]. For example, one study of PWH who reported alcohol/drug use found that 12% missed 2 or more ART doses during the week, compared to 5% before the pandemic [30]. The largest percentage of participants who reported missing ART doses was found in a cross-sectional survey of older adults (> 50 years of age) living with HIV, where 24% reported missing a dose [38]. Some of the reported reasons for missing ART doses in the literature included forgetting to take doses [38], disruptions in regular routines [23], and inability to get a prescription or get to a pharmacy [18, 25, 37]. Studies that assessed ART adherence or coverage identified only small decreases when comparing time periods during the pandemic to before the pandemic [15, 18, 37]. One study reported increased adherence to ART due to heightened fears of participant’s increased risk of COVID-19-related morbidity and mortality as a PWH [18].

Disparities were also noted in those who experienced interruptions in their ART regimen, and were particularly pronounced in individuals who experienced greater COVID-19 related impacts on their ability to work or travel [16, 26], were unable to attend healthcare appointments [38], or practiced stricter COVID-19 protective measures [25]. For example, Bogart et al. (2021) found that HIV patients who had experienced COVID-19 related disruptions to their employment, ability to pay rent, and ability to use public transportation had a 41% reduction in their odds of ART adherence. Kalichman et al. (2020) found that those who followed stricter COVID-19 protective measures reported more difficulty in getting their medications. One study also found that those who had been exposed to greater interpersonal violence also reported greater difficulties in obtaining their ART medications [26].

Providers took several measures to improve ART adherence during the pandemic. Some of these measures included extended or multi-month refills, mail-order pharmacy, and assistance with prescription pick-up [9, 29, 39], reaching out to patients on how to refill medications during COVID-19-related lockdowns [21], and regular adherence assessments by pharmacists [32].

Changes in viral suppression rates

Very few studies reported data on changes in viral suppression rates, when comparing time periods during the pandemic to periods before the pandemic. For the four studies that did, three found no significant difference in either the odds of viral suppression [24] or the proportion with viral suppression [15, 32]. Importantly, one of these studies was conducted on unhoused individuals who had access to a “low-barrier, high intensity HIV primary care program”, which likely mitigated the impact of the pandemic in this population [24]. However, while the percentage of those virally suppressed in this population did not change significantly during the pandemic (47%) vs. pre-pandemic (48%), rates were inadequate in both time periods [24]. Only one study found an increase in the odds of viral non-suppression when comparing the time periods [28]. This study also found higher odds of viral non-suppression in those experiencing homelessness during the pandemic compared to before the pandemic [28]. One study that compared viral suppression rates for those who attended visits via telephone vs. in-person during the pandemic found higher rates in those who could attend via telehealth [29].

DISCUSSION

This systematic review highlights how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted retention and engagement in HIV services, ART adherence, and viral suppression rates for PWH in the U.S. Articles were identified from all four CDC HIV Surveillance System regions and indicate varying impacts of the pandemic within and across these regions. In the southern region, which has some of the highest rates of HIV diagnoses per 100,000 people [14], four of the studies identified in this review found minimal to no negative impacts on retention or engagement in healthcare services and medication adherence, and included studies conducted within older PWH [19], people who inject drugs [21], underserved populations [22], and an existing HIV cohort [20]. However, two studies found larger impacts on ability to attend HIV care appointments, including in Black MSM [35] and in people who were actively using substances [25]. Studies from the western, northeast, and midwest regions found some impacts within these areas, but again these differed by the city/state, how the participants were recruited, and how impacts within these areas were measured. Importantly, eleven studies identified disparities, such as by HIV status, race/ethnicity, age, income, housing status, and access to video telehealth, in those that were most impacted by COVID-19 related interruptions, and these disparities were found in studies from all but the northeastern region.

This review identified only four articles that compare pre-pandemic viral suppression rates to time periods during the pandemic. This may be due to the fact that impacts on viral suppression rates may take more time to appear clinically and be reported in the literature than the timeframe covered by this systematic review. While three of the studies that did look at changes in viral suppression rates found no significant changes [15, 24, 32], one did find a significant increase in the odds of viral nonsuppression after the initiation of shelter-in-place orders within PWH who utilize a safety-net clinic [28]. Data on changes in viral suppression rates, in addition to participant-reported incidences of missed or cancelled visits and challenges accessing ART, will be important to fully understanding the impacts of the pandemic on the long-term health of PWH. Additionally, data on HIV transmission rates will provide evidence as to whether pandemic-related changes in viral suppression rates led to increased disease transmission. This review also identified only two studies that addressed changes in visit frequency [24, 29], likely because most studies were conducted in the first year of the pandemic. Additional research looking at changes in the chronicity and frequency of visits during the duration of the pandemic will also be critical to fully understanding its impacts.

As the U.S. continues to experience waves of COVID-19 outbreaks, it will be critical that HIV providers, health systems, and policy makers understand the additional burdens that the pandemic puts on PWH. For example, syndemic health problems in PWH, such as substance use, mental health disorders, and malnutrition, coupled with the additional challenges introduced by the pandemic, put them at increased risk for adverse outcomes related to the pandemic [40]. Additionally, several studies in this review found that specific communities, including those experiencing homelessness [28], with substance use disorders [25, 30], who are of minority race/ethnicity [16, 18], MSM [23, 37], or who use public insurance or lost health insurance [26, 31], have suffered interruptions in HIV services during the pandemic. This is particularly concerning as those who experience social inequality, stigma, racism, and discrimination have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic, and interruptions in HIV treatment may make them more susceptible to COVID-19 related morbidity and mortality [41].

Several adaptations in care models for PWH, including telemedicine, messaging applications, and mail order pharmacy, were highlighted in this review and have been critical interventions to ensure continuity of care during the pandemic. This is supported by several studies in this review which highlighted minimal impacts on retention/engagement in care and medication adherence. However, there are severe disparities in which communities have access to the resources needed to utilize telemedicine. For example, one study found that 41% of Medicare beneficiaries lacked access to a computer, 40.9% lacked access to a smartphone with a wireless data plan, and access was lower in Black and Hispanic populations, the elderly, and those on Medicaid [42]. Additionally, lack of human connection, lack of knowledge on how to use telemedicine, and increased risk for disclosure of personal information similarly indicate that telemedicine is not a panacea to replace in-person visits. It is critical that HIV service providers implement diverse and flexible strategies that are cognizant of the resources available to and comfort of their patients and that help ensure access to services as the country continues to confront the COVID-19 crisis. This will be particularly important due to the protracted nature of this pandemic, with ebbs and flows in hospitalization rates (and subsequent triggering of changes in clinic operating status) and in the economic impacts on communities which may limit access to or use of care. Furthermore, health systems must learn from their experiences providing care to these populations during this health emergency and incorporate them into preparedness plans to help ensure continued access to services during future public health emergencies.

This review is subject to several limitations. First, there remains the possibility that we omitted important and relevant articles. Second, the studies identified in this review relied primarily on patient reported interruptions in HIV services rather than clinical (e.g., viral suppression rates) or other data sources (e.g., clinic visit numbers). This increases the risk for bias (specifically, selection and recall bias) and decreases the generalizability of the data. Eleven studies also used data from patients previously or currently enrolled in studies or interventions, and these individuals may be systematically different than those who are not currently enrolled in a study. Additionally, the care received through these studies or interventions may not be representative of the standard or care experienced by other PWH across the U.S. Third, due to the protracted nature of the pandemic and the changing case numbers and subsequent impact on health systems, patient responses may have been only applicable to certain time periods within the pandemic. For example, this review was conducted prior to the emergence of the Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variant, which caused significant impacts on healthcare systems across the U.S. Differences in state responses (such as stay-at-home orders), as well as adaptations in service delivery by HIV clinics made early in the pandemic, may have also influenced which regions and populations were impacted. Finally, this review only included studies conducted in the U.S., and thus the results may not be generalizable to other countries.

However, there are several strengths of this study as well. First, the review adhered to rigorous PRISMA standards and was aided by an information specialist. Second, to our knowledge, this is the first systematic review that synthesizes data on pandemic-related impacts on HIV healthcare services in the U.S. We believe that this review provides an important snapshot of the impacts of the pandemic thus far on PWH, the challenges they have faced, and the changes providers have made to help ensure continued access to services.

Conclusions

This review suggests that COVID-19 has had varying impacts on HIV healthcare service delivery within and across CDC regions, and innovations in care delivery have been critical. Evidence also indicates that these innovations may improve access to and use of these services and should be maintained post-pandemic. Importantly, disparities were found to exist within certain communities in the magnitude of the impacts of the pandemic on HIV healthcare services that could lead to increased morbidity and mortality. It is critical that HIV service providers and health systems understand barriers faced by these communities and implement policy and practice changes that help ensure improved and continued access to care. Additional research will also be critical to better understand the impacts of interruptions in care on viral suppression rates. Disease surveillance will also help identify any impacts on HIV transmission rates. Finally, integrating these lessons learned into emergency preparedness plans will help reduce the impacts of future public health emergencies on the availability of services for PWH.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its supporting files.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Kaiser Family Foundation. The HIV/AIDS Epidemic in the United States: The Basics. KFF 2021. https://www.kff.org/hivaids/fact-sheet/the-hivaids-epidemic-in-the-united-states-the-basics/ (accessed October 7, 2021).

National Institutes of Health. Adherence to the Continuum of Care | NIH 2017. https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/adult-and-adolescent-arv/adherence-continuum-care (accessed October 7, 2021).

National Institute of Health. Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy | NIH 2019. https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/adult-and-adolescent-arv/initiation-antiretroviral-therapy (accessed October 7, 2021).

Ridgway JP, Schmitt J, Friedman E, Taylor M, Devlin S, McNulty M, et al. HIV Care Continuum and COVID-19 Outcomes Among People Living with HIV During the COVID-19 Pandemic, Chicago, IL. AIDS Behav 2020:1–3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02905-2.

Waterfield KC, Shah GH, Etheredge GD, Ikhile O. Consequences of COVID-19 crisis for persons with HIV: the impact of social determinants of health. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:299. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10296-9.

Mitchell KM, Dimitrov D, Silhol R, Geidelberg L, Moore M, Liu A, et al. The potential effect of COVID-19-related disruptions on HIV incidence and HIV-related mortality among men who have sex with men in the USA: a modelling study. Lancet HIV. 2021;8:e206–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(21)00022-9.

Chenneville T, Gabbidon K, Hanson P, Holyfield C. The Impact of COVID-19 on HIV Treatment and Research: A Call to Action. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:4548. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124548.

Prabhu S, Poongulali S, Kumarasamy N. Impact of COVID-19 on people living with HIV: A review. J Virus Erad. 2020;6:100019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jve.2020.100019.

Dawson L, Kates. Delivering HIV Care and Prevention in the COVID Era: A National Survey of Ryan White Providers - Issue Brief. KFF 2020. https://www.kff.org/report-section/delivering-hiv-care-prevention-in-the-covid-era-a-national-survey-of-ryan-white-providers-issue-brief/ (accessed October 8, 2021).

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

Lobner K. Welch Medical Library Guides: COVID-19 Resources: Research Resources 2021. https://browse.welch.jhmi.edu/covid-19/databases (accessed February 16, 2021).

Covidence - Better systematic review management. Covidence 2021. https://www.covidence.org/ (accessed February 16, 2021).

Hong QN, Gonzalez-Reyes A, Pluye P. Improving the usefulness of a tool for appraising the quality of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). J Eval Clin Pract. 2018;24:459–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12884.

CDC. HIV in the United States by Region. Cent Dis Control Prev 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/overview/geographicdistribution.html (accessed January 30, 2022).

McGinnis KA, Skanderson M, Justice AC, Akgün KM, Tate JP, King JT, et al. HIV care using differentiated service delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide cohort study in the US Department of Veterans Affairs. J Int AIDS Soc. 2021;24(Suppl 6):e25810. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25810.

Bogart LM, Ojikutu BO, Tyagi K, Klein DJ, Mutchler MG, Dong L, et al. COVID-19 Related Medical Mistrust, Health Impacts, and Potential Vaccine Hesitancy Among Black Americans Living With HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2021;86:200–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000002570.

Cooley SA, Nelson B, Doyle J, Rosenow A, Ances BM. Collateral damage: Impact of SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in people living with HIV. J Neurovirol. 2021;27:168–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13365-020-00928-y.

Gwadz M, Campos S, Freeman R, Cleland CM, Wilton L, Sherpa D, et al. Black and Latino Persons Living with HIV Evidence Risk and Resilience in the Context of COVID-19: A Mixed-Methods Study of the Early Phase of the Pandemic. AIDS Behav. 2021;25:1340–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03177-0.

Algarin AB, Varas-Rodríguez E, Valdivia C, Fennie KP, Larkey L, Hu N, et al. Symptoms, Stress, and HIV-related care among older people living with HIV during the COVID-19 pandemic, Miami, Florida. AIDS Behav. 2020;24:2236–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02869-3.

El-Nahal WG, Shen NM, Keruly JC, Jones JL, Fojo AT, Lau B, et al. Telemedicine and visit completion among people with HIV during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to pre-pandemic. AIDS Lond Engl. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000003119.

Genberg BL, Astemborski J, Piggott DA, Woodson-Adu T, Kirk GD, Mehta SH. The health and social consequences during the initial period of the COVID-19 pandemic among current and former people who inject drugs: A rapid phone survey in Baltimore, Maryland. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;221:108584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108584.

Tamargo JA, Martin HR, Diaz-Martinez J, Trepka MJ, Delgado-Enciso I, Johnson A, et al. COVID-19 Testing and the Impact of the Pandemic on the Miami Adult Studies on HIV Cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2021;87:1016–23. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000002680.

Rhodes SD, Mann-Jackson L, Alonzo J, Garcia M, Tanner AE, Smart BD, et al. A Rapid Qualitative Assessment of the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on a Racially/Ethnically Diverse Sample of Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men who Have Sex with Men Living with HIV in the US South. AIDS Behav. 2021;25:58–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03014-w.

Hickey MD, Imbert E, Glidden DV, Del Rosario JB, Chong M, Clemenzi-Allen A, et al. Viral suppression during COVID-19 among people with HIV experiencing homelessness in a low-barrier clinic-based program. AIDS Lond Engl. 2021;35:517–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000002793.

Kalichman SC, Eaton LA, Berman M, Kalichman MO, Katner H, Sam SS, et al. Intersecting Pandemics: Impact of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) Protective Behaviors on People Living With HIV, Atlanta, Georgia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2020;85:66–72. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000002414.

Chen Y-T, Duncan DT, Del Vecchio N, Timmins L, Pagkas-Bather J, Lacap S, et al. COVID-19-Related Stressors, Sex Behaviors, and HIV Status Neutral Care Among Black Men Who Have Sex With Men and Transgender Women in Chicago, USA. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2021;88:261–71. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000002770.

Auchus IC, Jaradeh K, Tang A, Marzan J, Boslett B. Transitioning to Telehealth During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Patient Perspectives and Attendance at an HIV Clinic in San Francisco. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2021;35:249–54. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2021.0075.

Spinelli MA, Hickey MD, Glidden DV, Nguyen JQ, Oskarsson JJ, Havlir D, et al. Viral suppression rates in a safety-net HIV clinic in San Francisco destabilized during COVID-19. AIDS Lond Engl. 2020;34:2328–31. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000002677.

Fadul N, Regan N, Kaddoura L, Swindells S. A Midwestern Academic HIV Clinic Operation during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Implementation Strategy and Preliminary Outcomes. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2021;20:23259582211041424. https://doi.org/10.1177/23259582211041423.

Hochstatter KR, Akhtar WZ, Dietz S, Pe-Romashko K, Gustafson DH, Shah DV, et al. Potential Influences of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Drug Use and HIV Care Among People Living with HIV and Substance Use Disorders: Experience from a Pilot mHealth Intervention. AIDS Behav 2020:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02976-1.

Ennis N, Armas L, Butame S, Joshi H. Factors Impacting Video Telehealth Appointment Completion During COVID-19 Pandemic Among People Living with HIV in a Community-Based Health System. AIDS Behav 2021:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03394-7.

Sorbera M, Fischetti B, Khaimova R, Niewinski M, Wen K. Evaluation of virologic suppression rates during the COVID-19 pandemic with outpatient interdisciplinary HIV care. J Am Coll Clin Pharm JACCP. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/jac5.1422.

Campbell BR, Swoger S, Tabackman A, Hilgart E, Elliott B, Coffey S, et al. PositiveLinks and the COVID-19 Response: Importance of Low-Barrier Messaging for PLWH in Non-urban Virginia in a Crisis. AIDS Behav. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03294-w.

McKay T, Henne J, Gonzales G, Gavulic KA, Quarles R, Gallegos SG. Sexual Behavior Change Among Gay and Bisexual Men During the First COVID-19 Pandemic Wave in the United States. Sex Res Soc Policy J NSRC SR SP 2021:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-021-00625-3.

Kalichman SC, El-Krab R, Shkembi B, Kalichman MO, Eaton LA. Prejudicial beliefs and COVID-19 disruptions among sexual minority men living with and not living with HIV in a high SARS-CoV-2 prevalence area. Transl Behav Med. 2021;11:1310–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibab050.

Wion RK, Miller WR. The Impact of COVID-19 on HIV Self-Management, Affective Symptoms, and Stress in People Living with HIV in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2021;25:3034–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03335-4.

Sanchez TH, Zlotorzynska M, Rai M, Baral SD. Characterizing the Impact of COVID-19 on Men Who Have Sex with Men Across the United States in April, 2020. AIDS Behav 2020:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02894-2.

Nguyen AL, Davtyan M, Taylor J, Christensen C, Plankey M, Karpiak S, et al. Living With HIV During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Impacts for Older Adults in Palm Springs, California. AIDS Educ Prev Off Publ Int Soc AIDS Educ. 2021;33:265–75. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2021.33.4.265.

Qiao S, Li Z, Weissman S, Li X, Olatosi B, Davis C, et al. Disparity in HIV Service Interruption in the Outbreak of COVID-19 in South Carolina. AIDS Behav. 2021;25:49–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03013-x.

Shiau S, Krause KD, Valera P, Swaminathan S, Halkitis PN. The Burden of COVID-19 in People Living with HIV: A Syndemic Perspective. AIDS Behav. 2020;24:2244–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02871-9.

Winwood JJ, Fitzgerald L, Gardiner B, Hannan K, Howard C, Mutch A. Exploring the Social Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on People Living with HIV (PLHIV): A Scoping Review. AIDS Behav. 2021;25:4125–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03300-1.

Roberts ET, Mehrotra A. Assessment of Disparities in Digital Access Among Medicare Beneficiaries and Implications for Telemedicine. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1386–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2666.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge information specialist, Stella Seal, Williams H. Welch Medical Library, Johns Hopkins Medicine, who curated the search strategy and performed the initial literature search.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization (Diane Meyer, Jason E. Farley), Data curation (Diane Meyer), Formal analysis (Diane Meyer, Sarah E. Slone, Oluwabunmi Ogungbe, Brenice Duroseau), Writing-original draft (Diane Meyer), Writing-review and editing (Diane Meyer, Sarah E. Slone, Oluwabunmi Ogungbe, Brenice Duroseau, Jason E. Farley).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not Applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Meyer, D., Slone, S.E., Ogungbe, O. et al. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on HIV Healthcare Service Engagement, Treatment Adherence, and Viral Suppression in the United States: A Systematic Literature Review. AIDS Behav 27, 344–357 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-022-03771-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-022-03771-w