Abstract

Although Kenya nationally scaled up oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in May 2017, adolescent girls’ (AG, aged 15–19 years) and young women’s (YW, aged 20–24 years) PrEP use remains suboptimal. Thus, we analyzed PrEP consultations—interactions with a healthcare provider about PrEP—among Kenyan AGYW. In April-June 2018, AGYW enrolled in DREAMS in Kisumu County, Kenya self-reported their HIV-related knowledge, behaviors, and service use. Among HIV negative, sexually active AG (n = 154) and YW (n = 289), we examined associations between PrEP eligibility and PrEP consultations using prevalence ratios (PR, adjusted: aPR). Most AG (90.26%) and YW (94.12%) were PrEP-eligible due to inconsistent/no condom use, violence survivorship, or recent sexually transmitted infection symptoms. Between PrEP-eligible AG and YW, more YW were ever-orphaned (58.09%), ever-married (54.41%), ever-pregnant (80.88%), and out of school (78.31%); more PrEP-eligible YW reported PrEP consultations (41.18% vs. 24.46%, aPR = 1.51 [1.01–2.27]). AG who used PEP (post-exposure prophylaxis) reported more consultations (aPR = 5.63 [3.53–8.97]). Among YW, transactional sex engagers reported more consultations (58.62% vs. 39.09%, PR = 1.50 [1.06–2.12]), but only PEP use (aPR = 2.81 [2.30–3.43]) and multiple partnerships (aPR = 1.39 [1.06–1.82]) were independently associated with consultations. Consultations were lowest among those with 1 eligibility criterion (AG = 11.11%/YW = 27.18%). Comparatively, consultations were higher among AG and YW with 2 (aPR = 3.71 [1.64–8.39], PR = 1.60 [1.07–2.38], respectively) or ≥ 3 (aPR = 2.51 [1.09–5.78], PR = 2.05 [1.42–2.97], respectively) eligibility criteria. Though most AGYW were PrEP-eligible, PrEP consultations were rare and differed by age and vulnerability. In high-incidence settings, PrEP consultations should be conducted with all AGYW. PrEP provision guidelines must be re-assessed to accelerate AGYW’s PrEP access.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Despite geopolitical commitments, increased donor investments, and novel program delivery, adolescent girls (AG, aged 15–19 years) and young women (YW, aged 20–24 years) remain at disproportionate risk of HIV acquisition [1]. Globally, AGYW make up 75% of annual seroconversions among 15- to 24-year-olds, with an estimated 7000 AGYW seroconverting weekly. Despite being only 10% of sub-Saharan Africa’s population, AGYW account for 20% of the region’s seroconversions [2]. In Kenya, AGYW’s prevalence (2.6%) and incidence (approximately 12,500 seroconversions annually) are approximately double that of their male counterparts [3]. This gendered disparity is driven by life transitions, such as orphanhood [4,5,6], early marriage and pregnancy [6,7,8,9,10,11], and school dropout [12, 13]; not knowing a partner’s HIV status [14, 15]; behaviors, like substance use [7, 16,17,18], transactional sex [7, 19], multiple partnerships [7, 18], and inconsistent/no condom use [20, 21]; and experiences, including sexually transmitted infections (STIs) [12, 21] and survivorship of physical and/or sexual violence from intimate [22,23,24,25] and/or non-partners [22, 24, 25].

Oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has become a primary focus of HIV prevention efforts because it is safe and highly efficacious [26]. Given their risk, AGYW are a priority population for PrEP, yet research suggests that PrEP access, uptake, adherence, and continuation is low among AGYW [15, 27,28,29,30]. The HIV prevention field experienced a paradigm shift in May 2017, when—after a national pilot program [31]—PrEP became widely available to Kenyans, including AGYW. As of October 2021, an estimated 127,500 Kenyans have cumulatively initiated oral PrEP [32]. However, due to aggregated data sources, it is difficult to ascertain how many of these initiators are AGYW.

Along with demand, PrEP’s utility is conditional on its availability and provision. Per Dunbar et al., the oral PrEP cascade underscores that there must be synergy between service availability and screening, offer, and initiation processes for the total target population (i.e., “all seronegative [AGYW] at risk for HIV who could benefit from PrEP”) to start PrEP [33]. Because PrEP initiation, adherence, and continuation among AGYW is low [15, 27,28,29,30] and affected by low perceived risk and concerns of pill burden, partner disapproval, side effects, and stigma [34,35,36,37,38], researchers, program planners, and implementers have concentrated on the cascade’s downstream factors. While warranted, emphasis on these downstream elements has led to a dearth of information on upstream processes, knowledge that would help illuminate if and how vulnerable AGYW are being identified and offered PrEP services.

In this paper, we aimed to investigate AGYW’s PrEP eligibility and interactions with PrEP providers, insights that can inform service access, linkages, retention, and provision. First, we used the Ministry of Health’s (MOH) PrEP eligibility criteria to identify the total target population among AGYW enrolled in DREAMS (Determined, Resilient, Empowered, AIDS-Free, Mentored, Safe) in Kisumu County, Kenya. Then, among this total target population, we examined associations between individual and cumulative MOH PrEP eligibility criteria and PrEP consultations to identify correlates and trends. These findings have the potential to inform strategies that increase AGYW’s access to PrEP services; improve providers’ ability to identify vulnerable clients; strengthen service delivery; and, subsequently, reduce AGYW’s HIV acquisition risk.

Methods

Study Population and Sample

For this analysis, we used data on DREAMS enrollees who participated in the DREAMS Implementation Science study. Additional details regarding DREAMS and its methods are provided elsewhere [1, 39]. Briefly, DREAMS uses community-based safe space platforms to engage AGYW in activities related to positive sexual behaviors, self-efficacy, socioeconomic approaches, and sexual and reproductive health. In Kenya, DREAMS operates in seven counties with high HIV incidence—namely Kisumu, Homa Bay, Migori, Siaya, Nairobi, Kiambu, and Mombasa [40]. The DREAMS Implementation Science study was conducted in Kisumu County, an urban/peri-urban setting neighboring Lake Victoria, where the HIV prevalence among adults (aged 15–64 years) is 17.5%, almost four-times the national average of 4.9% [41].

Based on program eligibility criteria, DREAMS staff enrolled 15- to 24-year-old females into the program if they lived and intended to stay in the program catchment area. Using structured survey instruments, study personnel collected enrollees’ self-reported knowledge, attitudes, practices, and experiences related to HIV; sexual and reproductive health; and healthcare utilization at two survey rounds [42, 43]. Longitudinal findings on this cohort of AGYW are presented elsewhere [44]. Since PrEP was not available at round 1 (October–November 2016), we used round 2 (April-June 2018) data for this analysis. Because PrEP use is conditional on HIV seronegativity and sexual activity, we excluded AGYW from this analysis if they were living with HIV or sexually inexperienced (i.e., reported never having sex) or inactive (i.e., reported ever having sex but no reported sex partner in the last 12 months).

Measures

The variable definitions for all study measures are presented in Table 1.

PrEP Eligibility

Using Kenya’s MOH PrEP eligibility criteria [45, 46], we identified participants “at substantial risk of acquiring HIV.” These criteria included attempting to conceive while in a serodiscordant relationship, recurrent drug or alcohol use during sex, transactional sex engagement, recurrent post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) use, sex with a partner of unknown HIV status, multiple sexual partnerships, recent STI experience, survivorship of intimate partner violence (IPV) or gender-based violence (GBV), and inconsistent or no condom use. Per MOH guidelines, these eligibility criteria are framed within a 6-month recall period. Due to the wording used in the DREAMS survey, most eligibility criteria were measured as occurring in the last 12 months (Table 1). Like the MOH guidelines, if a participant had at least one criterion, we considered them eligible for PrEP and, thus, a member of the total target population.

Sample Characteristics

For stratification purposes, we dichotomized age to differentiate between AG (aged 15–19 years) and YW (aged 20–24 years) and examined characteristics that could affect participants’ risk, such as socioeconomic position; orphanhood, marital, pregnancy, and schooling status; perceived HIV risk; travel outside the community; and location. When investigating the outcome, we also explored clinic/hospital travel time, which we used to assess differential service access (Table 1).

Outcome

We analyzed participants’ reports of PrEP consultations using a composite measure that captured interactions with a PrEP provider that occurred ever or at the last clinic visit (Table 1). We included “ever” responses because the survey was administered (April-June 2018) approximately one year after PrEP scale up (May 2017). In the DREAMS program, 18–24-year-olds were targeted for PrEP provision, meaning those aged 18–19 years in the AG age group had a greater opportunity for PrEP consultations than those aged 15–17 years. To account for this difference, we created a covariate (program targeting) to signify AG who were aged < 18 years after adding 1 year to their baseline age (67.53% among AG). We took this approach to account for the time difference between Round 1 data collection and national scale-up of PrEP, approximately 6–7 months. Though PrEP consultations did not differ across program targeting categories among PrEP-eligible AG (24.44% vs. 24.47%, Chi-square = 0.00, p = 0.998), we included it as a covariate in all analyses that examined the outcome among AG to control for any residual effects.

Statistical Analysis

For all analyses, we used an age-stratified approach and α = 0.05 to assess statistical significance. When generating cross-tabulations, we calculated p-values using Pearson’s Chi-squared Test and Fisher’s Exact Test, when appropriate (i.e., an expected cell count is < 5). We also examined differences in medians among YW using the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test; for AG, we used the van Elteren Test [47], a stratified extension of the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test, to account for differential program targeting.

For regression analyses, we used generalized linear models (log link, Poisson family, Huber-White sandwich variance estimator) to generate unadjusted and adjusted prevalence ratios (PR and aPR, respectively). We used this approach because when the outcome is common (i.e., > 10% prevalence), prevalence ratios better approximate relative risk than odds ratios [48,49,50]. Using Spearman’s correlation (cut-off of 0.80 [51]) and variance inflation factors (cut-off of 10 [52]), we concluded that multicollinearity did not affect any of the multivariable models (Supplemental Table 1).

When investigating PrEP consultation correlates, we fitted a preliminary adjusted model using all characteristics and PrEP eligibility criteria with an unadjusted p < 0.05. Then, we used backward selection to remove the PrEP criterion with the largest p-value until all PrEP eligibility criteria were statistically significant; characteristics remained in the adjusted model regardless of their adjusted p-value.

When analyzing the relationship between PrEP consultations and cumulative of PrEP eligibility criteria, we trichotomized the criteria totals using the median as the midpoint. We conducted all analyses using Stata v16.

Ethics

All respondents provided written informed consent or assent and parental consent; emancipated minors (i.e., married, pregnant, or a parent) provided consent. Participants were compensated 300 Kenyan Shillings (approximately USD $3) for their time. Ethical approval of study protocols and procedures was obtained from the institutional review boards at the Population Council and Kenyatta National Hospital/University of Nairobi Ethics and Research Committee and National Commission for Science, Technology, & Innovation (NACOSTI). Columbia University provided a “not human subjects research” designation for this secondary data analysis (#AAAS8976).

Results

Of the 736 DREAMS enrollees interviewed at round 2, we excluded 39.81% (293/736) because they were living with HIV or unsure/non-responsive about their HIV status (n = 37), sexually inexperienced (n = 232), or sexually inactive (n = 24), resulting in an initial sample of 443: 154 AG and 289 YW.

Identification of the Total Target Population

Table 2 highlights the frequency of each PrEP criterion. Overall, AG and YW had similar proportions for most PrEP eligibility criteria. However, compared with YW, AG had fewer reports of alcohol use during sex (2.60% vs. 10.03%, Chi-Square = 8.06, p = 0.005) and inconsistent/no condom use (74.03% vs. 89.27%, Chi-Square = 17.36, p < 0.001). In total, 90.26% of AG (139/154) and 94.12% of YW (272/289) reported at least one criterion, making them eligible for PrEP.

Characteristics Associated with PrEP Eligibility Among AG and YW

Table 3 details characteristic differences by age group and PrEP eligibility. More PrEP-eligible AG reported high perceived HIV risk than PrEP-ineligible AG (24.46% vs. 0.00%, Fisher’s p = 0.043). All 5 AG who were currently pregnant were PrEP-eligible (data not shown).

Compared with their ineligible counterparts, more PrEP-eligible YW were ever-married (54.41% vs. 5.88%, Chi-Square = 15.09, p < 0.001), ever-pregnant (80.88% vs. 29.41%, Fisher’s p < 0.001), and out of school (78.31% vs. 41.18%, Fisher’s p = 0.002). Of the 18 currently pregnant YW, all were PrEP-eligible (data not shown). When a multivariable model (Model I) was fit with marital, pregnancy, and schooling status, an ever-pregnant status (aPR = 1.15 [1.02–1.30]) was the only factor significantly greater among PrEP-eligible YW.

Between PrEP-eligible AG and YW, fewer AG were ever-orphaned (41.73% vs. 58.09%, Chi-Square = 9.88, p = 0.002), ever-married (16.55% vs. 54.41%, Chi-Square = 54.29, p < 0.001), ever-pregnant (38.85% vs. 80.88%, Chi-Square = 73.14, p < 0.001), and out of school (47.48% vs. 78.31%, Chi-Square = 40.10, p < 0.001). When examined together in a multivariable model (Model II), ever-married (aPR = 0.48 [0.30–0.77]), ever-pregnant (aPR = 0.52 [0.38–0.72]), and out-of-school status (aPR = 0.72 [0.56–0.94]) remained significant.

Examination of PrEP Consultation Correlates Among PrEP-eligible AG and YW

Table 4 presents findings related to PrEP consultations. Of 139 PrEP-eligible AG, only 24.46% (34/139) reported PrEP consultations, while 41.18% of PrEP-eligible YW (112/272) reported consultations. Compared with AG, YW reported more PrEP consultations (aPR = 1.68 [1.15–2.47], controlling for program targeting), even after controlling (Model III) for intergroup differences (orphanhood, marital, pregnancy, and schooling status and program targeting: aPR = 1.51 [1.01–2.27]).

Among PrEP-eligible AG, travel outside the community was the only characteristic associated with PrEP consultations. Specifically, PrEP-eligible AG who frequently (≥ 1 per month) traveled outside the community reported more PrEP consultations (aPR = 2.04 [1.13–3.68], controlling for program targeting) than infrequent (≤ 1 × year) travelers. Regarding PrEP eligibility criteria, PrEP-eligible AG who were recurrent PEP users reported more PrEP consultations (93.75% vs. 15.45%, z = 8.15, p < 0.001). After controlling for travel outside the community and program targeting, this association remained (aPR = 5.63 [3.53–8.97], [Model IV]).

For PrEP-eligible YW, PrEP consultations were not associated with socioeconomic position; orphanhood, marital, pregnancy, and schooling status; perceived HIV risk; travel outside the community; location; or clinic/hospital travel time. PrEP consultations were higher among YW who reported transactional sex (58.62% vs. 39.09%, Chi-Square = 4.08, p = 0.043), recurrent PEP use (97.22% vs. 32.63%, Chi-Square = 53.81, p < 0.001), and multiple sexual partners (62.79% vs. 37.12%, Chi-Square = 9.85, p = 0.002). The initial adjusted model included these three criteria (Model V): after the removal of transactional sex per our model building approach, recurrent PEP use (aPR = 2.81 [2.30–3.43]) and multiple sexual partnerships (aPR = 1.39 [1.06–1.82]) were independently associated with PrEP consultations (Model VI).

PrEP Consultations Among PrEP-Eligible AG and YW by Cumulative PrEP Eligibility Criteria

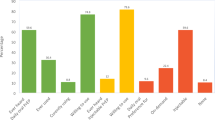

Figure 1 showcases the relationship between PrEP consultations and the cumulative number of PrEP eligibility criteria. The median number of criteria among both PrEP-eligible AG and YW was 2 (IQR: 1–3). While the median number of criteria by PrEP consultation category was similar between AG (Consulted: 2 [IQR: 2–4], Not Consulted: 1 [IQR: 1–3]) and YW (Consulted: 2 [IQR: 1.5–4], Not Consulted: 2 [IQR: 1–2]), there were within-group differences for both AG (z = − 3.204, p = 0.001) and YW (z = − 4.281, p < 0.001). In absolute terms, the number of consultations decrease in AG and YW after 2 criteria (Fig. 1A, B). Relatively, PrEP consultations were low (i.e., < 50%) for most PrEP eligibility criteria totals in each age group (Fig. 1A–D). However, though there was no apparent relationship for AG (Fig. 1A, C), the proportion of PrEP consultations among YW gradually increased as the number of PrEP eligibility criteria increased (Fig. 1B, D).

Using the categorized totals, AG with 2 or ≥ 3 PrEP eligibility criteria were more likely to report a PrEP consultation (aPR = 3.71 [1.64–8.39] and aPR = 2.51 [1.09–5.78], respectively) than AG with 1 criterion (Fig. 1E)—after controlling for differential program targeting and travel outside the community, which differed significantly by outcome status (Table 2). Similarly, YW with 2 (PR = 1.60 [1.07–2.38]) or ≥ 3 (PR = 2.05 [1.42–2.97]) criteria were more likely to report PrEP consultations (Fig. 1F).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this analysis is one of the first to use an age-stratified approach to examine AGYW’s connection to PrEP services by assessing the Kenya MOH’s PrEP eligibility criteria. Almost all AGYW had ≥ 1 MOH PrEP eligibility criteria and were, therefore, eligible for PrEP. However, few PrEP-eligible AGYW reported PrEP consultations, and consultations were significantly lower among AG than YW, even after accounting for intergroup sociodemographic differences (orphanhood, marital, pregnancy, and schooling status) and AG’s differential program targeting. For correlates of PrEP consultations, AG who were PEP users reported more screenings, and YW who used PEP and had multiple sex partners reported greater screenings. Though low overall, reports of PrEP consultations were higher among AG and YW with 2 or 3–7 PrEP eligibility criteria compared with 1 criterion. These findings imply that despite their high HIV risk, AGYW’s access to PrEP was limited, necessitating operational changes and capacity strengthening efforts to improve providers’ ability to identify clients with high HIV vulnerability and increase AGYW’s access to PrEP services.

By reporting one or more MOH criteria, almost all AGYW participants were considered at risk of HIV acquisition, with the three most common criteria being inconsistent/no condom use, ongoing IPV/GBV, and STI symptoms. Along with a link to HIV risk [20, 22, 23, 25, 53, 54], these risk factors are fueled by gender and power inequality [55,56,57,58]. In gender-inequitable environments, AGYW are more likely to encounter failed condom negotiations and violence perpetuated by intimate partners and/or strangers—which expose AGYW to STIs and mediate other negative health and psychological outcomes [17, 22, 58, 59]. Thus, activities to increase AGYW’s PrEP access must be complemented with efforts to engage males and couples in dialogue about PrEP, gender equality, and egalitarian relationships. Evidence from South Africa, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe support that as relationship dynamics equalize and male partners’ knowledge of PrEP increase, AGYW’s PrEP-related outcomes (e.g., initiation, adherence, and continuation) improve, too [35, 60, 61].

Among PrEP-eligible AG and YW, numerous characteristics were associated with HIV vulnerability. Albeit only in the unadjusted analyses, we discovered that more PrEP-eligible than -ineligible AG had high perceived HIV risk, a promising finding since risk perception influences care-seeking behaviors [62]. Consistent with the current evidence, we also learned that more PrEP-eligible YW were ever-married and out of school than PrEP-ineligible YW [13, 53], reinforcing their continued focus in AGYW HIV prevention programming. Relatedly, pregnancy history was independently associated with substantial HIV risk [17, 37, 63] in YW, underscoring the need to integrate PrEP services into sexual and reproductive services (e.g., sexual health, family planning, maternal and child health) to avoid missed opportunities and ensure comprehensive coverage [15, 17, 64, 65]. When compared with PrEP-eligible AG, many of these factors (out-of-school, ever-married, ever-pregnant status) plus orphanhood were higher in PrEP-eligible YW. Considering the age difference, YW have greater opportunity to experience these life transitions, so these findings are not unexpected. Novel analytic methods, such as latent class analysis, should be used in the future to illuminate how synergies between AGYW’s multiple vulnerabilities manifest and relate to HIV risk and service access and use.

Despite ubiquitous risk, most AGYW did not report PrEP consultations. Evidence from other settings and contexts offer some potential logistical explanations for this disparity: limited human resources, suboptimal processes, and high client volumes [66,67,68]. Qualitative research from Kenya shows that heavy workloads truncate client-provider interactions and impact service provision, causing providers to focus solely on the client’s direct request rather than offer additional services or inquire about other health concerns [29]. Additionally, evidence from South Africa and the United States support that providers’ PrEP knowledge, awareness, and assumptions [69, 70] can affect service provision. Findings from Tanzania reinforce that provider- and facility-level capacity strengthening activities are also vital to ensuring providers are ready, willing, and able to offer PrEP services [71]. To confirm PrEP services are well-integrated and not a burden on health care providers or clients, closer examination of facility-level staffing, workflows, and procedures is recommended.

Despite similar risk distributions, PrEP consultations—though low overall—were significantly lower in AG than YW, even after controlling for differences in program targeting among AG. Provider attitudes could have contributed to this difference [72, 73]. Research from Kenya suggests that providers are concerned about prescribing AGYW oral PrEP because it could lead to risky behaviors, such as multiple sex partners and condomless sex [74, 75], a sentiment corroborated by qualitative interviews with providers in Tanzania [71]. Kenyan providers have also expressed that AG should be offered abstinence counseling rather than PrEP, AG lack the responsibility required for PrEP adherence, and providing PrEP to AG would cause community backlash [74, 75], a key reason why DREAMS chose not to target 15–17-year-olds for PrEP provision. Alternatively, consultations might have been lower because AG were uncomfortable disclosing behaviors and experiences due to provider mistrust, fear of sexuality-based stigma, or negative PrEP perceptions [29, 76, 77]. To increase the likelihood of disclosure, AGYW should be attended to by a similar-aged, same-gender provider in a private location; in addition, providers should be given sensitivity training on AGYW’s sexuality, behavior, and risk. There must also be activities and dialogue to build mutual respect and trust between AGYW and providers. These implementation bottlenecks and barriers necessitate additional insight into other client- and provider-side factors that affect AGYW’s ability to make informed PrEP decisions and providers’ capability to offer quality services [78].

PEP use was a correlate of PrEP consultations in AG and YW. However, due to PEP and PrEP’s inherent clinical ties, it is difficult to isolate the effect of PEP use. Per MOH guidelines, PEP users who are seronegative at the end of the medication regimen are to immediately transition to PrEP [45]; it is also possible that AGYW sought out PrEP services but were, instead, prescribed PEP due to a recent high-risk encounter. This temporal ambiguity also complicates the finding that multiple partnerships was correlated with PrEP consultations among YW (i.e., did YW with multiple partners seek out PrEP services, or does PEP mediate some of the pathways between multiple partnerships and PrEP consultations?) Alternatively, YW with multiple partners could have frequented clinics/visited providers more often for HIV testing or other services, increasing their chances of engaging with providers about PrEP. Although we cannot disentangle these relationships, this PEP-PrEP connection suggests that AGYW with an existing linkage to the healthcare system were more likely to report PrEP consultations. Due to structural and community barriers, accessing healthcare systems can be precarious for AGYW [29, 79, 80]. Rather than have it siloed in clinics, PrEP services might be best delivered using community-based approaches—such as mobile or pop-up clinics—that bring care to areas that AGYW frequent.

When we examined PrEP eligibility criteria cumulatively, we discovered that AG and YW with > 1 criteria were more likely to report PrEP consultations than those with 1 criterion. While it is encouraging that AGYW with multiple vulnerabilities reported more consultations, this finding also implies that unless multiple risk factors were present, PrEP consultations were relatively rare. Moreover, it is possible that these criteria were not contemporaneous and, instead, occurred at separate time points; thus, we cannot deduce how many criteria were met when AGYW interacted with providers. Regardless, since only one criterion is needed for PrEP eligibility, these findings highlight the need for improved risk identification tools, tactics, and approaches to help AGYW consider their HIV risk and PrEP need, as well as help providers effectively counsel AGYW on PrEP.

While our study provides interesting insights, it is not without limitations. First, we could have underestimated risk since we could not measure injection drug use. Secondly, our use of definitional substitutions for the MOH’s PrEP eligibility criteria could have led to misclassification, potentially biasing our results. Subsequent research should use the same verbiage and timeframe as the MOH’s guidelines. Thirdly, because we used self-reported data, we cannot overlook the possibility of social desirability and/or recall bias. Fourthly, due to cross-sectional data, we cannot assess when behaviors or experiences occurred, relative to each other and PrEP consultations. Future research should employ a longitudinal design to examine the temporality of risk factors. Fifthly, due to limitations with our questionnaire, we could not assess oral PrEP offers and initiations outside the context of DREAMS, and no questions asked about adherence or continuation. This limitation warrants additional research into the connection between PrEP eligibility, consultations, and outcomes along the PrEP cascade. Lastly, this analysis used data collected approximately one year after national PrEP scale up; though we assumed that PrEP services were readily available since Kisumu County was a pilot site, it is possible that access to PrEP services was limited. Future studies should consider illuminating service availability by using spatial analyses.

Conclusions

While efficacious, oral PrEP’s potential is wasted if it is inaccessible to individuals at substantial risk of HIV acquisition. To understand AGYW’s access to PrEP, we examined their PrEP eligibility and reports of PrEP consultations. Almost all AGYW in our sample were eligible, yet most did not report engaging in a PrEP consultation, and consultations were lower among AG than YW. Correlates of PrEP consultations included PEP use for, both, AG and YW and multiple sexual partnerships for YW, only. While PrEP consultations increased as the number of criteria increased, consultations were low (i.e., < 50%) in most criteria totals. The limited number of reported PrEP consultations implies that AGYW’s access to PrEP was low, necessitating implementation improvements and tools or strategies to improve risk identification. Further, efforts must be taken to ensure that in high HIV-transmission settings, PrEP consultations are offered to all AGYW, increasing the chances that AGYW—no matter their number of vulnerabilities—have the opportunity to decrease their HIV acquisition risk.

Data Availability

All the data are available on Dataverse.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Saul J, Bachman G, Allen S, Toiv NF, Cooney C, Beamon TA. The DREAMS core package of interventions: a comprehensive approach to preventing HIV among adolescent girls and young women. PLoS One. 2018;13(12).

UNAIDS. Women and HIV. A spotlight on adolescent girls and young women. 2019.

National AIDS and STI Control Program. Kenya HIV estimates: Report 2018. Nairobi: Ministry of Health, Kenya, 2018.

Birdthistle IJ, Floyd S, Machingura A, Mudziwapasi N, Gregson S, Glynn JR. From affected to infected? Orphanhood and HIV risk among female adolescents in urban Zimbabwe. AIDS. 2008;22(6):759–66.

Nyirenda M, McGrath N, Newell M-L. Gender differentials in the impact of parental death: adolescent’s sexual behaviour and risk of HIV infection in rural South Africa. Vulner Children Youth Stud. 2010;5(3):284–96.

Karim QA, Kharsany AB, Leask K, Ntombela F, Humphries H, Frohlich JA, et al. Prevalence of HIV, HSV-2 and pregnancy among high school students in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: a bio-behavioural cross-sectional survey. Sex Transm Infect. 2014;90(8):620–6.

Price JT, Rosenberg NE, Vansia D, Phanga T, Bhushan NL, Maseko B, et al. Predictors of HIV, HIV risk perception, and HIV worry among adolescent girls and young women in Lilongwe, Malawi. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;77(1):53.

Pascoe SJ, Langhaug LF, Mavhu W, Hargreaves J, Jaffar S, Hayes R, et al. Poverty, food insufficiency and HIV infection and sexual behaviour among young rural Zimbabwean women. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(1):e0115290.

Clark S. Early marriage and HIV risks in sub-Saharan Africa. Stud Fam Plann. 2004;35(3):149–60.

Stephenson R, Simon C, Finneran C. Community factors shaping early age at first sex among adolescents in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Malawi, and Uganda. J Health Popul Nutr. 2014;32(2):161.

Christofides NJ, Jewkes RK, Dunkle KL, Nduna M, Shai NJ, Sterk C. Early adolescent pregnancy increases risk of incident HIV infection in the Eastern Cape, South Africa: a longitudinal study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17(1):18585.

Santelli JS, Edelstein ZR, Mathur S, Wei Y, Zhang W, Orr MG, et al. Behavioral, biological, and demographic risk and protective factors for new HIV infections among youth, Rakai, Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(3):393.

Hargreaves JR, Bonell CP, Boler T, Boccia D, Birdthistle I, Fletcher A, et al. Systematic review exploring time trends in the association between educational attainment and risk of HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2008;22(3):403–14.

Reynolds Z, Gottert A, Luben E, Mamba B, Shabangu P, Dlamini N, et al. Who are the male partners of adolescent girls and young women in Swaziland? Analysis of survey data from community venues across 19 DREAMS districts. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(9):e0203208.

Mugwanya KK, Pintye J, Kinuthia J, Abuna F, Lagat H, Begnel ER, et al. Integrating preexposure prophylaxis delivery in routine family planning clinics: a feasibility programmatic evaluation in Kenya. PLoS Med. 2019;16(9):e1002885.

Balkus JE, Brown E, Palanee T, Nair G, Gafoor Z, Zhang J, et al. An empiric HIV risk scoring tool to predict HIV-1 acquisition in African women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(3):333.

Larsen A, Kinuthia J, Lagat H, Sila J, Abuna F, Kohler P, et al. Depression and HIV risk behaviors among adolescent girls and young women seeking family planning services in Western Kenya. Int J STD AIDS. 2020;31(7):652–64.

Mabaso M, Sokhela Z, Mohlabane N, Chibi B, Zuma K, Simbayi L. Determinants of HIV infection among adolescent girls and young women aged 15–24 years in South Africa: a 2012 population-based national household survey. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1–7.

Jewkes R, Dunkle K, Nduna M, Shai NJ. Transactional sex and HIV incidence in a cohort of young women in the stepping stones trial. Journal of AIDS and Clinical research. 2012;3(5).

UNAIDS. HIV Prevention among adolescent girls and young women. UNAIDS, 2016.

Pettifor AE, Rees HV, Kleinschmidt I, Steffenson AE, MacPhail C, Hlongwa-Madikizela L, et al. Young people’s sexual health in South Africa: HIV prevalence and sexual behaviors from a nationally representative household survey. AIDS. 2005;19(14):1525–34.

Mathur S, Okal J, Musheke M, Pilgrim N, Kishor Patel S, Bhattacharya R, et al. High rates of sexual violence by both intimate and non-intimate partners experienced by adolescent girls and young women in Kenya and Zambia: Findings around violence and other negative health outcomes. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(9):e0203929.

Li Y, Marshall CM, Rees HC, Nunez A, Ezeanolue EE, Ehiri JE. Intimate partner violence and HIV infection among women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17(1):18845.

Decker MR, Peitzmeier S, Olumide A, Acharya R, Ojengbede O, Covarrubias L, et al. Prevalence and health impact of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence among female adolescents aged 15–19 years in vulnerable urban environments: a multi-country study. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(6):S58–67.

Bhattacharjee P, Ma H, Musyoki H, Cheuk E, Isac S, Njiraini M, et al. Prevalence and patterns of gender-based violence across adolescent girls and young women in Mombasa. Kenya BMC Women’s Health. 2020;20(1):1–11.

Masho SW, Wang C-L, Nixon DE. Review of tenofovir-emtricitabine. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2007;3(6):1097.

Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, Agot K, Lombaard J, Kapiga S, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):411–22.

Marrazzo JM, Ramjee G, Richardson BA, Gomez K, Mgodi N, Nair G, et al. Tenofovir-based preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(6):509–18.

Were D, Musau A, Mutegi J, Ongwen P, Manguro G, Kamau M, et al. Using a HIV prevention cascade for identifying missed opportunities in PrEP delivery in Kenya: results from a programmatic surveillance study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23:e25537.

de Dieu Tapsoba J, Zangeneh SZ, Appelmans E, Pasalar S, Mori K, Peng L, et al. Persistence of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among adolescent girls and young women initiating PrEP for HIV prevention in Kenya. AIDS Care. 2020:1–9.

Masyuko S, Mukui I, Njathi O, Kimani M, Oluoch P, Wamicwe J, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis rollout in a national public sector program: the Kenyan case study. Sexual health. 2018;15(6):578–86.

AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition. PrEP Watch: Kenya 2020. https://www.prepwatch.org/country/kenya/. Accessed 15 March 2020.

Dunbar MS, Kripke K, Haberer J, Castor D, Dalal S, Mukoma W, et al. Understanding and measuring uptake and coverage of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis delivery among adolescent girls and young women in sub-Saharan Africa. Sexual health. 2018;15(6):513–21.

Velloza J, Khoza N, Scorgie F, Chitukuta M, Mutero P, Mutiti K, et al. The influence of HIV-related stigma on PrEP disclosure and adherence among adolescent girls and young women in HPTN 082: a qualitative study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23(3):e25463.

Gombe MM, Cakouros BE, Ncube G, Zwangobani N, Mareke P, Mkwamba A, et al. Key barriers and enablers associated with uptake and continuation of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in the public sector in Zimbabwe: Qualitative perspectives of general population clients at high risk for HIV. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(1):e0227632.

Camlin CS, Koss CA, Getahun M, Owino L, Itiakorit H, Akatukwasa C, et al. Understanding demand for PrEP and early experiences of PrEP use among young adults in rural Kenya and Uganda: a qualitative study. AIDS and Behavior. 2020:1–14.

Sila J, Larsen AM, Kinuthia J, Owiti G, Abuna F, Kohler PK, et al. High awareness, yet low uptake, of pre-exposure prophylaxis among adolescent girls and young women within family planning clinics in Kenya. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2020;34(8):336–43.

Maseko B, Hill LM, Phanga T, Bhushan N, Vansia D, Kamtsendero L, et al. Perceptions of and interest in HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis use among adolescent girls and young women in Lilongwe, Malawi. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(1):e0226062.

Mathur S, Pilgrim N, Patel SK, Okal J, Mwapasa V, Chipeta E, et al. HIV vulnerability among adolescent girls and young women: a multi-country latent class analysis approach. Int J Public Health. 2020;1–13.

The United States Department of State. Kenya: DREAMS Overview (FY 2016–2021). 2020.

National AIDS and STI Control Program. Preliminary KENPHIA 2018 Report. Nairobi: Ministry of Health, Kenya, 2020.

Mathur S, Okal J, Pilgrim N, Matheka J, Jani N, Pulerwitz J. DREAMS implementation science: Round 2 Data, Kenya. V1 ed: Harvard Dataverse; 2021.

Mathur S, Okal J, Pilgrim N, Matheka J, Jani N, Pulerwitz J. DREAMS implementation science: All Round 1 Data, Kenya. In: Population C, editor. V2 ed: Harvard Dataverse; 2021.

Population Council. “Program effects of DREAMS among adolescent girls and young women in Kisumu County, Kenya: findings from DREAMS implementation science research. DREAMS Kenya Results Brief,. 2020.

National AIDS & STI Control Program. Guidelines of Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection in Kenya. Nairobi: Ministry of Health, Kenya, 2018.

National AIDS and STI Control Program. Pre-exposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection: A Toolkit for Providers. Nairobi: Ministry of Health, Kenya, 2017.

LaVange LM, Koch GG. Rank score tests. Circulation. 2006;114(23):2528–33.

Zhang J, Kai FY. What’s the relative risk?: A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998;280(19):1690–1.

Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3(1):1–13.

Lovasi GS, Underhill LJ, Jack D, Richards C, Weiss C, Rundle A. At odds: concerns raised by using odds ratios for continuous or common dichotomous outcomes in research on physical activity and obesity. Open Epidemiol J. 2012;5:13.

Berry WD, Feldman S, Stanley Feldman D. Multiple regression in practice: Sage; 1985.

Neter J, Kutner MH, Nachtsheim CJ, Wasserman W. Applied linear statistical models. 1996.

Ziraba A, Orindi B, Muuo S, Floyd S, Birdthistle IJ, Mumah J, et al. Understanding HIV risks among adolescent girls and young women in informal settlements of Nairobi, Kenya: Lessons for DREAMS. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(5):e0197479.

Hunter DJ, Maggwa BN, Mati JK, Tukei PM, Mbugua S. Sexual behavior, sexually transmitted diseases, male circumcision and risk on HIV infection among women in Nairobi, Kenya. AIDS. 1994.

Pulerwitz J, Mathur S, Woznica D. How empowered are girls/young women in their sexual relationships? Relationship power, HIV risk, and partner violence in Kenya. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(7):e0199733.

Longfield K, Glick A, Waithaka M, Berman J. Relationships between older men and younger women: implications for STIs/HIV in Kenya. Stud Fam Plann. 2004;35(2):125–34.

Orindi BO, Maina BW, Muuo SW, Birdthistle I, Carter DJ, Floyd S, et al. Experiences of violence among adolescent girls and young women in Nairobi’s informal settlements prior to scale-up of the DREAMS partnership: prevalence, severity and predictors. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(4):e0231737.

Muluneh MD, Francis L, Agho K, Stulz V. A systematic review and meta-analysis of associated factors of gender-based violence against women in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(9):4407.

Fonck K, Kidula N, Kirui P, Ndinya-Achola J, Bwayo J, Claeys P, et al. Pattern of sexually transmitted diseases and risk factors among women attending an STD referral clinic in Nairobi, Kenya. Sex Transm Dis. 2000;27(7):417–23.

Holmes LE, Kaufman MR, Casella A, Mudavanhu M, Mutunga L, Polzer T, et al. Qualitative characterizations of relationships among South African adolescent girls and young women and male partners: implications for engagement across HIV self-testing and pre-exposure prophylaxis prevention cascades. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23:e25521.

Jani N, Mathur S, Kahabuka C, Makyao N, Pilgrim N. Relationship dynamics and anticipated stigma: Key considerations for PrEP use among Tanzanian adolescent girls and young women and male partners. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(2):e0246717.

Schaefer R, Gregson S, Fearon E, Hensen B, Hallett TB, Hargreaves JR. HIV prevention cascades: a unifying framework to replicate the successes of treatment cascades. The Lancet HIV. 2019;6(1):e60–6.

Zulaika G, Nyothach E, van Eijk AM, Obor D, Mason L, Wang D, et al. Factors associated with the prevalence of HIV, HSV-2, pregnancy, and reported sexual activity among adolescent girls in rural western Kenya: a cross-sectional analysis of baseline data in a cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2021;18(9):e1003756.

Rousseau E, Katz AW, O’Rourke S, Bekker L-G, Delany-Moretlwe S, Bukusi E, et al. Adolescent girls and young women’s PrEP-user journey during an implementation science study in South Africa and Kenya. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(10):e0258542.

Bhavaraju N, Wilcher R, Regeru RN, Mullick S, Mahaka I, Rodrigues J, et al. Integrating oral PrEP into family planning services for women in sub-Saharan Africa: findings from a multi-country landscape analysis. Front Reproduct Health. 2021;3:29.

Stime KJ, Garrett N, Sookrajh Y, Dorward J, Dlamini N, Olowolagba A, et al. Clinic flow for STI, HIV, and TB patients in an urban infectious disease clinic offering point-of-care testing services in Durban. South Africa BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):1–9.

Wagenaar BH, Gimbel S, Hoek R, Pfeiffer J, Michel C, Cuembelo F, et al. Wait and consult times for primary healthcare services in central Mozambique: a time-motion study. Glob Health Action. 2016;9(1):31980.

Alamo ST, Wagner GJ, Ouma J, Sunday P, Marie L, Colebunders R, et al. Strategies for optimizing clinic efficiency in a community-based antiretroviral treatment programme in Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(1):274–83.

Hosek S, Celum C, Wilson CM, Kapogiannis B, Delany-Moretlwe S, Bekker LG. Preventing HIV among adolescents with oral PrEP: observations and challenges in the United States and South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19:21107.

Calabrese SK, Magnus M, Mayer KH, Krakower DS, Eldahan AI, Hawkins LAG, et al. “Support your client at the space that they’re in”: HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) prescribers’ perspectives on PrEP-related risk compensation. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2017;31(4):196–204.

Pilgrim N, Jani N, Mathur S, Kahabuka C, Saria V, Makyao N, et al. Provider perspectives on PrEP for adolescent girls and young women in Tanzania: The role of provider biases and quality of care. PloS one. 2018;13(4).

Godia PM, Olenja JM, Lavussa JA, Quinney D, Hofman JJ, Van Den Broek N. Sexual reproductive health service provision to young people in Kenya; health service providers’ experiences. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):476.

Hagey JM, Akama E, Ayieko J, Bukusi EA, Cohen CR, Patel RC. Barriers and facilitators adolescent females living with HIV face in accessing contraceptive services: a qualitative assessment of providers’ perceptions in western Kenya. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18(1):20123.

Mireku M, Kyongo J, Stankevitz K, Jeckonia P, Ikahu A, Otiso L, et al., editors. Health care providers’ knowledge, attitudes and practices towards provision of PrEP to adolescent girls and young women in Kenya. HIV Res Prevent Conf; 2018.

Lanham M, Stankevitz K, Ridgeway K, Mireku M, Nhamo D, Pillay D, et al. Healthcare Providers’ attitudes and experiences delivering oral PrEP to adolescent girls and young women: implementation research to inform PrEP scaleup in Kenya, South Africa, and Zimbabwe. 2019.

Godia PM, Olenja JM, Hofman JJ, Van Den Broek N. Young people’s perception of sexual and reproductive health services in Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):172.

Robert K, Maryline M, Jordan K, Lina D, Helgar M, Annrita I, et al. Factors influencing access of HIV and sexual and reproductive health services among adolescent key populations in Kenya. Int J Public Health. 2020:1–8.

Mathur S, Pilgrim N, Pulerwitz J. PrEP introduction for adolescent girls and young women. Lancet HIV. 2016;3(9):e406–8.

Escudero JN, Dettinger JC, Pintye J, Kinuthia J, Lagat H, Abuna F, et al. Community perceptions about use of pre-exposure prophylaxis among adolescent girls and young women in Kenya. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2020;31(6):669–77.

Lane J, Brezak A, Patel P, Verani AR, Benech I, Katz A. Policy considerations for scaling up access to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis for adolescent girls and young women: examples from Kenya, South Africa, and Uganda. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2021;36(5):1789–808.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the in-country implementing partners (APHIAPlus/Afya Ziwani/PATH, I Choose Life, Make Me Smile) and team of research coordinators and data collectors. Our deepest gratitude goes to the study participants, for if not for their involvement, this research would not be possible. We would also like to thank Domonique Reed, Kavitha Ganesan, Sarah Gutkind, Sumera Aziz, Brandi Vollmer, Pich Seekaew, Lauren Houghton, Shadiya Moss, and Erik Jorgenson for their review of earlier versions of this manuscript.

Funding

Funding support for this study was provided by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1136778). Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32AI114398. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception: CJH, SM; data analysis and manuscript preparation: CJH, SM; data collection: JO; oversaw program implementation: HA, OMD, RO MO; manuscript review, comments, and edits: CJH, SM, HA, OMD, RO, MO, JO. All authors (CJH, SM, HA, OMD, RO, MO, JO) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Ethical approval of study protocols and procedures was obtained from the institutional review boards at the Population Council and Kenyatta National Hospital/University of Nairobi Ethics and Research Committee and National Commission for Science, Technology, & Innovation (NACOSTI). Columbia University provided a “not human subjects research” designation for this secondary data analysis (#AAAS8976).

Consent to Participate

All respondents provided written informed consent or assent and parental consent; emancipated minors (i.e., married, pregnant, or a parent) provided consent.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Heck, C.J., Mathur, S., Alwang’a, H. et al. Oral PrEP Consultations Among Adolescent Girls and Young Women in Kisumu County, Kenya: Insights from the DREAMS Program. AIDS Behav 26, 2516–2530 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-022-03590-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-022-03590-z