Abstract

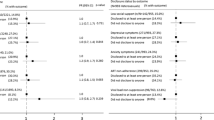

We investigated the effect of early antiretroviral treatment (ART) initiation on HIV status disclosure and social support in a cluster-randomized, treatment-as-prevention (TasP) trial in rural South Africa. Individuals identified HIV-positive after home-based testing were referred to trial clinics where they were invited to initiate ART immediately irrespective of CD4 count (intervention arm) or following national guidelines (control arm). We used Poisson mixed effects models to assess the independent effects of (a) time since baseline clinical visit, (b) trial arm, and (c) ART initiation on HIV disclosure (n = 182) and social support (n = 152) among participants with a CD4 count > 500 cells/mm3 at baseline. Disclosure and social support significantly improved over follow-up in both arms. Disclosure was higher (incidence rate ratio [95% confidence interval]: 1.24 [1.04; 1.48]), and social support increased faster (1.22 [1.02; 1.46]) in the intervention arm than in the control arm. ART initiation improved both disclosure and social support (1.50 [1.28; 1.75] and 1.34 [1.12; 1.61], respectively), a stronger effect being seen in the intervention arm for social support (1.50 [1.12; 2.01]). Besides clinical benefits, early ART initiation may also improve psychosocial outcomes. This should further encourage countries to implement universal test-and-treat strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Moir S, Buckner CM, Ho J, Wang W, Chen J, Waldner AJ, et al. B cells in early and chronic HIV infection: evidence for preservation of immune function associated with early initiation of antiretroviral therapy. Blood. 2010;116(25):5571–9.

Schuetz A, Deleage C, Sereti I, Rerknimitr R, Phanuphak N, Phuang-Ngern Y, et al. Initiation of ART during early acute HIV infection preserves mucosal Th17 function and reverses HIV-related immune activation. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(12):e1004543.

Ford N, Migone C, Calmy A, Kerschberger B, Kanters S, Nsanzimana S, et al. Benefits and risks of rapid initiation of antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Lond Engl. 2018;32(1):17.

Donnell D, Baeten JM, Kiarie J, Thomas KK, Stevens W, Cohen CR, et al. Heterosexual HIV-1 transmission after initiation of antiretroviral therapy: a prospective cohort analysis. Lancet. 2010;375(9731):2092–8.

Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505.

Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents: recommendations for a public health approach—2010 revision [Internet]. [cité 5 mars 2019]. Disponible sur: https://apps-who-int.gate2.inist.fr/iris/handle/10665/44379

WHO | Consolidated ARV guidelines 2013 [Internet]. WHO. [cité 5 mars 2019]. Disponible sur: https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/arv2013/art/statartadolescents_rationale/en/

World Health Organization, World Health Organization, Department of HIV/AIDS. Guideline on when to start antiretroviral therapy and on pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV. [Internet]. 2015 [cité 8 mars 2019]. Disponible sur: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK327115/

Tanser F, Bärnighausen T, Grapsa E, Zaidi J, Newell M-L. High coverage of ART associated with decline in risk of HIV acquisition in rural KwaZulu-Natal. S Afr Sci. 2013;339(6122):966–71.

Granich RM, Gilks CF, Dye C, De Cock KM, Williams BG. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):48–57.

Phillips AN, Cambiano V, Miners A, Lampe FC, Rodger A, Nakagawa F, et al. Potential impact on HIV incidence of higher HIV testing rates and earlier antiretroviral therapy initiation in MSM. AIDS Lond Engl. 2015;29(14):1855.

Iwuji CC, Orne-Gliemann J, Larmarange J, Balestre E, Thiebaut R, Tanser F, et al. Universal test and treat and the HIV epidemic in rural South Africa: a phase 4, open-label, community cluster randomised trial. Lancet HIV. 2018;5(3):e116–25.

Hayes R, Ayles H, Beyers N, Sabapathy K, Floyd S, Shanaube K, et al. HPTN 071 (PopART): rationale and design of a cluster-randomised trial of the population impact of an HIV combination prevention intervention including universal testing and treatment–a study protocol for a cluster randomised trial. Trials. 2014;15(1):57.

Sustainable East Africa Research in Community Health—Tabular View—ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. [cité 5 mars 2019]. Disponible sur: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT01864603

Perriat D, Balzer L, Hayes R, Lockman S, Walsh F, Ayles H, et al. Comparative assessment of five trials of universal HIV testing and treatment in sub-Saharan Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21(1):e25048.

Abdool-Karim SS. HIV-1 epidemic control—insights from test-and-treat trials. Mass Medical Soc. 2019;381:286–8.

Makhema J, Wirth KE, Pretorius Holme M, Gaolathe T, Mmalane M, Kadima E, et al. Universal testing, expanded treatment, and incidence of HIV infection in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(3):230–42.

Bekele T, Rourke SB, Tucker R, Greene S, Sobota M, Koornstra J, et al. Direct and indirect effects of perceived social support on health-related quality of life in persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2013;25(3):337–46.

Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52(1):30–41.

Khamarko K, Myers JJ, Organization WH. The Influence of social support on the lives of HIV-infected individuals in low-and middle-income countries. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

Greeff M, Uys LR, Wantland D, Makoae L, Chirwa M, Dlamini P, et al. Perceived HIV stigma and life satisfaction among persons living with HIV infection in five African countries: a longitudinal study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(4):475–86.

Smith R, Rossetto K, Peterson BL. A meta-analysis of disclosure of one’s HIV-positive status, stigma and social support. AIDS Care. 2008;20(10):1266–75.

Haberlen SA, Nakigozi G, Gray RH, Brahmbhatt H, Ssekasanvu J, Serwadda D, et al. Antiretroviral therapy availability and HIV disclosure to spouse in Rakai, Uganda: a longitudinal population-based study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(2):241.

King R, Katuntu D, Lifshay J, Packel L, Batamwita R, Nakayiwa S, et al. Processes and outcomes of HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partners among people living with HIV in Uganda. AIDS Behav Mars. 2008;12(2):232–43.

Suzan-Monti M, Kouanfack C, Boyer S, Blanche J, Bonono R-C, Delaporte E, et al. Impact of HIV comprehensive care and treatment on serostatus disclosure among Cameroonian patients in rural district hospitals. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e55225.

Petrak JA, Doyle A-M, Smith A, Skinner C, Hedge B. Factors associated with self-disclosure of HIV serostatus to significant others. Br J Health Psychol. 2001;6(1):69–79.

Orne-Gliemann J, Larmarange J, Boyer S, Iwuji C, McGrath N, Bärnighausen T, et al. Addressing social issues in a universal HIV test and treat intervention trial (ANRS 12249 TasP) in South Africa: methods for appraisal. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):209.

Zaidi J, Grapsa E, Tanser F, Newell M-L, Bärnighausen T. Dramatic increases in HIV prevalence after scale-up of antiretroviral treatment: a longitudinal population-based HIV surveillance study in rural kwazulu-natal. AIDS Lond Engl. 2013;27(14):2301.

Hlabisa case book in HIV & TB medicine. Dr Tom Heller; 152 p.

Hlabisa Local Municipality—Demographic. [cité 28 févr 2019]. Disponible sur: https://municipalities.co.za/demographic/1092/hlabisa-local-municipality

National Department of Health, Republic of South Africa. The South African antiretroviral treatment guidelines. Pretoria: Department of Health, Republic of South Africa; 2013.

National Department of Health, Republic of South Africa. National consolidated guidelines for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) and the management of HIV in children, adolescents and adults. Pretoria: Department of Health, Republic of South Africa; 2015.

Iwuji CC, Orne-Gliemann J, Tanser F, Boyer S, Lessells RJ, Lert F, et al. Evaluation of the impact of immediate versus WHO recommendations-guided antiretroviral therapy initiation on HIV incidence: the ANRS 12249 TasP (Treatment as Prevention) trial in Hlabisa sub-district, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14(1):230.

Gultie T, Genet M, Sebsibie G. Disclosure of HIV-positive status to sexual partner and associated factors among ART users in Mekelle hospital. HIVAIDS Auckl N Z. 2015;7:209.

Kouanda S, Yaméogo WME, Berthé A, Bila B, Yaya FB, Somda A, et al. Partage de l’information sur le statut sérologique VIH positif: facteurs associés et conséquences pour les personnes vivant avec le VIH/sida au Burkina Faso. Rev DÉpidémiologie Santé Publique. 2012;60(3):221–8.

Fitzgerald M, Collumbien M, Hosegood V. “No one can ask me ‘Why do you take that stuff?’”: men’s experiences of antiretroviral treatment in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2010;22(3):355–60.

Pouvoir partager / Pouvoirs Partagés | Dévoilement. [cité 16 janv 2019]. Disponible sur: http://pouvoirpartager.uqam.ca/devoilement.html

Sow K. Partager l’information sur son statut sérologique VIH dans un contexte de polygamie au Sénégal: HIV disclosure in polygamous settings in Senegal. SAHARA-J J Soc Asp HIVAIDS. 2013;10(sup1):S28–36.

Miller GE, Cole SW. Social relationships and the progression of human immunodeficiency virus infection: a review of evidence and possible underlying mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 1998;20(3):181–9.

Kaplan RM, Patterson TL, Kerner D, Grant I. Social support: cause or consequence of poor health outcomes in men with HIV infection? In: Sarason BR, Sarason IG, Pierce GR, editors. Sourcebook of social support and personality. New York: Plenum Press; 1997. p. 279–301.

Iwuji CC, Orne-Gliemann J, Larmarange J, Okesola N, Tanser F, Thiebaut R, et al. Uptake of home-based HIV testing, linkage to care, and community attitudes about ART in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: descriptive results from the first phase of the ANRS 12249 TasP cluster-randomised trial. PLoS Med. 2016;13(8):e1002107.

Jean K, Niangoran S, Danel C, Moh R, Kouamé GM, Badjé A, et al. Early antiretroviral therapy initiation in west Africa has no adverse social consequences: a 24-month prospective study. AIDS Lond Engl. 2016;30(10):1677–82.

Rolland M, McGrath N, Tiendrebeogo T, Larmarange J, Pillay D, Dabis F, et al. No effect of test and treat on sexual behaviours at population level in rural South Africa. AIDS. 2019;33(4):709–22.

Iwuji C, McGrath N, Calmy A, Dabis F, Pillay D, Newell M-L, et al. Universal test and treat is not associated with sub-optimal antiretroviral therapy adherence in rural South Africa: the ANRS 12249 TasP trial. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21(6):e25112.

Obermeyer CM, Baijal P, Pegurri E. Facilitating HIV disclosure across diverse settings: a review. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(6):1011–23.

Loubiere S, Peretti-Watel P, Boyer S, Blanche J, Abega S-C, Spire B. HIV disclosure and unsafe sex among HIV-infected women in Cameroon: results from the ANRS-EVAL study. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(6):885–91.

Olley BO, Seedat S, Stein DJ. Self-disclosure of HIV serostatus in recently diagnosed patients with HIV in South Africa. Afr J Reprod Health. 2004;8:71–6.

Simbayi LC, Kalichman SC, Strebel A, Cloete A, Henda N, Mqeketo A. Disclosure of HIV status to sex partners and sexual risk behaviours among HIV-positive men and women, Cape Town, South Africa. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83(1):29–34.

Wong LH, Van Rooyen H, Modiba P, Richter L, Gray G, McIntyre JA, et al. Test and tell: correlates and consequences of testing and disclosure of HIV status in South Africa (HPTN 043 Project Accept). J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50(2):215.

Hodgson I, Plummer ML, Konopka SN, Colvin CJ, Jonas E, Albertini J, et al. A systematic review of individual and contextual factors affecting ART initiation, adherence, and retention for HIV-infected pregnant and postpartum women. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(11):e111421.

Skogmar S, Shakely D, Lans M, Danell J, Andersson R, Tshandu N, et al. Effect of antiretroviral treatment and counselling on disclosure of HIV-serostatus in Johannesburg. South Africa AIDS Care. 2006;18(7):725–30.

Skhosana NL, Struthers H, Gray GE, McIntyre JA. HIV disclosure and other factors that impact on adherence to antiretroviral therapy: the case of Soweto, South Africa. Afr J AIDS Res. 2006;5(1):17–26.

Lyimo RA, Stutterheim SE, Hospers HJ, de Glee T, van der Ven A, de Bruin M. Stigma, disclosure, coping, and medication adherence among people living with HIV/AIDS in Northern Tanzania. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2014;28(2):98–105.

Acknowledgements

Our sincere thanks to the PLHIV and workers who participated into the TasP trial. This study was funded by the ANRS (France Recherche Nord & Sud Sida-HIV Hépatites; ANRS 12324). We also thank Jude Sweeney for revising and editing the English version of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Baseline Characteristics Regarding HIV Disclosure for the Study Population on (n = 182) and for Participants Excluded Because Only One Measure of this Outcome was Available for the Whole Study Period (n = 290), ANRS 12,249 TasP trial

Covariates | Study population (n = 182) | Excluded participants (n = 290) | Total (n = 472) | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Sociodemographic and economic characteristics | ||||

Female gender, n (%) | 152(84%) | 240 (83%) | 392 (83%) | 0.831 |

Age (in years), median [IQR]* | 32 [25–48] | 30 [24–44] | 31 [25–45] | 0.155 |

Having a regular partner, n (%) | ||||

Yes | 144 (79%) | 235 (81%) | 379 (80%) | 0.611 |

HIV prevalence in the geographical cluster of residence, n (%) | ||||

≥ 30% | 150 (82%) | 211 (73%) | 361 (77%) | 0.016 |

Educational level#, n (%) | 0.162 | |||

Primary or less | 84 (46%) | 117 (41%) | 201 (43%) | |

Some secondary | 58 (32%) | 116 (41%) | 174 (37%) | |

At least completed secondary | 40 (22%) | 53 (19%) | 93 (20%) | |

Employment status§, n (%) | 0.788 | |||

Employed | 21 (12%) | 38 (13%) | 59 (13%) | |

Student | 14 (8%) | 19 (7%) | 33 (7%) | |

Inactive | 146 (81%) | 224 (80%) | 370 (80%) | |

Clinical characteristics | ||||

Having received HIV care in government clinics (currently or previously), n (%) | ||||

Yes | 94 (52%) | 105 (35%) | 199 (42%) | 0.001 |

Newly diagnosed, n (%) | ||||

Yes | 14 (8%) | 56 (19%) | 70 (15%) | 0.001 |

CD4 cell count/mm3, median [IQR] | 660 [568–816] | 665 [569–801] | 662 [569–807] | 0.566 |

Time to linkage to a trial clinic after referral, n (%) | 0 | |||

0–1 month | 111 (61%) | 143 (49%) | 254 (54%) | |

1–6 months | 47 (26%) | 51 (18%) | 98 (21%) | |

More than 6 months | 24 (13%) | 96 (33%) | 120 (25%) | |

HIV disclosure score, median [IQR] | 0.915 |

Appendix 2: Baseline Characteristics Regarding Social Support for the Study Population (n = 152) and of for Participants Excluded Because Only One Measure for This Outcome was Available for the Whole Study Period (n = 320), ANRS 12,249 TasP trial

Study population (n = 152) | Excluded participants (n = 320) | Total (n = 472) | P-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Sociodemographic and economic characteristics | ||||

Female gender, n (%) | 128 (84%) | 264 (83%) | 392 (83%) | 0.643 |

Age (in years), median [IQR]* | 32 [25–48] | 30 [24–44] | 31 [25–45] | 0.34 |

Having a regular partner, n (%) | ||||

Yes | 120 (79%) | 259 (81%) | 379 (80%) | 0.612 |

HIV prevalence in the geographical cluster of residence, n (%) | ||||

≥ 30% | 124 (82%) | 237 (74%) | 362 (77%) | 0.072 |

Educational level#, n (%) | 0.211 | |||

Primary or less | 70 (46%) | 131 (41%) | 201 (43%) | |

Some secondary | 48 (32%) | 126 (40%) | 174 (37%) | |

At least completed secondary | 34 (22%) | 59 (19%) | 93 (20%) | |

Employment status$, n (%) | 0.343 | |||

Employed | 15 (10%) | 44 (14%) | 59 (13%) | |

Student | 13 (9%) | 20 (6%) | 33 (7%) | |

Inactive | 123 (81%) | 247 (80%) | 371 (80%) | |

Clinical characteristics | ||||

Having received HIV care in government clinics (currently or previously), n (%) | ||||

Yes | 74 (49%) | 125 (39%) | 199 (42%) | 0.048 |

Newly diagnosed at referral, n (%) | ||||

Yes | 14 (9%) | 56 (18%) | 70 (15%) | 0.018 |

CD4 cell count/mm3, median [IQR] | 661 [572–824] | 663 [569–796] | 662 [569–807] | 0.938 |

Time to linkage to a trial clinic after referral, n (%) | 0 | |||

0–1 month | 94 (62%) | 160 (50%) | 254 (54%) | |

1–6 months | 38 (25%) | 60 (19%) | 98 (21%) | |

More than 6 months | 20 (13%) | 100 (31%) | 120 (25%) | |

Social support score, median [IQR] | 1 [1–2.5] | 1 [0–2] | 1 [1–2] | 0.265 |

Appendix 3: Characteristics of the Study Population Regarding the Outcome Social Support (n = 152), ANRS 12,249 TasP trial

Control (n = 75) | Intervention (n = 77) | Total (n = 152) | P-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Sociodemographic and economic characteristics at baseline (i.e. first clinic visit) | ||||

Female gender, n (%) | 63 (84%) | 65 (84%) | 128 (84%) | 0.944 |

Age (in years), median [IQR] | 32 [24–48] | 32 [25–47] | 32 [25–48] | 0.535 |

Having a regular partner, n (%) | ||||

Yes | 56 (75%) | 64 (83%) | 120 (79%) | 0.201 |

HIV prevalence in the geographical cluster of residence, n (%) | 0.004 | |||

≥ 30% | 68 (91%) | 56 (73%) | 124 (82%) | |

Educational level, n (%) | 0.556 | |||

Primary or less | 36 (48%) | 34 (44%) | 70 (46%) | |

Some secondary | 25 (33%) | 23 (30%) | 48 (32%) | |

At least completed secondary | 14 (19%) | 20 (26%) | 34 (22%) | |

Employment status$, n (%) | 0.379 | |||

Employed | 8 (11%) | 7 (9%) | 15 (10%) | |

Student | 4 (5%) | 9 (12%) | 13 (9%) | |

Inactive | 62 (84%) | 61 (79%) | 123 (81%) | |

Clinical characteristics | ||||

Having received HIV care in government clinics (currently or previously), n (%) | ||||

Yes | 41 (55%) | 33 (43%) | 74 (49%) | 0.145 |

Newly diagnosed at referral, n(%) | 7 (9%) | 7 (9%) | 14 (9%) | 0.959 |

Yes | ||||

CD4 cell count/mm3at baseline, median [IQR] | 687 [581–840] | 655 [551–815] | 661 [572–824] | 0.49 |

Time to linkage to a trial clinic after referral, n (%) | 0.851 | |||

0–1 month | 46 (61%) | 48 (62%) | 94 (62%) | |

1–6 months | 20 (27%) | 18 (23%) | 38 (25%) | |

More than 6 months | 9 (12%) | 11 (14%) | 20 (13%) | |

Time since baseline (in years), median [IQR] | 13.9 [7.3–19.8] | 15.1 [8.3–19.8] | 14.1 [7.8–19.8] | 0.804 |

Followed for at least 6 months, n(%) | 75 (100%) | 77 (100%) | 152 (100%) | |

Followed for at least 12 months, n(%) | 49 (65%) | 50 (65%) | 99 (65%) | 0.959 |

Followed for at least 18 months, n(%) | 27 (36%) | 32 (42%) | 59 (39%) | 0.482 |

Followed for at least 24 months, n(%) | 11 (15%) | 9 (12%) | 20 (13%) | 0.587 |

Having initiated ART in a trial clinic after baseline, n (%) | ||||

At the 6 month-visit | 9 (20%) | 62 (98%) | 71 (66%) | 0 |

At the 12 month-visit | 12 (31%) | 40 (98%) | 52 (65%) | 0 |

At the 18 month-visit | 13 (59%) | 31 (97%) | 44 (81%) | 0.001 |

At the 24 month-visit | 9 (82%) | 9 (100%) | 18 (90%) | 0.479 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fiorentino, M., Nishimwe, M., Protopopescu, C. et al. Early ART Initiation Improves HIV Status Disclosure and Social Support in People Living with HIV, Linked to Care Within a Universal Test and Treat Program in Rural South Africa (ANRS 12249 TasP Trial). AIDS Behav 25, 1306–1322 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03101-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03101-y