Abstract

There are few studies of HIV risk behavior among men who have sex with men (MSM) in sub-Saharan Africa. We conducted a behavioral survey of MSM in peri-urban “township” communities in Gauteng province, South Africa. Between October 2004 and March 2005, 199 MSM completed an interviewer administered pen-and-paper standardized questionnaire. The sample was 94% black, 83% identified as gay, and 12% as bisexual. Among those reporting sex with other men in the prior six months (n = 147), 59% reported unprotected anal intercourse (UAI). Increased risk of UAI was associated with both regular drinking (adjusted odds ratio (OR) 4.1, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.4, 12.6) regular drinking to intoxication (OR 2.6, 95% CI 1.0, 6.8), and reporting symptoms of rectal trauma resulting from anal intercourse (AI; OR 4.3, 95% CI 1.8, 10.4). Decreased risk of UAI was associated with the exclusive use of lubricants that are latex-compatible for AI (OR 0.3, 95% CI 0.1, 0.7). Township MSM in South Africa are at high risk of HIV infection. Targeted sexual health and risk reduction interventions that address the link between alcohol use and HIV risk are urgently needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The magnitude of the heterosexual HIV epidemic in most of sub-Saharan Africa and the general social stigma attached to homosexual behavior have presented challenges to understanding HIV risk behavior among men who have sex with men (MSM). Early studies of MSM in sub-Saharan Africa focused on sexuality and risk behavior in institutionalized settings, such as among prison inmates or all-male migrant labor compounds. (Goyer and Gow 2001; Niehaus 2002; Odujinrin and Adebajo 2001; Zachariah et al. 2002). Recently published studies and reports from Senegal (Niang et al. 2002; Teunis 2001; Wade et al. 2005) Kenya (Onyango-Ouma et al. 2005), and Uganda (Kajubi et al. 2007) have explored male homosexual identities, behaviors, and HIV risk in urban community settings.

It is perhaps surprising that in South Africa, the only African nation with legal guarantees of equal rights for gay and lesbian citizens and highly visible gay and lesbian communities, little attention has been paid to the HIV epidemic among MSM by either the research or health services communities. Since the end of the apartheid regime in 1994, there have been a number of cultural studies of urban gay Black communities, (Donham 1998; Graziano 2004; McLean and Ngcobo 1995; Spruill 2004) but none explicitly addresses the HIV epidemic. Neither are MSM a primary focus of national or local HIV prevention efforts sponsored by government or private health service organizations. Surveillance of HIV among urban MSM populations has not taken place since 1986. Although lesbian-gay-bisexual-transgender (LGBT) community-based organizations (CBOs) in South Africa’s urban centers have undertaken HIV education and condom distribution programs among gay men, to date there have been no published research findings on sexual risk behaviors of South African MSM.

Alcohol is the most commonly consumed and abused drug in South Africa (Parry 1998; Parry et al. 2002). An emerging body of research on alcohol and HIV in sub-Saharan Africa has found that alcohol consumption is related to sexual risk behavior (Kalichman et al. 2007), HIV seropositivity (Fritz et al. 2002; Lewis et al. 2005; Mbulaiteye et al. 2000), and HIV seroconversion (Fritz et al. 2002; Zablotska et al. 2006). To date, studies that have explored the relationship between alcohol consumption and HIV in the region have focused only on heterosexual transmission, with the exception of one study of MSM in Senegal (Wade et al. 2005), which did not find a significant association between alcohol and HIV infection. There is an extensive literature on non-injection drug use and HIV risk behavior in MSM populations elsewhere in the world. Many studies have found associations between sexual risk behavior and consumption of recreational drugs including crystal methamphetamine, ecstasy, cocaine, gamma hydroxybutyrate (GHB), and amyl nitrate (“poppers”) in a variety of social contexts (Choi et al. 2005; Colfax et al. 2001; Darrow et al. 2005; Hirshfield et al. 2004; Koblin et al. 2006; Operario et al. 2006; Rawstorne et al. 2007; Spindler et al. 2007; Stueve et al. 2002). One study has described sexual risk behavior among members of drug-using sub-populations of urban South African MSM (Parry et al. 2008). To date, there are no published findings on associations between non-injection drug use and sexual risk behavior for HIV infection in an MSM population in sub-Saharan Africa.

In this paper, we present the results of the Gauteng MSM Study, a survey of sexual risk behaviors and attitudes towards HIV testing among MSM in low-income peri-urban “township” communities in Gauteng Province, South Africa. Gauteng is a geographically small but densely populated, urbanized province of 8.8 million, containing South Africa’s economic capital, Johannesburg, and its political capital, Tshwane (formerly Pretoria). “Townships” refer to communities on the outskirts of urban centers that were designated as the only legal residential areas for urban black South Africans under apartheid. In the post-apartheid era, townships continue to be characterized by higher population density and lower per capita income levels than more affluent suburban communities. Prior to commencing this study, we met with members of a local lesbian-gay-bisexual-transgender (LGBT) community-based organization (CBO) active among township MSM to discuss the aims of this project. In particular, we sought guidance from CBO members on local sexual identity categories, patterns of substance use and sexual activity, and MSM social venues.

Our results include descriptive statistics on MSM sexual identities and behaviors, including condom and lubricant use, alcohol and drug consumption, and predictors of unprotected anal intercourse. We discuss the implications of our findings for future behavioral, epidemiological, and intervention research with this population.

Methods

Participants

The study employed both chain-referral and venue-based recruitment among MSM in low-income township communities around Gauteng province (including Soweto, Mamelodi, Atteridgeville, and Soshanguve). Men were eligible to participate in the study if they were over the age of 18 and had ever had manual, oral, or anal sex with another man.

Participants were initially approached by four male peer outreach workers familiar with the township communities through community gatekeepers or through contacts at venues where gay men and other MSM were known to socialize. These venues included the field offices of an LGBT CBO; religious organizations; bars, taverns, and nightclubs; and private social gatherings in the homes of gay-identified community members. Outreach workers explained the purpose of the study to potential participants, and provided them with study information leaflets and a phone number to call to arrange an interview appointment for another time. In addition, MSM who were approached by outreach workers were encouraged to share information with other MSM whom they knew who were not in attendance at these venues when outreach workers were present. Appointments were scheduled within 2 weeks of recruitment.

Measures

The survey instrument was adapted from a survey for MSM that has been used in other developing country settings (Family Health International 2000). Each pen-and-paper survey interview was administered by one of two trained interviewers (one man and one woman) in the participant’s choice of Zulu, Sotho, or English. The interview covered topics including demographic characteristics, sexual identity, numbers and types of sexual partners, group sexual encounters, sexual coercion, condom and lubricant use, alcohol and drug use, and questions about sexual health, including self-reports of symptoms of rectal trauma associated with anal intercourse (AI), symptoms of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and history of HIV testing. Interviews lasted approximately 45 min. Interviewers obtained verbal informed consent from each participant prior to the interview. The study was approved by the Committee on Human Research Ethics at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, and the Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco.

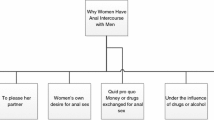

The survey offered sexual identification categories of “gay,” “bisexual,” “straight,” and “other” based on qualitative fieldwork with this population prior to the survey. For purposes of analysis, we collapsed these into two categories: gay/other, and bisexual/straight. Sexual coercion was measured by an affirmative response to the question “Has any man ever forced you to have sex with him, even though you did not want to have sex at that time, or with him in particular?” To assess public sexual activity, participants were asked if they have ever had sex in a public place, a sex-on-premises venue, or in a group of three or more persons. To assess unprotected AI (UAI) with other men, participants were asked the number of times they had engaged in insertive or receptive AI, how many times they had used condoms for these acts (consistency of condom use), and whether condoms had slipped, torn, or broken during AI (condom failure). For purposes of analysis, men were considered to have engaged in UAI if they reported either inconsistent condom use or condom failure during AI. To assess lubricant use, participants were asked whether they used lubrication for AI, and then asked to name the specific products they used for lubrication. For purposes of analysis, we defined lubricant use as “always latex compatible” if men who reported lubricant use did not report using some form of oil-based lubrication.

To assess alcohol use, participants were asked to characterize their own use of alcohol through two questions: “During the last 4 weeks, how often have you had drinks containing alcohol?” and “How often would you say you were drunk?” For the purpose of analysis, answers were collapsed into three categories: those who drank alcohol less than once per week and were drunk less than once per week (“irregular drinkers”); those who drank alcohol once per week or more, and were drunk less than once per week (“regular drinkers”); and those who drank alcohol once per week or more, and were drunk once per week or more (“regular drinkers to intoxication”). The category of “irregular drinkers” included men who reported no alcohol use in the last month. Drug use was measured by asking whether participants had ever used specific illicit drugs that are known to be used in the general population in South Africa (including cocaine, heroin, marijuana, methaqualone, and methcathinone), as well as those commonly used in other MSM populations in the world (amyl nitrate (“poppers”), crystal methamphetamine, and ecstasy). Participants were also asked if they had ever injected any illicit drug.

Questions related to sexual health included self-assessments of AI-associated rectal trauma and history of STIs. To assess rectal trauma, participants were asked if they had ever experienced hemorrhoids (“piles”), fissures (“anal cracks or tears”), or bleeding from the anus after AI with another man. To assess history of STIs, men were asked whether they had experienced genital or anal ulcers or sores within the prior 12 months. To assess HIV testing history, men were asked whether they had ever tested for HIV. Men who had tested were asked how long ago they had tested, and if they would disclose the result of that test to the interviewer.

Data Analysis

We explored associations between demographic, sexual identity, sexual health and HIV testing variables across categories of UAI and alcohol use using χ2 tests. We then conducted bivariate logistic regression analyses to explore relationships between demographic, sexual identity, alcohol use, sexual activity, sexual health, and HIV testing predictors and an outcome of any reported UAI among MSM who were sexually active during the previous six months. A multivariate model of predictors of UAI was constructed using variables associated with UAI in bivariate analysis at P < 0.20 to conserve statistical power. Data were analyzed using Stata 9.0.

Results

Between October 2004 and March 2005, 202 men contacted study staff to arrange interviews. Two men under the ase of 18 were excluded during screening. Of the 200 men who consented to a study interview, one had never had sex with men and his interview was terminated. Responses from 199 men are included in this analysis as the full sample. Each of South Africa’s 11 major linguistic and ethnic groups were represented in the sample: 26% of participants spoke Zulu at home, 23% Tswana, 19% Northern Sotho, 10% Southern Sotho; fewer than 10% spoke Tsonga, Xhosa, Ndebele, Swazi, Afrikaans, Venda, or English. Ninety-four percent of the participants were Black, 4% were Afrikaans-speaking Coloured (South Africans of mixed racial ancestry), and 2% were White. All but one participant were native to South Africa.

Eighty-three percent of MSM in the full sample self-identified as “gay”, 12% as “bisexual”, 1% as “straight,” and 4% as “other”. (Men who chose “other” described identities that, like “gay”, are generally associated with feminine gender identity (Donham 1998; McLean and Ngcobo 1995), and so were included with self-identified gay men in the analysis.) The proportion of bisexually-identified men was less than the proportion who reported ever having had sex with a woman (25%), but greater than the proportion reporting a current female partner (4%). AI with other men was reported by 68%, while 6% reported oral sex only. It is important to note that in this sample, gay identity was correlated with exclusive practice of receptive AI (r = 0.40), and bisexual identity with exclusive practice of insertive AI (r = 0.90).

Alcohol was by far the most commonly used drug (78%) in the full sample, with marijuana a distant second (29%). Use of methaqualone (mandrax or “mama”) and heroin, which are known to be used in some lower-income communities in South Africa, were reported by 3% and 2% respectively. “Club drugs” popular among MSM in more affluent societies in the world, including cocaine crystal methamphetamine, ecstasy, GHB, and methcathinone (a popular “club drug” in South Africa, known locally as “khat” or “cat”), were not popular in this sample, having ever been used by less than 5% of participants.

Products that MSM reported using for lubrication during AI included KY-brand jelly as well as common household items such as unflavored yogurt, Vaseline-brand petroleum jelly, locally available oil-based skin moisturizers, and cooking oils. Most MSM who were sexually active in the last six months reported using latex-compatible lubrication (KY and/or yogurt) exclusively, but 35% of the full sample reported using some form of oil-based lubrication. Public sexual activity with other men was reported by 36%. A majority of participants (60%) reported some form of rectal trauma (hemorrhoids, fissure, or bleeding) that they attributed to receptive AI, and 15% reported having either genital or rectal STI symptoms within the last year. Although most men reported having ever tested for HIV, only 27% reported testing within the prior 6 months, and 38% had never tested. Forty-five percent had experienced sexual coercion by other men, with 20% reporting that this had taken place within the last 6 months.

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of 147 men reporting sex with male partners in the prior 6 months. Fifty-nine percent reported some form of UAI, either through inconsistent condom use or condom failure during AI. UAI was significantly more common among those who reported three or more partners, regular drinking to intoxication, experiencing sexual coercion by other men, symptoms of rectal trauma, and symptoms of STIs in the last 12 months. UAI was significantly less common among those who reported ever having female partners, having only 1 male partner in the last 6 months, and exclusive use of latex-compatible lubrication.

We also characterized sexually active men by levels of alcohol use. These results are reported in Table 2. In general, the proportion of men reporting behaviors that might place them at increased risk for HIV infection also increased with alcohol use. Compared to infrequent drinkers, the two groups of regular drinkers were more likely to report multiple partnerships, sex in a public venue, experiences of coerced sex with other men, symptoms of rectal trauma associated with AI, and STI symptoms. Among regular drinkers and among those who drank regularly to intoxication, the proportion of men reporting three partners in the prior 6 months was substantially greater than those reporting two partners.

To determine the relationship between alcohol, other HIV risk factors and UAI we explored bivariate relationships between demographic, behavioral, sexual health, and HIV testing variables. These results are summarized in Table 3. In bivariate analysis, men who drank regularly were at significantly greater risk of engaging in UAI than men who were infrequent drinkers. Among regular drinkers, men who drank regularly without being intoxicated at higher risk than those who drank to intoxication. Other variables significantly associated with greater risk of UAI in included having three or more partners in the previous 6 months, reporting rectal trauma or STI symptoms within the last 12 months, and reporting ever having been coerced into sex with another man. Ever having had a female partner, having had only 1 male sex partner in the prior 6 months, and exclusive use of latex-compatible lubrication were significantly associated with decreased risk of engaging in UAI.

In multivariate logistic regression analysis, use of alcohol and aspects of men’s sexual behavior remained significantly associated with UAI. Compared to men who drank less than once per week, men who were regular drinkers were four times more likely to report UAI (χ2 = 2.50, P < 0.05), while men who were regular drinkers and drank to intoxication at least once per week were over two times more likely to report UAI (χ2 = 1.97, P < 0.05). With respect to men’s sexual behavior, men who reported rectal trauma during sex where over four times more likely to report UAI (χ2 = 3.2, P < 0.01), while men who reported using latex-compatible lubrication were three times less likely to report UAI compared to other sexually active men (χ2 = −2.6, P < 0.05.).

Discussion

High risk for HIV infection through UAI was found among the MSM in our study, and alcohol use was a strong predictor of this risk. This is consistent with findings from studies in other sub-Saharan African contexts where alcohol consumption was associated with unprotected sexual intercourse (Fritzet al. 2002; Kalichman et al. 2007; Mataure et al. 2002; Morojele et al. 2006a, b; Weiser et al. 2006). In contrast to this literature, our data do not show a dose-response relationship between alcohol consumption and unprotected sex. It is possible in our sample that moderate alcohol use is a proxy for other behaviors in the drinking environment, i.e., that it reflects the social and sexual behavior of MSM who attend township bars and taverns on a weekly basis, but whose primary motivation to attend these venues is socializing with other MSM and meeting potential male sex partners, and not necessarily to consume alcohol. A more thorough knowledge of the relationship between alcohol consumption, the drinking environment, and sexual behavior will be an important part of applied HIV prevention research with this population. Morojele has suggested a model of alcohol use and sexual risk behavior between men and women in sub-Saharan Africa that considers the relationships between economic, peer-group, and interpersonal predictors and moderating factors such as drinking environments (Morojele et al. 2006b). This model is potentially useful to exploring these relationships among township MSM. Future behavioral research should include measures to assess the influence of peer groups and drinking environments on UAI among MSM in township settings.

That alcohol and marijuana were the most commonly used substances reflects the low-income level of the MSM communities studied. Alcohol—particularly commercially brewed beer—and marijuana are both relatively inexpensive and easily accessible in peri-urban townships, whereas the higher cost of “club drugs” place them well beyond the reach of most township MSM. In addition, it is important to note that the increased use of crystal methamphetamine that has been observed in other low-income settings in South Africa (Bateman 2006; Morris and Parry 2006; Parry et al. 2004) was not evident among township MSM in Gauteng at the time of this survey. Nonetheless, HIV prevention interventions for this population should be mindful of the potential for high-risk sexual behavior associated with crystal methamphetamine to increase suddenly and rapidly.

Although much sex between men is consensual, the proportion of men in the total sample reporting a history of sexual coercion by other men—45%—is striking, and is consistent with findings from MSM studies elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa (Onyango-Ouma et al. 2005; Wade et al. 2005). Sexual coercion between men must be further investigated for its role both as an immediate risk factor for HIV infection in MSM, as well as for the psychological consequences of sexual victimization that have been shown to contribute to high-risk sexual behaviors throughout their lives. (Jinich et al. 1998; Paul et al. 2001) Jewkes et al. found a strong relationship between reported same-sex sexual coercion and HIV seropositivity in a sample of young, rural South African men (Jewkes et al. 2006). It is unlikely that coerced sexual encounters between men take place with condoms or sufficient lubrication. That alcohol use was associated with sexual coercion in bivariate analysis in our sample suggests the need to further explore the relationship between alcohol, drinking environments, and coerced sexual encounters between men through additional qualitative and survey research.

The association we observed between reported post-AI rectal trauma and UAI in this sample remained strong even after controlling for levels of alcohol consumption and coerced sex. This relationship is obviously not causal, but it does suggest that even in consensual encounters, receptive partners may not be able to stop AI once it has begun despite pain, discomfort, or condom failure. It also suggests that men may not use adequate lubrication for AI whether they use condoms or not. Further research with this population should explore power dynamics between men in sexual encounters that may contribute to HIV transmission risk.

Our finding that “gay” self-identification was common stands in contrast to other studies of MSM in sub-Saharan Africa (Onyango-Ouma et al. 2005; Wade et al. 2005). However, the existence of “bisexual” and “straight” MSM identities, and the correlation between sexual self-identification and sexual positioning for AI suggests expressions of MSM sexualities that may be particular to the township social context. It also points to potential challenges in addressing the diverse HIV prevention needs of township MSM through outreach to a “gay community”. The specific meanings of township MSM identities, and their implications for HIV prevention, need to be explored more fully.

This study’s findings on the use of latex-compatible lubrication for AI has a number of important implications. The protective effect we observed in this data may reflect the fact that properly lubricated condoms are less likely to fail during AI, but it may also be a proxy for exposure to community-based or Internet-based HIV prevention efforts that target gay-identified MSM. One local LGBT CBO is active in distributing small packets of condoms, latex-compatible lubricant, and pamphlets printed in English and local languages at township MSM venues and events that explain what lubricants may be safely used with condoms. In addition, those with Internet access may seek out this information on local and international gay-oriented websites. However, although water-based lubricants are widely available at pharmacies and adult-oriented shops, they are relatively expensive compared to the cost of common, oil-based household products that provide lubrication. Our results suggest that condom distribution for township MSM would be more effective if accompanied by education about latex-compatible lubrication, and should ideally include distribution of these lubricants.

Our study has several limitations. Given that gay-identified men tend to be the most visible MSM, and the fact three of the four outreach workers were gay-identified men themselves, the convenience and chain-referral sampling methodology produced a sample that was heavily gay-identified. The proportions of sexual identities and risk behaviors claimed by men in this sample may not be representative of Gauteng’s township MSM population overall. Face-to-face pen-and-paper interviews may have contributed to underreporting of sensitive behaviors and experiences, including inconsistent condom use and coerced sexual encounters, so rates may be higher in actuality. Systematic underreporting of sensitive sexual behaviors to the female interviewer was not evident from the data, but cannot be ruled out entirely. These data suggest links to sexual risk behaviors of concern to South Africa’s generalized HIV epidemic, but these links remain to be established through a more representative sample of MSM. However, we do believe that the gay-identified men in this sample are likely to be representative of those township MSM at highest risk of HIV infection, and that the behaviors and experiences reported through this survey do establish that a significant amount of high-risk sex between men is taking place in peri-urban South African communities.

Overall, our findings show that township MSM pursue sexual encounters with each other in an environment laden with multiple overlapping risks. Furthermore, their specific HIV prevention needs have been largely overlooked by both public and private sector initiatives that have attempted to address these needs for youth, women, and men who engage in heterosexual relationships. It is clear from this preliminary exploration of HIV risk behavior among township MSM that alcohol consumption and drinking environments play an important role in HIV risk behavior in this population. Targeted sexual health promotion outreach to MSM who attend drinking establishments and referrals to non-stigmatizing health service providers are urgently needed. Future intervention research should explore whether drinking environments might serve as sites for targeted structural and behavioral interventions to encourage risk reduction among MSM.

References

Bateman, C. (2006). ‘Tik’ causing a health crisis. South African Medical Journal, 96(8), 672, 674.

Choi, K. H., Operario, D., et al. (2005). Substance use, substance choice, and unprotected anal intercourse among young Asian American and Pacific Islander men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention, 17(5), 418–429.

Colfax, G. N., Mansergh, G., et al. (2001). Drug use and sexual risk behavior among gay and bisexual men who attend circuit parties: A venue-based comparison. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 28(4), 373–379.

Darrow, W. W., Biersteker, S., et al. (2005). Risky sexual behaviors associated with recreational drug use among men who have sex with men in an international resort area: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Urban Health, 82(4), 601–609.

Donham, D. (1998). Freeing South Africa: The ‘Modernization’ of male-male sexuality in Soweto. Cultural Anthropology, 13(1), 3–21.

Family Health International. (2000). HIV/AIDS/STD behavioral surveillance survey for use with men who have sex with men.

Fritz, K., Woelk, G., et al. (2002). The association between alcohol use, sexual risk behavior and HIV infection among men attending beerhalls in Harare, Zimbabwe. AIDS and Behavior, 6(3), 221–228.

Goyer, K., & Gow, J. (2001). Transmission of HIV in South African prisoners: Risk variables. Society in Transition, 32(1), 128–132.

Graziano, K. J. (2004). Oppression and resiliency in a post-apartheid South Africa: Unheard voices of Black gay men and lesbians. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 10(3), 302–316.

Hirshfield, S., Remien, R. H., et al. (2004). Crystal methamphetamine use predicts incident STD infection among men who have sex with men recruited online: A nested case-control study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 6(4), e41.

Jewkes, R., Dunkle, K., et al. (2006). Factors associated with HIV sero-positivity in young, rural South African men. International Journal of Epidemiology, 35(6), 1455–1460.

Jinich, S., Paul, J., et al. (1998). Childhood sexual abuse and HIV risk-taking behavior among gay and bisexual men. AIDS and Behavior, 2(1), 41–51.

Kajubi, P., Kamya, M. R., et al. (2007). Gay and bisexual men in Kampala, Uganda. AIDS and Behavior. doi:10.1007/s10461-007-9323-7.

Kalichman, S. C., Simbayi, L. C., et al. (2007). Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: Systematic review of empirical findings. Prevention Science, 8, 141–151.

Koblin, B. A., Husnik, M. J., et al. (2006). Risk factors for HIV infection among men who have sex with men. AIDS, 20(5), 731–739.

Lewis, J. J., Garnett, G. P., et al. (2005). Beer halls as a focus for HIV prevention activities in rural Zimbabwe. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 32(6), 364–369.

Mataure, P., McFarland, W., et al. (2002). Alcohol use and high risk sexual behavior among adolescents and young adults in Harare, Zimbabwe. AIDS and Behavior, 6(3), 211–219.

Mbulaiteye, S. M., Ruberantwari, A., et al. (2000). Alcohol and HIV: A study among sexually active adults in rural southwest Uganda. International Journal of Epidemiology, 29(5), 911–915.

McLean, H., & Ngcobo, L. (1995). Abangibhamayo Bathi Ngimnandi (Those who fuck me say I’m tasty): Gay sexuality in reef townships. In M. Gevisser & E. Cameron (Eds.), Defiant desire: Gay and lesbian lives in South Africa (pp. 158–85). New York: Routledge.

Morojele, N. K., Brook, J. S., et al. (2006a). Perceptions of sexual risk behaviours and substance abuse among adolescents in South Africa: A qualitative investigation. AIDS Care, 18(3), 215–219.

Morojele, N. K., Kachieng’a, M. A., et al. (2006b). Alcohol use and sexual behaviour among risky drinkers and bar and shebeen patrons in Gauteng province, South Africa. Social Science & Medicine, 62(1), 217–227.

Morris, K., & Parry, C. (2006). South African methamphetamine boom could fuel further HIV. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 6(8), 471.

Niang, C., Diagne, M., et al. (2002). Meeting the sexual health needs of men who have sex with men in Senegal (pp. 1–3). New York: The Population Council, Inc.

Niehaus, I. (2002). Renegotiating Mascilinity in the South African Lowveld: Narratives of male-male sex in labour compounds and in prisons. African Studies, 61(1), 77–97.

Odujinrin, M. T., & Adebajo, S. B. (2001). Social characteristics, HIV/AIDS knowledge, preventive practices and risk factors elicitation among prisoners in Lagos, Nigeria. West African Journal of Medicine, 20(3), 191–198.

Onyango-Ouma, W., Birungi, H., et al. (2005). Understanding the HIV/STI risksand prevention needs of men who have sex with men in Nairobi, Kenya. Washington, DC: Population Council.

Operario, D., Choi, K. H., et al. (2006). Prevalence and correlates of substance use among young Asian Pacific Islander men who have sex with men. Prevention Science, 7(1), 19–29.

Parry, C. (1998). Substance abuse in South Africa: Country report focusing on young persons. Tygerberg, South Africa, Medical Research Council.

Parry, C. D., Bhana, A., et al. (2002). Alcohol use in South Africa: Findings from the South African Community Epidemiology Network on Drug use (SACENDU) Project. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 63(4), 430–435.

Parry, C. D., Myers, B., et al. (2004). Drug policy for methamphetamine use urgently needed. South African Medical Journal, 94(12), 964–965.

Parry, C., Petersen P., et al. (2008). Rapid assessment of drug-related HIV risk among men who have sex with men in three South African Cities. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 95(l–2), 45–53.

Paul, J. P., Catania, J., et al. (2001). Understanding childhood sexual abuse as a predictor of sexual risk-taking among men who have sex with men: The Urban Men’s Health Study. Child Abuse and Neglect, 25(4), 557–584.

Rawstorne, P., Digiusto, E., et al. (2007). Associations between crystal methamphetamine use and potentially unsafe sexual activity among gay men in Australia. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36, 648–654.

Spindler, H. H., Scheer, S., et al. (2007). Viagra, methamphetamine, and HIV risk: Results from a probability sample of MSM, San Francisco. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 34(8), 586–591.

Spruill, J. (2004). Ad/dressing the nation: Drag and authenticity in post-apartheid South Africa. Journal of Homosexuality, 46(3–4), 91–111.

Stueve, A., O’Donnell, L., et al. (2002). Being high and taking sexual risks: Findings from a multisite survey of urban young men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention, 14(6), 482–495.

Teunis, N. (2001). Same-sex sexuality in Africa: A case study from Senegal. AIDS and Behavior, 5(2), 173–182.

Wade, A. S., Kane, C. T., et al. (2005). HIV infection and sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men in Senegal. AIDS, 19(18), 2133–2140.

Weiser, S. D., Leiter, K., et al. (2006). A population-based study on alcohol and high-risk sexual behaviors in Botswana. PLoS Medicine, 3(10), e392.

Zablotska, I. B., Gray, R. H., et al. (2006). Alcohol use before sex and HIV acquisition: A longitudinal study in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS, 20(8), 1191–1196.

Zachariah, R., Harries, A. D., et al. (2002). Sexually transmitted infections among prison inmates in a rural district of Malawi. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 96(6), 617–619.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Center for AIDS Prevention Studies at the University of California, San Francisco, grant # P30 MH62246, funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). The authors are grateful for the support of staff and volunteers at the Perinatal HIV Research Unit, HIVSA, University of Pretoria’s Center for the Study of AIDS, OUT-Tshwane, and the gay communities of greater Johannesburg and Pretoria.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lane, T., Shade, S.B., McIntyre, J. et al. Alcohol and Sexual Risk Behavior Among Men Who Have Sex with Men in South African Township Communities. AIDS Behav 12 (Suppl 1), 78–85 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-008-9389-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-008-9389-x