Abstract

This study uses the Locke and Okali gender analysis framework to explore gender relations surrounding grain storage management and marketing in Binga District of Zimbabwe. The study was conducted during one grain storage season and involved multiple visits to selected households, which were used as case studies. The main question that the study sought to address was: “What bargaining goes on between men and women in the area of stored grain management and marketing?” Data were collected from four households, fitting into the following categories: simple monogamous, complex monogamous (two scenarios), and polygamous. Participatory rural appraisal tools and techniques were extensively used and formed the backdrop of all the data collection. The study established that much bargaining and strategizing occurs within the household in order for women to exercise control over the use of stored grain. The bargaining process was found to be a complex one of give-and-take without an immediately recognizable winner. There is evidence that women use this bargaining power to exert influence on their relative position in the household in terms of independent income generation and management, seniority, and overall household food security policies. While bargaining between and within gender remains shrouded in subtleness, individuals in a household consciously use their skills to manipulate the situation to their best advantage. This article is expected to initiate broader debate in the area of gender roles and bargaining in grain post-harvest management, an area often kept private by smallholder farmers in sub-Saharan Africa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

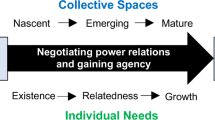

Gender is the socially determined division of roles, responsibilities, and power between men and women. These socially constructed roles are usually unequal in terms of power and decision making, as well as control over assets and events, and freedom of action and ownership of resources, among others (Ellis 2000). According to existing literature, rural household management decision making is male dominated (Hunter et al. 1990; Nabane 1994; Rocheleau 1995; Beneria and Bisnath 1996; Cleaver 2000; Chinyemba et al. 2006). For instance, in Southern Africa at least 50% of women are farmers yet the majority of these women are utilizing land to which they have no secure rights, hence they are not in a position to decide what crops to grow, when, and what resources to use (Beneria and Bisnath 1996). However, both men and women farmers play an important role in the household as decision makers in agro-biodiversity management (FAO 2005), although the value of women’s roles in agricultural production is often downplayed (Horwith 1989; Pankhurst 1991; Chinyemba et al. 2006). For instance, men and women jointly decide when to prepare their fields, plant, weed, harvest, process, store or market their crops. In addition, both genders decide how much of each crop variety to plant each year, how much seed to save from their own production and what to buy or exchange. This paper is based on the premise that women may not have decision-making power in a formal sense but may be heavily involved in the use of resources. If true, then women’s access to resources must be an outcome of background negotiations and positioning. In order for women to have access to resources, they must engage in some form of active or subtle negotiation within households and in society as a whole (Locke and Okali 2003). Women must also be adept at using these negotiations to maneuver within the existing constraints of gender relations in order for them to pursue and achieve their separate and joint interests.

Several gender frameworks for analyzing gender relations have been developed for planning, monitoring, and evaluating natural resources research aimed at improving the position of women within societies. A rapid assessment of gender frameworks shows that they have come a long way in identifying the separate interests of men and women as well as giving some indication of the shifts in the degree to which gender relations are equitable or empowering for women. However, improved understandings of gender point to the importance of the dynamic processes whereby gender relations are negotiated, maintained, and re-negotiated, and to the intrinsic ambiguity of changes in gender relations (Locke and Okali 2003). In general, existing gender frameworks focus on the changes in gender relations (i.e., whether the position of women has changed or improved as a result of project intervention) but do not address the process whereby these changes occur and cannot evaluate subtle outcomes. Although these frameworks give an insight into gender relations and are applicable to a wide range of situations and natural resources sectors, they fail to give a better understanding of the dynamics within gender relations—i.e., they are static. This apparent gap in understanding and analyzing gender relations gave rise to the development of an improved gender-monitoring framework (Locke and Okali 1999). The framework attempts to incorporate a more fundamental understanding of the relationships that exist between men and women. It seeks to penetrate deeper into gender analysis in order to understand how women use subtle strategies and covert negotiations in order to affect the process of changing existing gender relations. This is done firstly, by asking questions that get at the dynamic nature of gender relations, secondly, explicitly focusing on gender relations rather than simply cataloguing gender differences, and thirdly, developing understandings of the meaning of gender relations by looking at cultural and symbolic dimensions of gender and how they are invoked by specific actions in particular social situations.

A review of literature suggests that little attention has been paid to the hidden and underlying domains of decision making at the household level between and within genders. The main focus has largely been on public forms of participation in decision making yet informal arenas such as between husband and wife or between wives often play an important role in the process of negotiating resource access and decision making (Cleaver 2000; Nemarundwe 2003, 2005). It is imperative to analyze relationships between men and women at household level and especially with regard to post-harvest management of grain, as they influence household food security and may hinder participation in decision making at the same level. The current paper reports the activities and findings of a pilot gender study conducted under the Crop Post-Harvest Programme (CPHP) to collect gender-specific data using the Locke and Okali framework (1999). The CPHP was a collaborative research program through which extensive studies aimed at improving the crop post-harvest management systems in Zimbabwe have been conducted (Douglass et al. 1997; Stathers et al. 2000, 2005). Participatory rural appraisal (PRA) surveys were initially carried out to determine the post-harvest needs and constraints faced by farmers in Zimbabwe (Donaldson et al. 1997; Marange et al. 1997; Boyd et al. 1997). In Binga district, where the current study was conducted, two research projects (the HardwoodsFootnote 1 and the Inert DustsFootnote 2 projects) were already running. However, most of the surveys and research work clearly lacked a strong gender focus. It became apparent that although the agricultural research projects conducted within the smallholder farming sector were successful in terms of producing new technologies, there was a need for a clearer understanding of the gender relations (Lloyd-Laney 1997; Doss 2001). It was envisaged that by application of this framework, we could get a deeper understanding of gender relations around household level grain storage and marketing management, which would provide a basis for better project planning, monitoring, and evaluation. The current study focused on gender relations surrounding grain storage management, which is a post-harvest aspect, to enhance chances of uptake of research outputs by farmers. The specific objective of this study was to analyze gender relations in the crop post-harvest sub-sector in order to obtain an in-depth understanding of gender roles in grain storage management, using a gender-analysis framework recently developed by Locke and Okali (1999, 2003).

It is against this background that we identified three main questions for our study:

-

1.

What roles do men and women play in grain and store management and mid-season sales? We use this question to draw out differences between men and women in their perceptions and to provide a better understanding of the normative and actual roles of men and women in grain and store management.

-

2.

What are the strategies men and women use within households for grain and store management? Here we wanted to get a better understanding of household coping mechanisms with regard to food security based on differences in store management strategies.

-

3.

What bargaining goes on between men and women in the area of stored grain management and sales? The purpose of this question was to provide clarification on underlying factors affecting store ownership, management, and income generation. In addition, we wanted to gain a better understanding of gender difference in the generation and control of income from grain sales at the beginning of the storage season and during mid-season.

Our motivation is based in part on the fact that these questions have not previously been considered in both gender and post-harvest literature. Hence, our study of household grain storage management provides some important insights into the differences between and within households. Each research question was addressed separately but the resultant themes, ideas, and issues were extracted to develop indicative conclusions pertaining to gender relations surrounding grain post-harvest management. In addressing each question, the central analytical category needed to “sort” the data was identified and then a series of more specific questions were further identified for the respective category.

Methods

Site selection and study approach

The pilot gender study was conducted in Siabuwa Valley of Binga District located in Matebeleland North Province, Zimbabwe. Recognizing the complexity and sensitivity of analyzing gender relations at household level, the study strategically adopted a case study approach to ensure in-depth investigation and analysis. The approach was also adopted to penetrate the private and often secretive nature of household grain storage practices which makes understanding of grain storage issues particularly difficult, with quantities and qualities of grain stored neither readily disclosed by farmers nor obvious to others. Having a clearer understanding of the circumstances among rural households enhances the likelihood that solutions offered by projects better match needs and priorities of the target groups.

Case study households were selected from a pool of existing project farmers in order to build on the rapport already established between researchers and farmers and to ensure adequate dialog around potentially sensitive gender questions. Several factors were considered in site selection. First, there were already two CPHP research projects underway in Binga and on-going project activities in the area facilitated economic use of resources. Second, we were familiar with the target households and had a good rapport with them, which was essential in enabling more in-depth questions to be asked around sensitive issues. Third, researcher’s knowledge of the area also facilitated the gathering of the background information needed. Finally, polygamy is a common cultural practice within the Tonga tribe dominant in the area and this also gave scope for studying a variety of household types as well as giving an opportunity to gain more insight into the culture itself.

The study was conducted over a period of six months during the 1999–2000 storage season in which repeated visits were made to each household. Although the households also grew small grains (sorghum and pearl millet), the study mainly focused on the storage of maize, the main commercially traded grain, because in Zimbabwe this is regarded as men’s crop (Goebel 1999) and therefore provided more scope for exploring bargaining between men and women. Because the agronomic and post-production management (including storage) of small grains is usually the responsibility of women (Commutech 1997), the study allowed us to examine gender relations.

Data collection techniques

The PRA tools and techniques (Nabasa et al. 1995) formed the backdrop of all data collection. The flexible and informal nature of participatory techniques made it the most suitable methodology. Other researchers have found qualitative methods to be more appropriate than quantitative methods in collecting data on decision-making processes and institutional relationships (Nemarundwe 2005). A clearer understanding of the nuances surrounding men and women’s answers could be better explored because of the built-in flexibility of the approach compared to the more rigid structure of the formal questionnaire. One of the tools used was the semi-structured questionnaire. However, the order in which questions were asked around a theme varied from household to household as well as between and within genders. By the end of the study, all the questions had been explored and the information gathered was sufficient to enable us to compare and contrast between households.

Apart from the checklist-based semi-structured interviews, which were consistently used throughout the study, other PRA tools used included:

-

1.

Mapping—used mainly as an icebreaker and also to obtain information on store ownership.

-

2.

Ranking and scoring—used to give insight on the priorities men and women have with regard to grain use and management and the reasons behind them.

-

3.

Milk bottle technique—using a plastic milk bottle and sand, men and women were asked to demonstrate their perception of different levels of grain in the store during the storage season and the associated implications on decision making within a household. This was particularly important for complex and polygamous households.

These tools were used in both group and individual interviews. Multiple interviews were held with the households. One method that was adopted to understand the differences between gender perceptions and preferences better was to hold joint interviews with husband and wife/wives initially to get an overview of the household characteristics and general gender relations in post-harvest management of grain and then to ask similar but more detailed questions to the husband and wife/wives separately in subsequent visits. This categorization was undertaken because it was realized that some information about gender relations is highly dependent on the source and social context in which it is given (Williams et al. 1994). The reliability of information supplied depends on who is providing the information and who is present during the provision of the information (Locke and Okali 1999). Therefore, in cases where husband and wife were interviewed separately, a female researcher would interview the wife while a male researcher interviewed the husband. This was to avoid communication barriers due to cultural attitudes towards gender, both from the farmer’s perspective and subconsciously from our perspective. The gender combination of interviewer and respondent was an important consideration because the target community was of the Tonga tribe which still has strong cultural values.

Application of the Locke and Okali framework

The gender analysis framework used in this study involved a step-wise process (Okali et al. 2000):

(1) The assembly of background information: Background information on the household characteristics was collected such as household composition, income sources, and asset-base. This was mostly primary information gathered by project personnel (from the Hardwoods and the Inert Dusts projects within the CPHP) who had been working in the area for over two years. Semi-structured interviews were also conducted with the case study households to get more specific background information. This background information was necessary for us to understand the context of the study and to help in data interpretation.

(2) The identification of locally significant disaggregating variables: The purpose here was to identify the appropriate social units of generalization and to develop a method of disaggregation that is locally meaningful and useable. The background information made it simple to identify locally significant disaggregation variables given that the research team intended to use a small number of households as case studies. We disaggregated households using the type of marriage as the main variable as follows:

-

Simple monogamous household—household with a relatively young married couple.

-

Two complex monogamous households—household with a married couple living with mature individuals (sons, daughters, sons-in-law, daughters-in-law, relatives within the extended family) whose spouses may or may not be permanently resident in the same household.

-

Polygamous household—household with a husband married to more than one wife.

Four households fitting the outlined categories were identified as case studies to reflect the key household settings in the study site. Because of the demands associated with in-depth investigation which often required extended interviews, it was deemed strategic to deal with a more manageable number of cases. Detailed case studies are recognized as a suitable approach to qualitative enquiry amongst others (Locke and Okali 2003).

The two case studies in the complex monogamous category afore-mentioned reflect the different scenarios of complex monogamous households. One case highlights the relationship between a mother and daughter-in-law and the other case that between two sisters-in-law. It was assumed that bargaining would differ depending on the seniority and cultural expectations between the women in the households. All the four households had participated in both the Hardwoods and the Inert Dusts projects and the good rapport established between the farmers and project personnel was exploited.

(3) The framing of context-specific research questions: Context-specific questions refer to questions that were: related to local gender relations on particular issues; in a general sense surrounded store management and grain sales; and related to the way women and men strategize and bargain around these activities. These were developed through brain-storming sessions and designed to draw out the underlying reasons behind the strategizing and bargaining around grain storage management in relation to gender. These questions add to conventional gender frameworks by looking at the active strategies of women and men to optimize their joint and separate livelihood interests and security as well as the process of negotiation or bargaining between women and men.

(4) The recording of data on local gender relations: Researchers recorded all the responses to direct formal and informal questions and incidental comments, attitudes, and dissatisfaction communicated through body language, mannerisms, etc. Researchers’ good rapport with the households helped to provide a relaxed atmosphere.

(5) Examining changes in gender relations related to crop post-harvest activities: The gender relations surrounding grain storage, store management, and grain sales were the focus of the study. The methodology was designed to assist us in obtaining a nuanced sense of the incentives and power relations for men and women in grain storage management.

Results and discussion

Household profiles

A profile of each household case study, including an outline of the household’s set-up, storage structures, fields, and family composition, is summarized in Table 1; the qualitative aspects are detailed in the following subsections. In two of the households, the men own separate and larger pieces of land for cultivation compared to women. Studies reported by Commonwealth Secretariat (1996) as cited by Chinyemba et al. (2006) show that plots of land controlled by women have lower yields than those controlled by men and that these lower yields are usually the result of the use of less labor and fertilizers per unit area rather than inefficiency.

Case study 1: simple monogamous household

The household is composed of a relatively young couple with no children. The couple grows all their produce in the same field. The main crops grown are maize, sorghum, and cotton. The family has one storage structure and the wife is responsible for the day-to-day management of the stored grain. The husband determines the grain for bulk selling at the beginning of the storage season and does the actual selling of the grain but keeps the wife fully informed on the income generated. Together they then plan what to do with the money.

Case study 2: complex monogamous household

The husband (household head) and his wife have six children, two of whom are not permanent residents. They are also living with their daughter-in-law who has two young children. The son works at Binga Rural Service Centre and is not a permanent resident in the area. He remits some money to his wife and parents but this was highlighted as an insignificant amount. The household head and his wife grow the bulk of their produce in the main family fields, which belong to the household head. The wife owns a smaller field where she grows sorghum and maize with the help of casual laborers. The entire household contributes labor to the main family fields. The household head allocated the daughter-in-law a small portion of land near his main field on which she grows some grain which she can use for her own purposes. The piece of land, however, does not produce sufficient harvest to feed her for the whole season, therefore she depends mainly on the harvest from the main family field for survival.

The harvest from the main family field is divided into that for consumption and for bulk sales at the beginning of the storage season. The household head makes decisions on such grain allocation. All the grain is stored in polypropylene bags inside the main house (because the traditional store collapsed) with the husband, wife, and daughter-in-laws’ bags of grain being stored in the same room. Both the husband and the wife manage the stored grain as a joint enterprise. Grain from the wife’s field is stored in separate bags but is considered to be part of the total household harvest. However, the wife has more latitude in making marketing decisions around these bags as the season progresses. All sales are local, with the knowledge and consent of the husband, who often uses his information networks to advise his wife on the best marketing price.

The daughter-in-law needs to confer with her mother-in-law before she can sell grain from her portion of the field. This is primarily because the daughter-in-law relies on the overall family produce to survive. Furthermore, the mother-in-law may feel that it is better for the daughter-in-law to contribute her portion to maintain household food security. It was highlighted that the mother-in-law does not really have the final say and the daughter-in-law is free to dispose of the grain as she likes. In this household, one gets the impression that the husband is in full control of all the grain. Although he does not withdraw grain for consumption every day, he keeps a close eye on consumption rate and has the final say on the use and marketing of the grain.

Case study 3: complex monogamous household

The household consists of husband and wife with their six children plus the husband’s brother’s wife and her three young children in one homestead. The husband’s brother is not permanently resident in the household because he works in Binga Rural Service Centre. It is customary to find a man working in an urban area while his wife stays behind in the communal areas looking after the home and the children. The rationale is usually that men migrate when the expected returns from migration are higher than from on-farm production (Doss 2001). It is also because men need to maintain a rural home where they will retire and also because of the high cost of living together as a family in urban areas.

The household head acts as an overseer to his sister-in-law’s household affairs and keeps his brother informed. In this case study, the household head and his wife grow the same crops in a joint enterprise. The husband purchases seed and any other necessary inputs. The main crops grown are maize, sorghum, and cotton. The sister-in-law grows the same crops but in separate fields which belong to her husband. All members of the household (including the sister-in-law and her children) work together first on the household head’s fields and then on the sister-in-law’s fields on a rotational basis as a strategy to alleviate labor shortages between the two families. The same order is followed when harvesting the grains. The strategy of combining labor was of mutual benefit though the young brother’s family benefited more because their children were still too young for some of the agricultural tasks and also being a young family, they had a lower resource endowment in terms of draught animals and implements such as moldboard ploughs.

After drying and shelling or threshing, grain is stored in separate granaries. The household head and his wife store their maize grain in one large main store. The sorghum is stored separately but because it is not a major enterprise, relatively little sorghum is harvested compared to maize. The main store has three compartments. One compartment is loaded with maize grain for immediate consumption, i.e., consumption for the current season, the next compartment is loaded with maize grain for sale and the last one devoted to food security purposes. There are no bulk sales straight after harvesting because of the long distances that have to be travelled to reach the nearest Grain Marketing Board (GMB) depot, and also because Binga is such a drought prone area, farmers fear starvation. They generally only sell small quantities of grain at a time and to capitalize on local pan-seasonal price changes. The sister-in law stores her food separately in her own store and manages her own mid-season sales.

Case study 4: polygamous household

The husband is married to two wives, the first has five children and the second has three children. They live with the husband’s aged mother who makes little labor contribution to the household because of her advanced age. However, the mother stays in her own hut and is responsible for her own cooking but with access to food from the son. The husband and his wives grow crops in individual fields. Each wife actually owns a field although it is usually smaller than the husband’s field and each wife, together with her children, is responsible for her own field activities. The main crops grown are sorghum and maize. The husband purchases seed and any other inputs required for his field. Wives can do likewise for their own fields although they actually rarely purchase the inputs because of income limitations. Consequently, it is common for the women to grow more sorghum since it requires fewer inputs and seed can be retained from the previous season’s harvest, in contrast, to the maize hybrid seed used in the husband’s field, which needs to be bought at the beginning of each season. Both wives and children contribute labor to the husbands’ fields, and in fact, the husband’s fields have first priority. Wives only work in their own fields on days when they are not called upon to work on the husband’s fields. Each wife, with assistance from her children, is responsible for providing the labor required on her own field and it is unheard of for one wife to help the other with labor and/or inputs. The husband never contributes labor to the wives’ fields and does not provide them with seed or fertilizer.

Grain (maize and sorghum) from the husband’s field is harvested by all members of the family; after drying and threshing, it is stored in the husband’s store, which is used as the household strategic grain reserve for food security purposes. The wives do their own harvesting separately with help from their children or hired labor, and then store their food separately in individual granaries. Each wife is responsible for her own store and consumes grain from her store together with her children, on a day-to-day basis. The husband also consumes food from the wives’ granaries because every day, each wife cooks her own food and presents some of it to the husband who then eats an equal portion from each wife’s lot. In this culture, the husband usually takes his meals together with all male children present at home at that time, irrespective of whether they belong to the first or second wife. Once the grain in any of the wives’ store is depleted (usually by early to mid-September), the husband then begins to allocate grain from his store. The same measurement of grain is allocated to each wife even if one wife has more children than the other.

Management of the husband’s store is the responsibility of the junior wife. She is responsible for general maintenance of the store and the withdrawal of food at intervals prescribed by the husband. When asked whether the management role assigned to the junior wife was not based on favoritism, the husband pointed out that this was because the senior wife had “retired” from it and preferred to delegate the work. The husband sells some of the grain from his store in bulk immediately after harvest but leaves enough to sustain the family through to the next harvest. Mid-season sales from this store are determined by the husband although the wives can contest this decision to some degree, especially later on in the season when the grain levels were lower.

There are no bulk sales from the women’s stores after harvesting because the harvest from the women’s fields is usually relatively small. They have less time to work on their fields and as mentioned earlier, Binga is such a drought-prone area that the women tend to sell only small quantities at a time to remain food secure. The wives rely on mid-season sales to supplement their own needs. Beer brewing for local sale is the most important income-generating activity undertaken by the wives and they have full control over the income. Even if the husband asks one of the wives to brew beer on his behalf (for sale), the respective wife will demand some form of payment, be it the beer itself or some of the proceeds from the sales.

Discrimination of women in polygamous households have been reported and is based on seniority, with the first wife often being neglected as the husband seeks to please the younger wives (Chinyemba et al. 2006). The allocation of agricultural income when all women have jointly worked the land also creates conflict, which can result in accusations of witchcraft as the wives compete for the agricultural income.

Analysis of context-specific questions

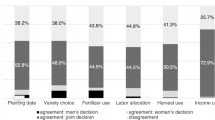

What roles do men and women have in store management and mid-season sales?

The central analytical category here is “gender role” and this requires examination of not just the roles of men versus women but also the roles of men and women in different positions in different households with respect to store ownership (Locke and Okali 1999). Details of these different roles between men and women and between women in a hierarchical setting are provided in Appendix 1. Table 2 outlines the normative roles of males and females in store construction and maintenance and grain management based on our observations and household interviews during study visits, and in accordance with the Locke and Okali framework. It is interesting to note that the separate interviews often exposed areas where the husband, in the joint interviews, gave answers based on what should happen and not on what actually happens. For example, the responses of husband in the polygamous household showed that he was not aware of the bargaining and delegation between the senior and junior wives in terms of maintaining stocks in his store. The husband in the complex monogamous household (Case study 2) overestimated the daughter-in-law’s ability to make decisions over mid-season sales since the mother-in-law (his wife) tended to exert pressure on the daughter-in-law for her to contribute to overall family food security, thus effectively limiting the mid-season sales.

While the gender roles in store management within all households adhere closely to the socio-cultural norms of the area, it was evident from the several interviews that some of the roles presented in Table 2 were not actually being practiced. For example, purchase and application of grain protectant were normally regarded as men’s responsibilities but none of the households either purchased or applied any grain protectant during the storage season under study. The Case study 2 household also did not have a traditional store because the store collapsed in the previous season and was not reconstructed. The husband fell ill for a long period and was unable to construct the store. However, the household finds it acceptable to store in bags and indicated that this storage method is more manageable in terms of grain monitoring and budgeting and store cleaning.

In a survey of grain store designs and storage practices in the Zambezi Valley which includes Binga district, Douglass et al. (1997) found that management of stored grain is the responsibility of women and men often showed distinct lack of interest when the issue of grain storage management was raised during focus group discussions. The same researchers reported that where a wife or wives and husband had separate stores, the wife or wives had the responsibility of managing the husband’s store. However, in cases where the husbands took the active role in storage management, the husband often gave instructions and the women implemented them. In concurrence with the current study, Douglass et al. (1997) also revealed that in cases of multiple stores identified with particular members of the household, it was always the women’s stores which were exhausted first.

Gender relations are dynamic and respond to economic incentives and opportunities (Doss 2001). However, the nature of the different activities within store management means that very few roles are negotiable although there can be some delegation of roles among women. For example, women may delegate their day-to-day roles such as general cleaning and even grain withdrawal to their children, giving themselves more time to perform other household duties. In Case study 4 the husband is responsible for the construction of all stores within his household (i.e., his own and for each of his wives). In that case, each wife undertakes the day-to-day management of their own store but in addition the junior wife performs the same management and daily maintenance duties for the husband’s store. The senior wife delegates the job of maintaining the husband’s store to the junior wife, perhaps as a way to reduce her own labor and also as a reflection of her more senior position. It may also be done on request by the husband.

In polygamous households, where there is joint interest in the husband’s store as the ultimate source of grain, the wives are constantly keeping an eye on each other to ensure that one wife does not favor her children over the children of another wife in terms of allocation of grain. As a result, the post-harvest roles between men and women and between the women are more defined and rigid, i.e., they stick to their respective normative roles as a means to control each other. Although the junior wife may have a greater contact with the husband’s store, the husband is actively involved in his store’s management and is aware of all grain withdrawals. Certainly, the senior wife also monitors the junior wife’s activities to ensure that she gets no advantage in terms of access to the grain.

In the monogamous households (Case Studies 1, 2, and 3) there is one household store and the husband and wife have the joint interest of household food security in managing the store. This joint interest has implications for the strategies employed by the wives within monogamous households in order to exercise some control over the use of stored grain and the income generated from both mid-season and bulk sales straight after harvest. It also has implications for the outcome of bargaining around the preferred use of grain (sale vs. consumption or barter for labor). Husbands and wives must co-operate with each other in order to secure household food security from the single shared store. In Case study 4, which is polygamous, the husband has the responsibility of ensuring overall household food security since each wife is only concerned with her own family unit. The shifts between conflict and co-operation between and within the different genders are more complex and subtle. Wives may co-operate with the husband and each other in order to arrive at appropriate levels of income from post harvest bulk sales but there are always undercurrents of conflict between wives as each one tries to maximize the food security of their family unit through access to the husband’s store later on in the season. There is a lesser degree of independence for women in monogamous marriages in terms of their individual or separate interests, whereas in the polygamous household, wives are more autonomous with respect to grain in their own stores. They can make their own decisions pertaining to sales and uses of the grain. In Case study 2, for example, the husband is actively involved in grain sales throughout the season, be they sales of grain from the wife’s field or from the main family fields. This means that the wife may not have as much latitude as the wives in the polygamous household in deciding when to sell and the quantities involved. She may also have less control over the income generated, although this could not be established with certainty.

In Case study 3, the husband consults his wife about levels of grain in the store before any sale but also directly checks for himself before making a sale. The legitimacy accorded by a husband to a wife’s advice not to sell grain as stocks get low is used as a bargaining tool. It would suggest that the balance of power in “negotiations” about grain sales swings towards wives as grain is depleted and that there is more room for husbands to contest earlier in the season. A similar trend is observed in the other households where women are able to halt mid-season sales because the stocks are low, indicating that concern for household food security results in more co-operation between husbands and wives. The household head in Case study 3 acts as an overseer to his sister-in-law’s affairs by advising her but does not make final decisions on store management for her store. This suggests that the degree of autonomy over the use of grain and self-reliance gained by the sister-in-law is increased because of the absence of her husband from the homestead. She is able to take on more of her husband’s roles in store management and this may be a useful tool for her when negotiating around other household concerns when her husband visits the homestead as she is the de facto head of the household.

The responsibility to supplement grain or goods for the household if stocks get exhausted rests with the husband, a common trend across all four households. This is an interesting finding because it is an area where the Tonga culture differs from that of the Shona, where most wives are the ones responsible. In the Shona culture the wife is generally responsible for feeding the family throughout the season and if grain levels become low, she goes out to offer her labor services in exchange for supplementary food (Matiza et al. 1988). The husband’s responsibility ends once the grain grown has been harvested and he expects the wife to manage the stored grain so that it will last until the next crop harvest. Shortage of grain is viewed as mismanagement resulting in the woman being considered a “bad” wife. There is considerably less pressure on women in Binga to portray themselves as “good” wives in this way and in fact a husband is considered to be a “bad provider” if grain stocks runs out mid-season.

Gender roles and responsibilities are known to be culturally specific and can change over time, sometimes being rapidly influenced by socio-economic and technological changes (Anonymous 2006). For example in analyzing women’s participation in project meetings, Sithole (2005) reported variable attendance depending on ethnicity. Some respondents mentioned culture as constraining women’s participation in meetings and cultural factors included “being traditional and respectful of cultural norms and values” which define roles and expectations of the two genders. The researcher’s interpretation of the cultural constraints included husbands’ tendency to forbid their wives from attending or participating at meetings; public disapproval of women who try to participate; or women who accept that they should not challenge the status quo. In the same study, the Shankwe women, who have close ethnic links with the neighboring Tonga women, were found to be less likely or willing to participate or attend public meetings than the Shona and the Ndebele when all the tribes occur in the same area.

Cultural beliefs also have a strong influence in crop processing in Zimbabwe. For example in the Tonga culture, traditional beer for rituals is only brewed by elderly post-menopausal women and young girls (Dzingai and Bourdillon 1998), a fact also confirmed in the current study during household interviews. In the Shona culture the same categories of females are involved in grain withdrawal and in initiating threshing of small grains because it is believed that if done by other people, the grain quantities would mysteriously diminish (personal observations). In the current study, women in the polygamous household reported that they brew beer but for local income generation purposes, even though they are still of child-bearing age.

In Kenya, Tobisson (1997) reported increased labor for loading and off-loading maize on the part of women, whose responsibility it is for crop handling and storage, when elevated maize drying and storage structures were introduced in the mid- to late-1980s. The women would have to solicit extra help from male family members not only because of the weight of the maize crop but also because of the need for the women to climb up the dryer using a ladder which is considered a taboo in particular communities in Kenya! In general, it appears that the interaction of culture, gender, and post-harvest operations is not well documented.

What are the strategies men and women use within households for store management?

The central analytical category here is “gender strategies.” These may be overt and/or covert negotiations employed to ensure household food security and improve women’s position in store management. Overt negotiations are those that are explicit and refer to actual negotiations—possibly verbal—that occur between gender groups. Covert negotiations are secret and hidden and refer to the subterfuge that women employ in negotiating with men and other women in the household. It was noted that every household had some kind of co-operative store management strategy that is supported by all individuals in the household. The strategies are different for each household depending on the varying contributions of the grown-up members present. The wife is the “family organizer” in all households and is responsible for the daily feeding of the household. In order to meet this obligation, the wife exercises tight management over the grain. She may, from time to time, draw on other enterprises such as vegetable production and working on other farmer’s fields in exchange for cash or other goods. These activities help the wife to supplement grain stocks on a small scale, procure relish or cash. The latter can be used for buying basic groceries, clothes or paying for grain milling fees. The husband is responsible for ensuring that grain is available for the household on a larger scale. An outline of the strategies for grain and store management employed by each household is presented in Table 3.

Household strategies are closely linked to gender roles and women work within the confines of these roles in order to address their individual needs. The husband controls the income from bulk sales at the beginning of the storage season as reported by both men and women in case studies 1–3. However, there is a lot more discussion and planning together in Case study 1. Generally, the control over the income from mid-season sales is more ambiguous. For example in Case study 3, while holding interviews for husband and wife, it became apparent that the money earned from these sales was kept locked in a metal trunk in the couple’s bedroom. The husband reported that both he and his wife kept the keys to the trunk and shared the money while the wife reported that she was in charge of the money gained from the sale of stored grain. She added that the husband had to make a request for money from her as she believed that she earned the money which should primarily be used for the up-keep of the homestead (i.e., buying her kitchenware) and meeting the needs of “her” children.Footnote 3 She indicated that she readily agrees with the husband when it comes to using the money for household goods such as groceries, children’s clothes, small farming implements, etc. However, she felt that if the husband wanted the money for his own uses (e.g., beer drinking and personal travel) he should sell one of his goats. We were unable to verify whether both the husband and his wife had keys to the trunk where the money from mid-season maize sales is kept.

This suggests that there is a lot of negotiation involved in the use of income generated through the mid-season sales. Women have a high interest in this income as it contributes to their self-reliance and supplements urgent household needs such as paying the grain milling fees and buying supplementary groceries. There maybe some kind of trade-off by women in letting husbands control the income from bulk sales. In interviews, husbands indicated that the money generated from mid-season grain sales is relatively insignificant, as one cannot purchase major items or agricultural inputs with it. However, it is apparent that women value this income and use it as a way of maintaining and supporting their individual interests both within and outside the household. It may be possible that the women actively and deliberately portray the income from these sales as insignificant in order to maintain more control over it. The advantages gained by women from mid-season sales would suggest that women might be keen to ensure that more grain than is needed for household consumption is stored. However, this desire is counter-balanced by the need for major household items such as a new plough, which may not be addressed if only a little amount of grain is sold after harvesting. Another reason why women keep an eye on finances is to thwart the husband’s “misuse” of the money in marrying another wife, a common practice in the community that could greatly disadvantage the incumbent wife and “her” children.

None of the households use grain protectants to prevent insect damage and this has a bearing on the feasibility of sales over the course of the season since grain quality deteriorates markedly. The use of grain protectants in the stores of the polygamous household, for example, may result in more grain stored in both the wives’ stores than that of their husband. The resulting undamaged grain will give the wives increased food security and higher income from the sale of quality grain during the storage season.

In the polygamous household (Case study 4), the wives indicated that although they have latitude in using their own grain, they also have an interest in the grain in the husband’s store. It therefore suggests that they would like more access to the grain in the husband’s store and any income generated from it because of their high labor contribution in producing the grain. The “milk bottle” technique revealed that wives begin indicating to the husband that their stores are empty when the stores still contained about 36% of their harvest. This contrasted with men who considered a store “empty” when only 17% of the grain in store is left. Because the wives get grain allocations from the husband’s store when they run out of grain, this may suggest that wives seek to access the grain as early in the season as possible after indicating that their own stocks had been exhausted. Perhaps this is in order to have better control over the uses of the grain because once it is in their store, the husband has little control. It might also suggest that women are more concerned about food security (i.e., ensuring food availability) than men so they are more comfortable giving an early warning on grain depletion. Early access to the grain may also enable women to continue to pursue their own interests since if they can have access to both the grain from the husband’s store and their own, there is an added element of food security and flexibility. The polygamous husband reported that he generally does not begin to allocate his grain before September after harvesting in March/April. However, further probing revealed that this was not a strict rule and the husband can usually be persuaded to share the grain much earlier, showing that the women have some bargaining power. The women also reported that they could withhold their contribution of cooked food from the husband to demonstrate that their stores are depleted and they thus needed access to grain in the husband’s store. The extent to which this type of bargaining is done is dependent on the co-operation between wives. However, it should be noted that accessing the husband’s store too early may have a negative effect on general household food security and this alone may affect women’s decisions regarding the use of this bargaining tool.

Store ownership has an effect on the management strategies employed. Individual store owners manage their stores as they wish and only have joint interests pertaining to household food security. The need for bargaining for preferred use of grain is greater when there is one common store compared to individually owned stores.

While bargaining between and within gender remains shrouded in subtleness, our interpretation is that individuals in a household consciously use their skills to manipulate the situation to their best advantage. This was particularly evident in all three households, i.e., the households with two wives, mother and daughter-in-law, and the two sisters-in-law. Thus the simple monogamous household was the sole exception.

What bargaining goes on between men and women in store management and grain sales?

Bargaining and negotiating focuses around issues such as income generation and preferred use of the grain. Uses of grain differ between men and women. The case studies show that women are more concerned with issues of household food security than men and that women will use their bargaining power to ensure that they and the children are food secure. Preferred use of grain also differs between women within households. For example in the polygamous household, the senior wife was concerned with grain for helping the extended family and neighbors while the junior wife was concerned with grain for paying casual labor on her field. This may be because she has fewer children to help her to produce grain on her field. Wives in this same household were able to use the fact that manual sorghum processing has a high labor demand as a way of ensuring that maize was used as the primary grain for consumption while sorghum was used by the wives for beer brewing and paying casual labor. Women are likely to bargain for more stored grain which they may be able to exert more control over, especially if they have little control over the income generated from bulk grain sales. In Case study 3, the wife was able to suggest to the husband that he sell one of his goats rather than use money generated from mid-season sales which she has more control over. It can be argued that women are concerned with uses of grain or income from grain sales, which translate into improved conditions (an easier life) for themselves.

For the polygamous household, the methods of bargaining over issues can be varied because wives can work together using the comparative advantages of their positions to optimize their overall conditions. For example when working together, the senior wife may send the junior wife to do the bargaining in cases where her position as the young and favored wife may be an advantage. It can be argued that if the wives team up against the husband on an issue, they have a comparatively stronger bargaining tool than as individuals. The polygamous household also offers wives the opportunity to use disagreements between themselves as a tool to bargain since the husband may be interested in re-establishing peace within the household. The degree to which these tools are used depend on the circumstances in which wives may find themselves. However, falling completely out of favor with the husband may result in a new wife being brought in by the husband, a change which may be far from desirable for the concerned wife or wives. Bargaining issues were also detected in the area of management of finances obtained from bulk sales. Men participated more than women in price bargaining with potential grain buyers because the men regarded themselves as more “educated” or “enlightened” than the women. Even in terms of the management of the income generated from bulk sales, men felt that they were better able to decide on major household items or agricultural inputs because they were relatively more “exposed” than their female counterparts. This portrays a typical superiority attitude by men towards women.

Conclusions and implications of the study

Based on the household profile data and analysis of context-specific questions, we obtained a good understanding of the underlying processes of bargaining and strategizing and the circumstances in which they occur. Generally, the gender roles in store management and grain marketing within all case study households adhere to the normative roles. However, the normative gender roles can be changed to suit the different household profiles depending on the degree of co-operation between men and women and between women within households. Roles become more flexible between different groups of women as the household becomes complex because this complexity creates more room for strategies like delegation and/or sharing of roles or assuming new roles (as in the case where the wife is the de facto head of household). Women in polygamous households use multiple strategies when bargaining with the husband and have higher potential leverage, especially when they combine forces.

Household strategies for store management result from a great deal of co-operation between husbands and wives as both work towards household food security and other joint or separate livelihood goals. The strategies employed by women shift and change over time depending on whether their interests lie in promoting their security and/or their status within the household and/or their level of self-reliance. Bargaining in store management remains centered on ensuring that the distribution of income from grain jointly produced is fairly distributed between household needs as well as husbands and wives’ individual needs. Much bargaining surrounds the preferred use of grain (e.g., sales vs. consumption as well as sales vs. labor payment). Women will try to ensure that their needs are met by trading off one use for another, e.g., a woman with a high labor requirement may opt for fewer mid-season sales and use her grain to pay for casual labor. Although this means less income for her, it does ensure food security in the coming year when higher yields are obtained, which may be a more important factor to her. The study showed that although the status of women may be far from satisfactory in terms of equity and empowerment within households and society at large, there are many forces of change and types of “power-play” being employed by women in order to optimize their conditions within the confines of societal norms.

The shifts between conflict versus co-operation between and within the different genders are complex and subtle. Women in monogamous marriages are less independent in terms of their individual or separate interests; in contrast, in the polygamous household wives are more autonomous with respect to grain in their own stores since they can decide to sell stored grain or use it otherwise.

The study showed that men participate more in grain price bargaining during bulk sales after harvesting compared to women. Men largely control income from bulk sales at the beginning of the storage season whereas that from mid-season sales is the domain of women. Women’s keen interest in mid-season income lies in the fact that it contributes to their self-reliance and supplements urgent household needs. Men regard the money generated from mid-season grain sales as relatively insignificant for purchase of major items. However, women value this income and use it as a way of maintaining and supporting their individual interests both within and outside the household. Women’s interest in the finances is a strategy to prevent their husbands “misusing” the money by marrying another wife who then disadvantages the incumbent wife and “her” children. The case studies show that women are more concerned with issues of household food security than men and that women will use their bargaining power to ensure that they and the children are food secure. Women are also more likely to signal warnings of store depletion earlier than men.

Use of the Locke and Okali (1999) gender analytical framework enabled us to obtain insights into the dynamics involved in gender roles and strategies. The data generated enabled us to get an idea of the potential overall impact of crop post-harvest interventions on gender at household level. Specific areas where women could benefit directly from project activities or where women are able to use the intervention as a strategy for bargaining for other benefits within the household or society in general were identified. For example, whereas it was found that no grain protectants were being applied on store grain by all the household case studies, an intervention such as the “Inert Dusts” project, which sought to provide an alternative grain protectant with protracted efficacy and persistence against storage insect pests, may provide women with more leverage for bargaining for more stored grain. This would then allow more income generation for women through mid-season sales; and the income can be used for labor payments much later in the season. The same project does not impact on the men’s preference to sell grain soon after harvesting and so may not be considered of particular importance to the men. In the case of the “Hardwoods” project, structural modifications were made to granaries which we perceived to be of benefit to the men by reducing grain store construction and maintenance requirements. It is possible to see, given a better understanding of the underlying dynamics and incentives, that this intervention may also be of benefit to the women who can now advocate for the building of separate stores where they have more control over grain usage, under the guise that store construction and maintenance is now easier.

A better understanding of the changes in gender relations and the processes by which they occur in four case study households in Binga district may help to improve the design, implementation, and evaluation of projects in the future. The study provided insights into the factors surrounding potential technology uptake in communities, and the information generated by this research needs to be considered in developing future work. We acknowledge that conclusions from case studies are not universally applicable but it must be noted that this study provides important insights into the depth to which analysis of gender relations at household level can go.

The study is also by no means meant to provide conclusive or a generalized understanding of post-harvest gender relations in the whole of Binga district or across the country. However, the case studies are specific examples which contribute to furthering the understanding of the underlying bargaining processes between and within gender groups, and of the different gender roles in post-harvest management of grain for food security, information which was not previously well documented. The article provides a basis for broader debate in the area of gender roles and bargaining in the post-harvest sub-sector which is often shrouded in secrecy at household level in sub-Saharan Africa in general.

Notes

Project R6685: Improved design of indigenous stores—Including minimizing the use of hardwood resources. The project was conducted in Binga District, Zimbabwe, primarily to reduce store and grain damage due to termite attack by replacing the indigenous hardwood main posts supporting the store base with polyvinylchloride (PVC) pipes concrete which also denied rodents access to the store. For details see Chigariro (1998).

Project R7034: Grain storage management using inert dusts. The project was implemented in three districts of Zimbabwe including Binga to reduce storage losses as means of enhancing household food security and improve income-generating opportunities by increasing farmers’ control over both the timing and scale of their grain marketing. In line with farmers safety concerns, naturally occurring inert dusts called diatomaceous earths (DEs) were tested as alternative grain protectants to the commonly used synthetic insecticides. DEs are obtained from the fossils of phytoplankton (diatoms). Details are available in Stathers et al. (2000).

The Tonga is a matrilineal society.

References

Anonymous. 2006. Mainstreaming gender, HIV/AIDS in IWRM (integrated water resources management) planning and implementation process. Handout No. 2. Harare, Zimbabwe: Global Partnership/Waternet/Institute of Water and Sanitation Development/SAFAIDS.

Beneria, L., and S. Bisnath. 1996. Gender and poverty: Analysis for action. New York: UNDP.

Boyd, C., B.M., Mvumi, I. Chatizwa, E. Nyakudya, B. Mudamburi, I. Nzuma, and M. Galpin. 1997. A participatory rural appraisal of Ward 21, Chivi District, Masvingo Province. Harare, Zimbabwe: Crop Post-Harvest Research Programme.

Chigariro, J. 1998. Assessment of sorghum grain losses in relation to storage structure modification for the smallholder in the Zambezi Valley of Zimbabwe. MSc Thesis, Natural Resources Institute, Food Security Department, University of Greenwich, Chatham, UK.

Chinyemba, M.J., O.N. Muchena, and M.B.K. Hakutangwi. 2006. Women and agriculture. In Zimbabwe’s agricultural revolution revisited, ed. M. Rukuni, P. Tawonezvi, C. Eicher, M. Munyuki-Hungwe, and P. Matondi, 631–649. Harare, Zimbabwe: University of Zimbabwe Publications.

Cleaver, F. 2000. Analyzing gender roles in community natural resource management: Negotiation, lifecourses, and social inclusion. IDS Bulletin 31 (2): 60–67.

Commutech. 1997. Socio-economic and technical factors determining community biodiversity and management: Baseline data for Tsholostho, Chiredzi, and UMP districts. Harare, Zimbabwe: SADC/GTZ project on promotion of small-scale seed production by self-help groups.

Donaldson, T.J., T. Marange, B.M. Mvumi, E. Chivandi, I. Marunda, and M. Thomas. 1997. Participatory rural appraisal (PRA) survey of Chemuonde Village, Buhera District, Manicaland Province. Harare, Zimbabwe: Crop Post-Harvest Research Programme.

Doss, C.R. 2001. Designing agricultural technology for African women farmers: Lessons from 25 years of experience. World Development 29 (12): 2075–2092.

Douglass, M.P., B.M. Mvumi, J. Chigariro, M. Mitchell, and S. Stevens. 1997. Granary design and grain storage practices in Zimbabwe’s Zambezi Valley: A survey of Binga and Kariba Districts. Harare, Zimbabwe: Crop Post-Harvest Research Programme.

Dzingai, V., and M.F.C. Bourdillon. 1998. Religious, ritual, and environmental control in the Zambezi Valley: The case of Binga. Working Paper, Centre for Applied Social Sciences, University of Zimbabwe, Harare, Zimbabwe.

Ellis, F. 2000. Rural livelihoods and diversity in developing countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

FAO. 2005. Building on gender, agro-biodiversity, and local knowledge: A training manual. Rome: FAO.

Goebel, A. 1999. “Here it is our land, the two of us”: Women, men, and land in a Zimbabwean resettlement area. Journal of Contemporary Africa Studies 17 (1): 76–96.

Horwith, B. (ed.). 1989. Gender issues in agriculture and natural resource management. New York: Robert R. Nathan Associate Inc.

Hunter, M.L., R.K. Hitchcock, and B. Wycoff-Baird. 1990. Women and wildlife in southern Africa. Conservation Biology 4 (4): 448–451.

Lloyd-Laney, M. (ed.). 1997. Making each and every farmer count: Participation in agricultural engineering projects. Harare, Zimbabwe: FAO.

Locke, C., and C. Okali. 1999. Analysing changing gender relations: Methodological challenges for gender planning. Development in Practice 9 (3): 274–286.

Locke, C., and C. Okali. 2003. Exploring “new” ways of analysing changing gender relations. Unpublished Mimeo, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK.

Marange, T., B.M. Mvumi, P. Chinwada, P. Mushayi, L. Mautsa, and J. Mhunduru. 1997. A PRA survey of Kawere Ward in Mutoko District. Harare, Zimbabwe: Crop Post-Harvest Research Programme.

Matiza, T., L.M. Zinyama, and D.J. Campbell. 1988. Household strategies for coping with food insecurity in low-rainfall areas of Zimbabwe. In Household and national food security in southern Africa, ed. G.D. Mudimu and R.H. Bernsten, 208–221. Proceedings of the fourth annual conference on food security research in Southern Africa, 31 October–3 November 1988. University of Zimbabwe/Michigan State University Food Security Research Project. Harare, Zimbabwe: Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension, University of Zimbabwe.

Nabane, N. 1994. A gender sensitive analysis of a community based wildlife utilisation initiative in Zimbabwe’s Zambezi Valley. CASS Occasional Paper Series. Harare, Zimbabwe: University of Zimbabwe.

Nabasa, J., G. Rutwara, F. Walker, and C. Were. 1995. Participatory rural appraisal: Practical experiences. Chatham, UK: Natural Resources Institute.

Nemarundwe, N. 2003. Negotiating resource access: Institutional arrangement for woodlands and water use in southern Zimbabwe. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden.

Nemarundwe, N. 2005. Women, decision making, and resource management in Zimbabwe. In The equitable forest: Diversity, community, and resource management, ed. C.J. Pierce Colfer, 150–170. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future.

Okali, C., C. Locke, and J. Mims. 2000. Guidelines for the development of gender-sensitive interventions by agricultural researchers. Draft paper for discussion. Overseas Development Group. Norwich, UK: University of East Anglia.

Pankhurst, D. 1991. Constraints and incentives in “successful” Zimbabwean peasant agriculture: The interaction between gender and class. Journal of Southern African Studies 17 (4): 611–632.

Pazvakavambwa, S.C., and M.B.K. Hakutangwi. 2006. Agricultural extension. In Zimbabwe’s agricultural revolution revisited, ed. M. Rukuni, P. Tawonezvi, C. Eicher, M. Munyuki-Hungwe, and P. Matondi, 217–233. Harare, Zimbabwe: University of Zimbabwe Publications.

Rocheleau, D. 1995. Gender and biodiversity: A feminist political ecology perspective. IDS Bulletin 26 (1): 9–16.

Sithole, B. 2005. Becoming men in our dresses! Women’s involvement in a joint forestry management project in Zimbabwe. In The equitable forest: Diversity, community, and resource management, ed. C.J. Pierce Colfer, 171–185. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future.

Stathers, T., B. Mvumi, J. Chigariro, M. Mudiwa, and P. Golob. 2000. Grain storage and pest management using inert dusts. Crop Post-harvest Programme, Final Technical Report R7034. Chatham, UK: Natural Resources Institute.

Stathers, T.E., W. Riwa, B.M. Mvumi, and M.J. Morris. 2005. Small-scale farmers utilisation of diatomaceous earths during storage. DFID Crop Post Harvest Programme Project Final Report R8179. Chatham, UK: Natural Resources Institute.

Tobisson, E. 1997. When a good design isn’t enough: Maize cribs in Kenya. In Making each and every farmer count: Participation in agricultural engineering projects, ed. M. Lloyd-Laney, 26–32. Harare, Zimbabwe: FAO.

Williams, S., J. Seed, and A. Mwau. 1994. The Oxfam gender training manual. Oxford, UK: Oxfam.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the farmers in Binga who participated in these case studies for willingly giving their time. Useful discussions were held with Catherine Locke and Christine Okali (University of East Anglia, UK) and Jonas Chigariro (Institute of Agricultural Engineering, Ministry of Agriculture, Zimbabwe) on development of tools used in the gender analysis framework. Constructive criticism of the initial draft manuscript was received from Catherine Locke and Christine Okali. The authors also acknowledge the valuable comments received from three anonymous reviewers. We are grateful to the following people who assisted in one way or the other during the process of reviewing literature: Chipo Mubaya and Bella Nyamukure (Center for Applied Social Sciences, University of Zimbabwe); Nontokozo Nemarundwe (formerly with Center for International Forestry Research—Southern Africa Region); and Christine Okali. This publication is an output from a research project funded by the United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID) for the benefit of developing countries. The views expressed are not necessarily those of DFIDR7039, Crop Post-Harvest Programme.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Manda, J., Mvumi, B.M. Gender relations in household grain storage management and marketing: the case of Binga District, Zimbabwe. Agric Hum Values 27, 85–103 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-008-9171-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-008-9171-8