Abstract

The ability to innovate is an important requirement in many organisations. Despite this pressing need, few selection systems in healthcare focus on identifying the potential for creativity and innovation and so this area has been vastly under-researched. As a first step towards understanding how we might select for creativity and innovation, this paper explores the use of a trait-based measure of creativity and innovation potential, and evaluates its efficacy for use in selection for healthcare education. This study uses a sample of 188 postgraduate physicians applying for education and training in UK General Practice. Participants completed two questionnaires (a trait-based measure of creativity and innovation, and a measure of the Big Five personality dimensions) and were also rated by assessors on creative problem solving measured during a selection centre. In exploring the construct validity of the trait-based measure of creativity and innovation, our research clarifies the associations between personality, and creativity and innovation. In particular, our study highlights the importance of motivation in the creativity and innovation process. Results also suggest that Openness to Experience is positively related to creativity and innovation whereas some aspects of Conscientiousness are negatively associated with creativity and innovation. Results broadly support the utility of using a trait-based measure of creativity and innovation in healthcare selection processes, although practically this may be best delivered as part of an interview process, rather than as a screening tool. Findings are discussed in relation to broader implications for placing more priority on creativity and innovation as selection criteria within healthcare education and training in future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Given demographic changes internationally and the speed with which patient needs and disease patterns are changing, now more than ever the healthcare sector requires students, trainees and employees who can innovate (Page 2014). Economically, the ability to innovate is one of the few strategic ways organizations can be proactive in learning how to ‘do more with less’ (Anderson et al. 2014). Despite this pressing need, few selection systems in healthcare prioritise the potential to innovate, and one challenge is how to reliably measure individual creativity and innovation.

Outside of healthcare, innovation has generated a great deal of interest, particularly around measurement at the individual level (Potocnik et al. 2015) and to what extent we can identify creativity and innovation potential during selection. In broader selection research, Conscientiousness is shown to be the single best predictor of job performance across many occupations (e.g.Schmidt and Hunter 1998). Yet this is seemingly paradoxical because Conscientiousness has been shown to be negatively related to creativity and innovation, whilst Openness to Experience is shown to be positively related (e.g. Hammond et al. 2011). If healthcare organizations require innovation they will need to explore how to select individuals with greater potential to innovate (e.g. Potocnik et al. 2015). Recruiters are thus faced with the challenge of identifying those who will innovate and also perform competently in the role.

Surprisingly little research has explored creativity and innovation within healthcare selection specifically, despite the research that does exist showing creativity and innovation to be increasingly important in this setting (Page 2014; Patterson et al. 2015). These gaps in the literature suggest more research is warranted in relation to selecting for creativity and innovation in healthcare education. In this study, we explore the use of a trait-based measure of creativity and innovation potential and evaluate its efficacy for use in selection for healthcare education. We believe this is an important first step towards understanding how practitioners might select for creativity and innovation in healthcare in future.

Defining creativity and innovation

The concepts of creativity and innovation have been debated over the years (Anderson et al. 2014; King 1992); although it is now generally agreed that the two constructs overlap. As Anderson et al. (2014) state:

“Creativity and innovation at work are the process, outcomes, and products of attempts to develop and introduce new and improved ways of doing things. The creativity stage of this process refers to idea generation, and innovation refers to the subsequent stage of implementing ideas toward better procedures, practices, or products. Creativity and innovation can occur at the level of the individual, work team, organization, or at more than one of these levels combined but will invariably result in identifiable benefits at one or more of these levels of analysis.”

Thus, in an organizational context, creativity and innovation have an anticipated benefit to the organization and a tangible output (King 1992; Patterson 2002; West and Farr 1990).

Selecting for creativity and innovation

In healthcare there is an increasing need for individuals to generate new ideas and implement these to improve working practices due to the rapid changes taking place (Anderson et al. 2014; Potocnik et al. 2015). Over several decades, research has tended to focus on identifying a core set of personality traits associated with creativity and innovation (e.g. Hammond et al. 2011), such as flexibility and openness to abstract ideas.

Of the Big Five model of personality (Goldberg 1990; McCrae and Costa 1996) research consistently shows Openness to Experience to relate positively to creativity and innovation (McCrae 1987; Batey and Furnham 2006; Feist 1998; Hammond et al. 2011; King et al. 1996; Kwang and Rodrigues 2002). Research has also shows Extroversion (King et al. 1996; Kwang and Rodrigues 2002; Martindale and Dailey 1996) to be positively associated with creativity and innovation. Conversely, Conscientiousness and Agreeableness are negatively associated with creativity and innovation (e.g. Feist 1999; King et al. 1996; Kwang and Rodrigues 2002), and yet, both Conscientiousness and Agreeableness could be seen as especially valuable for individuals entering education, training and employment in a healthcare role. In relation to Emotional Stability, there are inconsistent research findings, with some researchers finding no relationship (Aguilar-Alonso 1996; King et al. 1996) yet others finding a negative association between Emotional Stability and creativity and innovation (Feist 1998; Götz 1979; Mohan and Tiwana 1987). Inconsistent results highlight the need to identify the extent to which these findings replicate in healthcare education, a safety critical environment which requires high standards of patient care.

Our study examines the construct validity of a trait-based measure of creativity and innovation to explore its relationship with personality within healthcare. The negative association described above between Conscientiousness and creativity and innovation raises an interesting dilemma since previous research has consistently shown a positive association between Conscientiousness and various indices of training success and job performance, across a diverse range of occupations (see Barrick et al. 2001; Barrick and Mount 1991; Schmidt et al. 2008). This finding has been replicated in healthcare education settings, where Ferguson et al. (2002)found Conscientiousness to be a key predictor of medical school success and preclinical assessments for students. McLachlan and colleagues (Kelly et al. 2012; McLachlan 2010) also find Conscientiousness to be important for medical student success. However, Ferguson et al. (2002) found Conscientiousness to be a negative predictor of subsequent performance once students entered clinical practice. Conversely, in the general selection literature, whilst Openness to Experience is positively associated with innovation (e.g. King et al. 1996) and also predicts training outcomes, it is not predictive of overall job performance in general (e.g. Barrick and Mount 1991). However, in medicine, research shows (e.g. Lievens et al. 2009) that Openness to Experience predicts students’ performance overall.

These differential findings surrounding Conscientiousness may relate to the fact it is a multi-faceted construct with a broad ‘band-width’ since it comprises facets of dutifulness/dependability and also competence/achievement striving (Costa and McCrae 1992; Moon 2001). Further, research shows achievement striving and persistence to be positively related to creativity and innovation (Busse and Mansfield 1984; Sternberg and Lubart 1999) whereas being systematic and dependable is negatively associated (Patterson 1999). Thus, facet level analyses could provide a clearer understanding of how Conscientiousness relates to creativity and innovation within healthcare.

In examining the utility of a trait-based measure of creativity and innovation for use in healthcare selection, we also explore predictive validity. Identifying appropriate outcome measures for predictive validity studies remains challenging, especially for creativity or innovation (Potocnik et al. 2015). Here, we use recruiter judgements of creative problem-solving behaviour in simulation tasks (used for selection purposes) as the criterion. Certainly, an outcome measure of this nature is more useful than self-report measures of creativity or innovation used in previous studies (e.g. Axtell et al. 2000).

Organisational context

Our study focuses on a sample of postgraduate trainees applying for education and training in UK General Practice (GP). We focus on applicants for GP because this role has transformed recently with policy changes aimed at modernizing medical careers (Irish and Patterson 2010), including GPs now engaging in commissioning activities (Gregory 2009) which requires creativity and innovation in how best to deploy severely constrained resources without compromising patient care. Creativity and innovation are key requirements for GPs to deliver safe and effective services, and continually improve their practices (Clark and Armit 2010).

In summary, this research poses three research questions to examine construct and predictive validity of a trait-based measure of creativity and innovation for selection into healthcare education. We explore construct validity by examining the association between a trait-based measure of creativity/innovation and a Big Five measure of personality; and we evaluate predictive validity by exploring the extent to which these measures predict subsequent creative problem-solving behaviour in a selection centre. Our research questions are as follows:

-

1.

Construct validity: To what extent are creativity and innovation related to Big Five Factors of personality?

-

2.

Construct validity: What is the relationship between creativity and innovation and the facets of Conscientiousness?

-

3.

Predictive validity: Does a trait-based measure of creativity and innovation offer any advantage over the Big Five dimensions of personality in predicting creative problem-solving behaviour assessed during selection?

Method

Participants and procedure

Participants were UK postgraduate medical students in the Sheffield region and were in their second year of UK Foundation training, applying for training in GP. All participants completed the questionnaires (100% response rate). Participants were attending a selection centre which targeted five performance dimensions including; Empathy, Creative Problem-Solving Behaviour; Professional Integrity; Coping with Pressure and Clinical Expertise. Of these, Creative Problem-Solving Behaviour was judged to be most closely related to creativity and innovation because it measured indicators such as thinks conceptually; uses critical analysis to think around issues and formulate solutions; open to ideas and suggestions from others.

In the selection centre, three simulation exercises (each lasting 20–40 min) measured Creative Problem-Solving Behaviour, and content was devised based on multi-method job analysis study (Patterson et al. 2013). The first exercise was a simulated consultation, where the candidate took the role of a GP physician and a trained role actor simulated a patient in a given scenario. The second exercise was a group discussion exercise, where four candidates were asked to discuss and resolve a work-related issue. The third exercise was a written planning exercise, in which candidates were asked to prioritize a set of impending work-related issues, justifying the order chosen. In the simulations, candidates were scored by trained assessors on each dimension using a 4-point rating scale (1 = poor; 4 = excellent) with behavioural anchors. As only one assessor was scoring candidates’ behaviour at any given time, it was not possible to compute inter-rater reliability; however, the validity of this selection centre has been demonstrated in numerous studies (Gale et al. 2010; Lievens and Patterson 2011; Patterson et al. 2013). The outcome measure was taken as the mean rating for Creative Problem-Solving Behaviour across the three different simulations. All participants were consented and voluntarily participated in this research.

Measures

Innovation potential indicator (IPI)

The IPI is an established 30-item trait-based measure of an individual’s creative and innovative behaviour comprising four dimensions (Motivation to Change, Challenging Behaviour, Consistency of Work Style and Adaptation). It has been used in organisations for selection and development (Patterson 1999; Burch et al. 2008) and its utility has been established in sectors other than healthcare (Zibarras et al. 2008; Burch et al. 2008). The items are a set of behavioural statements asking about preferred style of working. Respondents indicate the extent to which they agree with items along a five-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The IPI dimensions and example items are outlined in Table 1 (see Zibarras et al. 2008; Burch et al. 2008).

NEO PI-R

The NEO PI-R (Costa and McCrae 1992) is a well-established, widely-used measure of personality covering five major domains of personality. Within each domain there are six facets; thus there are 30 scales with an average of eight items per scale. Respondents are required to indicate the extent to which they agree with items along a five-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). See Table 1 for more information about the measure.

Results

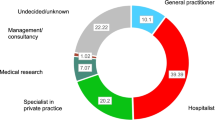

The final sample included 188 participants, 49% of whom were male and 51% were female. The mean age was 30.2 years (SD = 7 years) and the mean time since qualification as a doctor was 5.7 years (SD = 6.7 years). The participants reported their ethnic origin as follows: White 56.4%; Black-African 6.4%; Indian 19.7%; Pakistan 8%; Bangladeshi 0.5%; Chinese 1.1% and Other Ethnic Group 8.0%.

The descriptives and correlations between the IPI scales with the Big Five dimensions are presented in Table 2.

-

1.

To what extent are the creativity/innovation traits related to Big Five Factors of personality?

Findings showed that Openness to Experience was positively related to Motivation to Change (r = .39, p < .001) and negatively related to Adaptation (r = −25, p = .003). Conscientiousness was positively related to Motivation to Change (r = .17, p = .04) and Consistency of Work Styles (r = .41, p < .001); and negatively related to Challenging Behaviour (r = −21, p = .02). Neuroticism was negatively related to Motivation to Change (r = −28, p = .001) and Extraversion was positively related to Motivation to Change (r = .22, p = .01).

-

2.

What is the relationship between creativity and innovation and the facets of Conscientiousness?

Results in Table 2 show that Motivation to Change is positively related to Competence (r = .22, p = .009), Achievement Striving (r = .25, p = .003), and Self-Discipline (r = .30, p < .001). Consistency of Work Styles is positively correlated with all the facets of Conscientiousness, although notably the three highest correlations are Dutifulness (r = .32, p < .001), Order (r = .40, p < .001), and Deliberation (r = .29, p < .001). Challenging Behaviour was negatively related to Competence (r = −20, p = .02), Dutifulness (r = −27, p = .001) and Self-Discipline (r = −20, p = .02).

-

3.

Does a trait-based measure of creativity and innovation offer any advantage over the Big Five dimensions of personality in predicting creative problem-solving behaviour assessed during selection?

In order to examine the third research question, we conducted a hierarchical regression analysis. Following pre-analysis checks (e.g. Field 2005; Miles and Shevlin 2001), a hierarchical regression equation was calculated with CPS as the dependent variable. The Big Five Factors were entered in Step 1, and the IPI scales were entered in Step 2.

Table 3 shows that the addition of the Big Five domains in Step 1 predicted Creative Problem-Solving Behaviour; R2 = .13, F(5129) = 3.87, p = .003; the beta-weight for Extraversion (β = .24, p = .01) was significant. The addition of the IPI scales in step 2, significantly added to the prediction of Creative Problem-Solving Behaviour, ∆R2 = .07, F(4125) = 2.68, p = .03; with a significant beta-weight for Motivation To Change (β = .26, p = .006).

Discussion

Creativity and innovation have not previously been examined for use as selection criteria in healthcare education and training. This study offers a preliminary evaluation of a trait-based measure of creativity and innovation as a possible selection tool in this context. Our findings highlight three key contributions to the research literature. First, our study was based in a healthcare context, using a sample of postgraduate applicants for GP training. With the shift in GP’s working practices to become more innovative, selection may be more directed towards employees who actively engage in change, and individuals who are motivated to achieve despite the ambiguity inherent in the role. Our findings might question the approach adopted by traditional selection processes that are aimed at fitting the person’s current skill set to the role (Koczwara and Ashworth 2013). Given the pace of change and shift in career patterns, perhaps it would be wise to re-visit this approach and move towards techniques that assess learning potential, for example. By implication this may increase the potential for innovation to occur.

Secondly, in exploring the construct validity of the trait-based measure of creativity and innovation, our research clarifies the associations between personality, and creativity and innovation. In line with earlier research (Batey and Furnham 2006; Feist 1999; King et al. 1996; McCrae and Costa 1996), results show Openness to Experience to be positively correlated with creativity and innovation outcomes. Associations were found between Motivation to Change and both Extraversion (positive relationship) and Neuroticism (negative relationship), replicating similar findings elsewhere in the literature (e.g. King et al. 1996; McCrae and Costa 1996; Marcati et al. 2008); indeed, given that Emotional Stability (that is, low Neuroticism) predicts work performance across occupations (e.g. Barrick et al. 2001), our findings may also reflect the need for Emotional Stability to innovate. No relationship was found between Agreeableness and the creativity and innovation traits.

Conscientiousness was positively correlated with two of the IPI scales (Motivation to Change and Consistency of Work Styles), but negatively related to Challenging Behaviour. Previous research has reported a negative relationship between innovation and Conscientiousness (e.g. King et al. 1996), and indeed many practitioners assume that low Conscientiousness is important for innovators (perhaps because low Conscientiousness is associated with flexibility). However, the Big Five personality framework may be too broad to predict criteria such as creativity and innovation behaviour (Hough 1992); thus our examination of Conscientiousness at the facet level is revealing. Findings showed that Achievement Striving, Competence and Self-Discipline are positively related to innovative traits, whilst Deliberation, Order and Dutifulness facets are not. Interestingly, Motivation to Change correlates with only three facets of Conscientiousness, notably Achievement Striving, Competence and Self-Discipline which fits with other evidence suggesting that aspects of Conscientiousness relate to motivational factors (see Barrick et al. 2002). Such factors include goal setting and goal commitment, which may in turn mediate the effects of conscientiousness in predicting both training and job performance (Klein and Lee 2006).

Thirdly, our results confirm the important role of motivation in creativity and innovation. Indeed, when exploring the predictive validity of the IPI, Motivation to Change is the only significant predictor of creative problem solving, over and above personality traits. Amabile and colleagues (e.g. Amabile et al. 1996; Amabile and Gryskiewicz 1989; Amabile 1996) have been influential in this area, proposing the role of motivation in the creativity and innovation process. Amabile’s work implies that intrinsic and extrinsic motivation play different parts, whereby intrinsic motivation is important in tasks that require novelty, but extrinsic motivators may be a distraction during the creativity stages of the innovation process. However, later on, where evaluation of ideas and persistence are required, extrinsic motivators may help individuals to persist in solving a problem within a given domain. In examining the importance of motivation in the creativity and innovation process, it is also possible to see how supervisors can impact this process as well. Evidence suggests that supervisors may influence (either positively or negatively) an individual’s motivation towards creativity/innovation (Patterson et al. 2012) and thus the individual-supervisor relationship can either facilitate or inhibit creativity and innovation. This is why supervisors have been described as important “gatekeepers” for innovation and creativity (Patterson et al. 2012).

Practical implications

We highlight two important practical implications that can be drawn from this research. First, our research is a first step towards confirming the potential utility of the trait-based measure of creativity/innovation for use in selection for healthcare education. For example, it could be used to guide questioning in a multiple mini-interview station focusing on creativity and innovation. Other selection methods might also be used to identify innovative individuals, for example Anderson et al. (2014) consider various selection methods, including situational judgement tests, and work samples focused on creativity and innovative behaviour. It must be noted that whilst certain selection methods may offer benefits to the selection process in identifying candidates who are more likely to innovate, such methods should not replace the need for methods that focus on the clinical competence required for the role. Indeed, this research highlights a key challenge for selection given that Conscientiousness may need to be differentially treated in a selection process depending on whether creativity and innovation are key requirements. Furthermore, even if you select people who have the propensity to innovate, this potential might not be realized when they enter clinical practice. This is because an individual’s efforts to implement innovations in their clinical practice is contingent on organizational and team culture, and the support they receive for innovating (Anderson et al. 2014; Hammond et al. 2011).

Second, when implementing selection methods, these will require validation studies to assess the extent to which people actually engage in creative and innovative behaviours in the workplace. However, this raises the question: what is creative/innovative behaviour in healthcare? Potocnik and colleagues (2015) point out that whilst overall performance includes fulfilment of assigned duties and tasks, innovative behaviour, by definition, implies something new or previously unknown which is difficult to predict. Thus further research is required to explore the most appropriate criterion measures for validating any selection measure focusing on creativity and innovation. Here, we measured creative problem solving behaviour (judged by assessors in simulations in a selection centre), which was a proxy measure of creative/innovative performance. Nevertheless, future research could usefully needs explore other outcome measures (e.g. in- training supervisor ratings) ideally including objective criteria (e.g. new service developments), Potocnik et al. 2015).

Limitations

There are a number of limitations of this research that should be noted. First, we acknowledge that our criterion measure is only one indicator and more objective measures (over a longer period of time) would strengthen the findings. Second, it must be noted that we only explored creativity and innovation at the individual level of analysis, focusing predominantly on a trait-based approach. A multi-level analysis is needed to fully understand the important variables in creativity/innovation as the role of workgroups, teams, managers and organizational culture will influence the outcomes. Third, our sample used was a specific, homogeneous group, and relatively small. Therefore future research is needed to explore the extent to which our findings are generalizable across wider and more diverse contexts. Finally, we acknowledge that trait-based measures in selection assumes that traits are stable over time, however recent literature (see for example Ferguson & Lievens in this volume) highlight that traits are dynamically linked to the context so that traits may change and influence how a behaviour is expressed across contexts (otherwise known as trait expressions). Therefore, we propose any trait-based measure in selection is best used alongside an interview, where different contexts can be explored with the applicant. Measurement of creativity and innovation potential continues to be challenging but we argue this is a worthy area for pursuit since compared to other professions, it has been vastly under-researched within in healthcare.

References

Aguilar-Alonso, A. (1996). Personality and creativity. Personality and Individual Differences, 21(6), 959–969.

Amabile, T. (1996). Creativity in context: Update to the Social Psychology of Creativity. New York: Westview Press.

Amabile, T. M., Conti, R., Coon, H., Lazenby, J., & Herron, M. (1996). Assessing the work environment for creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 1154–1184.

Amabile, T. M., & Gryskiewicz, N. D. (1989). The creative environment scales: Work environment inventory. Creativity Research Journal, 2(4), 231–253.

Anderson, N., Potocnik, K., & Zhou, J. (2014). Innovation and creativity in organizations: a state-of-the-science review, prospective commentary, and guiding framework. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1297–1333. doi:10.1177/0149206314527128.

Axtell, C. M., Holman, D. J., Unsworth, K. L., Wall, T. D., Waterson, P. E., & Harrington, E. (2000). Shopfloor innovation: Facilitating the suggestion and implementation of ideas. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 73(3), 265–285.

Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1991). The Big Five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44(1), 1–26.

Barrick, M. R., Mount, M. K., & Judge, T. A. (2001). Personality and performance at the beginning of the new millennium: What do we know and where do we go next? International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 9(1&2), 9–30.

Barrick, M. R., Stewart, G. L., & Piotrowski, M. (2002). Personality and job performance: Test of the mediating effects of motivation among sales representatives. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(1), 43.

Batey, M., & Furnham, A. (2006). Creativity, intelligence, and personality: A critical review of the scattered literature. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 132(4), 355–429.

Burch, G. S. J., Pavelis, C., & Port, R. L. (2008). Selecting for creativity and innovation: The relationship between the innovation potential indicator and the team selection inventory. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 16(2), 177–181.

Busse, T. V., & Mansfield, R. S. (1984). Selected personality traits and achievement in male scientists. Journal of Psychology, 116, 117–131.

Clark, J., & Armit, K. (2010). Leadership competency for doctors: a framework. Leadership in Health Services. Retrieved from http://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/pdf/10.1108/17511871011040706

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Neo PI-R Professional Manual. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Feist, G. J. (1998). A meta-analysis of personality in scientific and artistic creativity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 2(4), 290–309.

Feist, G. J. (1999). The influence of personality on artistic and scientific creativity. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 273–296). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ferguson, E., James, D., & Madeley, L. (2002). Factors associated with success in medical school: systematic review of the literature. British Medical Journal, 324(7343), 952–957.

Field, A. (2005). Discovering statistics using SPSS. Sage publications.

Gale, T. C. E., Roberts, M. J., Sice, P. J., Langton, J. A., Patterson, F. C., Carr, A. S., et al. (2010). Predictive validity of a selection centre testing non-technical skills for recruitment to training in anaesthesia. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 105(5), 603–609. doi:10.1093/bja/aeq228.

Goldberg, L. R. (1990). An alternative“description of personality”: the Big-Five factor structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(6), 1216–1229.

Götz, K. O. (1979). Personality characteristics of professional artists. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 49(1), 327–334.

Gregory, S. (2009). General practice in England: An overview. Retrieved from http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/general-practice-in-england-overview-sarah-gregory-kings-fund-september-2009.pdf

Hammond, M. M., Neff, N. L., Farr, J. L., Schwall, A. R., & Zhao, X. (2011). Predictors of individual-level innovation at work: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts2, 5(1), 90–105.

Hough, L. M. (1992). The ‘Big Five’ personality variables–construct confusion: Description versus prediction. Human performance, 5(12), 139–155.

Irish, B., & Patterson, F. (2010). Selecting general practice specialty trainees: where next? British Journal of General Practice, 60(580), 849–852. Retrieved from http://bjgp.org/content/60/580/849.short

Kelly, M., O’Flynn, S., McLachlan, J., & Sawdon, M. A. (2012). The clinical conscientiousness index: A valid tool for exploring professionalism in the clinical undergraduate setting. Academic Medicine, 97(9), 1218–1224. Retrieved from http://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine/Abstract/2012/09000/The_Clinical_Conscientiousness_Index___A_Valid.21.aspx

King, N. (1992). Modelling the innovation process: An empirical comparison of approaches. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 65(2), 89–100.

King, L. A., Walker, L. M. K., & Broyles, S. J. (1996). Creativity and the Five-Factor Model. Journal of Research in Personality, 30(2), 189–203.

Klein, H. J., & Lee, S. (2006). The effects of personality on learning: The mediating role of goal setting. Human Performance, 19(1), 43–66.

Koczwara, A., & Ashworth, V. (2013). Selection and Assessment. In R. Lewis & L. Zibarras (Eds.), Work and Occupational Psychology: Integrating Theory and Practice (pp. 295–342). London: SAGE.

Kwang, N. A., & Rodrigues, D. (2002). A big-five personality profile of the adaptor and innovator. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 36(4), 254–268.

Lievens, F., Ones, D., & Dilchert, S. (2009). Personality scale validities increase throughout medical school. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(6), 1514–1535. Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/journals/apl/94/6/1514/

Lievens, F., & Patterson, F. (2011). The validity and incremental validity of knowledge tests, low-fidelity simulations, and high-fidelity simulations for predicting job performance in advanced-level high-stakes selection. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(5), 927–940.

Marcati, A., Guido, G., & Peluso, A. M. (2008). The role of SME entrepreneurs’ innovativeness and personality in the adoption of innovations. Research Policy, 37(9), 1579–1590.

Martindale, C., & Dailey, A. (1996). Creativity, primary process cognition and personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 20(4), 409–414.

McCrae, R. R. (1987). Creativity, divergent thinking, and openness to experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(6), 1258–1265.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1996). Toward a new generation of personality theories: Theoretical contexts for the five-factor model. In J. S. Wiggins (Ed.), The Five Factor Model of Personality. London: The Guilford Press.

McLachlan, J. (2010). Measuring conscientiousness and professionalism in undergraduate medical students. The Clinical Teacher, 7(1), 37–40. doi:10.1111/j.1743-498X.2009.00338.x.

Miles, J., & Shevlin, M. (2001). Applying regression & correlation: A guide for students and researchers. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Mohan, J., & Tiwana, M. (1987). Personality and alienation of creative writers: A brief report. Personality and Individual Differences, 8(3), 449.

Moon, H. (2001). The two faces of conscientiousness: Duty and achievement striving in escalation of commitment dilemmas. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 533–540.

Page, T. (2014). Notions of innovation in healthcare services and products. International Journal of Innovation and Sustainable Development. Retrieved from http://www.inderscienceonline.com/doi/abs/10.1504/IJISD.2014.066609

Patterson, F. (1999). The innovation potential indicator. Manual and User’s guide. Oxford: OPP Ltd.

Patterson, F. (2002). Great minds don’t think alike? Person-level predictors of innovation at work. International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 17, 115–144.

Patterson, F., Kerrin, M., & Zibarras, L. (2012). Employee Innovation. In T. S. Pitsis, A. Simpson, & E. Dehlin (Eds.), The Handbook of Organizational and Managerial Innovation (pp. 163–188). London: Edward-Elgar Press.

Patterson, F., Knight, A., Dowell, J., Nicholson, S., Cousans, F., & Cleleand, J. (2015). How effective are selection methods in medical eduction and training? Evidence from a systematic review. Medical Education

Patterson, F., Lievens, F., Kerrin, M., Munro, N., & Irish, B. (2013). The predictive validity of selection for entry into postgraduate training in general practice: Evidence from three longitudinal studies. The British Journal of General Practice: The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 63(616), e734–e741. doi:10.3399/bjgp13X674413.

Potocnik, K., Anderson, N., & Latorre, F. (2015). Selecting for Innovation. In I. Nikolaou & J. K. Oostrom (Eds.), Employee recruitment, selection and assessment: Contemporary issues for theory and practice. London: Psychology Press.

Schmidt, F., & Hunter, J. E. (1998). The validity and utility of selection methods in personnel psychology: Practical and theoretical implications of 85 years of research findings. Psychological Bulletin, 124(2), 262–274.

Schmidt, F. L., Shaffer, J. A., & Oh, I. S. (2008). Increased accuracy for range restriction corrections: Implications for the role of personality and general mental ability in job and training performance. Personnel Psychology, 61(4), 827–868. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2008.00132.x.

Sternberg, R. J., & Lubart, T. I. (1999). The concept of creativity: Prospects and paradigms. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of Creativity (pp. 3–15). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

West, M. A., & Farr, J. L. (1990). Innovation and creativity at work: Psychological and organizational strategies. John Wiley & Sons Inc

Zibarras, L. D., Port, R. L., & Woods, S. A. (2008). Innovation and the ‘Dark Side’ of personality: dysfunctional traits and their relation to innovation potential. Journal of Creative Behavior, 42, 201–215.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Patterson, F., Zibarras, L.D. Selecting for creativity and innovation potential: implications for practice in healthcare education. Adv in Health Sci Educ 22, 417–428 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-016-9731-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-016-9731-4