Abstract

Hypotension is a frequent complication of spinal anaesthesia for caesarean section and can threaten the well-being of the unborn child. Numerous randomised controlled trials (RCTs) dealt with measures to prevent hypotension. The aim of this study was to determine the reporting quality of RCTs using the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement since low quality can lend false credibility to a study and overestimate the effect of an intervention. We performed a systematic literature search in PubMed to identify relevant RCTs in a pre-CONSORT period (1990–1994) and a post-CONSORT period (2004–2008). A comparative evaluation was done between the two periods, and the trials were assessed for compliance with each of the 22 CONSORT items. A total of 37 RCTs was identified. The CONSORT score increased significantly (p < 0.05) from 66.7% (±12.5%) in the pre-CONSORT period to 87.4% (±6.9%) in the post-CONSORT period. A statistically significant improvement was found for eight items, including randomization, blinding and intention-to-treat analysis. The CONSORT score in the post-CONSORT era was fairly good, also in comparison to other medical fields. In the post-CONSORT era, reporting of important items improved, in particular in the domains that are crucial to avoid bias and to improve internal validity. Use of CONSORT should be encouraged in order to keep or even improve the reporting quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hypotension is considered a major side effect of spinal anaesthesia for caesarean section that can compromise foetal circulation, causing hypoxia and foetal acidosis in the unborn baby [1]. Many randomised controlled trials (RCTs), the gold standard of clinical research, were undertaken to study measures aiming to prevent hypotension. In a previous report, we demonstrated that research in this field is limited by a wide variety of definitions of hypotension making it difficult if not impossible to compare the results of the RCTs [2].

The present study sought to evaluate the quality of RCTs in this field. Incomplete data reporting and methodological flaws can limit the value of a RCT. In order to avoid that poor studies receive false credibility, readers need to evaluate the quality of the methods. In response to growing concerns about the quality of clinical trials, a group of 30 experts including medical journal editors, clinical trialists, epidemiologists and methodologists identified 22 items for which there was evidence that inadequate reporting can introduce bias. A checklist containing all 22 items and a flow diagram were designed, both instruments examining transparent reporting of chronological enrolment, intervention allocation, follow-up and data analysis. So the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement was developed and first published in 1996; a revised version was issued in 2001 [3].

There is evidence that studies with a low-quality reporting tend to overestimate the effect of the evaluated intervention by 30–50% [4]. For the assessment of quality of reporting of clinical studies, the CONSORT tool offers some advantages. Proper performance of randomisation, blinding of randomisation and blinding of the subjects and investigators to study interventions will help to reduce bias in clinical studies [5]. Eligibility criteria relate to the external validity of the study, assisting the clinician to decide whether the results of the trial can be applied to his own patients. Scientific validity is reflected by aspects involving statistical analysis. In addition, standards for abstract and title facilitate the process of finding relevant articles.

Since quality of reporting RCTs of interventions to prevent hypotension due to spinal anaesthesia in parturients undergoing caesarean section has not been systematically assessed the present study applied the CONSORT checklist to RCTs. We compared a period before CONSORT (1990–1994) with a post-CONSORT period (2004–2008).

Methods

To identify relevant literature, we performed a PubMed with the search terms “caesarean section” and “hypotension” and “randomised controlled trial” as well as a hand-search of anaesthesiologic journals, the journals Obstetrics and Gynecology as well as the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. The search was restricted to articles in English language. Two periods were searched: A first period comprised the time from January 1, 1990 until December 31, 1994. The second period ranged from January 1, 2004 until December 31, 2008.

The retrieved articles were then independently screened for eligibility by two authors. Studies were included into this review when healthy parturients scheduled for caesarean section under spinal anaesthesia were randomly assigned to at least one intervention arm that aimed to prevent or treat anaesthesia-induced hypotension. In agreement with others [6], blinding of the graders was not performed since research on the impact of blinding on the evaluation of quality of RCTs has yielded ambiguous results [7, 8].

The CONSORT statement was used to evaluate the reporting quality of the included trials. Each of the 22 CONSORT items was graded as either “yes” or “no”. In case that blinding was not possible, a “not applicable” was also possible. The CONSORT score of each RCT was calculated by adding the correctly reported domains of the CONSORT checklist and expressed as percentage of the maximally available number (in general out of 22, out of 21 in cases that blinding was not possible). All domains had the same weight.

For the purpose of this study, the reviewers underwent systematic training. Initially, they received the German version of the “Revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomised trials: Explanation and elaboration document” which provides the meaning of each item and examples of good practise. Consecutively, they were trained by scoring two articles that were not part of this review.

All reports were independently graded by two investigators. According to our protocol, a third reviewer had to be involved if consensus was not reached between the two first investigators.

To assess chance-adjusted interrater reliability, Cohen’s kappa statistic was determined. This method involves the degree of reviewers’ agreement on whether a domain was reported or not. It was calculated for three articles that were not included into this study.

The articles were grouped by publication period (1990–1994: pre-CONSORT; 2004–2008: post-CONSORT). The pre- and post-CONSORT periods were compared by calculating the odds ratio and the 95% confidence interval for each domain. CONSORT scores are given as mean ± standard deviation. Student’s t test served for the comparison of CONSORT scores in the two periods. The level of statistical significance was set at the two-sided 0.05 value.

Findings

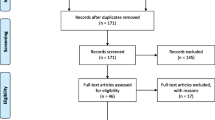

We identified 48 articles with our search strategy of which 37 [9–45] met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). All articles found by the hand-search were also retrieved by the PubMed search. Of these 37 articles, 13 were published in the pre-CONSORT period (1990–1994) and 24 in the post-CONSORT period (2004–2008). Table 1 shows the sources of the retrieved articles, 33 articles were published in anaesthesiologic journals, two in obstetric journals and two others in general medical journals.

The CONSORT scores increased from 66.7 ± 12.5% in the pre-CONSORT period to 87.4 ± 6.9% in the post-CONSORT era (p < 0.01). Agreement between the evaluators was good with a k = 0.94 (0.92–0.96).

Figure 2 portrays the percentage of correctly described CONSORT items in the pre- and post-CONSORT era. More than a third of all articles from both periods reported 90–100% correctly, and only 5% had a correct reporting of 40–50% of the CONSORT items. When comparing the two time periods, a significant improvement was observed in eight items including sample size calculation, method of randomization, implementation of randomization, blinding, statistical methods, participant flow, intention-to-treat analysis (ITT) and generalizability. A non-significant improvement was found for endpoints, allocation concealment, baseline data, outcomes and estimation of effect, ancillary analysis, interpretation of results and overall evidence (Table 2). For two items, a decrease of correctly reporting articles was found, i.e. recruitment and follow-up as well as adverse effects. In the pre-CONSORT period, five domains were correctly reported in all 13 articles.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating the compliance with CONSORT of RCTs dealing with hypotension due to spinal anaesthesia for caesarean section. Our approach of studying a period before publication of CONSORT with a time period thereafter has several precedents [6, 46, 47].

As a major result, we found a significant increase in the CONSORT scores from 66.7% to 87.4%. Also, a statistically significant improvement was observed for eight items after CONSORT was published and an improvement in seven items that did not reach statistical significance. Of the total of 22 items, five items were already correctly reported in the pre-CONSORT era.

A remarkable improvement in the items relating to randomization was found. This is critical for the detection of selection bias, and deficiencies were associated with an exaggeration of the treatment effect [4, 48]. Another area of improvement was the participant flow diagram which is intended to explicitly report the number of subjects undergoing randomization, receiving treatment, the number of dropouts and the number finally being analysed [49].

ITT was used by all reports of the post-CONSORT era versus ten out of 13 pre-CONSORT articles. ITT is strongly recommended since it preserves the randomization process and allows for non-compliance and deviations from policy [50]. ITT together with methods of randomization and blinding is crucial for internal validity and helps to avoid selection, performance, detection and attrition bias [5].

Sample size calculation was an item that showed the sharpest increase over time, i.e. the percentage of trails correctly reporting on this item increased from 23% (three of 13 reports) to 71% (17 of 24 reports) in the post-CONSORT period. Sample size calculation is required to quantitatively estimate the power of a trial to answer the studied question [46]. Underpowered trials are prone to bias and can negatively affect the quality of meta-analyses [46]. However, it has to be emphasized that this CONSORT item only evaluates whether a sample size calculation has been performed but it does not give information of whether this calculation is correct or not.

Interestingly, our analysis found a lower percentage of correct reporting for the items recruitment and follow-up as well as adverse effects in the post- versus the pre-CONSORT period, although statistically not significant. It could be speculated that the reporting of adverse effects was omitted since authors feared that the occurrence of side effects and complications could question their positive results and lead to a rejection of the manuscript. The fact that inadequate reporting is found in the more recent papers could be due to the increasing competition in the academic field leading to a growing pressure to produce publications, since the number of authored papers is one of the parameters for evaluating scientific careers [51, 52]. A report that evaluated surgical papers which were published in 2005 confirmed our finding of a high rate of inadequate reporting of adverse effects [53]. Editors should probably draw the conclusion that authors have to be encouraged to report on undesired effects. Proper definition and reporting of adverse events is crucial for critical appraisal of study results and, in addition, facilitates systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Previous studies showed that acute surveillance, i.e. actively asking study subjects whether undesired events occurred by use of structured questionnaires, interviews or diagnostic tests at predefined time intervals, is more effective than passive disclosure [44, 45]. Reporting of adverse events should already be considered during study design since data on adverse events are less susceptible to bias and confounders when they are collected prospectively rather than retrospectively [54, 55]. Our finding is confirmed by a study about the reporting quality of surgical trials [53]

There are many other tools to evaluate the quality of RCTs. We chose the CONSORT checklist for several reasons. Firstly, CONSORT is officially supported by the World Association of Medical Authors and the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Secondly, several reports demonstrated that poor compliance with CONSORT criteria is associated with an exaggeration of the effect size. Moher and colleagues found that RCTs that were not double-blind overestimated the effects by 17% [4]. Inadequate or unclear allocation concealment exaggerated odds ratios by 41% and 30%, respectively. A similar finding was obtained by another group [56]. An exaggeration of the treatment effect in single RCTs by inappropriate reporting has also consequences for subsequent meta-analyses, considered to be the highest level of evidence-based medicine and often guiding our clinical practise. In their meta-analysis on anticoagulants, Lensing et al. [57] clearly favoured low molecular heparins. However, when taking quality of reporting of the underlying RCTs into consideration, superiority of low molecular weight heparin on mortality due to venous thrombosis was no longer given [4]. Exclusion of low-quality trials may thus directly impact our clinical practise.

It is probably a consequence of its widespread use that CONSORT has already been proven effective: A meta-analysis including 248 articles clearly demonstrated an improvement of the reporting of RCTs by the adoption of this tool [49]. It is noteworthy that these authors compared a time period before CONSORT publication with a period thereafter; this approach was also chosen in our report.

Thirdly, CONSORT has in the meantime been applied in many other medical specialities [53, 58]. We used the CONSORT checklist in its 2001 version. An update has been published very recently [59], after our study was completed. However, use of the 2001 version allows us to compare our results with those obtained in other medical specialities and therapeutic areas.

In only 12% of trials of analgesics given for pain relief after trauma or orthopaedic surgery sample size calculation was reported [60]. This percentage was 54% in our survey, combining the pre- and post-CONSORT period. The reason for the discrepancy could be due to the fact that the other group included trials published from 1966 on, thus covering a time period when probably little or no attention was paid to this issue, whereas our early period began much later, in 1990. In a study of nutritional support trials [58], use of blinding was found to increase significantly from 19% to 41% from a pre- (before 1996) to the post-CONSORT (after 1996) era. We observed an increase from 31% to 80%. In our study, intention-to-treat analysis was used in 76% of the pre-CONSORT and in 100% of the post-CONSORT articles, an improvement reaching statistical significance. No improvement was found for this parameter in the study by Doig and colleagues [58].

The CONSORT score of urological and non-urological surgical trials published between 2000 and 2003 was 11.1 and 11.2 (corresponding to 50.45% and 50.90%) [61], respectively, which is much lower than the CONSORT scores in either of our study periods.

Comparing our results with a study of obstetric anaesthesia trials could be of particular interest. This report by Halpern and colleagues [61] focussed on articles published from June 2000 to June 2002, providing no information on whether reporting quality might have changed over time. When comparing the reports included into this study [61], which were published between June 2000 and June 2002, with articles from our post-CONSORT era (2004–2009), we found a higher percentage of correctly reported CONSORT items in our study. More than 80% correctly reported domains were observed in 62% of our articles whereas less than 5% of the articles from the study by Halpern et al. [61] reach this value. The majority of the obstetric anaesthesia articles only ranged between 50% and 70% correctly reported items, compared to less than 5% in our sample of RCTs of interventions to prevent hypotension after spinal anaesthesia. We think it is the time difference between the two studies (2004 to 2009) in our post-CONSORT period versus June 2000 to June 2002 in the study by Halpern et al. [61] which accounts for the higher percentage of compliance with some CONSORT items in our study, since awareness of the CONSORT statement published in 1996 (respective in 2001 for the revised version) had less time to spread in the study period of Halpern et al. [61]. This notion receives further support from studies by others: Only few improvements could be observed when comparing trials from before 1996 with those appearing immediately after 1996 [60]. Moher et al. [46] also considered it a flaw of their study that their post-CONSORT period began only 12 to 18 months after publication of CONSORT. They argued that “effective dissemination is a slow process and that to estimate the true influence of CONSORT requires more time.”

It is a limitation of our study that we do not provide data on the association of quality of reporting and CONSORT adoption. We did not test for the association between the CONSORT score in adopters and non- or late adopters since every additional analysis increases the likelihood of a type I error, i.e. incorrectly inferring that there is a significant differences when there is no such difference.

In summary, the CONSORT scores increased over time from 66.7% to 87.4%, reflecting a remarkable improvement. We observed a significantly better reporting in eight of 22 items in the post-CONSORT compared to the pre-CONSORT period. However, we saw a decrease, although statistically not significant, in the reporting of adverse events which deserves further attention.

Conclusion

We conclude from our study that the reporting quality has improved significantly in the period after dissemination of the CONSORT statement. Therefore, journal editors, reviewers and authors should be encouraged to adhere to the CONSORT checklist in order to ensure high-quality trials. Consequently, clinicians can spend more time considering the findings, rather than scrutinizing quality of reporting of the trial.

References

Corke BC, Datta S, Ostheimer GW, Weiss JB, Alper MH (1982) Spinal anaesthesia for caesarean section. The influence of hypotension on neonatal outcome. Anaesthesia 37:658–662

Klöhr S, Roth R, Hofmann T, Rossaint R, Heesen M (2010) Definitions of hypotension after spinal anaesthesia for caesarean section: systematic literature search and application to parturients. Acta Anaesthiol Scand 1:1–13

Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG (2001) The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. Lancet 357:1191–1194

Moher D, Pham B, Jones A, Cook DJ, Jadad AR, Moher M, Tugwell P, Klassen TP (1998) Does quality of reports of randomised trials affect estimates of intervention efficacy reported in meta-analyses? Lancet 352:609–613

Jüni P, Altman DG, Egger M (2001) Systematic reviews in health care: assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials. BMJ 323:42–46

Moher D, Jones A, Lepage L, CONSORT group (2001) Use of the CONSORT statement and quality of reports of randomized trials: a comparative before- and after-evaluation. JAMA 285:1992–1995

Berlin JA (1997) Does blinding of readers affect the results of meta-analysis? University of Pennsylvania Meta-Analysis Blinding Study Group. Lancet 350:185–186

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynold DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ (1996) Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 17:1–12

Bhagwanjee S, Rocke DA, Rout CC, Koovarjee RV, Brijball R (1990) Prevention of hypotension following spinal anaesthesia for elective caesarean section by wrapping of the legs. Br J Anaesth 70:819–822

Moran DH, Perillo M, La Porta RF, Bader AM, Datta S (1991) Phenylephrine in the prevention of hypotension following spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery. J Cin Anesth 3:301–305

Wright PMC, Iftikhar M, Fitzpatrick KT, Moore J, Thompson W (1992) Vasopressor therapy for hypotension during epidural anesthesia for cesarean section: effects on maternal and fetal flow velocity ratios. Anesth Analg 75:56–63

Rout CC, Rocke DA, Brijball R, Koovarjee RV (1992) Prophylactic intramuscular ephedrine prior to caesarean section. Anaesth Intensive Care 20:448–452

Rout CC, Akoojee SS, Rocke DA, Gouws E (1992) Rapid administration of crystalloid preload does not decrease the incidence of hypotension after spinal anaesthesia for elective caesarean section. Br J Anaesth 68:394–397

Rout CC, Rocke DA, Levin J, Gouws E, Reddy D (1993) A reevaluation of the role of crystalloid preload in the prevention of hypotension associated with spinal anaesthesia for elective caesarean section. Anesthesiology 79:262–269

Rout CC, Rocke DA, Gouws E (1993) Leg elevation and wrapping in the prevention of hypotension following spinal anaesthesia for elective caesarean section. Anaesthesia 48:304–308

Kafle SK (1993) Intrathecal meperidine for elective caesarean section: a comparison with lidocaine. Can J Anaesth 40:718–721

Campbell DC, Douglas MJ, Pavy TJG, Merrick P, Flanagan ML, McMorland GH (1993) Comparison of the 25-gauge Whitacre with the 24-gauge Sprotte spinal needle for elective caesarean section: cost implications. Can J Anaesth 40:1131–1135

Thoren T, Holmström B, Rawal N, Schollin J, Lindeberg S, Skeppner G (1994) Sequential combined spinal epidural block versus spinal block for caesarean section: effects on maternal hypotension and neurobehavioral function of the newborn. Anesth Analg 78:1087–1092

Ramin SM, Ramin KD, Cox K, Magness RR, Shearer VE, Gant NF (1994) Comparison of prophylactic angiotensin II versus ephedrine infusion for prevention of maternal hypotension during spinal anesthesia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 171:734–739

Hall PA, Bennett A, Wilkes MP, Lewis M (1994) Spinal anaesthesia for caesarean section: comparison of infusion of phenylephrine and ephedrine. Br J Anaesth 73:471–474

Filos KS, Goudas LC, Patroni O, Polyzou V (1994) Hemodynamic and analgesic profile after intrathecal clonidine in humans. Anesthesiology 81:591–601

Loughrey JPR, Yao S, Datta S, Segal S, Pian-Smith M, Tsen LC (2005) Hemodynamic effects of spinal anesthesia and simultaneous intravenous bolus of combined phenylephrine and ephedrine versus ephedrine for cesarean delivery. Int J Obstet Anesth 14:43–47

Harten JM, Boyne I, Hannah P, Varveris D, Brown A (2005) Effects of a height and weight adjusted dose of local anesthetic for spinal anesthesia for elective caesarean section. Anaesthesia 60:348–352

Hallworth SP, Fernando R, Columb MO, Stocks GM (2005) The effect of posture and baricity on the spread of intrathecal bupivacaine for elective cesarean delivery. Anesth Analg 100:1159–1165

Kee WDN, Khaw KS, Ng FF (2005) Prevention of hypotension during spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery. Anesthesiology 103:744–750

Dahlgren G, Granath F, Pregner K, Rösblad PG, Wessel H, Irested L (2005) Colloid vs. crystalloid preloading to prevent maternal hypotension during spinal anesthesia for elective cesarean section. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 49:1200–1206

Desalu I, Kushimo OT (2005) Is ephedrine infusion more effective at preventing hypotension than traditional prehydration during spinal anaesthesia for caesarean section in African parturients? Int J Obstet Anesth 14:294–299

Davies P, French GWG (2006) A randomized trial comparing 5 ml/kg and 10 ml/kg of pentastarch as a volume preload before spinal anaesthesia for elective caesarean section. Int J Obstet Anesth 15:279–283

Hanss R, Bein B, Francksen H, Scherkl W, Bauer M, Doerges V, Steinfath M, Scholz J, Tonner PH (2006) Heart rate variability-guided prophylactic treatment of severe hypotension after subarachnoid block for elective caesarean delivery. Anesthesiology 104:635–643

Van de Velde M, Van Schoubroeck D, Jani J, Teunkens A, Missant C, Deprest J (2006) Combined spinal–epidural anesthesia for cesarean delivery: dose dependent effects of hyperbaric bupivacaine on maternal hemodynamics. Anesth Analg 103:187–190

Parpaglioni R, Frigo MG, Lemma A, Sebastiani M, Barbati G, Celleno D (2006) Minimum local anaesthetic dose (MLAD) of intrathecal levobupivacaine and ropivacaine for caesarean section. Anaesthesia 61:110–115

Coppejans HC, Hendrickx E, Goossens J, Vercauteren MP (2006) The sitting versus right lateral position during combined spinal–epidural anesthesia for cesarean delivery: block characteristics and severity of hypotension. Anesth Analg 102:243–247

Saravanan S, Kocarev M, Wilson RC, Watkins E, Columb MO, Lyons G (2006) Equivalent dose of ephedrine and phenylephrine in the prevention of post-spinal hypotension in caesarean section. Br J Anaesth 96:95–99

Ko JS, Kim CS, Cho HS, Choi DH (2007) A randomized trial of crystalloid versus colloid solution for prevention of hypotension during spinal or low-dose combined spinal–epidural anesthesia for elective cesarean delivery. Int J Obstet Anesth 16:8–12

Dahlgren G, Granath F, Wessel H, Irestedt L (2007) Prediction of hypotension during spinal anesthesia for caesarean section and its relation to the effect of crystalloid or colloid preload. Int J Obstet Anesth 16:128–134

Nishikawa K, Yokoyama N, Saito S, Goto F (2007) Comparison of the effects of rapid colloid loading before and after spinal anesthesia on maternal hemodynamics and neonatal outcomes in caesarean section. J Clin Monit Comput 21:125–129

Kundra P, Khanna S, Habeebullah S, Ravishankar M (2007) Manual displacement of the uterus during caesarean section. Anaesthesia 62:460–465

Bryson GL, MacNeil R, Jeyaraj LM, Rosaeg OP (2007) Small dose spinal bupivacaine for caesarean delivery does not reduce hypotension but accelerates motor recovery. Can J Anaesth 54:531–537

Siddiqui M, Goldszmidt E, Fallah S, Kingdom J, Windrim R, Carvalho JCA (2007) Complications of exteriorized compared with in situ uterine repair at cesarean delivery under spinal anesthesia. Obstet Gynecol 110:570–575

Kaya S, Karaman H, Erdogan H, Akyilmaz A, Turhanoglu S (2007) Combined use of low-dose bupivacaine, colloid preload and wrapping of the legs for preventing hypotension in spinal anaesthesia for Caesaren section. JIMR 35:615–625

Arai YPC, Kato N, Matsura M, Ito H, Kandatsu N, Kurokawa S, Mizutani M, Shibata Y, Komatsu T (2008) Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation at the PC-5 and PC-6 acupoints reduced the severity of hypotension after spinal anaesthesia in patients undergoing caesarean section. Br J Anaesth 100:78–81

Cesur M, Alici HA, Erdem AF, Borekci B, Silbir F (2008) Spinal anesthesia with sequential administration of plain and hyperbaric bupivacaine provides satisfactory analgesia with hemodynamic stability in caesarean section. Int J Obstet Anesth 17:217–222

Ngan Kee WD, Lee A, Khaw KS, Ng FF, Karmakar MK, Gin T (2008) A randomized double-blinded comparison of phenylephrine and ephedrine infusion combinations to maintain blood pressure during spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery: the effects on fetal acid–base status and hemodynamic control. Anesth Analg 107:1295–1302

Ngan Kee WD, Khaw KS, Lau TK, Ng FF, Chui K, Ng KL (2008) Randomized double-blinded comparison of phenylephrine vs ephedrine for maintaining blood pressure during spinal anaesthesia for non-elective caesarean section. Anaesthesia 63:1319–1326

Zhou ZQ, Shao Q, Zeng Q, Song J, Yang JJ (2008) Lumbar wedge versus pelvic wedge in preventing hypotension following combined spinal epidural anaesthesia for caesarean delivery. Anaesth Intensive Care 36:835–839

Plint AC, Moher D, Morrison A, Schulz K, Altman DG, Hill C, Gaboury I (2006) Does the CONSORT checklist improve the quality of reports of randomized controlled trails? A systematic review. Med J Aust 185:263–267

Lee KP, Schotland M, Bacchetti P, Bero LA (2002) Association of journal quality indicators with methodological quality of clinical research articles. JAMA 287:2805–2808

Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG (1995) Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 273:408–412

Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, Egger M, Davidoff F, Elbourne D, Gotzsche PC, Lang T, CONSORT Group (2001) The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomised trials: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 134:663–694

Hollis S, Campbell F (1999) What is meant by intention to treat analysis? Survey of published randomised trials. BMJ 319:670–674

Pile K (2009) Publish or perish. Int J Rheum Dis 12:183–185

Anderson MS, Ronning EA, De Vries R, Martinson BC (2007) The perverse effects of competition on scientists’ work and relationships. Sci Eng Ethics 13:437–461

Sinha S, Sinha S, Ashby E, Jayaram R, Grocott MPW (2009) Quality of reporting in randomized trials published in high-quality surgical journals. J Am Coll Surg 209:565–571

Ioannidis JP, Evans SJ, Gotzsche PC, O’Neill RT, Altman DG, Schulz K, Moher D, CONSORT Group (2004) Better reporting of harms in randomised trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. Ann Intern Med 141:781–788

Nagurney JT, Brown DF, Sane S, Weiner JB, Wang AC, Chang Y (2005) The accuracy and completeness of data collected by prospective and retrospective methods. Acad Emerg Med 12:884–895

Hewitt C, Hahn S, Torgenson DJ, Watson J, Bland JM (2005) Adequacy and reporting of allocation concealment: review of recent trials published in four general medical journals. BMJ 330:1057–1058

Lensing AW, Prins MH, Davidson BL, Hirsh J (1995) Treatment of deep venous thrombosis with low-molecular-weight heparins. A meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 155:601–607

Doig GS, Simpson F, Delaney A (2005) A review of the true methodological of nutritional support trials conducted in the critically ill: time for improvement. Anesth Analg 100:527–533

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, CONSORT Group (2010) CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med 152:726–732

Montaigne VA, Vidal X, Aguilera C, Lahore JR (2010) Reporting randomised clinical trials of analgesics after traumatic or orthopaedic surgery is inadequate: a systematic review. BMC Clin Pharmacol 10:1–6

Halpern SH, Darani R, Douglas MJ, Wight W, Yee J (2004) Compliance with the CONSORT checklist in obstetric anaesthesia controlled trials. Int J Obstet Anesth 13:207–214

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Herdan, A., Roth, R., Grass, D. et al. Improvement of quality of reporting in randomised controlled trials to prevent hypotension after spinal anaesthesia for caesarean section. Gynecol Surg 8, 121–127 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10397-010-0648-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10397-010-0648-2