Abstract

The objective of this paper is to perform an empirical description and analysis of the duration of EU imports from the rest of the world. Toward this aim, we employ a rich data set of detailed imports to individual EU-15 countries from 140 non-EU exporters, covering the period 1962–2006. Using these data, we both perform a thorough descriptive analysis of the duration of EU trade, and test the data in a regression analysis, using discrete-time duration models with proper controls for unobserved heterogeneity. Some interesting empirical findings emerge in our analysis. First, we find that EU imports from the rest of the world are very short-lived. The median duration of EU imports is merely 1 year. Moreover, almost 60% of all spells cease during the first year of service, and less than 10% survive the first 10 years. Second, we find that short duration is a persistent characteristic of trade throughout the extended time period that we study. Third, we find a set of statistically significant determinants of the duration of trade. Among the more interesting determinants is export diversification, which—both in terms of the number of products exported and the number of markets served with the given product—substantially lowers the hazard of trade flows dying. For instance, exporting a particular product to ten rather than one EU markets increases the probability of surviving the first year of trade in any given trade relationship by as much as 31 percentage points (from 33 to 64%).

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Note that the benchmark data used by Besedeš and Prusa (2006a, b) is at the 7-digit US Tariff Schedule level, and at that level of aggregation, the median duration is 1 year. Since this paper uses the 4-digit SITC level of aggregation, to facilitate comparison, we here report the median of 2 years found by Besedeš and Prusa (2006a, b) when alternatively looking at the 4-digit SITC level of aggregation.

Note, though, that Nitsch (2009) studies the duration of German imports. We also want to point out that we look at individual EU countries’ imports from the rest of the world, but exclude intra-EU trade. The main reason for this exclusion is that changes in intra-EU trade are to a large extent driven by a very complicated integration process, the analysis of which is beyond the scope of this paper.

These results are largely confirmed by using the 10-digit (Harmonized System) US imports from 180 exporters for 1989–2001.

The former is regarded as affecting growth at the extensive margin, while the latter two at the intensive margin.

For simplicity, we will refer to the “European Union”, though, of course, this term will not be formally correct in some instances.

Since many EU-15 countries joined the European Union after 1962, we include a dummy variable in our regressions, that indicates for every year of a spell whether the respective importing country has already joined the European Union or not. It should be noted that, since Belgium and Luxembourg are treated as one trading block in the statistics, we have data for 14 importers in practice.

Since the unknown starting date of left-censored spells renders the calculation of descriptive survivor functions impossible, all left-censored observations are excluded from the data used in this section.

In this comparison, besides the differences in level of aggregation, it is important to stress that we, unlike Nitsch (2009), do not include intra-EU trade. This difference may to some extent explain the longer durations for German imports. In addition, Nitsch (2009) also studies a much shorter time period.

So, for instance, in the case of 1-year gaps, two three-year spells separated by a 1-year absence from the market will be merged into a single 7-year spell.

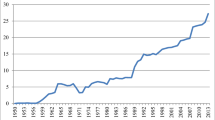

Both the importing EU countries and the exporters in the rest of the world diversify their trade quite substantially over the studied time period, both by trading new products and by entering new markets. Figures illustrating this development over time are available upon request. While we, in the interest of brevity, have chosen to only look at diversification from the importers’ and the exporters’ perspective, it is important to remember that exports (and imports) will also be diversified as soon as new trade relationships are formed. For example, countries starting to ship an “old” product to a country with which they already trade other products, but not this particular one, is also a type of diversification.

We want to make clear that we do not intend any strict causal interpretation here. It is for instance possible that large economies export many products and at the same time have long export spells, which would explain the pattern found in Fig. 3c. It is, on the other hand, also possible that firms in countries that export many products have access to more information about foreign markets which could facilitate exporting activities. The regression analysis below, where many factors can be controlled for at once, is a better tool for testing these hypotheses.

This could partly be the result of the importers in our data set being a more homogeneous group of countries than the exporters when it comes to trade.

It may be noted that likelihood-ratio tests strongly reject the null hypothesis of no latent heterogeneity for all model specifications, implying that unobserved heterogeneity plays a significant role in all model specifications and should not be ignored.

An alternative could be to include the level of per capita GDP, but the LDC dummy has the advantage of being based on a broader view of development which also takes various issues connected with economic vulnerability and human capital into account.

Nitsch (2009) includes some similar variables when studying German imports: the number of imported products from a given supplier and the number of countries exporting the same product to Germany. Using our terminology, he therefore controls for import diversification, while we—on the basis of our findings in the descriptive analysis—control for export diversification.

The economic meaning of such dummies capturing first, second, third spells, etc. is sometimes discussed in the literature. While noting that the spell number dummies in our model all have negative signs, indicating that reoccurring trade spells have lower hazards, we want to point out that interpreting these coefficients is not really appropriate here. The reason for this is that even though a specific spell may be the first observed one in the data, there is no way of telling whether or not two countries have traded a particular product prior to the first year of the observation period. Thus, an observed “first” spell may actually be of a much higher order, rendering interpretation quite difficult.

We have attempted a Hausman test to evaluate the appropriateness of a random-effects logit model versus a fixed-effects logit model. However, since the difference between the estimated covariance matrices of the fixed-effects and the random-effects estimates was not a positive definite matrix, we were unable to perform the test. This outcome is fairly common in empirical applications.

References

Baldwin, R. (1988). Hysteresis in import prices: The beachhead effect. American Economic Review, 78(4), 773–785.

Baldwin, R., & Krugman, P. (1989). Persistent trade effects of large exchange rate shocks. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 104(4), 635–654.

Bernard, A. B., & Jensen, J. B. (2004). Why some firms export. Review of Economics and Statistics, 86(2), 561–569.

Bernard, A. B., Eaton, J., Jensen, J. B., & Kortum, S. (2003). Plants and productivity in international trade. American Economic Review, 93(4), 1268–1290.

Besedeš, T. (2008). A search cost perspective on formation and duration of trade. Review of International Economics, 16(5), 835–849.

Besedeš, T. (2011). Export differentiation in transition economies. Economic Systems, 35(1), 25–44.

Besedeš, T., & Prusa, T. J. (2006a). Ins, outs and the duration of trade. Canadian Journal of Economics, 39(1), 266–295.

Besedeš, T., & Prusa, T. J. (2006b). Product differentiation and duration of US import trade. Journal of International Economics, 70(2), 339–358.

Besedeš, T., & Prusa, T. J. (2010). The role of extensive and intensive margins and export growth. Journal of Development Economics. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2010.08.013.

Brenton, P., Pierola, M. D., & von Uexküll, E. (2009a). The life and death of trade flows: Understanding the survival rates of developing-country exporters. In R. Newfarmer, W. Shaw, & P. Walkenhorst (Eds.), Breaking Into new markets: Emerging lessons for export diversification (pp. 127–144). Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

Brenton, P., Saborowski, C., & von Uexküll, E. (2009b). What explains the low survival rate of developing country export flows (Policy Research Working Paper No. 4951). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Cadot, O., Iacovone, L., Pierola, D., & Rauch, F. (2011). Success and failure of African exporters F.R.E.I.T. (Working Paper No. 282). Forum for Research in Empirical International Trade.

Clerides, S. K., Lach, S., & Tybout, J. R. (1998). Is learning by exporting important? Micro-dynamic evidence from Colombia, Mexico and Morocco. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 113(3), 903–947.

Cox, D. R. (1972). Regression models and life-tables (with discussion). Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B, 34(2), 187–220.

Cox, D. R., & Oakes, D. (1984). Analysis of survival data. London: Chapman & Hall/CRC.

Dixit, A. (1989). Hysteresis, import penetration, and exchange rate pass-through. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 104(2), 205–228.

Feenstra, R. C. (1997). U.S. exports, 1972–1994: With state exports and other U.S. data (NBER Working Paper No. 5990). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Fugazza, M., & Molina, A. C. (2009). The determinants of trade survival. (HEID Working Paper No 05/2009). Geneva: The Graduate Institute.

Greenaway, D., & Kneller, R. (2007). Firm heterogeneity, exporting and foreign direct investment. Economic Journal, 117(517), F134–F161.

Greenaway, D., & Kneller, R. (2008). Exporting, productivity and agglomeration. European Economic Review, 52(5), 919–939.

Helpman, E., Melitz, M., & Rubinstein, Y. (2008). Estimating trade flows: Trading partners and trading volumes. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(2), 441–487.

Hess, W., & Persson, M. (2010). The duration of trade revisited. Continuous-time vs. discrete-time hazards (Working Paper 2010:1), Department of Economics, Lund University.

Jenkins, S. P. (1995). Easy estimation methods for discrete-time duration models. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 57(1), 129–137.

Kalbfleisch, J. D., & Prentice, R. L. (1980). The statistical analysis of failure time data. New York: Wiley.

Kaplan, E. L., & Meier, P. (1958). Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 53(282), 457–481.

Martins, P. S., & Yang, Y. (2009). The impact of exporting on firm productivity: A meta-analysis of the learning-by-exporting hypothesis. Review of World Economics/Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 145(3), 431–445.

McCall, B. P. (1994). Testing the proportional hazards assumption in the presence of unmeasured heterogeneity. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 9, 321–334.

Melitz, M. J. (2003). The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica, 71(6), 1695–1725.

Nitsch, V. (2009). Die another day: Duration in German import trade. Review of World Economics/Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 145(1), 133–154.

Rauch, J. E. (1999). Networks versus markets in international trade. Journal of International Economics, 48(1), 7–35.

Rauch, J. E., & Watson, J. (2003). Starting small in an unfamiliar environment. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 21(7), 1021–1042.

Roberts, M. J., & Tybout, J. R. (1997). The decision to export in Colombia: An empirical model of entry with sunk costs. American Economic Review, 87(4), 545–564.

Santos Silva, J. M. C., & Tenreyro, S. (2006). The log of gravity. Review of Economics and Statistics, 88(4), 641–658.

Sueyoshi, G. T. (1995). A class of binary response models for grouped duration data. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 10(4), 411–431.

van den Berg, G. J. (2001). Duration models: Specification, identification, and multiple durations. In J. J. Heckman, & E. Leamer (Eds.), Handbook of Econometrics, vol. 5 (pp. 3381–3460). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Vernon, R. (1966). International investment and international trade in the product cycle. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 80(2), 190–207.

Volpe-Martincus, C., & Carballo, J. (2008). Survival of new exporters in developing countries: Does it matter how they diversify?. Globalization, Competitivesness and Governability, 2(3), 30–49.

Wagner, J. (2007). Exports and productivity: A survey of the evidence from firm-level data. World Economy, 30(1), 60–82.

Yeaple, S. R. (2005). A simple model with firm heterogeneity, international trade, and wages. Journal of International Economics, 65(1), 1–20.

Acknowledgments

This paper builds on the empirical part of Working Paper 2009:12, Department of Economics, Lund University, which was presented at the 2009 ETSG Conference in Rome and at seminars at Lund University and IFN in Stockholm. We are very grateful to two anonymous referees for their constructive comments. We would also like to thank conference and seminar participants, and in particular Yves Bourdet, Joakim Gullstrand, Scott Hacker, Magnus Henrekson, Fredrik Sjöholm, and Fredrik Wilhelmsson for many valuable comments. We are very grateful to Paul Linge and the LUNARC team for providing us access to very powerful computing resources. Financial support from the Jan Wallander and Tom Hedelius Foundation under research grant numbers P2006-0131:1, P2009-0189:1 and W2009-0352:1, and from the Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg Foundation is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Hess, W., Persson, M. Exploring the duration of EU imports. Rev World Econ 147, 665–692 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-011-0106-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-011-0106-x