Abstract

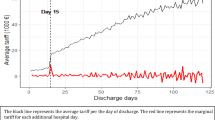

In several countries, a fee has been introduced to reduce bed-blocking in hospitals. This paper studies the implications of this fee for the strategic decisions of the hospitals and the long-term care providers. We introduce a Stackelberg game where the hospital is the leader and the care provider the follower. The policy reduces the treatment time at the hospital but does not necessarily lead to less bed-blocking, as this depends on the treatment time and bed-blocking before the reform. We test the results with data from the Norwegian Coordination Reform introduced in 2012 and find that this reform led to a large reduction in bed-blocking. The direct effect was even larger than a naïve comparison would suggest because hospitals began to report patients as ready to be discharged earlier than before the reform. Confronted with the theoretical predictions, this would mean that hospital services in average were set relatively close to the minimum levels before the reform.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

There is, of course, also a lower limit to the need for hospital services, defined by the health level necessary to live.

In this specification, the utility functions are linear in income. This assumption is quite standard at the institutional level, because in models of risk, risk neutrality is usually assumed at this level.

Note that in the utility function of the hospital, the health of other patients, i.e., patients not receiving care services, are not taken into account. Thus, we assume that there is no trade-off in treatment between regular patients and patients in need of municipal care services after discharge. However, bed-blocking affects the financial situation of the hospital in general.

Activity-based funding for hospitals is not explicitly taken into account, see "Empirical analysis" below. However, the unit cost can be thought of as the cost net of activity-based payments.

Note that if the hospital discharges the patient at health level h2, there is no health impact from letting the patient stay at the hospital after discharge. The only reasons for this are financial incentives or capacity constraints at the care provider.

For example, Norway has a Municipal Health and Care Services Act that ensures that the municipalities’ services offered are sound, for example that they have to be comprehensive and coordinated (§ 4–1).

In Eq. (7), we assume for simplicity that hospital and care services can be measured in the same units. Alternatively, we could introduce a parameter as an exchange value, but this would not change the qualitative results.

The second order condition is \(u_{{}}^{C^{\prime\prime}} (h_{x}^{^{\prime}} - h_{y}^{^{\prime}} )^{2} + u_{{}}^{C^{\prime}} \left( {h_{x,x}^{^{\prime\prime}} + h_{y,y}^{^{\prime\prime}} - h_{x,y}^{^{\prime\prime}} - h_{y,x}^{^{\prime\prime}} } \right) \equiv A\). A < 0 does not necessarily follow as \(h_{x,y}^{^{\prime\prime}} < 0\), but holds if an interior solution exists.

Note that this is the case in Norway, as the fee is set to cover the costs of a day at the hospital. These costs are in most cases much higher than the costs of care services in the municipalities, such as in a nursing home.

If we replaced Eq. (5) with \(x = \overline{x} + \sigma b,{\kern 1pt} \,{\kern 1pt} 1 < \sigma < 0\), treatment and bed-blocking would be imperfect substituites, and the treatment time would fall, but not necessary to the minimum level. If they are imperfect subsitutes, the hospital does not provide the same service when patients are bed-blocking.

We return to this at the end of this subsection.

Note that the Figures are identical apart from the initial choice of \(\overline{x}\).

2020 exchange rate.

This financial incentive did not have any effect on specialist somatic health care services including hospitalization, according to Askildsen et al. [1].

The fee has been adjusted annually and was NOK 5,036 in 2020, i.e., approximately € 480.

In 2012, NOK 560 million (around € 53 million) was transferred from hospital budgets to municipalities so that municipalities could offer suitable care to patients after discharge from hospital. Note that this was only part of the budget transfer from hospitals to municipalities, because the other part of the reform also involved transfers (https://www.regjeringen.no/no/tema/helse-og-omsorg/helse--og-omsorgstjenester-i-kommunene/samhandlingsreformen-i-kortversjon1/id650137/).

According to the Office of the Auditor General of Norway [24], these emergency care units were not used very much, and several municipalities used them as part of their ordinary care service. Swanson et al. [27] found that the introduction of these care units reduced hospitalization of patients above 80 years old by barely 2%.

Differences between symbolic and high fees are also studied in Brekke et al. [3], where a small fee for avoiding contributing to a public good is found to stress the responsibility of the individual, while a large fee allows the individual to move the responsibility to the regulating authority because it may now be able to buy the good elsewhere.

References

Askildsen, J.E., Holmås, T.H., Kaarbøe, O., Monstad, K.: Evaluering av kommunal medfinansiering. Tidsskrift for omsorgsforskning 2(2), 135–142 (2016)

Bouttell, J., Craig, P., Lewsey, J., Robinson, M., Popham, F.: Synthetic control methodology as a tool for evaluating population-level health interventions. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 72, 673–678 (2018)

Brekke, K.A., Kverndokk, S., Nyborg, K.: An Economic Model of Moral Motivation. J. Public Econ. 87(9–10), 1967–1983 (2003)

Bryan, K.: Policies for reducing delayed discharge from hospital. Br. Med. Bull. 95(1), 33–46 (2010)

Colmorten, E., Clausen, T., Bengtsson, S.: Providing integrated health and social care for older persons in Denmark, Chapter 4 In: Leichsenring K, Alaszewski AM (eds) Providing Integrated Health and Social Care for Older Persons - A European Overview of Issues at Stake, Routledge (2004)

Deb, P., Norton, E.C., Manning, W.G.: Health econometrics using Stata. Stata Press, College Station, TX (2017)

Forder, J.: Long-term care and hospital utilisation by older people: an analysis of substitution rates. Health Econ. 18(11), 1322–1338 (2009)

Gaughan, J., Gravelle, H., Siciliani, L.: Testing the bed-blocking hypothesis: does nursing and care home supply reduce delayed hospital discharges? Health Econ. 24(Suppl. 1), 32–44 (2015)

Gaughan, J., Gravelle, H., Santos, R., Siciliani, L.: Long-term care provision, hospital bed blocking, and discharge destination for hip fracture and stroke patients. Int. J. Health Econ. Manag. 17, 311–331 (2017)

Glasby, J., Littlechild, R., Pryce, K.: Show me the way to go home: a narrative review of the literature on delayed hospital discharges and older people. Br. J. Soc. Work. 34(8), 1189–1197 (2004)

Glasby, J., Littlechild, R., Pryce, K.: All dressed up but nowhere to go? Delayed hospital discharges and older people. J Health Serv. Res. Policy 11(1), 52–58 (2006)

Gneezy, U., Rustichini, A.: A fine is a price. J. Leg. Stud. 29(1), 1–17 (2000)

Gneezy, U., Rustichini, A.: Pay enough or don’t pay at all. Quart. J. Econ. 115(3), 791–810 (2000)

Godden, S., McCoy, D., Pollock, A.M.: Policy on the rebound: trends and causes of delayed discharges in the NHS. J. R. Soc. Med. 102(1), 22–28 (2009)

Grimsmo, A., Magnussen, J.:Norsk samhandlingsreform i et internasjonalt perspektiv, Report to the Research Council of Norway (2015).

Holmås, T.H., Kjerstad, E., Lurås, H., Straume, O.R.: Does monetary punishment crowd out pro-social motivation? A natural experiment on hospital length of stay. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 75(2), 261–267 (2010)

Jones, A. M., Rice, N., Bago d'Uva, T. Balia, S.: Applied health economics. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, Abingdon, United Kingdom (2013).

Kümpel, C.: Do financial incentives influence the hospitalization rate of nursing home residents? Evidence from Germany. Health Econ. 28, 1235–1247 (2019)

Lin, C.-c, Yang, C.C.: Fine enough or don’t fine at all. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 59, 195–213 (2006)

Manzano-Santaella, A.: Disentangling the impact of multiple innovations to reduce delayed hospital discharges. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 15(1), 41–46 (2010)

McCoy, D., Godden, S., Pollock, A.M., Bianchessi, C.: Carrot and sticks? The Community Care Act (2003) and the effect of financial incentives on delays in discharge from hospitals in England. J. Public Health 29(3), 281–287 (2007)

Melberg, H.O., Hagen, T.P.: Liggetider og reinnleggelser i somatiske sykehus før og etter Samhandligsreformen. Tidsskrift for omsorgsforskning 2(2), 143–158 (2016)

Mur-Veeman, I., Govers, M.: Buffer management to solve bed-blocking in the Netherlands 2000–2010. Cooperation from an integrated care chain perspective as a key success factor for managing patient flows. Int. J. Integr. Care 11(Special 10th Anniversary Edition), e080 (2011)

Riksrevisjonen: Riksrevisjonens undersøkelse av ressursutnyttelse og kvalitet i helsetjenesten etter innføringen av samhandlingsreformen, Dokument 3:5 (2015–2016) (2016).

Rubin, S.G., Davies, G.H.: Bed blocking by elderly patients in general-hospital wards. Age Ageing 4, 142–147 (1975)

Styrborn, K., Thorslund, M.: “Bed-blockers”: delayed discharge of hospital patients in a nationwide perspective in Sweden. Health Policy 26, 155–170 (1993)

Swanson, J., Alexandersen, N., Hagen, T.P.: Førte opprettelsen av kommunale øyeblikkelig hjelp døgnenheter til færre innleggelser for eldre pasienter ved somatiske sykehus? Tidsskrift for omsorgsforskning 2(2), 125–134 (2016)

Zychlinski, N., Mandelbaum, A., Momčilović, P., Cohen, I.: Bed blocking in hospitals due to scarce capacity in geriatric institutions—cost minimization via fluid models. Manuf. Serv. Op. Manag. 22(2), 223–428, C2 (2020)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This paper is part of the project “Evaluation of the Coordination Reform” funded by the Research Council of Norway. Kverndokk also received funding from the project “Incentives, Efficiency and Quality of Care in Long-Term Care for the Elderly” also funded by the Research Council of Norway. We are indebted to comments from Lone Grønbæk, Michael Hoel, Tor Iversen, Andreas Kotsadam, Albert Ma, Eric Nævdal, Aleksandr Proskin, Lise Rochaix, other participants in the project, and seminar participants at HERO, Frisch Centre, NMBU, Bergen University College, University of Southern Denmark, the Norwegian National Health Economics Conference, and EHEW 2017.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kverndokk, S., Melberg, H.O. Using fees to reduce bed-blocking: a game between hospitals and long-term care providers. Eur J Health Econ 22, 931–949 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-021-01299-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-021-01299-9