Abstract

The new disease outbreak that causes atypical pneumonia named COVID-19, which started in China’s Wuhan province, has quickly spread to a pandemic. Although the imaging test of choice for the initial study is plain chest radiograph, CT has proven useful in characterizing better the complications associated with this new infection. We describe the evolution of 3 patients presenting pneumomediastinum and spontaneous pneumothorax as a very rare complication of COVID-19 and their particular interest as a probable prognostic factor.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In December 2019, the outbreak of a new infection that produced cases of atypical pneumonia and severe acute respiratory syndrome was described. This outbreak was later related to an emerging virus from the Coronaviridae family, whose initial focus was located in China’s Wuhan province. The virus, identified in January 2020 as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) causing the disease COVID-19, has spread rapidly around the world causing more than 6.3 million infections and more than 370,000 reported deaths [1].

In Spain, the first confirmed case of COVID-19 disease was reported on January 31, 2020, with the Comunidad de Madrid being the most affected by it. Initially, chest radiograph was the imaging technique used in our hospital as an effective diagnostic tool in the emergency department. Subsequently, the implementation of a second computerized tomography (CT) equipment has made it possible to carry out a greater number of thoracic CT studies, facilitating the early identification of COVID-19 pneumonia and its complications, including the most common thrombotic or inflammatory phenomena, in order to provide timely treatment. We reported three cases of spontaneous pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax characterized by CT as a rare complication of COVID-19 pneumonia.

Case report

Case 1

An 84-year-old woman with a history of anticoagulation with acenocoumarol due to prosthetic valve replacement, renal failure on replacement therapy with hemodialysis, stage C heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia pharmacologically controlled went to the emergency department with head trauma following a fall at her home; so a head CT was performed, finding an acute subdural hematoma.

During her stay, low oxygen saturation was observed and a simple chest radiograph was performed in two projections, PA (posteroanterior) and lateral, where radiological findings suggestive of lung involvement by COVID-19 were observed. An extension study was performed with genomic amplification to confirm that the diagnosis was negative. It was repeated for a second time, being negative again, so she was discharge. Five days later, she consulted again presenting dyspnea, fever, and cough. The chest X-ray showed bronchopneumonia and the PCR (polymerase chain reaction) was positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection, so she was admitted for hospital management (CURB 65 of 1). Management included pharmacological treatment with hydroxychloroquine, ceftriaxone, and methylprednisolone, as well as oxygen supplementation by reservoir with 50% FiO2. During her hospitalization, she presented progressive deterioration of respiratory function with dyspnea despite oxygen therapy, showing atelectasis of the left lung until developing a white lung that was objectifiable in serial chest radiograph studies in the anteroposterior view. It was decided to perform a chest CT with IVC (intravenous contrast) for a better characterization.

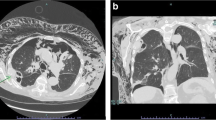

On the chest CT, right partial hydropneumothorax, left full hydropneumothorax, and pneumomediastinum were identified, as well as pulmonary involvement by COVID-19 (Fig. 1). The patient presented an unsatisfactory clinical evolution and died 18 days after the symptoms began.

a Axial slide in lung window, evidence of a bilateral pneumothorax chamber (green arrows), and pneumomediastinum (red arrows). b Coronal MPR reconstruction in lung window, with the right pneumothorax chamber, as well as the presence of air in the mediastinum in the ascending thoracic aorta and surrounding the cardiac silhouette. Observe the GGO (ground-glass opacities) in the visible lung parenchyma typical of COVID-19 involvement

Case 2

A 67-year-old male patient who consulted with 5 days of fever and dyspnea, on antibiotic treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanate for bacterial pharyngotonsillitis suspected in primary care. On admission, his vital signs were stable, presenting an oxygen saturation of 94% with a mask with FiO2 of 50%, for which he was treated as a suspect for COVID-19. As initial imaging test, he underwent a chest X-ray with PA and lateral projections, where bilateral opacities with multilobar affectation suggestive of moderate involvement by COVID-19 were observed. In addition, a pneumothorax chamber and radiolucent lines were identified in both projections surrounding the cardiomediastinal contour compatible with pneumomediastinum (Fig. 2). Given the findings, it was decided to complement the study with a chest CT without contrast to characterize the extension of the pneumomediastinum (Fig. 3).

Coronal reconstruction in the lung window (image a), a chamber of bilateral apical partial pneumothorax (red), pneumomediastinum surrounding the great vessels, and cardiac silhouette (green) and pneumorachis (black arrow) were identified. Axial section of CT of the chest (image b), with extensive lung affectation of ground-glass attenuation and thickening of septa (crazy paving), predominantly bibasal

Due to the increased oxygen requirement and respiratory work, as well as the severity of the evolution of the disease, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit in treatment with piperacillin/tazobactam and azithromycin. A pleural drainage tube was inserted to control the pneumothorax, showing clinical improvement. In the following radiographic controls, reabsorption of the pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax were observed. However, the patient clinically presented progressive deterioration with decreased renal function, worsening respiratory function, and hemodynamic instability. Despite the support measures and the intra-hospital management, the patient developed multiple organ failure and passed 18 days after the symptoms initiated.

Case 3

A 73-year-old male patient with a history of basal cell epithelioma, obstructive sleep apnea, obesity, and depression under pharmacological treatment, presented with a 5-day clinical course of fever and dyspnea, was admitted to study a respiratory infection, and a chest X-ray was performed in PA and lateral projections, showing alveolar opacity with a bibasal air bronchogram, therefore the suspected diagnosis was moderate severity COVID-19 pneumonia (CURB65 of 2). The genomic amplification test for SARS-CoV-2 was positive, and he started pharmacological treatment with hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, tocilizumab, methylprednisolone, and oxygen support with a mask with a reservoir at 15 l/min (FiO2 of 90%). Given the torpid evolution of the disease, it was decided to perform a chest CT with contrast, suspecting pulmonary thromboembolism.

In the study, filling defects were identified in the segmental arteries of both upper lobes, extensive bilateral involvement by coronavirus, and, as an incidental finding, a minimal chamber of pneumomediastinum (Fig. 4). Anticoagulant therapy and non-invasive ventilatory support with CPAP were started. The patient presented progressive deterioration until his death 15 days after admission.

Chest CT scan with iodinated contrast to study the pulmonary arteries. Coronal reconstruction (image a) after maximum intensity projection post-processing (MIP), where filling defects are observed in the segmental branches of the superior lobar arteries (white). Sagittal MPR reconstruction (image b) and a minimal pneumomediastinum chamber is identified (blue arrow). Axial CT slice (image c), with extensive bilateral parenchymal involvement showing areas of ground-glass opacities and bibasal consolidation (stars)

Discussion

Chest CT is a quick and relatively easy-to-access study for characterization of lung lesions caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Among the most characteristic findings are ground-glass opacities, consolidated opacities, and septa thickening. These cases illustrate the severity of the disease associated with a rare complication such as pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum in this case of spontaneous origin [2].

Although the development of the pneumothorax chamber is usually secondary to barotrauma in patients in the intensive care unit in most cases, our patients did not require, at diagnosis, assisted mechanical ventilation. Therefore, the mechanism of the injury, although not fully understood, may be secondary to alveolar damage from the infection and a rupture of the alveolar wall due to increased pressure from pronounced coughing that occurs in response to the virus. Pneumomediastinum may be due to air leakage through the interstitial space due to increased pressure [3].

It should be emphasized that patients did not have a history of smoking or clear parenchymal patterns that suggest bullae or emphysema that could be predisposing factors for the development of pneumothorax.

In conclusion, when reporting these findings in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia, emphasis is placed on the usefulness of chest CT to rule out thromboembolic complications or, in patients with progressive worsening of respiratory function, spontaneous pneumothorax associated with pneumomediastinum. Given that these patients have ended in a torpid evolution with fatal outcome in all three cases, it cannot be excluded that the presence of pneumothorax and/or pneumomediastinum may be associated with more severity and worse outcome; more studies with a bigger number of cases are required to assess causality or association [4].

References

Dong E, Du H, Gardner L (2020) An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis 3099(20):19–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1

Sun R, Liu H, Wang X (2020) Mediastinal emphysema, giant bulla, and pneumothorax developed during the course of COVID-19 pneumonia. Korean J Radiol 21:1–4

Park SJ, Park JY, Jung J, Park SY (2016) Clinical manifestations of spontaneous pneumomediastinum. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 49(4):287–291

Zhou C, Gao C, Xie Y, Xu M (2020) COVID-19 with spontaneous pneumomediastinum. Lancet Infect Dis 20(4):510. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30156-0

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

López Vega, J.M., Parra Gordo, M.L., Diez Tascón, A. et al. Pneumomediastinum and spontaneous pneumothorax as an extrapulmonary complication of COVID-19 disease. Emerg Radiol 27, 727–730 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10140-020-01806-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10140-020-01806-0