Abstract

Background

Microsatellite instability (MSI) has been observed in 8–39 % of sporadic gastric cancers. However, despite numerous reports indicating a significant relationship between intestinal-type histology and MSI, detailed correlation between histological subtypes and MSI remains obscure. The purpose of the present study is to clarify the relationship between histological subtype and microsatellite status in gastric carcinomas.

Methods

Microsatellite status was examined for 464 consecutive gastric carcinomas from 420 patients as well as histological subtypes and other clinicopathological findings.

Results

MSI was observed in 82 carcinomas (17.7 %), and the greatest proportions were observed in solid-type, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (43.0 %) and papillary adenocarcinoma (32.5 %), both being significantly higher than those of other subtypes. The proportion increased with advancing age (0 % at 51–64 years, 8.5 % at 65–74 years, 18.4 % at 75–84 years, 35.3 % at 85–96 years). Compared with microsatellite-stable carcinomas, microsatellite-unstable carcinomas were significantly related with older age, female gender, antral location, and predominant papillary adenocarcinoma and solid-type, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. Poorly differentiated type carcinoma was significantly less frequent than differentiated type in microsatellite-unstable cancer at the early stage, whereas no significant difference existed at the advanced stage.

Conclusions

These results suggest that there are specific histological subtypes with highly frequent MSI and that gastric carcinoma with MSI originates from differentiated-type carcinomas, indicating histological diversity during tumor growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

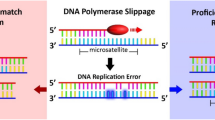

Microsatellite instability (MSI) is a hallmark of DNA mismatch repair deficiency, which is one of the pathways of gastric carcinogenesis. MSI has been observed in 8–39 % of gastric carcinomas [1–6]. Microsatellite-unstable gastric carcinomas have the following clinicopathological features: older age, expanding growth pattern, antral location, intestinal-type histology, a lower incidence of lymph node metastasis, and favorable prognosis. Regarding molecular mechanism, age-related hypermethylation in the hMLH1 promoter is closely associated with the development of sporadic gastric carcinomas with MSI [7, 8].

Predominant intestinal-type histology in microsatellite-unstable gastric carcinomas was widely accepted [2, 4, 5, 9, 10]. However, several issues remain poorly defined and are the subject of much debate because of several reports showing predominant poorly differentiated histology [1] or no significant association between histological morphology and MSI [6, 11–13]. Because most previous reports were not concerned with histological subtype, but rather with Lauren’s classification, a relationship between the histological subtypes of gastric carcinomas and MSI remains obscure. The aim of the present study is to clarify the relationship between the histological subtypes of gastric carcinomas and microsatellite status and to examine histological diversity associated with MSI.

Materials and methods

Patients

We selected 420 consecutive patients with 464 gastric carcinomas from cases in the Tokyo Metropolitan Geriatric Hospital between 2000 and 2008. The patients included 223 men and 197 women with a median age of 78 years (range 51–96 years). Patients with Lynch syndrome were excluded in this study. Three hundred eighty-four patients had single carcinoma, 28 had double carcinomas, and 8 had triple carcinomas. Pathological examination and medical research were performed with informed written consent by the patients, and this work was approved by the ethics committee of the Tokyo Metropolitan Geriatric Hospital.

Histopathological evaluation

All tissue samples were fixed with 10 % formalin after resection and then embedded in paraffin according to the standard procedure. Serial sections, 3- and 10-μm thick, were prepared for each specimen. The 3-μm-thick sections were used for hematoxylin and eosin staining, and the 10-μm-thick sections were used for DNA extraction. Four hundred sixty-four cases of gastric carcinoma were pathologically diagnosed according to the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma (details shown in Fig. 1) [14]. Gastric carcinomas were also divided into three groups according to the modified Nakamura classification: differentiated type, undifferentiated type, and mixed type [15]. The differentiated and undifferentiated types are almost equivalent to the intestinal and diffuse types in Lauren’s classification. Carcinomas in which different types were present in an area of more than 10 % were classified as mixed type. According to the depth of invasion, gastric carcinomas were divided into two groups: early-stage cancers (pT1) and advanced cancers (pT2–4) [14]. Lymph node metastasis was described according to the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma, which was the same as the 7th version of the TNM classification [16].

Representative histology of six subtypes of gastric carcinoma according to the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma: a well-differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma (tub1); b moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma (tub2); c papillary adenocarcinoma (pap); d solid-type, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (por1); e non-solid-type, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (por2); f signet-ring cell carcinoma (sig). Upper row: three subtypes (tub1, tub2, and pap) are classified as differentiated type; lower row: three subtypes (por1, por2, and sig) as undifferentiated type. Mucinous carcinoma is classified as differentiated or undifferentiated type according to its histological component

DNA extraction

One 10-μm section placed on a glass slide was used for the representative portion of each sample. The tissues were scraped from the semidried section with a blade under the stereomicroscope. DNA was extracted separately from the tumor and normal areas. The sample was incubated overnight at 56 °C in lysis buffer (0.5 % Tween 20, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM, Tris–HCl pH 8.0) with 1 μg/μl proteinase K. DNA was extracted from all these samples by a phenol–chloroform procedure.

Microsatellite instability

We screened microsatellite status using the mononucleotide repeats BAT25 and BAT26 according to protocols described by other investigators [17–19]. These probes are sensitive and recommended for the detection of microsatellite-unstable tumors, especially in cases of high-frequency MSI in gastric carcinoma as well as colorectal carcinoma [20, 21]. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) conditions were as follows for both markers: 50 nM KCl, 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.3, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.5 mM each primer, 0.4 U Taq polymerase (Takara, Kyoto, Japan), and 1 μl DNA solution. Amplifications were performed in a thermal cycler for 35 cycles in conditions described by other investigators [22]. The PCR products were mixed with an equal volume of loading buffer (95 % formamide, 0.05 % bromophenol blue, 25 mM EDTA), then electrophoresed on denaturing 6 % polyacrylamide gels at 50 °C, and stained with silver stain kit (Atto, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer. Cases in which bands of different molecular weights were observed in the tumor DNA in either marker, but were not observed in normal DNA, were designated as microsatellite unstable.

Survival analysis

Two hundred thirty-three patients were available for survival analysis. Cancer-specific survival rates were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and rates were compared by the log-rank test.

Statistical analysis

All data were subjected to statistical analysis using StatView 5.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Comparisons among continuous and categorical variables were made using the Mann–Whitney test, chi-square test, or Fisher’s exact probability test. A P value of less than 0.05 (two sided) was considered significant.

Results

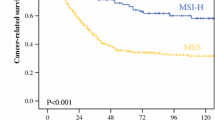

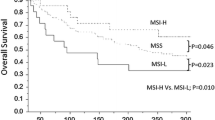

MSI was observed in 82 (17.7 %) of 464 carcinomas. Of 82 carcinomas, 63 tumors (76.8 %) were positive for both BAT25 and BAT26 instability, 5 tumors (6.1 %) only for BAT25 instability, and 14 tumors (17.1 %) only for BAT26 instability. Although there was no significant change, the proportion of MSI increased with the number of carcinomas in the stomach (Table 1). MSI of differentiated and undifferentiated types accounted for 15.5 % (47/303) and 21.7 % (35/161), respectively, with no significant difference being detected between the two types (P = 0.09). The most frequent MSI was observed in solid-type, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (43.0 %, 34/79), followed by papillary adenocarcinoma (32.5 %, 13/40) (Table 2). The proportion of MSI in each histological subtype of early and advanced gastric carcinomas is shown in Table 3. MSI was most frequently found in papillary adenocarcinomas at early stages and solid-type, poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas at advanced stages (Table 3). The proportion of MSI increased with advancing age (0 % at 51–64 years, 8.5 % at 65–74 years, 18.4 % at 75–84 years, and 35.3 % at 85–96 years) (Fig. 2). The proportion of MSI in women (27.1 %) was significantly higher than that in men (9.6 %; P < 0.001). Compared with microsatellite-stable carcinomas, microsatellite-unstable carcinomas were significantly related with older age, female gender, occurrence at a lower location, and predominant papillary adenocarcinoma and solid-type, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (Table 4). Gastric carcinomas with MSI showed significantly less frequent lymph node metastases at advanced stages (Table 4). There was no significant difference in cancer-specific survival rates between microsatellite-unstable and microsatellite-stable gastric carcinomas in overall, stage I, stage III, and stage IV (Fig. 3). In stage II, however, the microsatellite-stable group showed better prognosis in comparison with the microsatellite-unstable group (Fig. 3c, P = 0.014).

Age-related alterations of the proportion (graphed line) of microsatellite instability (MSI). The proportion of MSI increases with age (8.5 % at 65–74 years, 18.4 % at 75–84 years, 35.3 % at 85–96 years; P < 0.01). The proportion of MSI in women (27.1 %) was significantly higher than that in men (9.6 %; P < 0.0001). Closed rectangles men; open rectangles women. The proportions of papillary and solid-type, poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas in MSI-positive tumors are 66.7 % (8/12) at 65–74 years, 60 % (24/40) at 75–84 years, and 50 % (15/30) at 85–96 years

Kaplan–Meier analysis of cancer-specific survival in patients with microsatellite-unstable (MSI) and microsatellite-stable (MSS) gastric carcinomas. There is no significant difference in cancer-specific survival rates between microsatellite-unstable (MSI) and microsatellite-stable (MSS) gastric carcinomas in overall (a), stage I (b), stage III (d), and stage IV (e), although microsatellite-stable carcinomas show significantly better prognosis (P = 0.014) in stage II (c)

In early-stage cancers, the undifferentiated type was significantly less frequent than the differentiated and mixed types in microsatellite-unstable carcinomas (P = 0.02), whereas no significant difference existed at advanced stages (Table 5), indicating that adenocarcinomas without a glandular component are significantly less frequent in early stages of microsatellite-unstable gastric carcinomas.

Discussion

We have shown frequent MSI in papillary and solid-type, poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas among gastric carcinomas. Additionally, microsatellite-unstable gastric carcinomas show specific correlations with age, gender, tumor location, less-frequent undifferentiated-type carcinoma at early stages, and lower incidence of lymph node metastasis at the advanced stage.

The present study demonstrates no significant difference in the proportion of MSI between the differentiated type and the undifferentiated type. Although predominant intestinal-type histology in microsatellite-unstable carcinomas has been widely accepted [2, 4, 5, 9, 10, 23], several reports have shown predominant poorly differentiated histology [1], or no significant association between histological morphology and MSI [6, 11–13]. The differences among these reports were considered to depend upon the specific groups of cases studied and the type and number of markers examined. As we demonstrate here, however, the proportion of MSI is significantly correlated with histological subtype, such as papillary and solid-type, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. Thus, it is likely that a comparison of the proportions of MSI between the differentiated type, including papillary adenocarcinoma, and the undifferentiated type, including solid-type carcinoma, is less meaningful. More useful comparisons among carcinoma subtypes should be made according to other tumor properties that take into account different pathways of gastric carcinogenesis.

More than one third of papillary and solid-type, poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas showed MSI in elderly patients with gastric carcinomas. High proportions (26–40 %) of MSI have been reported in papillary carcinoma [8, 24]. Papillary or papillotubular adenocarcinoma is proposed to be a distinct morphological type with a molecular pathway of MSI because microsatellite-unstable papillary carcinoma has been found to exhibit preferential hypermethylation of the hMLH1 promoter, with absence of hMLH1 expression, and frequent mutations in genes such as BAX, TGFβRII, MSH3, and MSH6 [8]. The papillary or papillotubular type of early gastric carcinoma also showed centromere numerical abnormality [25]. On the other hand, few reports have mentioned the proportion of MSI in solid-type poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas. Although a few reports have demonstrated a high proportion (64 %) in poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas [1], to our best knowledge, this is the first report to demonstrate that the greatest frequency of MSI occurs in solid-type carcinomas. Recent molecular studies have also demonstrated that solid-type gastric cancers have different genetic profiles from those of other poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas [23]. In poorly differentiated gastric carcinomas, solid-type carcinoma is believed to be a different entity from non-solid-type and signet-ring cell carcinomas. Therefore, both papillary and solid-type, poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas are peculiar histological subtypes that show different characteristics from those of other types, such as tubular adenocarcinoma and signet-ring cell carcinoma.

MSI-positive gastric carcinomas were also found to correlate with age, gender, and tumor location. Several reports, together with our results, have demonstrated that microsatellite-unstable gastric carcinomas are significantly associated with the elderly [2, 4–6], women [3, 5], and antral location [2, 4, 5, 9]. These characteristics are similar to those of medullary-type, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the colorectum, which is a representative MSI-positive carcinoma showing predominant occurrence in older age, women, and the proximal colon [26]. Medullary-type colorectal carcinoma shows hypermethylation of the hMLH1 promoter with loss of hMLH1 expression [26]. As already mentioned, papillary adenocarcinoma of the stomach has the same features [8]. Therefore, this evidence suggests that gastrointestinal carcinomas with MSI predominantly occur at a specific site within each organ in elderly women.

Microsatellite-unstable gastric carcinoma shares histological and molecular features with those occurring in Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-associated carcinoma: moderately differentiated or poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with lymphocyte infiltration and hypermethylation of the gene promoter. Age-related MSI-positive gastric carcinoma showed a strong relationship with hMLH1 methylation with absent hMLH1 expression [7], showing characteristic features such as older age, female predominance, and antral location. On the other hand, EBV-associated gastric carcinoma has a relationship with hypermethylation of the promoter region of various genes. In EBV-associated carcinoma, however, CpG islands in the hMLH1 promoter region are not frequently hypermethylated, resulting in a low proportion of MSI. Moreover, EBV-associated gastric cancers preferentially occur in the cardia or body of the stomach in relatively younger patients with male predominance [27]. Thus, these data suggested that despite the presence of common features, two kinds of tumors occur in the development of different carcinogenesis and show different disease entities from each other.

The present study demonstrates that almost all early gastric carcinomas with MSI are of the differentiated type, whereas the undifferentiated-type component appears primarily in advanced stages. In other words, gastric carcinoma with MSI develops principally as a differentiated-type tumor that then progresses to a more poorly differentiated tumor over time. This phenomenon raises the question of whether MSI-positive papillary adenocarcinoma at early stages is related to solid-type, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma at advanced stages. Adachi et al. reported that papillotubular differentiation in the mucosa of tumor margins was seen in 38 % of poorly differentiated medullary carcinomas and hypothesized that medullary-type carcinomas arise as papillary adenocarcinomas in the gastric mucosa and then become solid or medullary after tumor invasion through the gastric wall [28]. The evidence that both papillary and solid-type adenocarcinomas show similar biological behavior, such as frequent liver metastasis [28–30], together with our results supports this hypothesis. Thus, MSI-positive, solid-type, poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas may develop from glandular adenocarcinomas, exhibiting increasing histological diversity with tumor growth.

From the biological point of view, the present study demonstrated that there was no significant difference in prognosis between microsatellite-unstable and microsatellite-stable gastric carcinomas. This result was in accordance with reports by several investigators [4, 9]. However, other reports demonstrated that microsatellite-unstable carcinoma showed better prognosis, especially in stage II. In contrast, our results indicated worse prognosis in microsatellite-unstable carcinomas in stage II, which may be the result of histological differences among the cases examined. The reports in which microsatellite-unstable carcinoma had an association with intestinal-type histology preferably showed better prognosis [3, 5]. Thus, it is still controversial whether microsatellite-unstable carcinoma has better prognosis, even though the tumor has a lower incidence of lymph node metastasis.

In conclusion, MSI is preferentially observed in specific histological subtypes: papillary adenocarcinoma and solid-type, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. In addition, gastric carcinoma with MSI may originate from differentiated-type carcinoma, indicating histological diversity during tumor growth.

References

Han HJ, Yanagisawa A, Kato Y, Park JG, Nakamura Y. Genetic instability in pancreatic cancer and poorly differentiated type of gastric cancer. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5087–9.

Lee HS, Choi SI, Lee HK, Kim HS, Yang HK, Kang GH, et al. Distinct clinical features and outcomes of gastric cancers with microsatellite instability. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:632–40.

Beghelli S, de Manzoni G, Barbi S, Tomezzoli A, Roviello F, Di Gregorio C, et al. Microsatellite instability in gastric cancer is associated with better prognosis in only stage II cancers. Surgery (St. Louis). 2006;139:347–56.

Seo HM, Chang YS, Joo SH, Kim YW, Park YK, Hong SW, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics and outcomes of gastric cancers with the MSI-H phenotype. J Surg Oncol. 2009;99:143–7.

Corso G, Pedrazzani C, Marrelli D, Pascale V, Pinto E, Roviello F. Correlation of microsatellite instability at multiple loci with long-term survival in advanced gastric carcinoma. Arch Surg. 2009;144:722–7.

Gu M, Kim D, Bae Y, Choi J, Kim S, Song S. Analysis of microsatellite instability, protein expression and methylation status of hMLH1 and hMSH2 genes in gastric carcinomas. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:899–904.

Nakajima T, Akiyama Y, Shiraishi J, Arai T, Yanagisawa Y, Ara M, et al. Age-related hypermethylation of the hMLH1 promoter in gastric cancers. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:208–11.

Guo RJ, Arai H, Kitayama Y, Igarashi H, Hemmi H, Arai T, et al. Microsatellite instability of papillary subtype of human gastric adenocarcinoma and hMLH1 promoter hypermethylation in the surrounding mucosa. Pathol Int. 2001;51:240–7.

Strickler JG, Zheng J, Shu Q, Burgart LJ, Alberts SR, Shibata D. p53 mutations and microsatellite instability in sporadic gastric cancer: when guardians fail. Cancer Res. 1994;54:4750–5.

Wu MS, Lee CW, Shun CT, Wang HP, Lee WJ, Sheu JC, et al. Clinicopathological significance of altered loci of replication error and microsatellite instability-associated mutations in gastric cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1494–7.

Lin JT, Wu MS, Shun CT, Lee WJ, Wang JT, Wang TH, et al. Microsatellite instability in gastric carcinoma with special references to histopathology and cancer stages. Eur J Cancer. 1995;31A:1879–82.

dos Santos NR, Seruca R, Constancia M, Seixas M, Sobrinho-Simoes M. Microsatellite instability at multiple loci in gastric carcinoma: clinicopathologic implications and prognosis. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:38–44.

Kim H, Kim YH, Kim SE, Kim NG, Noh SH. Concerted promoter hypermethylation of hMLH1, p16 INK4A, and E-cadherin in gastric carcinomas with microsatellite instability. J Pathol. 2003;200:23–31.

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma, 2nd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:10–24.

Nakamura K, Sugano H, Takagi K. Carcinoma of the stomach in incipient phase: its histogenesis and histological appearances. Gann. 1968;59:251–8.

UICC International Unit Against Cancer. TNM classification of malignant tumours. 7th ed. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009.

Cravo M, Lage P, Albuquerque C, Chaves P, Claro I, Gomes T, et al. BAT-26 identifies sporadic colorectal cancers with mutator phenotype: a correlative study with clinico-pathological features and mutations in mismatch repair genes. J Pathol. 1999;188:252–7.

Zhou XP, Hoang JM, Cottu P, Thomas G, Hamelin R. Allelic profiles of mononucleotide repeat microsatellites in control individuals and in colorectal tumors with and without replication errors. Oncogene. 1997;15:1713–8.

Esemuede I, Forslund A, Khan SA, Qin LX, Gimbel MI, Nash GM, et al. Improved testing for microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer using a simplified 3-marker assay. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:3370–8.

Halling KC, Harper J, Moskaluk CA, Thibodeau SN, Petroni GR, Yustein AS, et al. Origin of microsatellite instability in gastric cancer. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:205–11.

Ferrasi AC, Pinheiro NA, Rabenhorst SH, Caballero OL, Rodrigues MA, de Carvalho F, et al. Helicobacter pylori and EBV in gastric carcinomas: methylation status and microsatellite instability. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:312–9.

Dietmaier W, Wallinger S, Bocker T, Kullmann F, Fishel R, Ruschoff J. Diagnostic microsatellite instability: definition and correlation with mismatch repair protein expression. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4749–56.

Jiao YF, Sugai T, Habano W, Suzuki M, Takagane A, Nakamura S. Analysis of microsatellite alterations in gastric carcinoma using the crypt isolation technique. J Pathol. 2004;204:200–7.

Lee HS, Lee BL, Kim SH, Woo DK, Kim HS, Kim WH. Microsatellite instability in synchronous gastric carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2001;91:619–24.

Song JP, Kitayama Y, Igarashi H, Guo RJ, Wang YJ, Kobayashi T, et al. Centromere numerical abnormality in the papillary, papillotubular type of early gastric cancer, a further characterization of a subset of gastric cancer. Int J Oncol. 2002;21:1205–11.

Arai T, Esaki Y, Sawabe M, Honma N, Nakamura K, Takubo K. Hypermethylation of the hMLH1 promoter with absent hMLH1 expression in medullary-type poorly differentiated colorectal adenocarcinoma in the elderly. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:172–9.

Fukayama M. Epstein–Barr virus and gastric carcinoma. Pathol Int. 2010;60:337–50.

Adachi Y, Mori M, Maehara Y, Sugimachi K. Poorly differentiated medullary carcinoma of the stomach. Cancer (Phila). 1992;70:1462–6.

Kaibara N, Kimura O, Nishidoi H, Makino M, Kawasumi H, Koga S. High incidence of liver metastasis in gastric cancer with medullary growth pattern. J Surg Oncol. 1985;28:195–8.

Yasuda K, Adachi Y, Shiraishi N, Maeo S, Kitano S. Papillary adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Gastric Cancer. 2000;3:33–8.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (TA No C22590329), and by a grant from the Smoking Research Foundation. We thank the staff at the Department of Pathology, Tokyo Metropolitan Geriatric Hospital, for their excellent technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Arai, T., Sakurai, U., Sawabe, M. et al. Frequent microsatellite instability in papillary and solid-type, poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas of the stomach. Gastric Cancer 16, 505–512 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-012-0226-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-012-0226-6