Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to compare the quality of life after the early postoperative period and before reaching 5 years postoperatively between patients who underwent laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy (Group A) and patients who underwent open distal subtotal gastrectomy (Group B).

Methods

The Korean versions of the European Organization for Research and Treatment (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (QLQ-C30) and a gastric cancer-specific module, the EORTC QLQ-STO22, were used to assess the quality of life of 80 patients who underwent laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy or open distal subtotal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. The postoperative period ranged between 6 months and 5 years.

Results

The global health status/quality of life scores of Groups A and B were 56.0 ± 19.0 and 57.4 ± 18.2, respectively (p = 0.729). Group A experienced worse quality of life in role functioning (p = 0.026), cognitive functioning (p = 0.034), fatigue (p = 0.039), eating restrictions (p = 0.009), and anxiety (p = 0.033). Group A showed a trend to experience worse quality of life in physical functioning, emotional functioning, social functioning, insomnia, and body image, albeit without statistical significance.

Conclusion

After the early postoperative period and before achieving long-term survival, patients who underwent laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy appeared to experience lower quality of life compared to patients who underwent open distal subtotal gastrectomy. This finding may be associated with the patients’ erroneously high expectations of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the first report on laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy (LADG) was published in 1994 [1], the number of patients with gastric cancer who undergo LADG has increased every year.

Many studies have shown the advantages of LADG over open distal subtotal gastrectomy (ODSG), such as cosmetic benefits, less pain, faster recovery, and shorter hospital stay [2–7]. The early postoperative quality of life (QoL) following LADG has been shown to be superior to that following ODSG [8, 9]. However, there have been some doubts about the long-term QoL benefits from LADG [10], and Yasuda et al. [11] showed that the long-term QoL of patients was similar for LADG and ODSG.

Because early postoperative QoL is better in patients who have undergone LADG than in those who have undergone ODSG, and because the long-term QoL is similar for both procedures, it would be logical to hypothesize that the mid-term QoL of patients who have undergone LADG may be similar to or slightly better than that in patients who have undergone ODSG. However, QoL is a subjective matter and the patient’s perception may differ from that of the clinician [12, 13].

The aim of this study was to compare the QoL of a LADG group and an ODSG group after the early postoperative period and before reaching 5 years postoperatively, when patients are generally considered to be disease-free. We investigated for differences between the patients’ subjective expectations and objective evaluation by clinicians during that period.

Patients and methods

The QoL data obtained from patients who visited our outpatient clinic for routine follow-up between March 2010 and November 2010 were retrospectively analyzed.

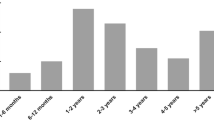

All patients had undergone curative surgery by LADG or ODSG with stapled Billroth I gastroduodenostomy and D2 extended lymphadenectomy for stage I gastric adenocarcinoma. Staging definition was in accordance with the seventh edition of the International Union Against Cancer (UICC) classification. In this study, we included only patients who had undergone the procedure at least 6 months previously and before they reached 5 years postoperatively.

Patients were excluded if they had past medical histories, comorbidities, or signs of recurrence that could have impacted on their QoL. Twenty-nine patients were excluded: 9 with cholecystectomies, 7 with gynecological conditions, 4 with colorectal cancer, 3 with cardiovascular conditions, 2 with cerebrovascular conditions, 2 with chronic liver diseases, 1 with renal transplantation, and 1 with chronic respiratory disease. Of 109 patients screened, 80 patients were included in this study.

The Korean versions of the European Organization for Research and Treatment (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (QLQ-C30) and a gastric cancer-specific module, the EORTC QLQ-STO22, were used to assess QoL, with permission from the EORTC. A research staff member explained the QoL questionnaires to each patient. Patients who agreed to participate in the study were asked to complete the questionnaire themselves. The answers were then translated into scores from 0 to 100, according to the scoring manual provided by the EORTC.

The EORTC QLQ-C30 is comprised of 15 scales; a global health status/QoL, five functional scales (physical, role, cognitive, emotional and social), three symptom scales (fatigue, nausea and vomiting, and pain), and six single items (dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhea, and financial difficulties). For the global health status/QoL and the five functional scales, a high score represents high QoL, but for the three symptom scales and six single items, a high score represents low QoL. The EORTC QLQ-STO22 is comprised of nine scales (dysphagia, pain, reflux, eating restrictions, anxiety, dry mouth, taste, body image and hair loss), and a high score represents low QoL.

With Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, the QoL of gastric cancer patients who were at least 6 months but less than 5 years after LADG was compared to that in patients during the same period after ODSG. The χ2 test and Student’s t test were used to compare items between groups, and a p value of less than 0.05 (p < 0.05) was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Science version 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

There were 43 men and 37 women (M:F = 1.16:1) with a mean age of 55.8 ± 10.4 years. The mean ages of patients in the LADG and ODSG groups were 54.0 ± 11.6 and 57.3 ± 9.3 years, respectively, and the difference was without statistical significance (Table 1). Time elapsed since surgery was not significantly different between the LADG and ODSG groups (22.2 ± 12.0 and 25.6 ± 12.9 months, respectively). However, the operation time was significantly longer in the LADG group, compared to the ODSG group (222.9 ± 45.9 and 169.4 ± 31.1 min, respectively; p < 0.001), and the number of retrieved lymph nodes was significantly less in the LADG group, compared to the ODSG group (53.8 ± 20.6 and 65.3 ± 21.4, respectively; p = 0.018).

In the LADG group, one patient experienced postoperative delayed gastric emptying. In the ODSG group, a number of postoperative complications were observed: 2 patients experienced delayed gastric emptying, 2 patients developed anastomotic leakage, 2 patients developed wound infection, and 1 patient experienced intraluminal bleeding. All complications were managed during the period of admission, and no patient suffered sequelae of complications at the time of completing the QoL questionnaires.

For the EORTC QLQ-C30, the global health status/QoL scores, at 56.0 ± 19.0 and 57.4 ± 18.2, respectively (p = 0.729) (Table 2), were not significantly different between the LADG and the ODSG groups. For the five functional scales, the LADG group had lower QoL for role functioning (p = 0.026) and cognitive functioning (p = 0.034). Although the differences did not reach statistical significance, the LADG group tended to have lower QoL for physical functioning (p = 0.054), emotional functioning (p = 0.065), and social functioning (p = 0.079). For the three symptom scales and the six single items, the LADG group had significantly lower QoL for fatigue (p = 0.039). The LADG group tended to have lower QoL for insomnia, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.083).

For the EORTC QLQ-STO22, the LADG group had lower QoL for eating restriction (p = 0.009) and anxiety (p = 0.033) (Table 3). Compared to the ODSG group, the LADG group tended to have lower QoL for body image, albeit without statistical significance (p = 0.064).

Discussion

Ever since the introduction of LADG, it has received considerable attention in the treatment of gastric cancer. Survival data of patients after LADG have been analyzed and were deemed comparable to the data after ODSG [14, 15]. There have been studies that investigated QoL after LADG. Adachi et al. [8] assessed the QoL in patients following LADG and ODSG, using their own questionnaire comprised of 24 questions, with a mean follow-up period of 24 months. That study demonstrated better QoL in patients after LADG regarding weight loss, swallowing difficulty, heartburn and belching, early dumping syndrome, and total score. These authors also asserted that LADG had been accepted as “a good operation” by the patients. Kim et al. [9] assessed the QoL of patients after LADG and ODSG, using the EORTC QLQ-C30 and STO22, at 7, 30, and 90 days postoperatively. Patients after LADG enjoyed better QoL in regard to global health status and for the following parameters: physical, role, emotional and social functioning, fatigue, pain, appetite loss, insomnia, dysphagia, reflux, eating restrictions, anxiety, dry mouth, and body image. Other than cosmetic benefits, an associated factor, other authors argued, was a lower incidence of adhesions [16, 17]. Yasuda et al. [11] assessed the QoL of long-term survivors after LADG and compared it to that after ODSG. The mean intervals after LADG and ODSG were 99.3 and 97.0 months, respectively. They used their own questionnaire comprised of 22 questions, and the QoL was similar for patients after LADG and ODSG. Although different tools were used to measure QoL in these studies, it appeared that LADG was superior to ODSG in terms of QoL in the early postoperative period, and that this benefit became dissipated long after surgery when patients are generally considered to be free of gastric cancer.

There have been studies comparing the QoL of gastric cancer patients after distal subtotal gastrectomy and total gastrectomy [18–20]. In the early postoperative period, patients who underwent distal subtotal gastrectomy experienced better QoL than patients who underwent total gastrectomy, but the QoL benefits of distal subtotal gastrectomy were lost as time elapsed. Eventually, the QoL of long-term survivors after distal subtotal gastrectomy and total gastrectomy was not significantly different.

Because patients’ QoL after distal subtotal gastrectomy and total gastrectomy has shown convergence as time passed, it would be logical to hypothesize that patient QoL after LADG and ODSG would also show convergence as time passes. We investigated the QoL of patients after LADG and that after ODSG during the period after the early postoperative period and before reaching long-term survival, and the outcomes were to the contrary. Patients after LADG experienced lower QoL than patients after ODSG in the functional scales, including role functioning and cognitive functioning. Even though the differences were not significant, patients after LADG tended to have lower QoL in the remaining functional scales: physical, emotional, and social functioning. Our study also indicated QoL deterioration for fatigue, eating restrictions, and anxiety in patients after LADG, and these patients also experienced lower QoL for insomnia and body image, albeit without statistical significance. It is interesting that fatigue, insomnia, eating restrictions, anxiety, and body image were in favor of LADG over ODSG during the early postoperative period [8], and somehow these favorable outcomes became unfavorable.

There are different ways to define QoL [13]. One definition of QoL is the gap between the patient’s expectations and the actuality [21]. This gap may well be described as patient satisfaction [22]. According to this definition of QoL, a person may have a high QoL if the gap between his or her expectations and actuality is small. In other words, the QoL of patients who underwent LADG would not be high, if their expectations were high. This could also be described as subjectivity, and the objective equivalence of two groups does not always mean subjective equivalence.

Unlike the extent of resection, which is basically determined by the location of the gastric cancer and not by patient preference, patients with early-stage gastric cancer may choose between LADG and ODSG. During the early postoperative period, patients who have undergone LADG may find their expectations met by actuality–small incisions and early recovery. However, as time passes, those who have undergone LADG may face the same problems as those who elected to undergo ODSG. If a patient with LADG has somewhat higher expectations at this point, this may result in a larger gap between expectations and actuality, leading to lower QoL than that in patients who elect to undergo ODSG. This indicates that there is some discordance between the patients’ subjective expectations and the clinicians’ objective evaluation of LADG and ODSG during this period.

As discussed earlier, LADG had been accepted as “a good operation” by patients with a mean follow-up period of 24 months, and they would recommend LADG to others [8]. Newly emerging techniques or tools such as laparoscopic surgery or robotic surgery are very attractive to surgeons, to media, and even to patients. While these newly emerging techniques are being adopted, the advantages are often emphasized while the older counterparts are somewhat de-emphasized, with or without the intention to do this. Recently, more people have been obtaining information about their conditions through the internet or other media even before they visit the surgical outpatient clinic. Often they come with a vague idea of LADG being superior to ODSG. It is the clinician’s duty to correct misconceptions by re-emphasizing to patients who have chosen LADG that the distal part of their stomach will be removed, and that they will face the same consequences of distal gastrectomy as those who have chosen ODSG. Educational programs such as preoperative or even postoperative lectures and booklets could be some ways to re-emphasise these points .

This “turn-around” phenomenon may differ by regions or countries depending on the accessibility of the general population to information on LADG and ODSG, and by personal relationships with patients who have undergone LADG or ODSG. Most of all, this phenomenon may be greatly influenced by the clinician, depending on how he or she communicates with patients about LADG or ODSG.

We do not have comparative QoL data for patients whose erroneous assumptions on LADG have been corrected by clinicians, and those whose assumptions have not been corrected. It would be unethical to conduct such a study because patients would be at risk of being given limited information about LADG and ODSG.

Patients with past medical histories of abdominal surgeries were excluded from the present study not only because of chances of having impaired QoL but also because a request for LADG may have been declined. We did not have absolute contraindications for LADG as long as the patient’s oncologic status was acceptable. However, there were some relative contraindications, which were past medical histories of abdominal surgeries and morbid obesity, which may require a special trocar. Regarding obesity, the body mass index values were not different between our LADG and ODSG groups, with the highest values being 29.8 and 30.9 kg/m2, respectively, and none of the patients who participated in this study were as obese as those who may have required a special trocar. It would be interesting to conduct a study on the QoL of patients with ODSG comparing the QoL of those who originally requested ODSG and that of those whose requests for LADG were declined.

The present study did not elucidate specific patient expectations. A further investigation, using a well-designed questionnaire in which patients are to make own comparisons between LADG and ODSG, would be interesting.

A limitation of this study is that there was a lack of longitudinal patient data from the early postoperative period to the time of attaining long-term survival. It would be interesting to investigate the pattern of QoL change through further follow-up. Designing a prospective trial, involving longitudinal acquisition of QoL data with details of altered requests for LADG and even for ODSG may be interesting.

Based on our analysis of 80 patients after the early postoperative period and before reaching 5 years postoperatively, we conclude that patients who have undergone LADG may experience unexpected reversal of QoL by experiencing lower QoL compared to those who have undergone ODSG until long-term survival is achieved. This finding may be associated with patients’ erroneously high expectations of LADG. It is our duty as clinicians to mitigate erroneous assumptions about LADG if we are to generate the most QoL benefits from LADG.

References

Kitano S, Iso Y, Moriyama M, Sugimachi K. Laparoscopy-assisted Billroth I gastrectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1994;4:146–8.

Adachi Y, Shiraishi N, Shiromizu A, Bandoh T, Aramaki M, Kitano S. Laparoscopy-assisted Billroth I gastrectomy compared with conventional open gastrectomy. Arch Surg. 2000;135:806–10.

Shimizu S, Uchiyama A, Mizumoto K, Morisaki T, Nakamura K, Shimura H, et al. Laparoscopically assisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: is it superior to open surgery? Surg Endosc. 2000;14:27–31.

Yano H, Monden T, Kinuta M, Nakano Y, Tono T, Matsui S, et al. The usefulness of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy in comparison with that of open distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2001;4:93–7.

Kitano S, Shiraishi N, Fujii K, Yasuda K, Inomata M, Adachi Y. A randomized controlled trial comparing open vs laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for the treatment of early gastric cancer: an interim report. Surgery. 2002;131:306–11.

Kitagawa Y, Kitano S, Kubota T, Kumai K, Otani Y, Saikawa Y, et al. Minimally invasive surgery for gastric cancer—toward a confluence of two major streams: a review. Gastric Cancer. 2005;8:103–10.

Ohtani H, Tamamori Y, Noguchi K, Azuma T, Fujimoto S, Oba H, et al. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials that compared laparoscopy-assisted and open distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:958–64.

Adachi Y, Suematsu T, Shiraishi N, Katsuta T, Morimoto A, Kitano S, et al. Quality of life after laparoscopy-assisted Billroth I gastrectomy. Ann Surg. 1999;229:49–54.

Kim YW, Baik YH, Yun YH, Nam BH, Kim DH, Choi IJ, et al. Improved quality of life outcomes after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: results of a prospective randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2008;248:721–7.

Liakakos T, Roukos DH. Is there any long-term benefit in quality of life after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer? Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1402–4.

Yasuda K, Shiraishi N, Etoh T, Shiromizu A, Inomata M, Kitano S. Long-term quality of life after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:2150–3.

van Knippenberg FC, de Haes JC. Measuring the quality of life of cancer patients: psychometric properties of instruments. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41:1043–53.

Bottomley A. The cancer patient and quality of life. Oncologist. 2002;7:120–5.

Huscher CG, Mingoli A, Sgarzini G, Sansonetti A, Di Paola M, Recher A, et al. Laparoscopic versus open subtotal gastrectomy for distal gastric cancer: five-year results of a randomized prospective trial. Ann Surg. 2005;241:232–7.

Mochiki E, Kamiyama Y, Aihara R, Nakabayashi T, Asao T, Kuwano H. Laparoscopic assisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: five years’ experience. Surgery. 2005;137:317–22.

Mochiki E, Nakabayashi T, Kamimura H, Haga N, Asao T, Kuwano H. Gastrointestinal recovery and outcome after laparoscopy-assisted versus conventional open distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. World J Surg. 2002;26:1145–9.

Gutt CN, Oniu T, Schemmer P, Mehrabi A, Büchler MW. Fewer adhesions induced by laparoscopic surgery? Surg Endosc. 2004;18:898–906.

Svedlund J, Sullivan M, Liedman B, Lundell L, Sjödin I. Quality of life after gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma: controlled study of reconstructive procedures. World J Surg. 1997;21:422–33.

Huang CC, Lien HH, Wang PC, Yang JC, Cheng CY, Huang CS. Quality of life in disease-free gastric adenocarcinoma survivors: impacts of clinical stages and reconstructive surgical procedures. Dig Surg. 2007;24:59–65.

Díaz De Liaño A, Oteiza Martínez F, Ciga MA, Aizcorbe M, Cobo F, Trujillo R. Impact of surgical procedure for gastric cancer on quality of life. Br J Surg. 2003;90:91–4.

Calman KC. Quality of life in cancer patients—an hypothesis. J Med Ethics. 1984;10:124–7.

Gotay CC, Korn EL, McCabe MS, Moore TD, Cheson BD. Quality-of-life assessment in cancer treatment protocols: research issues in protocol development. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1992;84:575–9.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank Kyung Eun Lee and Dong Soon Yu for their invaluable assistance with data management.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interests pertaining to the publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, S.S., Ryu, S.W., Kim, I.H. et al. Quality of life beyond the early postoperative period after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy: the level of patient expectation as the essence of quality of life. Gastric Cancer 15, 299–304 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-011-0113-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-011-0113-6