Abstract

Dientamoeba fragilis is a protozoan with a debated role in gastrointestinal (GI) disease. Although correlated to GI symptoms, no virulence factors have been described. In this study, we evaluated the cause of GI symptoms in children at two schools, with children aged 1 to 10 years, in the county of Jönköping, Sweden. D. fragilis infection correlated to GI symptoms in children and Enterobius vermicularis correlated to D. fragilis infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dientamoeba fragilis is a protozoan suspected of causing gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms [1, 2], although its aetiological role in GI disease is controversial [3–6]. The reported prevalence of D. fragilis in individuals suffering from GI symptoms varies from 1 to 70 % [4, 7, 8]. No difference in the prevalence of D. fragilis has been found in patients suffering from irritable bowel syndrome [6] or children with chronic abdominal pain [9] compared to individuals without symptoms. The life cycle of D. fragilis and its mode of transmission are not fully understood and a faecal–oral transmission seems unlikely [10]. It has been hypothesised that Enterobius vermicularis may serve as a vector for D. fragilis and, recently, D. fragilis DNA has been detected in E. vermicularis eggs [11].

Traditionally, parasites are detected by microscopy of concentrated unfixed or fixed faecal samples [12]. However, as trophozoites of D. fragilis rapidly degenerate outside the host, probably due to the lack of a cyst form [2, 13], a prompt fixation of faecal samples is essential. Also, concentration should be omitted and stained permanent smears or direct wet mounts should be used for the detection of D. fragilis trophozoites [12, 14].

Since the introduction of polymerase chain reaction (PCR), the detection of D. fragilis has increased [4, 7, 8]. In this study, we use a multiplex PCR assay modified for sodium acetic acid formaldehyde (SAF)-fixated samples to allow comparison with microscopy results on the same samples.

In March 2012, a school nurse alerted the Department for Control of Communicable Diseases in Jönköping County, Sweden, since many children at the school complained of GI symptoms.

We investigated possible infectious causes of GI symptoms in these children. In addition, a multiplex PCR for parasites on SAF-fixated faecal samples was established.

Materials and methods

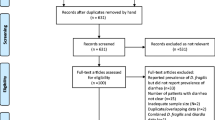

Study populations and GI symptoms

Faecal samples (n = 299) were obtained from school children (n = 146; 1 to 10 years old) and members of the staff (n = 16) at the school where children complained of GI symptoms (school A). Sticky tape tests for E. vermicularis detection were obtained from 47 children. Faecal samples from parents (n = 123) and siblings (n = 14) were also included. For comparison, faecal samples (n = 89) and sticky tape tests (n = 33) were obtained from children aged 1 to 10 years from another school (school B) in the county. In addition, the results from clinical samples (n = 7684) submitted for parasitological investigation to the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory, Jönköping, Sweden in 2012 were included.

Parents to children answered a questionnaire for the epidemiological investigation of GI diseases. Information on GI symptoms [abdominal pain (recurring and/or lasting more than 2 weeks), diarrhoea, nausea or constipation] within 3 months prior to testing was registered. Information regarding GI symptoms was not available for the clinical samples.

Microscopy for parasites

Faecal samples were immediately fixed in SAF. Samples were then homogenised and sifted, and half of the faecal suspension was concentrated by ethyl acetate treatment. Microscopy (100× and 400×) was done on concentrated material, on direct wet mounts from unconcentrated material and on sticky tape tests.

Multiplex real-time PCR for parasites

An SAF-fixated faecal solution (1000 μL) was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 1 min. Pellets were then washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) pH 7.4 for 1 min, followed by another centrifugation step. Pellets were suspended in a mixture of 280 μl AL lysis buffer and 20 μL proteinase K (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and incubated at 56 °C for 1 h with gentle agitation. Suspensions were then frozen at −196 °C for 30 min and, finally, heated at 98 °C for 15 min. DNA extraction was done with a MagAttract DNA Mini M48 kit (Qiagen) in an M48 instrument (Qiagen). Real-time PCR for parasite detection was done with the LightCycler 480 II instrument (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany), according to Verweij et al. [7, 15], modified by the inclusion of Entamoeba dispar [16].

Analysis of faecal samples

Samples from 30 children aged 6 to 8 years in school A were also analysed for the presence of GI pathogens, including standard faecal culture, PCR for norovirus, sapovirus [17] and enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) [18], and antigen detection for rotavirus and adenovirus (Coris BioConcept Combi-Strip, Gembloux, Belgium). All samples from schools A and B were analysed for parasites by multiplex PCR and microscopy, including direct wet mounts for trophozoite detection. Clinical samples were exclusively analysed by microscopy.

Results

GI bacterial and viral pathogens

In none of the 30 samples were Campylobacter spp., Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., Yersinia spp., EHEC, rotavirus, adenovirus or norovirus detected.

Parasites detected by microscopy

D. fragilis trophozoites were detected in direct wet mounts of unconcentrated faecal samples in 60, 60 and 15 % of samples from school A, school B and in clinical samples, respectively (Table 1). E. vermicularis eggs were detected in 13 out of 47 (28 %) sticky tape samples from school A and in 8 out of 33 (24 %) from school B. The prevalence of D. fragilis was 95 % (20 out of 21) in those positive for E. vermicularis and 69 % (41 out of 59) in those negative for E. vermicularis (p = 0.03). In concentrated faecal samples, Blastocystis hominis was found in nine children and 30 adults at school A and in four children from school B; no other pathogenic parasites or helminths were found. In the clinical samples, 30 E. histolytica/dispar, 90 Giardia intestinalis, 29 Cryptosporidium spp., 55 helminth eggs or larvae, and 787 B. hominis were found.

Prevalence of D. fragilis and recovery by PCR

The age-stratified prevalence of D. fragilis detected with microscopy is shown in Table 1. There was no difference in D. fragilis prevalence in samples from school A and school B. The prevalence in samples from the age group 6–10 years was higher at schools A and B and in clinical samples, compared to all the other age groups studied (p < 0.000 to p = 0.02). The prevalence of D. fragilis in individuals over 15 years old in school A (parents, staff and siblings) was higher compared to clinical samples (p < 0.0000).

All samples positive for D. fragilis by microscopy were also positive by PCR. Out of the total of 388 samples, D. fragilis was detected in 233 samples by microscopy and in 281 samples by PCR, respectively. This correlates to an increased recovery of 20 % (p < 0.000).

Relation between GI symptoms and D. fragilis infection

In school A, 102 questionnaires out of 155 were answered and in 76 children (75 %), one or more of the symptoms were documented. In school B, 60 out of 89 questionnaires were answered and in 32 children (53 %), one or more symptoms were documented. The prevalence of D. fragilis was higher in those having GI symptoms compared to children without symptoms (Table 2).

Discussion

In this study, we found that D. fragilis infection in children under the age of 11 years coincided with GI symptoms. This was not found in individuals over 10 years of age (data not shown). These findings are in agreement with previous studies on children [5] and adults [6], and suggest a role of D. fragilis in GI disease in children. The prevalence of D. fragilis was higher in the two schools studied compared to clinical samples. Interestingly, the prevalence in adults at school A was equally high as that in the children, whereas in clinical samples, the prevalence was less than 10 %. This is in agreement with previous findings of a high prevalence of D. fragilis in adults with close contact to children [4].

A drawback of this study was that GI symptoms were evaluated by reviewing questionnaires answered by parents and with no gradient scale to describe the severity of the symptoms. However, at school A, the symptoms were severe enough to alert the school nurse to contact the Department for Control of Communicable Diseases.

We found a higher prevalence of D. fragilis in children simultaneously infected with E. vermicularis compared to children with no E. vermicularis eggs detected. The results confirm previous studies based on the analysis of sticky tape test for the detection of E. vermicularis [19] but contradicts results from studies based on the analysis of faecal samples for E. vermicularis detection [20]. Our results indicate a role for E. vermicularis in the transmission of D. fragilis. Recently, D. fragilis DNA was detected in E. vermicularis eggs [11, 21] and in a study on metronidazole treatment of D. fragilis infection, E. vermicularis co-infection increased the risk of post-treatment D. fragilis infection [22]. Our finding of an equally high prevalence of D. fragilis in adults in contact with infected children raises the question regarding the routes of transmission to adults. Recently, a cyst form of D. fragilis has been detected in faeces from humans, but a possible faecal–oral transmission has not been documented [23, 24].

In this study, we found that a multiplex PCR, adapted to SAF-fixated faecal samples, increased the detection of D. fragilis by 20 % compared to microscopy.

In conclusion, our findings add to the opinion that D. fragilis might have an aetiological role in GI symptoms in children, and that E. vermicularis has a possible role in the transmission of D. fragilis.

References

Barratt JL, Harkness J, Marriott D, Ellis JT, Stark D (2011) A review of Dientamoeba fragilis carriage in humans: several reasons why this organism should be considered in the diagnosis of gastrointestinal illness. Gut Microbes 2(1):3–12

Johnson EH, Windsor JJ, Clark CG (2004) Emerging from obscurity: biological, clinical, and diagnostic aspects of Dientamoeba fragilis. Clin Microbiol Rev 17(3):553–570, table of contents

Lagacé-Wiens PR, VanCaeseele PG, Koschik C (2006) Dientamoeba fragilis: an emerging role in intestinal disease. CMAJ 175(5):468–469

Röser D, Simonsen J, Nielsen HV, Stensvold CR, Mølbak K (2013) Dientamoeba fragilis in Denmark: epidemiological experience derived from four years of routine real-time PCR. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 32(10):1303–1310

Banik GR, Barratt JL, Marriott D, Harkness J, Ellis JT, Stark D (2011) A case-controlled study of Dientamoeba fragilis infections in children. Parasitology 138(7):819–823

Krogsgaard LR, Engsbro AL, Stensvold CR, Nielsen HV, Bytzer P (2015) The prevalence of intestinal parasites is not greater among individuals with irritable bowel syndrome: a population-based case–control study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 13(3):507–513.e2

Verweij JJ, Mulder B, Poell B, van Middelkoop D, Brienen EA, van Lieshout L (2007) Real-time PCR for the detection of Dientamoeba fragilis in fecal samples. Mol Cell Probes 21(5–6):400–404

Maas L, Dorigo-Zetsma JW, de Groot CJ, Bouter S, Plötz FB, van Ewijk BE (2014) Detection of intestinal protozoa in paediatric patients with gastrointestinal symptoms by multiplex real-time PCR. Clin Microbiol Infect 20(6):545–550

de Jong MJ, Korterink JJ, Benninga MA, Hilbink M, Widdershoven J, Deckers-Kocken JM (2014) Dientamoeba fragilis and chronic abdominal pain in children: a case–control study. Arch Dis Child 99(12):1109–1113

Burrows RB, Swerdlow MA (1956) Enterobius vermicularis as a probable vector of Dientamoeba fragilis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 5(2):258–265

Ögren J, Dienus O, Löfgren S, Iveroth P, Matussek A (2013) Dientamoeba fragilis DNA detection in Enterobius vermicularis eggs. Pathog Dis 69(2):157–158

McHardy IH, Wu M, Shimizu-Cohen R, Couturier MR, Humphries RM (2014) Detection of intestinal protozoa in the clinical laboratory. J Clin Microbiol 52(3):712–720

Jepps MW, Dobell C (1918) Dientamoeba fragilis ng, n. sp., a new intestinal amoeba from man. Parasitology 10(03):352–367

Stark D, Barratt J, Roberts T, Marriott D, Harkness J, Ellis J (2010) Comparison of microscopy, two xenic culture techniques, conventional and real-time PCR for the detection of Dientamoeba fragilis in clinical stool samples. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 29(4):411–416

Verweij JJ, Blangé RA, Templeton K, Schinkel J, Brienen EA, van Rooyen MA, van Lieshout L, Polderman AM (2004) Simultaneous detection of Entamoeba histolytica, Giardia lamblia, and Cryptosporidium parvum in fecal samples by using multiplex real-time PCR. J Clin Microbiol 42(3):1220–1223

Visser LG, Verweij JJ, Van Esbroeck M, Edeling WM, Clerinx J, Polderman AM (2006) Diagnostic methods for differentiation of Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba dispar in carriers: performance and clinical implications in a non-endemic setting. Int J Med Microbiol 296(6):397–403

Nordgren J, Kindberg E, Lindgren PE, Matussek A, Svensson L (2010) Norovirus gastroenteritis outbreak with a secretor-independent susceptibility pattern, Sweden. Emerg Infect Dis 16(1):81–87

Bellin T, Pulz M, Matussek A, Hempen HG, Gunzer F (2001) Rapid detection of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli by real-time PCR with fluorescent hybridization probes. J Clin Microbiol 39(1):370–374

Girginkardeşler N, Kurt O, Kilimcioğlu AA, Ok UZ (2008) Transmission of Dientamoeba fragilis: evaluation of the role of Enterobius vermicularis. Parasitol Int 57(1):72–75

Vandenberg O, Peek R, Souayah H, Dediste A, Buset M, Scheen R, Retore P, Zissis G, van Gool T (2006) Clinical and microbiological features of dientamoebiasis in patients suspected of suffering from a parasitic gastrointestinal illness: a comparison of Dientamoeba fragilis and Giardia lamblia infections. Int J Infect Dis 10(3):255–261

Röser D, Nejsum P, Carlsgart AJ, Nielsen HV, Stensvold CR (2013) DNA of Dientamoeba fragilis detected within surface-sterilized eggs of Enterobius vermicularis. Exp Parasitol 133(1):57–61

Röser D, Simonsen J, Stensvold CR, Olsen KE, Bytzer P, Nielsen HV, Mølbak K (2014) Metronidazole therapy for treating dientamoebiasis in children is not associated with better clinical outcomes: a randomized, double-blinded and placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clin Infect Dis 58(12):1692–1699

Stark D, Garcia LS, Barratt JL, Phillips O, Roberts T, Marriott D, Harkness J, Ellis JT (2014) Description of Dientamoeba fragilis cyst and precystic forms from human samples. J Clin Microbiol 52(7):2680–2683

Munasinghe VS, Vella NG, Ellis JT, Windsor PA, Stark D (2013) Cyst formation and faecal-oral transmission of Dientamoeba fragilis—the missing link in the life cycle of an emerging pathogen. Int J Parasitol 43(11):879–883

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ögren, J., Dienus, O., Löfgren, S. et al. Dientamoeba fragilis prevalence coincides with gastrointestinal symptoms in children less than 11 years old in Sweden. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 34, 1995–1998 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-015-2442-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-015-2442-6