Abstract

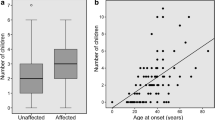

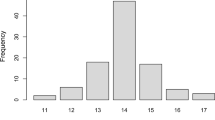

Spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1) is the major and likely the only type of autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia in the Sakha (Yakut) people of Eastern Siberia. The prevalence rate of SCA1 has doubled over the past 21 years peaking at 46 cases per 100,000 rural population. The age at death correlates closely with the number of CAG triplet repeats in the mutant ATXN1 gene (r = −0.81); most patients with low-medium (39–55) repeat numbers survived until the end of reproductive age. The number of CAG repeats expands in meiosis, particularly in paternal transmissions; the average total increase in intergenerational transmissions in our cohort was estimated at 1.6 CAG repeats. The fertility rates of heterozygous carriers of 39–55 CAG repeats in women were no different from those of the general Sakha population. Overall, the survival of mutation carriers through reproductive age, unaltered fertility rates, low childhood mortality in SCA1-affected families, and intergenerational transmission of increasing numbers of CAG repeats in the ATXN1 gene indicate that SCA1 in the Sakha population will be maintained at high prevalence levels. The low (0.19) Crow’s index of total selection intensity in our SCA1 cohort implies that this mutation is unlikely to be eliminated through natural selection alone.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Orr HT, Chung MY, Banfi S, Kwiatkowski TJ Jr, Servadio A, Beaudet AL, et al. (1993) Expansion of an unstable trinucleotide CAG repeat in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Nat Genet 4:221–226

Matilla T, Volpini V, Genis D, Rosell J, Corral J, Davalos A, et al. (1993) Presymptomatic analysis of spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1) via the expansion of the SCA1 CAG-repeat in a large pedigree displaying anticipation and parental male bias. Hum Mol Genet 2:2123–2128

Jodice C, Malaspina P, Persichetri F, Novelletto A, Spadaro M, Giunti P, et al. (1994) Effect of trinucleotide repeat length and parental sex on phenotypic variation in spinocerebellar ataxia 1. Am J Hum Genet 54:959–965

Ranum LP, Chung MY, Banfi S, Bryer A, Schut LJ, Ramesar R, et al. (1994) Molecular and clinical correlations in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1: evidence for familial effects on the age at onset. Am J Hum Genet 55:244–252

Schöls L, Bauer P, Schmidt T, Schulte T, Riess O (2004) Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxias: clinical features, genetics, and pathogenesis. Lancet Neurol 3:291–304

Goldfarb LG, Chumakov MP, Petrov PA, Fedorova NI, Gajdusek DC (1989) Olivopontocerebellar atrophy in a large Yakut kinship in Eastern Siberia. Neurology 39:1527–1530

Koneva LA, Konev AV, Kucher AN (2010) Simulation of the distribution of spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 in Yakut populations: model parameters and results of simulation. Genetika 46:990–999

Osakovskiy VL, Shatunov A, Platonov FA, Goldfarb LG (2004) The age of the mutant SCA1 chromosome in the Yakut population. Yakutsk Med J 2:63

Goldfarb LG, Vasconcelos O, Platonov FA, Lunkes A, Kipnis V, Kononova S, et al. (1996) Unstable triplet repeat and phenotypic variability of spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Ann Neurol 39:500–506

Prestes PR, Saraiva-Pereira ML, Silveira I, Sequeiros J, Jardim LB (2008) Machado-Joseph disease enhances genetic fitness: a comparison between affected and unaffected women and between MJD and the general population. Ann Hum Genet 72:57–64

Pakendorf B, Novgorodov IN, Osakovskij VL, Danilova AP, Protod’jakonov AP, Stoneking M (2006) Investigating the effects of prehistoric migrations in Siberia: genetic variation and the origins of Yakuts. Hum Genet 120:334–353

Zoghbi HY, Pollack MS, Lyons LA, Ferrell RE, Daiger SP, Beaudet AL (1988) Spinocerebellar ataxia: variable age of onset and linkage to human leukocyte antigen in a large kindred. Ann Neurol 23:580–584

Crow JF (1958) Some possibilities for measuring selection intensities in man. Hum Biol 30:1–13

Kononova SK, Sidorova OG, Fedorova SA, Platonov FA, Izhevskaya VL, Khusnutdinova EK (2014) Bioethical issues of preventing hereditary diseases with late onset in the Sakha Republic (Yakutia). Int J Circumpolar Health 73:25062

Subramony SH, Ashizawa T. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. In: Pagon RA, et al., Editors. GeneReviews®, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, 2015 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1116/)

Platonov FA (2003) The hereditary cerebellar ataxia type 1 in Yakutia. Dissertation, Мoscow, p. 178

Paradisi I, Ikonomu V, Arias S (2015) Spinocerebellar ataxias in Venezuela: genetic epidemiology and their most likely ethnic descent. J Hum Genet. doi:10.1038/jhg.2015.131

Rengaraj R, Dhanaraj M, Arulmozhi T, Chattopadhyay B, Battacharyya NP (2005) High prevalence of spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 in an ethnic Tamil community in India. Neurol India 53:308–311

Sumathipala DS, Abeysekera GS, Jayasekara RW, Tallaksen CM, Dissanayake VH (2013) Autosomal dominant hereditary ataxia in Sri Lanka. BMC Neurol May 1:13–39

Onodera Y, Aoki M, Tsuda T, Kato H, Nagata T, Kameya T, Abe K, Itoyama Y (2000) High prevalence of spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1) in an isolated region of Japan. J Neurol Sci 178:153–158

Velázquez Pérez L, Cruz GS, Santos Falcón N, Enrique Almaguer Mederos L, Escalona Batallan K, et al. (2009) Molecular epidemiology of spinocerebellar ataxias in Cuba: insights into SCA2 founder effect in Holguin. Neurosci Lett 454:157–160

Frontali M, Sabbadini G, Novelletto A, Jodice C, Naso F, Spadaro M, et al. (1996) Genetic fitness in Huntington’s disease and spinocerebellar ataxia 1: a population genetics model for CAG repeat expansions. Ann Hum Genet 60:423–435

Carey N, Johnson K, Nokelainen P, Peltonen L, Savontaus ML, Juvonen V, et al. (1994) Meiotic drive at the myotonic dystrophy locus? Nat Genet 6:117–118

Index of total selection (Crow’s index) (1991) In: Stevenson JC (ed) Dictionary of concepts in physical anthropology. New York, pp. 233–236

Khongsdier R (2000) Population genetics in Northeast India: an overview. In: Khongsdier R (ed) Contemporary research in anthropology. Commonwealth Publishers, New Delhi

Demetrius L, Gundlach VM, Ziehe M (2007) Darwinian fitness and the intensity of natural selection: studies in sensitivity analysis. J Theor Biol 249:641–653

Kucher AN, Danilova AL, Koneva LA, Nogovitsyna AN (2006) The population structure of rural settlements of Sakha Republic (Yakutia): ethnic, sex, and age composition and vital statistics. Genetika 42:1718–1726

Tarskaia LA, El’chinova GI, Varzar AM, Shabrova EV (2002) Genetic and demographic structure of the Yakut population: reproduction indices. Genetika 38:985–991

Acknowledgments

The study was funded in part by the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation through individual or group projects: PFA—project 1742, TDG, NTS, YNV, and NVP—project 18.1742.2014/K and KSK—project 6.656.2014/K. KT was supported by the Department of Pathology and Molecular Medicine, Queen’s University. GLG was funded in part by the Intramural Research Programs of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. NR was funded through a SEAMO New Clinician-Scientist Investigator Award and the Queen’s University Principal’s Development Fund. The authors wish to thank Dr. A.L. Suhomâsova for helpful advice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and animal rights and informed consent

We complied with the ethical principles regarding research involving human subjects set forth in the Belmont Report and the Declaration of Helsinki, and informed consent has been obtained from each study participant.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Platonov, F.A., Tyryshkin, K., Tikhonov, D.G. et al. Genetic fitness and selection intensity in a population affected with high-incidence spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Neurogenetics 17, 179–185 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10048-016-0481-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10048-016-0481-5