Abstract

Purpose

Gender stereotypes refer to consensual or cultural shared beliefs about the attributes of men and women, influencing society behaviors, interpersonal relationships, education, and workplace. The literature has shown the existence of gender stereotypes on career choices, internalization of roles, and school and social experiences and demonstrates the impact of demographic factors on stereotypes. However, all the studies conducted in Italy available in scientific literature analyzed small sample sizes within specific schools of university settings, with a limited age range.

Methods

To assess the current state of gender stereotypes in Italy, we conducted an online survey from October 2022 to January 2023 on the general population residing in Italy. The questionnaire comprised sociodemographic factors and questions about gender stereotypes, investigating six fields: games, jobs, personality traits, home and family activities, sports, and moral judgments.

Results

The study involved 1854 participants, mostly women (70.1%) with an undergraduate or postgraduate degree (57.5%). The statistical and descriptive analyses revealed that gender stereotypes influenced respondents’ beliefs, with statistically significant effects observed in most questions when stratifying by age, gender, and degree. Principal component analysis was performed to assess latent variables in different fields, revealing significant main stereotypes in each category. No statistically significant differences between men and women were found for the fields home and family activities, games, and moral judgments, confirming that stereotypes affect both men and women in the same way.

Conclusions

Our results show the persistence of gender stereotypes in any fields investigated, although our cohort is predominantly composed of high educational level women living in the North of Italy. This demonstrates that the long-standing gender stereotypes are prevalent, pernicious, and, unfortunately, internalized at times even by successful women pushbacking and sabotaging them unconsciously.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gender stereotypes refer to consensual or cultural shared beliefs about the attributes of men and women, from sex-based categorization and biological differences to social and cultural group representations (Eagly et al. 2020; Ellemers 2018). Constructs like communality and agency are used in gender stereotype studies, with communality related to affectionate traits, orienting people toward others, being more prevalent in females, and agency related to goal-achievement, including assertiveness and competitiveness, prevailing in males (Sczesny et al. 2018).

These stereotypes influence societal behaviors, impacting relationships, education, and the workplace, with physical and psychological effects. Stereotypes associate high-level intellectual abilities with men, discouraging women from pursuing certain careers, and these stereotypes are endorsed by young children, shaping their interests (Bian et al. 2017). This can be observed in the disparity between men and women in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM), in which women are largely underrepresented (Botella et al. 2019; Reinking & Martin 2018). Women are also underrepresented in occupations requiring competitiveness and physical resistance and overrepresented in jobs requiring empathy and communality. There is still a disparity in housework and childcare, often due to internalized beliefs (Cortes & Pan 2018; Hentschel et al. 2019).

Few studies have been performed about gender stereotypes using representative samples. A meta-analysis conducted in the USA integrating 16 public opinion polls on gender stereotypes, extending over 70 years and including about 30,000 adults, showed that affectionate and emotional characteristics were more related to women, with this relation increasing over time. Features such as ambition and courage were more associated with men, without changes over time. Although women gained in competence perception relative to men, gender equality inferences on this domain, including intelligence and creativity, increased with time (Eagly et al. 2020). Another study compared gender stereotype data collected in the USA in 1980 to data collected in 2014 to analyze if stereotypes have changed with more women participating in workforce, athletics, and education. Results showed that stereotypes remained stable, except for an increase in stereotyping of female roles (Haines et al. 2016).

Few gender stereotype studies were performed in Italy. Ramaci and collaborators explored the influence of gender stereotypes on adolescents’ career choices through self-report questionnaires assessed in 120 Italian high school students, highlighting the impact of age, gender, and parents’ profession on vocational decision-making (Ramaci et al. 2017). Professional and social identity diverged as individuals grew older and males presented higher perceived occupational self-efficacy in military, scientific-technological, and agrarian occupations compared to females (Ramaci et al. 2017). Siyanova-Chanturia and colleagues investigated real-time processing of gender stereotypes, investigating 28 university students, 30 older adults, and 85 children aged 8–11 in the province of Modena, Italy. The participants were required to make quick judgments on whether two auditorily presented words, one representing a masculine or feminine stereotype and the other a male or female kinship term, could both be used to describe the same individual. Participants responded faster when the target gender was congruent with the stereotypical gender use of the preceding prime, pointing to gender asymmetric perceptions and mental representations of words (Siyanova-Chanturia et al. 2015). Cerbara and collaborators conducted a survey through a structured questionnaire in schools of Rome, Italy, on 412 children aged 8–11 and examined the adherence to gender roles among children, emphasizing the internalization of traditional gender roles and its association with age and prosociality (Cerbara et al. 2022). Results showed the internalization of traditional gender roles, with boys accepting more male roles and girls accepting more female roles, with acceptance decreasing as age increases, suggesting that gender stereotypes are internalized at a young age, being influenced by primary socialization (Cerbara et al. 2022). Finally, Musso and collaborators studied 213 Italian adolescents in Apulia and 214 Nigerian adolescents in Enugu State, in secondary school, measuring school empowerment and engagement, STEM-gender stereotypes, and socioeconomic status (Musso et al. 2022). Nigerian girls and boys had higher levels of school empowerment and engagement, and STEM-gender stereotypes compared to Italian peers, and boys scored higher on school empowerment and STEM-gender stereotypes. Higher school empowerment was related to lower STEM-gender stereotypes in both Italian and Nigerian girls’ groups, while higher school engagement was associated with lower STEM-gender stereotypes only in Nigerian groups.

In summary, the national studies investigated different aspects of gender stereotypes and their effects on specific populations. Despite the differences in methodologies and designs, all studies highlighted the impact of gender stereotypes on diverse aspects of individuals’ lives, including career choices, language processing, and adherence to traditional gender roles. The studies focused on small groups in particular settings, involving individuals with a narrow age range, and examined restricted aspects of gender stereotypes, emphasizing the need for broader investigations. To address this gap, we conducted an online survey among individuals residing in Italy, with the objective of depicting the current state of gender stereotypes.

Materials and methods

Study design

We conducted an online survey to perform an exploratory research analysis using a Google Form from the beginning of October 2022 to the end of January 2023. Eligible participants were aged 15 or older, residing in Italy. To ensure a diverse audience, the survey link was widely spread, distributed among university colleagues, health professionals, and students in different regions. Social networks maximized the reach of the survey. We used a snowball sampling procedure by asking participants to disseminate the survey link among contacts. No Ethics formal approval was needed for this survey. To participate, individuals had to answer a yes–no question confirming their voluntary willingness to participate in the survey. Once confirmed, participants were directed to anonymously complete a self-report questionnaire.

Measures

The questionnaire consisted of two sections: sociodemographic factors and gender stereotypes. The online survey took about 10 min to complete and was written in Italian. The sociodemographic variables included gender, age, education, field of study, occupation, marital status, region of residence, and geographical origin of one’s family. Since there are no validated scales available on this topic, we created an ad hoc questionnaire to assess gender stereotypes, comprising 56 questions developed based on a literature review. The items investigated six fields (games, profession/jobs, personality traits, home and family activities, sports, and moral judgments) randomly displayed in the questionnaire. Three items were reversed questions inserted to control the reliability of each subject’s answers. Gender stereotypes were assessed using a Likert scale, including 1 (“completely agree”), 2 (“strongly agree”), 3 (“somewhat agree”), 4 (“slightly disagree”), 5 (“strongly disagree”), and 6 (“no difference between men and women”).

Statistical analysis

The chi-square test was applied to analyze the variables. Since the questionnaire contained six latent constructs, for each of them, we applied principal component analysis (PCA) (Jolliffe & Cadima 2016) to extract a small number of latent variables, easily interpret, and able to summarize these concepts not directly measurable. To identify the optimal number of components for each subgroup of items, the proportion of variance explained was observed, considering the Principal Components (PCs) that, in cumulative terms, explained at least 70% of the total variance. Loadings were extracted from the analysis output to show the contribution of each item on the component itself. Loadings could be positive or negative, indicating the direction and strength of the relationship between items and the corresponding PC. Larger absolute values suggested a stronger influence of one (or more) item on the PC and a significant contribution to its definition. Conversely, items with low or near-zero coefficients on the loadings had little impact on the component.

Results

A total of 1880 participants completed the questionnaire. Two expert psychologist reviewers independently checked for incongruent answers in the control questions, excluding subjects who answered unreliably and 26 respondents were excluded. The final sample consisted of 1854 subjects, with 70.1% being women and 57.5% possessing at least a university degree. Detailed socio-demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Descriptive results presenting the overall percentage of agreement among respondents are shown in Table 2. The total percentage of agreement was computed by summing the percentages of responses “completely agree,” “strongly agree,” and “somewhat agree.” Sentences with the highest agreement percentages in the total cohort, accounting for more than 25% each, were as follows: “Rugby is a sport for males,” “Women are more sensitive than men,” “Women are braver than men,” “Boxing is a sport for males,” “Working as a babysitter is for women,” and “The military profession is for men.”

We conducted stratified analyses by age, gender, and degree since all categories for these variables were numerically well-represented. For most items, we found highly significant effects, confirming that these variables strongly influence gender stereotypes. We observed significant effects in 54 questions when stratifying by age, 49 questions when stratifying by gender, and 51 when stratifying by degree, out of 56 questions. Detailed results are available in Supplementary Table 1Sa to 6Sc.

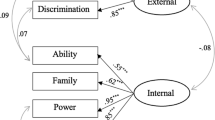

PCA was conducted to evaluate latent variables from the corresponding fields (Supplementary Table 7S). This was possible due to a preliminary analysis demonstrating a strong positive correlation among all individual items (correlation p-values < 0.05) (data available upon request).

For “home and family activities,” four latent variables lead to an explained variance ≥ 70%. The first component accounted for 47% of the variance and was primarily influenced by three items: “Ironing is an activity for women,” “Men drive better than women,” and “It is women, more than men, who must take care of the children.” When examining the field games,” three latent variables achieved an explained variance greater than 70%. The first component explained 52% of the variance and was mainly influenced by the item “Playing with dolls is for girls.” For “moral judgments,” two latent variables were considered. The first component, responsible for 66% of the explained variance, was primarily influenced by two items: “It is understandable that a man, more than a woman, can lose patience” and “In a couple, female infidelity is more serious than male infidelity.” For these three fields, no significant differences were found when conducting separate analyses for women and men.

For “personality traits,” six latent variables lead to an explained variance ≥ 70%. The first component, explaining 40% of the variance, was influenced by three items: “Women are more sensitive than men,” “Women are more determined than men,” and “Women are more cunning than men.” However, among women, two items had a greater influence (“Women are braver than men” and “Women are more determined than men”), while among men, two different items were more influential (“Women are more cunning than men” and “Women are more sensitive than men”).

For “profession/jobs,” four latent variables were considered and the first component, accounting for 48% of the explained variance, was influenced by two items: “The military profession is for men” and “Working as a babysitter is for women.” Among men, an additional item (“Working in a butcher shop is for men”) also had an impact on the first component, explaining 52% of the variance.

Finally, when examining “sports,” three latent variables explained a variance ≥ 70%. The first component, explaining 59% of the variance, was influenced by two items: “Boxing is a sport for males” and “Rugby is a sport for males.” Among males, in addition to the aforementioned items, two other components contributed to the variance (57%): “Artistic gymnastics is for females” and “Football is a sport for males.”

The main results coming from the different analyses performed indicating the most relevant items in terms of stereotypes are summarized in Fig. 1.

Discussion

We conducted an online survey to perform an exploratory research analysis in 1854 participants residing in Italy to depict the state of gender stereotypes. Gender stereotypes strongly influenced respondents’ beliefs, with statistically significant effects observed in most questions when stratifying by age, gender, and education, showing the influence of demographic factors. Indeed, highly significant effects were observed for the majority of items, specifically for 96% of the questions when stratifying by age, 91% of the questions when stratifying by degree, and 87% of the questions when stratifying by gender. These results provide compelling evidence regarding the influence of gender stereotypes on individual’s beliefs across different demographic groups and their ability to shape perceptions and beliefs in the studied population. PCA was performed to assess latent variables in different fields, revealing substantial main stereotypes in each category. For “home and family activities,” “games,” and “moral judgments,” the results did not reveal a statistically significant difference between men and women, demonstrating that stereotypes had an equal impact on both genders.

Studies from the literature have examined the presence of gender stereotypes and their impacts on career aspirations, vocational decision-making, internalization of gender roles, and the representation of gender subgroups in different cultures. Unfortunately, as previously described, few studies have been performed in Italy (Cerbara et al. 2022; Musso et al. 2022; Ramaci et al. 2017; Siyanova-Chanturia et al. 2015). When comparing the findings of these studies with ours, some common themes can be identified, despite the different methodologies. The studies acknowledge the existence of gender stereotypes on career choices, internalization of roles, and school and social experiences and demonstrate the impact of demographic factors on gender stereotypes. However, the studies conducted in Italy available in scientific literature analyzed small sample sizes with a limited age range, within particular settings, such as schools or university environments. Our study adds a valuable contribution to the literature in the theme, by analyzing a broader sample, with a larger age range distributed in different national settings. Besides, we have analyzed various aspects of gender stereotypes by including questions investigating diverse fields, including games, profession/jobs, personality traits, home and family activities, sports, and moral judgments.

Some limitations must be addressed. In our cohort, there is a higher prevalence of women. It is known that gender stereotypes affect women more directly as they are often targeted by these stereotypes, probably enhancing their motivation to engage in discussions on these matters. When investigating the existence of stereotypes that tend to disadvantage one category over another, it is mainly representatives of the disadvantaged category who respond. Women are increasingly empowered to challenge stereotypes and address gender-related issues, making them more interested in speaking about and offering help with these topics. These factors may contribute to women being more inclined to respond to gender stereotypes surveys (Ellemers 2018; Hentschel et al. 2019).

Approximately 57% of the respondents achieved at least a 3-year university degree. Low occupational class and educational level have been associated with a low participation rate, despite the fact that determinants of non-participation have varied among research and communities (Reinikainen et al. 2018). Additionally, issues related to stereotypes and social prejudices are perceived differently by people with low or high educational attainment. People with low education are less sensitive to these issues and tend to act as if stereotypes describe reality as it must be, without reasoning about it (O’Brien et al. 2020; Shu et al. 2022). Conversely, people with higher education tend to be more sensitive to these issues (Reinikainen et al. 2018). If we also consider that, in Italy, women tend to have a higher level of schooling than men and that women tend to prefer university paths related to social sciences, this might explain why mostly women with high schooling participated in this survey.

Despite using the same distribution strategies, about 85% of respondents live in the North of Italy, indicating possible difficulties in addressing this issue in some areas. Italy is conventionally divided into North, Center, and South. In addition to geopolitical and economic characteristics, this division reflects cultural differences, also based on a lesser or greater acceptance of gender stereotypes. Northern people tend to be less influenced by stereotypes, claiming greater freedom in this regard. People from the South tend to be more influenced by these stereotypes and not question them, which is why the further one moves toward Southern Italy, the less people tend to respond to a survey that has the flavor of subverting a recognized order. According to a report of the National Institute of Statistics in Italy in 2019, gender stereotypes are present in 58.8% of the Italian population, being more prevalent among older and less educated individuals and more frequent in the South.

Moreover, like several surveys, a neutral response bias in which the participant chooses the neutral answer every time (“somewhat agree” or “slightly disagree,” in our study), indicating low interest in the survey and looking to answer questions as quickly as possible, can have affected our survey. In the so-called sensitive surveys, the neutral answers simultaneously indicate a desire to contribute to the survey but also the fear of going too far and leaving a sort of norm that respondents have in mind about how things go in the general population. To reduce this bias, we gave the possibility to answer “no” (“no difference between men and women”), putting the responders in the state to make a clear choice. The percentage results indicated that no neutral response bias influenced our survey.

We cannot exclude the socially desirable responding bias, the tendency of respondents to give predominantly positive self-descriptions. Indeed, due to the topic afforded in our survey, it is higher the probability to answer in a socially desirable way. Another limitation is that we did not examine or control the collected data for potential influences on mental health and psychological well-being, such as symptoms of anxiety, stress, and depression. This aspect is relevant and should be addressed in future research.

Despite these limitations and potential pitfalls, our survey has several strengths. It is the only national survey conducted on a large-scale population with a great sample size, providing a valuable view of the prevalence of gender stereotypes for Italy, although with limited national geographical representation. By including diverse age ranges, our survey may capture the varying perspectives of individuals from different generations. As mentioned, previous research on gender stereotypes in Italy has been conducted on small samples, in specific cities and settings, focusing on particular stereotypical dimensions. By examining a broader population, our approach increases the generalizability of the findings to a wider Italian population.

Our results show the persistence of gender stereotypes in any fields investigated, although our cohort is predominantly composed of high educational level women living in the North of Italy. This demonstrates that the long-standing gender stereotypes are prevalent, pernicious, and, unfortunately, internalized at times even by successful women pushbacking and sabotaging them unconsciously. Gender stereotypes can restrict a woman’s or man’s ability to grow personally, pursue a career, and/or make decisions about their lives, becoming damaging. Harmful stereotypes support injustices, whether they are blatantly hostile (such as “Ironing is an activity for women”) or apparently innocuous (such as “Women are more cunning” or “Women are more sensitive than men”). Women are frequently targeted by prejudice due to gender stereotypes. Many rights, including the right to health, an adequate standard of living, education, marriage and family relationships, jobs’ career, salary equality, freedom of expression, political participation and representation, and freedom from gender-based violence, are all violated as a result. The expectations of how men and women should act are shaped by the long-standing gender roles that have been instilled throughout the world. These societal standards and expectations significantly impact mental health (Arcand et al. 2020; Rice et al. 2021), increasing the risk to develop anxiety and depressive disorders, which affect more women than men (Carvalho Silva et al. 2023; Hantsoo & Epperson 2017). Indeed, mental health disorders such as anxiety and major depressive disorder are more commonly diagnosed in women than in men, with these psychopathologies affecting females at almost twice the rate of males (Salk et al. 2017). The female lifespan is characterized by several distinct stages, each with a unique hormonal environment and psychosocial context that significantly influences the susceptibility to psychiatric disorders (Hantsoo & Epperson 2017). Prevalence, clinical presentation, and treatment approaches differ significantly between men and women due to sex-related differences that are influenced by developmental stage, reproductive events, and hormonal status (Hantsoo & Epperson 2017). Although the role of biological factors has been explored, including physiological reactivity and hormonal factors, gender roles and stereotypes should also be considered (Arcand et al. 2020). For individuals who do not conform to traditional gender roles, the experience of depression and anxiety can be compounded by identity conflict and social stigma. It can be difficult for non-conforming people to balance their self-identity with society standards (Mousavi et al. 2019). They may feel misunderstood or rejected by their groups, which can lead to a strong sense of loneliness as a result of this conflict. Depression and anxiety problems can be made worse by social stigmatization of people who question conventional gender roles. Chronic stress and mental suffering might result from the dread of criticism, prejudice, or violence. Recognizing and challenging these stereotypes are essential for promoting gender equality and improving women’s mental well-being.

Despite the fact that our cohort is primarily made up of highly educated women who live in the northern part of Italy, we were able to achieve substantial results regarding gender stereotypes. On one hand, our research clearly indicates that gender stereotypes are still strong, affecting any part of society. On the other hand, we probably catch only the tip of the iceberg. Indeed, certain groups of women, such as those from minority groups, those with disabilities, those from lower caste groups or with lower economic status, migrants, etc., may be disproportionately negatively affected by gender stereotypes when they are combined and intersected with other stereotypes, increasing the risk of loneliness and isolation and reducing their self-identity expression. Consequently, in order to reduce the risk of various women’s mental disorders and promote mental well-being, it is crucial to develop a society that values variety and offers people a safe environment to explore and express their true selves.

Data availability

Data are available upon request.

References

Arcand M, Juster R-P, Lupien SJ, Marin M-F (2020) Gender roles in relation to symptoms of anxiety and depression among students and workers. Anxiety Stress Coping 33(6):661–674. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2020.1774560

Bian L, Leslie S-J, Cimpian A (2017) Gender stereotypes about intellectual ability emerge early and influence children’s interests. Science (New York NY) 355(6323):389–391. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aah6524

Botella C, Rueda S, López-Iñesta E, Marzal P (2019) Gender diversity in STEM disciplines: a multiple factor problem. Entropy 21(1):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/e21010030

Carvalho Silva R, Pisanu C, Maffioletti E, Menesello V, Bortolomasi M, PROMPT consortium, Gennarelli M, Baune BT, Squassina A, Minelli A (2023) Biological markers of sex-based differences in major depressive disorder and in antidepressant response. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol J Eur Coll Neuropsychopharmacol 76:89–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2023.07.012

Cerbara L, Ciancimino G, Tintori A (2022) Are we still a sexist society? Primary socialisation and adherence to gender roles in childhood. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063408

Cortes P, Pan J (2018) Occupation and Gender. In S. L. Averett, L. M. Argys, & S. D. Hoffman (Eds.), The oxford handbook of women and the economy (pp. 424–452). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190628963.013.12

Eagly AH, Nater C, Miller DI, Kaufmann M, Sczesny S (2020) Gender stereotypes have changed: a cross-temporal meta-analysis of U.S. public opinion polls from 1946 to 2018. Am Psychol 75(3):301–315. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000494

Ellemers N (2018) Gender stereotypes. Annu Rev Psychol 69:275–298. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011719

Haines EL, Deaux K, Lofaro N (2016) The times they are a-changing … or are they not? A comparison of gender stereotypes, 1983–2014. Psychol Women Q 40(3):353–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684316634081

Hantsoo L, Epperson CN (2017) Anxiety disorders among women: a female lifespan approach. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ) 15(2):162–172. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.focus.20160042

Hentschel T, Heilman ME, Peus CV (2019) The multiple dimensions of gender stereotypes: a current look at men’s and women’s characterizations of others and themselves. Front Psychol 10:11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00011

Jolliffe IT, Cadima J (2016) Principal component analysis: a review and recent developments. Philos Trans R Soc Math Phys Eng Sci 374(2065):20150202. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2015.0202

Mousavi MS, Shahriari M, Salehi M, Kohan S (2019) Gender identity development in the shadow of socialization: a grounded theory approach. Arch Women’s Mental Health 22(2):245–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-018-0888-0

Musso P, Ligorio MB, Ibe E, Annese S, Semeraro C, Cassibba R (2022) STEM-gender stereotypes: associations with school empowerment and school engagement among Italian and Nigerian adolescents. Front Psychol 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.879178

O’Brien LT, Garcia DM, Blodorn A, Adams G, Hammer E, Gravelin C (2020) An educational intervention to improve women’s academic STEM outcomes: divergent effects on well-represented vs. underrepresented minority women. Cult Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 26(2):163–168. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000289

Ramaci T, Pellerone M, Ledda C, Presti G, Squatrito V, Rapisarda V (2017) Gender stereotypes in occupational choice: a cross-sectional study on a group of Italian adolescents. Psychol Res Behav Manag 10:109–117. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S134132

Reinikainen J, Tolonen H, Borodulin K, Härkänen T, Jousilahti P, Karvanen J, Koskinen S, Kuulasmaa K, Männistö S, Rissanen H, Vartiainen E (2018) Participation rates by educational levels have diverged during 25 years in Finnish health examination surveys. Eur J Pub Health 28(2):237–243. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckx151

Reinking A, Martin B (2018) The gender gap in STEM fields: theories, movements, and ideas to engage girls in STEM. J New Approaches Educ Res 7(2):148–153. https://doi.org/10.7821/naer.2018.7.271

Rice S, Oliffe J, Seidler Z, Borschmann R, Pirkis J, Reavley N, Patton G (2021) Gender norms and the mental health of boys and young men. Lancet Public Health 6(8):e541–e542. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00138-9

Salk RH, Hyde JS, Abramson LY (2017) Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms. Psychol Bull 143(8):783–822. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000102

Sczesny S, Nater C, Eagly AH (2018) Agency and communion. In Agency and Communion in Social Psychology (pp. 103–116). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203703663-9

Shu Y, Hu Q, Xu F, Bian L (2022) Gender stereotypes are racialized: a cross-cultural investigation of gender stereotypes about intellectual talents. Dev Psychol 58(7):1345–1359. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001356

Siyanova-Chanturia A, Warren P, Pesciarelli F, Cacciari C (2015) Gender stereotypes across the ages: on-line processing in school-age children, young and older adults. Front Psychol 6:1388. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01388

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants who joined the study.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Brescia within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. The post-doc position of Dr. Rosana Carvalho Silva was partly funded by the Psychiatric Hospital “Villa Santa Chiara,” Verona, Italy. The assistant research position of Valentina Menesello is funded by ERA-PerMed PROMPT project [IT-MoH ERP-2020–23671059].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AM, MV, and VM performed the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by MV and AM. Statistical analysis was performed by MV. The first draft of the manuscript was written by RCS, MV, MM, RS, and AM, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Due to the nature of the study, no ethical approval is required. Participants voluntarily confirmed their willingness to participate in the survey and were directed to anonymously complete a self-report questionnaire.

Consent to participate

Not required.

Consent for publication

Not required.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Carvalho Silva, R., Vezzoli, M., Menesello, V. et al. Everything changes but nothing changes: gender stereotypes in the Italian population. Arch Womens Ment Health (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-024-01437-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-024-01437-1