Abstract

Maternal prenatal stress places a substantial burden on mother’s mental health. Expectant mothers in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) have thus far received less attention than mothers in high-income settings. This is particularly problematic, as a range of triggers, such as exposure to traumatic events (e.g. natural disasters, previous pregnancy losses) and adverse life circumstances (e.g. poverty, community violence), put mothers at increased risk of experiencing prenatal stress. The ten-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) is a widely recognised index of subjective experience of stress that is increasingly used in LMICs. However, evidence for its measurement equivalence across settings is lacking. This study aims to assess measurement invariance of the PSS-10 across eight LMICs and across birth parity. This research was carried out as part of the Evidence for Better Lives Study (EBLS, vrc.crim.cam.ac.uk/vrcresearch/EBLS). The PSS-10 was administered to N = 1,208 expectant mothers from Ghana, Jamaica, Pakistan, the Philippines, Romania, South Africa, Sri Lanka and Vietnam during the third trimester of pregnancy. Confirmatory factor analysis suggested a good model fit of a two-factor model across all sites, with items on experiences of stress loading onto a negative factor and items on perceived coping onto a positive factor. Configural and metric, but not full or partial scalar invariance, were established across all sites. Configural, metric and full scalar invariance could be established across birth parity. On average, first-time mothers reported less stress than mothers who already had children. Our findings indicate that the PSS-10 holds utility in assessing stress across a broad range of culturally diverse settings; however, caution should be taken when comparing mean stress levels across sites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals identify the improvement of mental health as a key priority for global health and well-being (Izutsu et al. 2015). Globally, new mothers are amongst the most affected by poor mental health, with estimated depression rates ranging from 15.6 to 19.8% in the perinatal period (Atif et al. 2015). However, the field of maternal mental health is, like most psychological research, limited by a heavy focus on Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich and Democratic countries (WEIRD, Henrich et al. 2010; Atif et al. 2015). As a result, commonly used assessment tools have been developed and normed almost exclusively in high-income settings. This is problematic as exposure to certain environmental stressors and poverty-related insecurities means that experiences of stress are as, if not more, severe in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Furthermore, commonly used mental health assessment tools may not carry the same meaning in cultures which were not involved in scale development and validation, meaning the scale may perform poorly in these settings.

A vital first step for extending the use of assessments of stress to LMICs is to scrutinise their measurement equivalence across settings. Increasingly, such investigations have been carried out in context of maternal and women’s mental health: for example, depression measures, such as Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9), have been examined in terms of its factor structure across expectant mothers in Peru (Smith et al. 2020), Spain (Marcos-Nájera et al. 2018) and China (Zheng et al. 2020),and the Self-Report Questionnaire (SRQ-20) is invariant in mothers across several LMICs (Pendergast et al. 2014). However, even in context of depression and even more so in context of perinatal stress, few studies to date provide much-needed rigorous, multi-site evaluations of commonly used assessment tools.

With this in mind, we examine the factor structure and measurement invariance (MI) of the ten-item version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10, Cohen et al. 1994) across eight LMICs. The original 14-item scale and its abbreviated ten- and four-item version have been used in a range of contexts (including pregnancy, Chaaya et al. 2010; Tanpradit and Kaewkiattikun 2020) and have undergone evaluation of their psychometric properties.

The overwhelming majority of studies assessing the factor structure of the PSS report best fit with a two-factor structure, specifically one latent factor on perceived stress and one on perceived coping (Taylor 2015; Lavoie and Douglas 2012; Reis et al. 2019). Conceptually, the PSS comprises items relating to both negative experiences of stress (e.g. ‘…felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life ‘?) and positive experiences of being able to cope with difficulties (e.g. ‘…felt confident about your ability to handle your personal problems’?). Though some have argued that the two factors are not truly independent but reflect differences in responses due to reverse coded items (e.g. Perera et al. 2017), there is an emerging consensus that items associated with perceived stress and reverse coded items measuring perceived coping are underpinned by separate latent factors (Taylor 2015). The PSS has been translated into over 25 languages (Lee 2012), demonstrating robust psychometric properties (e.g. good internal consistency, Cronbach’s alpha > 0.7, high longitudinal test–retest reliability intraclass correlation coefficient > 0.7). A two-factor structure was reported for versions in Greek (Andreou et al. 2011), Portuguese (Siqueira Reis et al. 2010), German (Bastianon et al. 2020), Chinese (Liu et al. 2020), Spanish (Juárez-García et al. 2021), Thai (Tanpradit and Kaewkiattikun 2020) and Arabic (Ali et al. 2021,). Moreover, MI has been demonstrated across men and women (Liu et al. 2020), longitudinally (Barbosa-Leiker et al. 2013; Reis et al. 2019), age groups and marital status (Ali et al. 2021). Nevertheless, questions regarding the structural and conceptual equivalence of the PSS in non-WEIRD settings remain. Firstly, a rigorous examination of the scale’s MI across multiple LMICs has not been conducted. Furthermore, despite their known vulnerability to mental health problems, expectant mothers situated in LMICs are currently understudied (Staneva et al. 2015), and questions remain whether stress levels differ between first-time mothers making the transition to parenthood compared to mothers of growing families. Addressing these twin gaps, the current study tests the factor structure and MI of the PSS-10 in expectant mothers across eight geographically and culturally diverse settings.

This research forms part of the Evidence for Better Lives Study (EBLS, vrc.crim.cam.ac.uk/vrcresearch/EBLS), which in its first wave has collected data from expectant mothers in Ghana, Jamaica, Pakistan, the Philippines, Romania, South Africa, Sri Lanka and Vietnam. In this analysis we aim to (1) perform confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess whether a previously reported two-factor model provides a good fit and (2) test the assumptions of MI (i.e. configural, metric, scalar) across site and birth parity, to assess whether the same underlying constructs are tapped across study settings and across first- and none-first-time mothers. Such an analysis provides a crucial step when seeking to investigate the cultural universality of the measure and a prerequisite for meaningful cross-site comparisons.

Methods

Participants

Assessments took place as part of the EBLS project, a prospective longitudinal cohort study examining N = 1,208 families across eight LMICs. Ethics boards at each participating institution approved the protocol (Valdebenito et al. 2020).

Expectant mothers were recruited during routine antenatal clinic visits from primary healthcare facilities. They were eligible if they (1) were in the third trimester of pregnancy (29–40 weeks gestation), (2) aged 18 or over and (3) living primarily within the study’s catchment area. On average, 82% of women approached consented to participate. Sample characteristics can be found in Table 1.

Participants’ average age was 28.27 years (range = 18–48 years): women in Ghana, the Philippines, Romania, Sri Lanka and Vietnam on average were older than women in Jamaica, South Africa and Pakistan. Thirty percent of women were nulliparous, with higher rates in Romania (64.9%) and lowest rates in Ghana (15.7%). Education levels ranged from 0 to 20 years completed, with an average of 7.77 years in Pakistan (Anwer et al. 2022) and 12.83 years completed in Romania. For this analysis, data of women expecting twins were retained.

Procedure

Interviews took place from December 2018 to July 2019. Participants provided written or audio-recorded informed consent. During their third trimester of pregnancy, expectant mothers were interviewed by trained fieldworkers using primarily computer-assisted personal interviews (CAPI). Training sessions, to ensure consistency across the study sites and adherence to ethical, health and safety requirements, included the coordination and management tasks, recruitment, sampling, ethics and questionnaire administration. All training resources were combined into a fieldworker manual as a reference during data collection. Interviews were generally conducted alongside routine antenatal care appointments, in a separate room to ensure privacy.

Measures

PSS-10

Participants completed the PSS-10 antenatally as part of an extensive questionnaire battery. The full protocol included questionnaires on participants’ physical and mental health, exposure to adversity, social support, attitudes about their pregnancy and parenting and reproductive history. Participants responded to negative (e.g. ‘…been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly’?) and positive items (e.g. ‘…felt confident about your ability to handle personal problems’?) pertaining to the levels of stress and coping over the past month. Responses were given on a four-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 2 = several days, 3 = more than half the days, 4 = nearly every day). This differed from the usual PSS-10 response scale (five-point Likert scale, 1 = never–5 = very often), to harmonise response options of the PSS-10 with those of the PHQ-9. This harmonisation was necessary, as the full protocol included 19 measures with a total of 212 items, meaning that a retention of each scale’s original response format would have required frequent response-mode-switches. Given varying levels of familiarity with standardised questionnaires, participant literacy and the resulting need to administer the questionnaires verbally, response anchors were harmonised wherever possible.

Secondary outcomes

Participants reported demographic information, including their age, socioeconomic status, highest level of education, number of previous pregnancies and live births.

Translation and piloting

Study materials were translated into the most common languages spoken by participants, guided by the Translation Review Adjudication Pretest Documentation (TRAPD) method (https://europeanvaluesstudy.eu/methodology-data-documentation/survey-2017/methodology/the-trapd-method-for-survey-translation/). Translations followed the same process across study sites to ensure maximal consistency. Where measures had previously been translated into the relevant languages, we conducted our own translations to ensure consistency. In Jamaica, the original English language version was used with slight adaptations. Harmonised translation was achieved through two independent forward translations, which were reviewed by expert panels at each study site. These panels comprised staff who were knowledgeable regarding both the measures employed and cultural views on mental health. Measures were piloted on n = 5–10 women per site to identify and correct issues with comprehension or translation. Pilots revealed minor ambiguities within the full protocol, but not the PSS-10. Prior to the start of data collection, field workers were trained to address potential ambiguities during administration.

Data analysis

Data screening

Data were analysed in Mplus 8.4 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2017). Responses were clustered around the upper and lower end of the response scale, necessitating the dichotomisation of the response options (i.e. 0 = not at all/several days, 1 = more than half the days/nearly every day, Rutkowski et al. 2019). This approach led to a floor effect on one item in the Romanian cohort (1, ‘…been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly’?), which was therefore removed. Therefore, analyses included five negative and four positive items. Analyses applied weighted least squares mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimators as items were ordered categorical.

Measurement invariance across sites

We first assessed the factor structure of the PSS-10 per site. Our model fit criteria were Comparative Fit Index (CFI) > 0.90, Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) > 0.90 and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08 (Brown 2015; Hu and Bentler 1999). We then examined the change in model fit when systematically adding equality constraints. Model comparisons were judged to be invariant if the CFI decreased < 0.02 and the RMSEA increased < 0.003 (Svetina et al. 2020). Since no group was chosen as a reference in designing the study, we used the site appearing first in the alphabet (i.e. Ghana) as our reference group, in which the mean of the latent factor was fixed to 0 and the variance of the latent factor and scale factor were fixed to 1. Where model fit was low, we examined modification indices to identify reasons for poor fit. Assuming a reasonable fit for each group, we proceeded to test the configural invariance across sites (i.e. whether a common factor structure could be found across sites). Next, we examined metric (weak factorial) invariance, by constraining the factor loadings to be equal across groups (i.e. we assessed whether items contributed to each factor in a similar way across sites). Where metric invariance could be established, we proceeded to test scalar (strong factorial) invariance, to compare whether item thresholds were equivalent. If full scalar invariance was not achieved, constraints on the model were released on an item-by-item basis across all groups to identify a partial scalar invariant subset of items. Where full or partial scalar invariance could be achieved, we compared mean levels for each latent factor across sites.

Measurement invariance across birth parity

We split the sample, grouping together women expecting their first (nulliparous group) vs those expecting a subsequent child (multiparous group). As described above, we then conducted CFA and tested configural, metric and scalar invariance across groups.

Results

PSS factor structure by site

The hypothesised two-factor solution presented an acceptable fit for all sites (Table 2). A one-factor model resulted in poor model fit and was therefore not taken forward.

Measurement invariance in prenatal stress across sites

We first assessed the configural invariance by site, yielding a good model fit (RMSEA = 0.058, CI95% = 0.035–0.064; CFI = 0.963; TLI = 0.962). Constraints to test for metric invariance did not significantly reduce the model fit (RMSEA = 0.06, CI95% = 0.048–0.071; CFI = 0.949; TLI = 0.946), however constraints to test for scalar invariance did (RMSEA = 0.127, CI95% = 0.118–0.136; CFI = 0.774; TLI = 0.779). Modification indices suggested to release constraints for six items. However, the three remaining items (2 ‘…were unable to control the important things in your life’?, 3 ‘…felt nervous and ‘’stressed’’’?, 10 ‘…felt difficulties were piling up so high that you could not overcome them’?) still did not produce an acceptable model fit (RMSEA = 0.088, CFI = 0.886; TLI = 0.875). This lack of scalar invariance indicated that mean differences in the latent variable did not capture all shared variance across items, precluding a comparison of mean levels across sites.

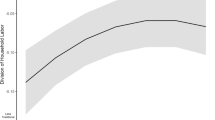

Measurement invariance and mean differences in prenatal stress across birth parity

Testing the two-factor model’s configural invariance across nulliparous and multiparous women revealed a good model fit (RMSEA = 0.043, CI95% = 0.031–0.054; CFI = 0.971; TLI = 0.960). Adding metric (RMSEA = 0.044, CI95% = 0.033–0.054; CFI = 0.966; TLI = 0.959) and scalar (RMSEA = 0.044, CI95% = 0.034–0.054; CFI = 0.963; TLI = 0.958) constraints resulted in an equally good model fit. We therefore compared means of the latent positive and negative factors across groups. Both factors showed significantly higher mean levels in the multiparous compared to the nulliparous group (bnegative = 0.064, SE = 0.014, p < 0.001, bpositive = 0.073, SE = 0.023, p = 0.002).

Discussion

The current study assessed MI of the PSS-10 in N = 1,208 expectant women across eight LMICs. While the detrimental effects of poor mental health for mothers and children are well-documented (e.g. Karam et al. 2016), the literature is skewed towards high-income settings. We found configural and metric MI across sites and configural, metric and scalar MI across birth parity. PSS mean levels were higher for both the positive and the negative factor in mothers who already had at least one child.

Factor structure and response mode

In line with previous studies (Reis et al. 2019; Bastianon et al. 2020; Liu et al. 2020; Juárez-García et al. 2021; Ali et al. 2021), we found strong evidence for a two-factor (one positive, one negative) structure across sites and parity. Responses were clustered towards the extremes of the scale, necessitating dichotomisation of items. As such a bimodal distribution is uncommon for the PSS, future research should investigate possible reasons in context of diverse non-WEIRD settings. Practically, this finding suggests a dichotomised response format may be favourable in LMICs.

Cross-site comparison

We found metric invariance across sites, with items loading onto the latent factors in a similar manner. However, the lack of scalar invariance precluded meaningful cross-site comparisons. The inability to reach this threshold was especially clear for the positive factor (c.f., Santiago et al. 2020). Additionally, some have argued that positive and negative mental health factors represent distinct concepts, meaning that differences in their psychometric properties may be attributable to them capturing different constructs (Phua et al. 2020). Therefore, reporting and analysing scores on both subscales separately may be favourable. We also explored the possibility that differences in response patterns across sites may reflect idiosyncrasies in some positive items (e.g. 5 ‘…felt that things were going your way’?, 8 ‘…felt that you were on top of things’?). However, a review of these items by site-specific experts indicated that these items had not been identified as problematic. Recent investigations from within our group (e.g., on the prenatal attachment index, Foley et al. 2021 and the PHQ-9, Murray et al. 2021), and in the wider literature (Dong and Dumas 2020) also find that the more stringent criteria of MI cannot always be met in cross-cultural research. In the context of perinatal mental health, this perhaps can be attributed to the fact that different ways of coping lead to similar outcomes across cultures (Guardino and Dunkel Schetter 2014). For example, mothers’ acceptance of one’s situation was associated with positive pregnancy outcomes in the USA, and Japanese mothers benefitted more from greater social assurance (Morling et al. 2003). Thus, even where the item structure and factor loadings are equivalent, different endorsement of specific items (e.g. on culturally specific coping styles) may lead to a lack of equivalence in item thresholds.

Comparison across birth parity

We found full scalar MI of the PSS-10 across these two groups. Multiparous mothers showed higher mean levels on both latent factors. One reason for this may be an increased awareness of pregnancy stressors and their own coping ability. In high-income settings, while the transition to parenthood in first-time parents is regarded as the more dramatic change, the addition of subsequent children is associated with higher levels of stress (Gameiro et al. 2009). Further corroborating the link between parity and maternal stress, prenatal exposure to environmental adversity has been shown to affect first-time mothers most severely (Terán et al. 2020). Less attention has been paid to perceived control and self-efficacy; however, these may be higher in multiparous mothers (Loh et al. 2017).

Limitations and strengths

Responses necessitated the use of a dichotomised scale which can inflate estimates of model fit (Rutkowski et al. 2019). This highlights certain drawbacks of Likert scales across different cultures, as cultural factors can contribute to bimodal distributions (Lee et al. 2002). Our other analyses (Foley et al. 2021; Murray et al. 2021) have suggested that a dichotomised administration may be favourable. This is especially true given that questionnaire-based mental health measures developed in high-income settings often show poorer reliability in LMICs (Carroll et al. 2020; Shrestha et al. 2016) and would benefit from site-specific validation against both subjective self-report and objective biological measures (e.g. measures of cortisol).

Harmonising response formats and simplifying responses for participants, we adopted the response scale of the PHQ-9, which uses similar anchors and captures the intensity and frequency. Considering the post hoc dichotomisation in the current and recent studies by our group (Foley et al. 2021; Murray et al. 2021), and in the wider literature (e.g. General Health Questionnaire (GHQ), Goldberg 1988) and the practicalities of administration, future studies may consider dichotomising response options, especially in context of multi-questionnaire, multi-site research. While administrators were trained with the greatest care to ensure reliability, a simplified dichotomised format may serve to further eliminate site differences.

Non-random sampling was applied, limiting the sample’s representativeness. However, across sites several diverse contexts were covered. Our sample sites differed regarding parity and maternal age. Here, differences in family structure need to be acknowledged: while of similar mean age, only 15.7% of women in Ghana were expecting their first child, compared with 64.9% of mothers in Romania. It therefore was not possible to achieve homogeneity across both age and parity, and a lack of MI across sites may in part be attributable to these differences. Furthermore, the potential for cultural differences regarding the understanding of the PSS and the expression of experiences of stress have been highlighted in more qualitative ways in other cross-cultural studies (Ting et al. 2021), and such differences may also have contributed to our results. Lastly, it needs to be noted that formal evaluation of other forms of validity and reliability of the PSS was beyond the scope of this study.

Conclusion and Future Directions

While we have established that the PSS-10 follows a reliable structure across settings, questions remain regarding the optimal response format for use in LMICs. A dichotomised scoring approach may be favourable, given issues with floor and ceiling effects. Our differential findings on the reliability of the positive and the negative subscale may warrant independent reporting of scores on each subscale, to examine possible differential associations of perceived stress and perceived coping with participant outcomes. The PSS-10 showed good configural and metric fit cross-culturally, highlighting its utility for use across a broad range of settings. Caution is advised when comparing mean levels of perceived stress across settings. Regarding birth parity, the PSS-10 passes all tests of conceptual equivalence, enabling mean level comparisons across birth parity.

References

Ali AM, Hendawy AO, Ahmad O, Al Sabbah H, Smail L, Kunugi H (2021) The Arabic version of the Cohen perceived stress scale: factorial validity and measurement invariance. Brain Sci 11(4):419

Andreou E, Alexopoulos EC, Lionis C, Varvogli L, Gnardellis C, Chrousos GP, Darviri C (2011) Perceived stress scale: reliability and validity study in Greece. Int J Environ Res Public Health 8(8):3287–3298

Anwer Y, Abbasi F, Dar A, Hafeez A, Valdebenito S, Eisner M, Sikander S, Hafeez A (2022) Feasibility of a birth-cohort in Pakistan: evidence for better lives study. Pilot Feas Stud 8(1):29

Atif N, Lovell K, Rahman A (2015) Maternal mental health: the missing “m” in the global maternal and child health agenda. In Seminars in Perinatology, Vol. 39, No. 5. WB Saunders, pp. 345–352

Barbosa-Leiker C, Kostick M, Lei M, McPherson S, Roper V, Hoekstra T, Wright B (2013) Measurement invariance of the perceived stress scale and latent mean differences across gender and time. Stress Health 29(3):253–260

Bastianon CD, Klein EM, Tibubos AN, Brähler E, Beutel ME, Petrowski K (2020) Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) psychometric properties in migrants and native Germans. BMC Psychiatry 20(1):1–9

Brown T (2015) Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research, 2nd edn. Guilford Press, London

Carroll HA, Hook K, Perez OFR, Denckla C, Vince CC, Ghebrehiwet S, Ando K, Touma M, Borba CP, Fricchione GL (2020) Establishing reliability and validity for mental health screening instruments in resource-constrained settings: systematic review of the PHQ-9 and key recommendations. Psychiatry Res 291:113236

Chaaya M, Osman H, Naassan G, Mahfoud Z (2010) Validation of the Arabic version of the Cohen Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) among pregnant and postpartum women. BMC Psychiatry 10(1):1–7

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R (1994) Perceived stress scale. Measuring stress: A guide for health and social scientists 10(2):1–2

Cohen S, Williamson G (1998) Perceived stress in a probability sample of the US In: Spacapam S, Oskamp S, editors. The Social Psychology of Health: Claremont Symposium on Applied Social Psychology

Dong Y, Dumas D (2020) Are personality measures valid for different populations? A systematic review of measurement invariance across cultures, gender, and age. Person Individ Differ 160:109956

Foley S, Hughes C, Murray AL, Baban A, Fernando AD, Madrid B, Eisner M (2021) Prenatal attachment: using measurement invariance to test the validity of comparisons across eight culturally diverse countries. Arch Womens Ment Health 24(4):619–625

Gameiro S, Moura-Ramos M, Canavarro MC (2009) Maternal adjustment to the birth of a child: primiparity versus multiparity. J Reprod Infant Psychol 27(3):269–286

Goldberg DP (1988) User’s guide to the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor

Guardino CM, Dunkel Schetter C (2014) Coping during pregnancy: a systematic review and recommendations. Health Psychol Rev 8(1):70–94

Henrich J, Heine SJ, Norenzayan A (2010) The weirdest people in the world? Behav Brain Sci 33(2–3):61–83

Hu LT, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model 6(1):1–55

Izutsu T, Tsutsumi A, Minas H, Thornicroft G, Patel V, Ito A (2015) Mental health and wellbeing in the sustainable development goals. Lancet Psychiatry 2(12):1052–1054

Juárez-García A, Merino-Soto C, Brito-Ortiz JF, Nava-Gómez ME, Monroy-Castillo A (2021) Is it the perceived stress scale (PSS) Undimimensional and invariant? A bifactor analysis in Mexican adults. Curr Psychol 1–15

Karam F, Sheehy O, Huneau MC, Chambers C, Fraser WD, Johnson D, Kao K, Martin B, Riordan SH, Roth M, St-André M, Lavigne SV, Wolfe L, Bérard A (2016) Impact of maternal prenatal and parental postnatal stress on 1-year-old child development: results from the OTIS antidepressants in pregnancy study. Arch Womens Ment Health 19(5):835–843

Lavoie JA, Douglas KS (2012) The Perceived Stress Scale: evaluating configural, metric and scalar invariance across mental health status and gender. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 34(1):48–57

Lee EH (2012a) Review of the psychometric evidence of the perceived stress scale. Asian Nurs Res 6(4):121–127

Lee JW, Jones PS, Mineyama Y, Zhang XE (2002) Cultural differences in responses to a Likert scale. Res Nurs Health 25(4):295–306

Liu X, Zhao Y, Li J, Dai J, Wang X, Wang S (2020) Factor structure of the 10-item perceived stress scale and measurement invariance across genders among Chinese adolescents. Front Psychol 11:537

Loh J, Harms C, Harman B (2017) Effects of parental stress, optimism, and health-promoting behaviors on the quality of life of primiparous and multiparous mothers. Nurs Res 66(3):231–239

Marcos-Nájera R, Le HN, Rodríguez-Muñoz MF, Crespo MEO, Mendez NI (2018) The structure of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 in pregnant women in Spain. Midwifery 62:36–41

Morling B, Kitayama S, Miyamoto Y (2003) American and Japanese women use different coping strategies during normal pregnancy. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 29(12):1533–1546

Murray AL, Hemady CL, Dunne M, Foley S, Osafo J, Sikander S, ..., Walker S (2021) Measuring antenatal depressive symptoms across the world: a validation and cross-country invariance analysis of the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9) in eight diverse low resource settings

Muthén L, Muthén B (1998–2017) Mplus user’s guide (Eighth ed.). Muthén & Muthén

Pendergast LL, Scharf RJ, Rasmussen ZA, Seidman JC, Schaefer BA, Svensen E, ... MAL-ED Network Investigators (2014) Postpartum depressive symptoms across time and place: structural invariance of the Self-Reporting Questionnaire among women from the international, multi-site MAL-ED study. J Affect Disord 167:178–186

Perera MJ, Brintz CE, Birnbaum-Weitzman O, Penedo FJ, Gallo LC, Gonzalez P, … Llabre MM (2017) Factor structure of the Perceived Stress Scale-10 (PSS) across English and Spanish language responders in the HCHS/SOL Sociocultural Ancillary Study. Psychol Assess 29(3):320

Phua DY, Kee MZ, Meaney MJ (2020) Positive maternal mental health, parenting, and child development. Biol Psychiat 87(4):328–337

Reis D, Lehr D, Heber E, Ebert DD (2019) The German version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10): evaluation of dimensionality, validity, and measurement invariance with exploratory and confirmatory bifactor modeling. Assessment 26(7):1246–1259

Rutkowski L, Svetina D, Liaw YL (2019) Collapsing categorical variables and measurement invariance. Struct Equ Model 26(5):790–802

Santiago PHR, Nielsen T, Smithers LG, Roberts R, Jamieson L (2020) Measuring stress in Australia: validation of the perceived stress scale (PSS-14) in a national sample. Health Qual Life Outcomes 18(1):1–16

Shrestha SD, Pradhan R, Tran TD, Gualano RC, Fisher JR (2016) Reliability and validity of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) for detecting perinatal common mental disorders (PCMDs) among women in low-and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 16(1):1–19

Siqueira Reis R, Ferreira Hino AA, Romélio Rodriguez Añez C (2010) Perceived Stress Scale: reliability and validity study in Brazil. J Health Psychol 15(1):107–114

Smith ML, Sanchez SE, Rondon M, Gradus JL, Gelaye B (2020) Validation of the patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for detecting depression among pregnant women in Lima, Peru. Curr Psychol 1–9

Staneva A, Bogossian F, Pritchard M, Wittkowski A (2015) The effects of maternal depression, anxiety, and perceived stress during pregnancy on preterm birth: a systematic review. Women Birth 28(3):179–193

Svetina D, Rutkowski L, Rutkowski D (2020) Multiple-group invariance with categorical outcomes using updated guidelines: an illustration using M plus and the lavaan/semtools packages. Struct Equ Model 27(1):111–130

Tanpradit K, Kaewkiattikun K (2020) The effect of perceived stress during pregnancy on preterm birth. Int J Women’s Health 12:287

Taylor JM (2015) Psychometric analysis of the ten-item perceived stress scale. Psychol Assess 27(1):90

Terán JM, Juárez S, Bernis C, Bogin B, Varea C (2020) Low birthweight prevalence among Spanish women during the economic crisis: differences by parity. Ann Hum Biol 47(3):304–308

Ting RSK, Yong YYA, Tan MM, Yap CK (2021) Cultural responses to Covid-19 pandemic: religions, illness perception, and perceived stress. Front Psychol 12:634863. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.634863

Valdebenito S, Murray A, Hughes C, Băban A, Fernando AD, Madrid BJ, Eisner M (2020) Evidence for Better Lives Study: a comparative birth-cohort study on child exposure to violence and other adversities in eight low-and middle-income countries-foundational research (study protocol). BMJ Open 10(10):e034986

Zheng B, Yu Y, Zhu X, Hu Z, Zhou W, Yin S, Xu H (2020) Association between family functions and antenatal depression symptoms: a cross-sectional study among pregnant women in urban communities of Hengyang city, China. BMJ Open 10(8):e036557

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participating families and Prof Mark Haggard for helpful discussions.

Funding

LK was supported by an ESRC Postdoctoral Fellowship (ES/T008644/1). AM was supported by a British Academy Wolfson Foundation Fellowship. EBLS was supported by the Jacobs Foundation, UBS Optimus Foundation, Fondation Botnar, Consuelo Zobel Alger Foundation, British Academy, Cambridge Humanities Research Grants Scheme, ESRC Impact Acceleration Account Programme, University of Edinburgh College Office for the College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences SFC ODA Global Challenges Internal Fund, University of Cambridge GCRF Quality Research Fund and the Wolfson Professor of Criminology Discretionary Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Katus, L., Foley, S., Murray, A.L. et al. Perceived stress during the prenatal period: assessing measurement invariance of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) across cultures and birth parity. Arch Womens Ment Health 25, 633–640 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-022-01229-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-022-01229-5