Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to examine the effect of dependent care theory-based post-surgical home care intervention on self-care, symptoms, and caregiver burden in primary brain tumor patients and their caregivers.

Methods

A parallel-group randomized controlled trial was conducted with patients who underwent surgery for a primary brain tumor between March 2019 and January 2020 in a tertiary hospital and with caregivers who cared for them at home. Eligible patients and caregivers were determined by block randomization. Outcome measures included validated measures of self-care agency (Self-Care Agency Scale), symptoms and interference by symptoms (MD Anderson Symptom Inventory Brain Tumor-Turkish Form), and caregiver burden (Caregiver Burden Scale). Two-way analysis of variance was used in repeated measurements from general linear models compared to scale scores.

Results

Self-care agency was significantly higher in the intervention group than in the control group in the first and sixth months after surgery (p < 0.05). The severity of the patients’ emotional, focal neurologic, and cognitive symptoms and interference by symptoms were significantly lower in the intervention group than in the control group (p < 0.05). Caregiver burden was significantly lower in the intervention group in the first, third, and sixth months after surgery (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

Dependent care theory-based post-surgical home care intervention increased patients’ self-care and reduced symptoms and their effects. It also reduced the caregiver burden. Dependent care theory can guide the nursing practices of nurses who provide institutional and/or home care services to patients with chronic diseases and their caregivers.

Trial Registration

NCT05328739 on April 14, 2022 (retrospectively registered).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Brain and central nervous system (CNS) cancers are rare [1] but are responsible for significant morbidity and mortality worldwide and have increased in incidence [2]. The age-standardized incidence rate is 3.9 in males and 3.0 in females [3]. In Türkiye, the age-standardized incidence rate is 5.2 (per 100,000) for males and 4.2 (per 100,000) for females [4], which is above the world average.

Whether primary brain tumors (PBTs) are malignant or benign, patients experience many symptoms. Their effects continue after surgical treatment. Symptoms trigger each other, and more than one symptom disrupts individuals’ physical, cognitive, and psychosocial functions in a way that affects daily life [5,6,7]. Many challenges remain in the effective management of symptoms in adults with brain tumors [8]. Patients may become dependent on others before and after surgery [5]. When the caregiver burden studies in caregivers of patients with PBT were reviewed, it was found that the neuropsychological status of the patients [9], activities of daily living [10], and economic inadequacies [11] increase the caregiver burden and cause many problems in caregivers [12]. Studies conducted with PBT patients and their caregivers have suggested that effective interventions should be developed to meet their needs [13,14,15].

Orem’s Self-Care Deficit Nursing Theory (SCDNT) is one of the most frequently used theories in nursing practice [16]. Dependent Care Theory (DCT), one of the four central theories of SCDNT, provides the opportunity to evaluate patients and caregivers. The role of nurses in self-care/dependent care practices becomes crucial in the shortening of hospitalization times and the transfer of care of individuals from institutions to society [17]. Nurse-led intervention programs that evaluate PBT patients and their caregivers in their own homes after surgical treatment are limited [18,19,20,21,22]. It is emphasized that it is essential to provide appropriate interventions to patients and caregivers in meeting the needs of care-related individuals. Providing information appropriate to individuals’ experiences and needs in providing care and support can increase success [23, 24]. No studies based on DCT were found that evaluated patients with PBT and their caregivers. PBTs are a disease that can cause the emergence of many intense and unmet therapeutic self-care demands in the patient and caregivers. Patients and their caregivers must be taught how to provide and maintain appropriate care in their homes and the pathological problems and harmful effects that may arise during treatment and care [25]. This study aimed to examine the effect of dependent care theory-based post-surgical home care intervention on self-care, symptoms, and caregiver burden in primary brain tumor patients and their caregivers.

We hypothesized that the dependent care theory-based post-surgical home care intervention could improve self-care, decrease patients’ severity of symptoms and interference by symptoms, and caregiver burden for patients with PBT and their caregivers.

Methods

Study design

This study was a parallel-group randomized controlled trial (ClinicalTrial.gov; registration number: NCT05328739).

Participants

Criteria for patients inclusion in the study were living within the region’s borders, being aged ≥ 18 years old, being diagnosed with PBT (glial or meningeal and grade I–III), having KPS ≥ 50 points, and being able to read and communicate. Patients’ exclusion criteria were diagnosed as having metastatic brain tumor, a pituitary adenoma, having undergone emergency surgery, having a biopsy, and being in grade IV. Caregiver inclusion criteria were age ≥ 18 years, providing primary care for patients, and being able to read and communicate. Criteria for terminating the research process for participants were wanting to leave the research process, meeting one of the criteria for exclusion from the sample after the surgery, spending the home care and follow-up process in another province, and/or being unable to reach the individual.

Sample size

G*Power 3.1.9.2 was used to calculate the sample size for this study. A similar study was used to determine the study’s sample [26]. The power of the study was 0.903 at the α = 0.05 level and 0.816 effect size. The study was conducted with 18 patients and 18 caregivers (Fig. 1).

Randomization

Block randomization was used to balance the sample size between groups over time. A quadruple block structure consisting of six combinations was created. According to this structure created by an independent person from the research, intervention and control groups were generated by specifying which group the registered participant belonged to the researcher conducting the research process. Blinding was provided because patients and caregivers who met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate in the study did not know which group they would join [27].

Post-surgical home care intervention program

This program comprised the transition home after discharge and the 6-month post-surgical period for patients who underwent surgery for PBT and their caregivers. The program was constructed based on dependent care theory and had three purposes (Table 1). The first was to regulate, protect, and raise self-care agency; the second was to reduce the severity of symptoms and interference by symptoms; and the third was to reduce caregiver burden. In order to ensure the continuity of post-surgical care at home in 6 months, a supportive-developmental nursing system based on the DCT was used. This system, which includes education, counseling, and nursing care, focuses on goals. The content of the training booklet was created by determining the topics related to the postoperative self-care/dependent care demands and the practices that could meet them. The booklet for patients with PBT and their caregivers was prepared based on the literature on home care [17, 25, 26, 28,29,30,31]. The booklet, submitted for expert opinion, was found suitable by experts in the field (W = 0.267; p = 0.230). Nursing care was given to the patient and caregiver in line with the nursing diagnoses determined according to the self-care/dependent care demands of the patients and caregivers who had undergone craniotomy due to PBT [17, 25, 26, 28,29,30].

Procedures

Patients and caregivers were recruited at the same time between March 2019 and January 2020 in a tertiary hospital in Türkiye. After the decision for surgery, the patient and caregiver were interviewed and informed about the study, the Informed Voluntary Consent Form-IVCF was filled out, and initial data were collected (preoperative period-T0). Block randomization assigned patients and caregivers to intervention and control groups. Patients and caregivers in the control group received routine care in the hospital until discharge. Three home visits were made to collect the data of patients and caregivers in the first (postoperative period-T1), third (postoperative period-T2), and sixth (postoperative period-T3) months of surgery after discharge, but no intervention was made.

Patients and caregivers in intervention groups received training and a training booklet until patients were discharged. This total time lasted 90–120 min. In order to prepare the patient and caregiver for the transition home, training was provided on the self-care/dependent care demands that may be encountered in the first week at home and how they can be met, where care can be given and necessary environmental arrangements, what to do in emergencies and drug treatment. Two home visits were made within the first month, planned for education, counseling, and nursing care. The first home visit was made the week after discharge (10–18 days after surgery). At this stage, the patient and caregiver were evaluated in their environment, and nursing care was given for the needs and problems determined for the first visit. At the second home visit (30–40 days after surgery), planned and made at the end of the first month, the patient and caregiver were evaluated in their environment, and nursing care was given for the needs and problems determined for the second visit. Then, in the home visits made once in the second, third, and fourth months, the patient and caregiver were evaluated in their environment similarly, and nursing care was given for the needs and problems determined for that visit. No home visits were made between the fourth and sixth months, but telephone counseling was provided when necessary. The last home visit was made for the sixth-month measurements and goodbye to the patient and caregivers. In this process, nursing care was given to the patient and caregiver per the nursing diagnoses determined according to patients’ and caregivers’ self-care/dependent care demands.

Measurements

Self-care was measured using the Self-Care Agency Scale (SCAS) [32], and the severity of symptoms in patients with PBT and the life-threatening condition of patients were measured using the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory Brain Tumor-Turkish Form (MDA-BTSETr) [33]. Caregiver burden was measured using the Caregiver Burden Scale (CBS) [34]. These measurement tools are valid and reliable tools suitable for Turkish society. Cronbach’s alpha value of the measurement tools in this study was acceptable, at 0.94 in patients and 0.91 in caregivers for SCAS; 0.85 and 0.88 for MDA-BTSETr and CBS, respectively. The Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS) [35] allows the evaluation of the patients’ individual and medical care needs to obtain information about symptom severity and level of function at work and home.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS 26 was used for statistical analyses. Descriptive statistics are given as number of units (n), percentage (%), and mean ± standard deviation. The normal distribution of the data of numerical variables was evaluated with the Shapiro–Wilk test of normality and Q-Q graphs. Homogeneity of variances was evaluated with the Levene test, and two-way analysis of variance was used in repeated measurements from general linear models in comparison of scale scores between T0, T1, T2, and T3 between groups and within groups. Bonferroni correction was applied when comparing the main effects. Comparisons between categorical variables and groups were evaluated with Fisher’s exact test in 2 × 2 and r × c tables [36], p < 0.05 value was considered statistically significant.

Results

Participant characteristics

Comparisons of patients’ and caregivers’ descriptive and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 2; there were no differences between the two groups (p > 0.05), indicating that they were comparable.

Intervention effects for primary brain tumor patients

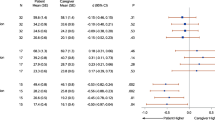

Comparison of the mean scores of SCAS of the patients in the control and intervention groups according to the measurement times are shown in Table 3. At baseline, SCAS scores for patients in the intervention and control groups were similar (p > 0.05). General linear model analysis showed a significant effect of group on SCAS score (p = 0.45) and the effect of time (p = 0.006). SCAS scores for patients in the intervention group were higher than in the control group in the first and sixth months after the surgery (p < 0.05). These results suggest that patients in the intervention group had increased SCAS scores after the intervention.

Comparisons of the mean scores of the severity of symptoms and interference by symptoms of the patients in the control and intervention groups according to the measurement times are shown in Table 4. General linear model analysis showed a significant effect of time (p < 0.001) on emotional and focal neurologic symptom scores. Significant effects of group (p = 0.047), the effect of time (p < 0.001), and group x time (p = 0.008) on cognitive symptoms were also significant. Significant effects of time (p < 0.001) and group x time (p = 0.043) on interference by symptoms scores were also significant. These results suggest that patients in the intervention group had decreased severity symptoms and interference by symptoms scores after the intervention.

Intervention effects for caregivers

Comparisons of the mean scores of SCAS and CBS according to the measurement times of the caregivers in the control and intervention groups are shown in Table 5. General linear model analysis showed no significant effects of the group, the effect of time, and group x time (p > 0.05) on the SCAS score. These results suggest that the intervention does not affect caregivers’ SCAS scores. Significant effects of group (p = 0.005), the effect of time (p < 0.001), and group x time (p < 0.001) on CBS scores were also significant. According to model statistics, in the change of the mean scores of CBS over time, the decrease in the intervention group’s scores was higher than that of the control group (p < 0.001).

Discussion

In this study, we examined the effect of a post-surgical home care intervention based on dependent care theory on patients with primary brain tumors and their caregivers and found that self-care increased and the severity of symptoms and interference by symptoms and caregiver burden decreased.

Our results showing increased patients’ self-care ability are similar to previous studies [20, 37,38,39]. The difference between this study and others is that the home care intervention, based on the dependent care theory, simultaneously supports the patient and the caregiver. In addition, it is thought that evaluating individuals in their environment through home visits, determining their care needs, and systematically planning and implementing education, counseling, and nursing care positively affect self-care skills.

Many patients with primary brain tumors experience symptoms before and after treatment that interfere with daily activities, mood, and tasks, including household chores, relationships with other people, walking, and enjoyment of life [6, 9, 33, 40,41,42,43]. It is essential because the symptoms are important severity and interference in individuals’ lives target therapeutic self-care needs and affect self-care/dependent care ability and nursing practices. After the intervention, the severity of emotional, focal neurological, and cognitive symptoms and interference by symptoms decreased in patients, similar to the previous report [26]. These results suggest that the resources created for patients and caregivers within the scope of the home care program, which is the road map in the study, are adequate.

After our intervention, there was no significant difference in caregivers’ self-care agency. This result is consistent with the results of Deek et al. [44]. This may be due to sample differences and intervention differences. Our results showing a decrease in the CBS of caregivers were similar to previous studies [45, 46], but there were also study results that were not similar [19, 22]. The difference between this study and others is that the home care intervention supports the patient and caregiver simultaneously. In the home care intervention, it was prioritized to develop the skills and abilities of caregivers, such as determining and meeting the needs of the patient, determining care priorities, applications for emergencies, evaluating the home environment and making the necessary arrangements, using support resources, and protecting and developing their own self-care agency. The significant decrease in the postoperative CBS scores of the caregivers in the intervention group compared to the control group showed that home care programs targeting both the patient and the caregivers contributed positively.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. In the region where the research was conducted, brain surgeries were performed in a single center. Since both the patient and their caregivers were evaluated in the study, individuals who met the conditions of the research criteria at the same time were included in the study. Therefore, the research was conducted with a small group.

Conclusion

Dependent care theory-based post-surgical home care intervention increased patients’ self-care and reduced symptoms and their effects. It also reduced the caregiver burden. Dependent care theory can guide the nursing practices of nurses who provide institutional and/or home care services to patients with chronic diseases and their caregivers.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NK et al (2023) Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin 73:17–48. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21763

GBD (2016) Brain and Other CNS Cancer Collaborators (2019) Global, regional, and national burden of brain and other CNS cancer, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol 18(4):376–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30468-X

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL et al (2021) Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 71(3):209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660

Türkyılmaz M, Oruç Hamavioğlu Eİ, Dündar S (2022) Türkiye cancer statistics 2018. Tolunay T, Kaygusuz S, Keskinkılıç B (eds) Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Health General Directorate of Public Health p.30

Krajewski S, Furtak J, Zawadka-Kunikowska M et al (2023) Functional state and rehabilitation of patients after primary brain tumor surgery for malignant and nonmalignant tumors: a prospective observational study. Curr Oncol 30(5):5182–5194. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30050393

Nassiri F, Suppiah S, Wang JZ et al (2020) How to live with a meningioma: experiences, symptoms, and challenges reported by patients. Neurooncol Adv 2(1):vdaa086. https://doi.org/10.1093/noajnl/vdaa086

Tankumpuan T, Utriyaprasit K, Chayaput P (2015) Itthimathin P (2015) Predictors of physical functioning in postoperative brain tumor patients. J Neurosci Nurs 47(1):E11-21. https://doi.org/10.1097/JNN.0000000000000113

Zhang R, Wang DM, Liu YL et al (2023) Symptom management in adult brain tumours: a literature review. Nurs Open 10(8):4892–4906. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.1795

Kanter C, D’Agostino NM, Daniels M (2014) Together and apart: providing psychosocial support for patients and families living with brain tumors. Support Care Cancer 22(1):43–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-1933-1

Sherwood PR, Given BA, Given CW et al (2006) Predictors of distress in caregivers of persons with a primary malignant brain tumor. Res Nurs Health 29(2):105–120. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20116

Bayen E, Laigle-Donadey F, Proute M et al (2017) The multidimensional burden of informal caregivers in primary malignant brain tumor. Support Care Cancer 25:245–253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3397-6

Sharma A, Kaur S, Tewari MK, Singh A (2014) Extent of the burden of caregiving on family members of neurosurgical inpatients in a tertiary care hospital in north India. J Neurosci Nurs 46(1):E3-9. https://doi.org/10.1097/JNN.0000000000000030

Heckel M, Hoser B, Stiel S (2018) Caring for patients with brain tumors compared to patients with non-brain tumors: experiences and needs of informal caregivers in home care settings. J Psychosoc Oncol 36(2):189–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2017.1379046

Piil K, Jakobsen J, Christensen KB et al (2018) Needs and preferences among patients with high-grade glioma and their caregivers - a longitudinal mixed methods study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 27(2):e12806. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12806

Scaratti C, Leonardi M, Saladino A et al (2017) Needs of neuro-oncological patients and their caregivers during the hospitalization and after discharge: results from a longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer 25(7):2137–2145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3619-6

Meleis AI (2012) Theoritical nursing development & progress. Wolters Kluwer Health, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Taylor SG, Renpenning KM (2011) Self-care science, nursing theory and evidence-based practice. Springer Publishing Company

Boele FW, Rooney AG, Bulbeck H, Sherwood P (2019) Interventions to help support caregivers of people with a brain or spinal cord tumour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 7(7):CD012582. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012582.pub2

Dionne-Odom JN, Azuero A, Lyons KD (2015) Benefits of early versus delayed palliative care to ınformal family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer: outcomes from the ENABLE III Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol 33(13):1446–52. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.58.7824

Liu C, Zhang X, Liu X et al (2020) Application of Orem’s self-care theory in the nursing of patients after craniocerebral tumor surgery and its impacts on their self-care ability and mental state. Int J Clin Exp Med 13(10):8000–8006

Pace A, Villani V, Di Pasquale A (2014) Home care for brain tumor patients. Neurooncol Pract 1(1):8–12. https://doi.org/10.1093/nop/npt003

Reblin M, Ketcher D, Forsyth P, Mendivil E, Kane L, Pok J, Meyer M, Wu YP, Agutter J (2018) Outcomes of an electronic social network intervention with neuro-oncology patient family caregivers. J Neurooncol 139(3):643–649. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-018-2909-2

Petruzzi A, Finocchiaro CY, Lamperti E, Salmaggi A (2013) Living with a brain tumor: reaction profiles in patients and their caregivers. Support Care Cancer 21(4):1105–1111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1632-3

Sherwood PR, Cwiklik M, Donovan HS (2016) Neuro-oncology family caregiving: review and directions for future research. CNS Oncol 5(1):41–48. https://doi.org/10.2217/cns.15.43

Repenning K, Taylor SG, Pickens JM (2016) Foundation of professional nursing: care of self and others. Springer Publishing Company, LLC

Baksi Şimşek A (2013) Examination of adaptive and non-adaptive behaviours of the patients with primary brain tumor by Roy Adaptation Model, the effect of education on symptom and coping. Dissertation, Dokuz Eylul University

Nahcivan N (2014) Quantitative research designs. In: Erdoğan S, Nahcivan N, Esin MN (Eds) Research in nursing: process, practice and critical. Nobel Medical Publishing. p.87–130

American Brain Tumor Association (2018) About brain tumors, a primer for patient and caregivers. Retrieved from https://www.abta.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/About-Brain-Tumors_2020_web_en.pdf

Karadakovan A, Özbayır T (2014) Brain tumors In: Karardakovan A, Eti Aslan F (Eds) Care in internal and surgical diseases .Academic Medical Publishing. p. 1184–1197.

Wilkson J, Barcus L (2018) Pearson handbook of nursing diagnoses. Kapucu S, Akyar I, Korkmaz F (Translation editors), (11th edition) Pelikan Publishing.

Kaya H (2014) Care in patients with intracranial tumors. In: Trans (ed) Topçuoğlu MA, Durna Z, Karadakovan A. Nobel Medical Bookstores, Neurological sciences nursing, Evidence-Based Practices, pp 331–356

Nahcivan NO (2004) A Turkish language equivalence of the exercise of self-care agency scale. West J Nurs Res 26(7):813–824

Baksi A, Dicle A (2010) MD The validity and reliability of MD Anderson Symptom Inventory-Brain Tumor. Dokuz Eylül Univer Nurs Faculty Electronic J 3(3):123–136

İnci FH, Erdem M (2008) Validity and reliability of the burden interview and its adaptation to Turkish. J Anatolia Nurs Health Sci 11(4):85–95

Schaafsma J, Osoba D (1994) The Karnofsky performance status scale re-examined: a cross-validation with the EORTC-C30. Qual Life Res 3:413–424

Mehta CR, Patel NR (1986) A hybrid algorithm for Fisher’s exact test in unordered rxc contingency tables. Commun Statistics-Theory Methods 15(2):387–403

Altın Çetin A (2020) The effect of telephone symptom triage protocol on symptom management, quality of life and self care agency in patients with cancer who applied systemic treatment. Dissertation, Akdeniz University

Ceylan, H. (2020). The effect of web-based education based on Self-Care Deficiency Theory on self-care power, self-efficacy and perceived social support in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis. Dissertation, Akdeniz University

Mohammadpour A, Sharghi NR, Khosravan S et al (2015) The effect of a supportive educational intervention developed based on the Orem’s self-care theory on the self-care ability of patients with myocardial infarction: a randomised controlled trial. J Clin Nurs 24(11–12):1686–1692. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12775

Cahill JE, Lin L, LoBiondo-Wood G (2014) Personal health records, symptoms, uncertainty, and mood in brain tumor patients. Neurooncol Pract 1(2):64–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/nop/npu005

Dhandapani M, Gupta S, Mohanty M et al (2017) Prevalence and trends in the neuropsychological burden of patients having ıntracranial tumors with respect to neurosurgical intervention. Ann Neurosci 24(2):105–110. https://doi.org/10.1159/000475899

Schepers VPM, van der Vossen S, van der Berkelbach Sprenkel JW et al (2018) Participation restrictions in patients after surgery for cerebral meningioma. J Rehabil Med 50(10):879–885. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-2382

Armstrong TS, Mendoza T, Gning I et al (2006) Validation of the MD Anderson symptom inventory brain tumor module (MDASI-BT). J Neurooncol 80(1):27–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-006-9135-z

Deek H, Chang S, Newton PJ et al (2017) An evaluation of involving family caregivers in the self-care of heart failure patients on hospital readmission: randomised controlled trial (the FAMILY study). Int J Nurs Stud 75:101–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.07.015

Bayrak B (2019) The effect of training provided to home caregivers of patients who received hemodialysis treatment upon care burden and patients’ quality of life. Dissertation, Karadeniz Technical University

Bitek DE (2019) The effect of post-stroke discharge training and telephone counseling on the functional status of patients and the burden of care for their relatives. Dissertation, Trakya University

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients, their caregivers, and the hospital staff who contributed to this study.

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D. D. and H. Z. made substantial contributions to the conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; D. D. carried out the implementation phase of the study; D. D. and H. Z. involved in drafting of the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and D. D. and H. Z. gave the final approval of the version to be published. Each author has participated sufficiently to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Academic Committee Decision (2019/1) and Erciyes University Clinical Research Ethics Committee (2019/179). All participants provided written informed consent, and the trial was registered in the Clinical Trial Registry at NCT05328739 on April 14, 2022.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Informed consent for publication was obtained from all participants.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dağdelen, D., Zincir, H. Effects of dependent care theory-based post-surgical home care intervention on self-care, symptoms, and caregiver burden in patients with primary brain tumor and their caregivers: a randomized controlled trial. Support Care Cancer 32, 296 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-024-08488-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-024-08488-1