Abstract

Aim

Radiation-induced oral mucositis (RIOM) is the most frequent side effect in head and neck cancer (HNC) patients treated with curative radiotherapy (RT). A standardized strategy for preventing and treating RIOM has not been defined. Aim of this study was to perform a real-life survey on RIOM management among Italian RT centers.

Methods

A 40-question survey was administered to 25 radiation oncologists working in 25 different RT centers across Italy.

Results

A total of 1554 HNC patients have been treated in the participating centers in 2021, the majority (median across the centers 91%) with curative intent. Median treatment time was 41 days, with a mean percentage of interruption due to toxicity of 14.5%. Eighty percent of responders provide written oral cavity hygiene recommendations. Regarding RIOM prevention, sodium bicarbonate mouthwashes, oral mucosa barrier agents, and hyaluronic acid-based mouthwashes were the most frequent topic agents used. Regarding RIOM treatment, 14 (56%) centers relied on literature evidence, while internal guidelines were available in 13 centers (44%). Grade (G)1 mucositis is mostly treated with sodium bicarbonate mouthwashes, oral mucosa barrier agents, and steroids, while hyaluronic acid-based agents, local anesthetics, and benzydamine were the most used in mucositis G2/G3. Steroids, painkillers, and anti-inflammatory drugs were the most frequent systemic agents used independently from the RIOM severity.

Conclusion

Great variety of strategies exist among Italian centers in RIOM management for HNC patients. Whether different strategies could impact patients’ compliance and overall treatment time of the radiation course is still unclear and needs further investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Head and neck cancer (HNC) represents the seventh most common cancer worldwide [1]. They account for different histologies (mainly squamous cell carcinoma but also salivary glands tumors, undifferentiated carcinoma, melanoma, lymphomas…) located in different head and neck subsites (oral cavity, pharyngeal axis, larynx, paranasal sinuses, and salivary glands).

Radiotherapy (RT) is a cornerstone treatment for cancers of the head and neck region [2]. It is indicated either as an exclusive treatment or in patients at high risk of local recurrence after surgery. The total dose of RT ranges from 45 to 70 Gy, administered mainly using a standard fractionation schedule (1.8–2.2 Gy/fraction, 1 fraction/day for 5 fractions/week). Platinum-based concurrent chemotherapy is indicated in patients with locally advanced stage tumors (stage III or IV according to NCCN guidelines) in the presence of pathological features such as positive surgical margins and/or extracapsular extension in the postoperative setting [3].

Radiation-induced oral mucositis (RIOM) is the most frequent and dose-limiting radiation-related side effect in the setting of patients treated with curative RT for HNC [4, 5]. Pain and severe dysphagia due to RIOM may lead to significant patient weight loss with an overall worsening of his/her performance status. Most importantly, RIOM often causes the temporary interruption of the radiation course which has been demonstrated to decrease the efficacy of the radiation treatment [6, 7].

Different scales for grading the severity of RIOM are currently used in clinical practice, as a guide for the radiation oncologist in undertaking preventive and therapeutic strategies [8]. For instance, the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG)/European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer scale considers either the anatomical changes of the oral mucosa (from grade 0 with no toxicity to grade 4 mucosal ulceration/hemorrhage and necrosis) or the level of pain reported by patients caused by RT [9]. Instead, the Common Terminology Criteria Adverse Event (CTCAE V5.0, November 27, 2017) scale distinguishes different cases, from asymptomatic ones (grade 1), which do not require any medical intervention, to more serious cases requiring urgent nutritional and/or medical intervention (grade 4) or leading to the death of the patient (grade 5).

Despite its clinical relevance, a standardized strategy for preventing and treating RIOM has not been defined yet [10,11,12,13,14]. Recommendations provided by cooperative group of experts have been published to guide the management of RIOM in daily clinical practice [15,16,17]. Nevertheless, to date, strategies applied to manage RIOM remain at institutional and/or personal levels according to internal guidelines and professional’s expertise.

Aim of the present work is to perform a real-life survey on how RIOM is managed among Italian radiation therapy centers. Moreover, whether the volume of treated patients could have an impact on the single-institution strategy has been also analyzed.

Materials and methods

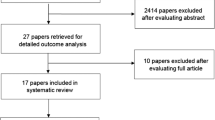

On 11 May 2022, an online survey composed of a total of 53 questions, including both multiple-choice and open-ended ones, was administered through a personnel contact to radiation oncologists working in 25 different RT centers across Italy.

The survey was composed of 40 questions divided into three sections: (i) retrospective analysis of patients with HNC treated in 2021 in each center; (ii) strategies generally used for the prevention of RIOM; and (iii) strategies used for the treatment of RIOM in daily clinical practice. The full text of the survey is available in the supplementary materials section (supplementary material S1). All the participants gave their consent to the publication and the use of collected data for scientific purposes.

In the retrospective analysis, oncologic treatment characteristics (in terms of radiation technique and concurrent systemic treatments), overall RT treatment time, and treatment interruptions were collected.

Among general strategies applied to prevent and treat RIOM, data on institutional organization (professionals who manage RIOM, availability of dedicated nurses, and/or access to supportive care, nutrition, speech, and psychological services) and use of a standardized approach (RIOM data collection using validated scales and adherence to internal and/or published guidelines) has been also collected. The approach (prophylactic or therapeutic intervention) to artificial nutrition (both enteral and parenteral) was investigated.

All agents used in daily clinical practice both in the prevention and treatment phase of RIOM have been collected and gathered (when feasible).

Data will be presented as mean/median across the responders (section i) and counts (sections ii and iii). Moreover, an arbitrary cut-off of 50 treated patients/year has been used to define centers as “high-volume” (>50 patients/year) or “low-volume” (< 50 patients/years) centers. Results were divided accordingly to compare the two groups in terms of treatment strategies.

Results

All the 25 contacted RT centers responded to the survey and all sections have been completed. Dividing according to geographical location, seven centers are located in northern Italy, five in central Italy, and the remaining in southern Italy.

Section 1: questionnaire

Retrospective analysis

In 2021, a total of 1554 patients with HNC were treated in the 25 centers participating (median 54, IQR: 20–70). The majority (median 91%) of the treatments had a curative intent (36% of them postoperative), while the others were administered for palliative intent. In most cases (mean 84%), patients underwent intensity-modulated RT (IMRT) technique. One center used a 3D RT technique for all patients, while the remaining 24 centers applied this technique on a median of 17% of patients.

Platinum-based chemotherapy was the most (71% of patients) frequently concurrent treatment, with a median of 43% and 29% of patients treated using a weekly and 3-weekly schedule, respectively. Cetuximab was used in 17 centers to treat a mean of 10% of patients.

The median value of median overall treatment time was 41 days (IQR: 35–45). The mean percentage of patients who interrupted treatment due to RT-related toxicity was 14.5% (data available for 19 centers). A median of 6% (IQR: 3.5–15) of patients required enteral nutrition.

Strategies for RIOM prevention

In almost all centers (96%), HNC patients are visited at least once a week during the RT course. Quality of life questionnaires were distributed to the patients in 16% of centers and the collection of pain data on a quantitative scale is provided in 80% of cases. In-treatment toxicity is collected systematically at least once a week (84% of facilities), using the CTCAE scale (38%), the RTOG scale (19%), or both (43%). In the case of concurrent chemotherapy, enteral nutrition is proposed only to patients with significant weight loss during the RT course and to all fragile patients in 48% and 20% of cases, respectively (20% in both situations). All but three centers (which never use parenteral nutrition) used similar criteria to select patients candidates for parenteral nutrition.

The majority of the centers (80%) provide patients with written oral cavity hygiene recommendations. Among 17 centers (data not available for three centers), accurate daily oral cavity cleaning (52%), use of mucosal barrier agents (47%), and pre-treatment dentistry evaluation (35%) were the most frequent recommendations.

About half of the centers (52%) use internal guidelines for RIOM prevention, and 15 centers referred to literature evidence and/or expert recommendations (60% of recommendations provided by the Associazione Italiana di Radioterapia ed Oncologia Clinica — AIRO). Eighteen (72%) centers provided written general recommendations for RIOM prevention. Data from 14 centers (data not available for four centers) accurate oral cavity cleaning (60%), oral mouthwashes with bicarbonate (47%), and pre-treatment dentistry evaluation (40%) were the most frequent pieces of advice.

All but four centers also suggest the use of topic and/or systemic agents to prevent RIOM (Fig. 1).

Six centers produce galenic products (a mixture of different agents) produced by their pharmacy.

Strategies for RIOM treatment

The radiation oncologist manages the acute RIOM toxicity in all but one center: medical oncologists and pain specialists also support patient care in 12 (48%) and eight centers, respectively. In 16 (64%) centers, hospitalization for supportive care is allowed. Moreover, different services contribute to taking care of patients during the radiation treatment course: 13 (52%) centers have a nurse dedicated to HNC patients, 18 (72%) centers have a supportive therapy service for pain management, 22 (88%) centers have nutritional consultants, 14 (56%) centers have a speech therapy service for the management of mechanical dysphagia while 18 (72%) have a psycho-oncology service as well.

Fourteen (56%) centers base treatments of RIOM on literature evidence, while internal guidelines are present in 13 centers (44%). Eight centers (32%) did not follow either internal guidelines or literature data. Galenic agents were produced by pharmacies of seven institutions.

The frequency of topic and systemic agents used to treat RIOM is reported in Figs. 2 and 3, respectively.

The frequency of topic and systemic agents used to treat RIOM according to the increasing grade of mucositis (from G1 to G3) is reported in Fig. 4 and Fig. 5, respectively.

Volume of treated patients

To investigate the impact of the “volume of patients” (number of patients treated per year) on the management of RIOM, we classified centers as “low-volume” (< 50 patients/years) and “high-volume” (> 50 patients/years). Twelve and 13 centers gathered low- and high-volume cohorts, respectively. The mean number of patients treated in each group was 21 (IQR: 10–25) and 96 (IQR: 66–136) for low- and high-volume centers, respectively.

Differences in terms of RT technique, concurrent systemic agents, center supportive network, and prevention/treatment strategies between high- and low-volume centers are reported in Table 1.

The mean value of the overall treatment time resulted to be 42 (IQR: 38–45) and 40 (IQR: 30–45) days in low- and high-volume centers, respectively. The percentage of patients who interrupted the RT treatment according to low- and high-volume classification was 16% and 13%, respectively.

Discussion

Results of the present survey confirmed that a great variety exists among Italian centers in the management (prevention and treatment) of RIOM in the setting of HNC. Of note, the majority of participating centers are provided with different supportive care services and follow internal guidelines and/or literature recommendations. Moreover, a low number of patients (<15%) interrupted the RT treatment course and the mean overall treatment time (41 days) remains quite low.

Despite a large amount of literature data, few agents reached level 1 evidence (results coming from prospective randomized trials and/or meta-analysis) for the management of RIOM. In this scenario, recommendations derived from the consensus of experts and literature review have been published over the last decades. Since 2004, the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer and the International Society of Oral Oncology (MASCC/ISOO) cooperative group published their recommendations on the prevention and treatment of RIOM [18,19,20,21]. Similarly, the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) has periodically published its recommendation since 2009 [15, 22], while an Italian working group endorsed by Associazione Italiana di Radioterapia ed Oncologia Clinica (Gruppo AIRO Inter-regionale Lazio-Abruzzo-Molise) did it in 2019 [17].

Prevention of RIOM

Results of MASCC/ISOO, ESMO, and AIRO recommendations on the prevention of RIOM are summarized in Table 2.

Although supported by low-level evidence of literature, pre-treatment dental evaluation, accurate oral hygiene, and sodium bicarbonate were recommended as standard of care for all adult patients candidates to RT for HNC [15,16,17]. Among the participating centers, two centers do not provide any recommendations to prevent RIOM. Of the remaining 19 (four centers used internal guidelines and details were not provided), sodium bicarbonate was the most frequently used agent (70% of the centers). Data on the use of saline solution were more controversial and were not considered robust enough by the ESMO panelists. In the present survey, only one center advised patients to use saline solution mouthwashes to prevent RIOM.

Benzydamine and low-energy laser (LEL) were recommended for the prevention of RIOM both in patients treated with RT alone and in those treated with chemoradiation [15]. Benzydamine is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug with anesthetic, analgesic, and antiseptic properties. A randomized multicentric randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial demonstrated the efficacy of benzydamine for RIOM prevention [23]. A total of 172 subjects (84 treated with benzydamine and 88 with placebo) were enrolled in 16 North American centers. Benzydamine oral rinse (1.5 mg/ml) or placebo was administered before, during RT, and for 2 weeks from the end of treatment. Results showed that benzydamine produced a 26.3% reduction of mucositis in area under curve compared to placebo (p = 0.009). In particular, benzydamine produces a statistically significant benefit at high RT doses (range 25–37.5 Gy, p < 0.001, and range 37.5–50 Gy, p = 0.006) while it was not effective in patients treated with a slight hypofractionated schedule (>2.2 Gy/fraction). Moreover, 33% of patients treated with benzydamine remained free from ulcers compared to 18% of the placebo group (p = 0.037). Subsequently, four more prospective studies confirmed the efficacy of benzydamine in preventing and reducing the severity of oral mucositis in patients treated with RT [24,25,26,27]. Despite literature evidence and recommendations, only three (12%) centers participating in the present survey stated to have benzydamine in their armamentarium to prevent RIOM.

LEL stimulates the biological responses to repair injuries in healthy tissues and is therefore included among the photobiomodulation therapies. A double-blind randomized trial (low-energy He-Ne laser vs placebo-light treatment) has been published in 1999 by Bensadoun et al. [28]. Thirty patients were enrolled and received a daily application with laser/placebo during the whole course of RT. Results showed that the mean grade of mucositis was significantly lower in patients treated with LEL compared to the control group (grade 1.7 ± 0.26 vs 2.1 ± 0.26, respectively, p = 0.01) with the highest differences observed during the last weeks (from 4th to 7th) of treatment. Moreover, the preventive use of the laser also allowed a significant reduction in oral pain (p = 0.025). Subsequent studies confirmed the efficacy and safety of LEL in adult patients with HNC treated with RT [29,30,31]. A recent position paper published by the World Association of photobiomoduLation Therapy stated that literature evidence is robust enough for the clinical application of LEL to prevent oral mucositis as well as in other settings of treatment-induced toxicities [32]. The reported data led to the inclusion of LEL in all published recommendations and guidelines. Despite this, only one center involved in the present survey uses LEL in its clinical practice. On the contrary, some other products like mucoadhesive agents, chlorhexidine, and sucralfate are used by 10, 1, and 3 centers respectively although not supported by robust data. Of note, oral mucosa barrier and hyaluronic acid-based agents are routinely used by 43 and 26% of centers, respectively, despite not being mentioned within the above-cited published recommendations.

Treatment of RIOM

Results of MASCC/ISOO, ESMO, and AIRO recommendations on the treatment of RIOM are summarized in Table 3.

With regard to strategies aiming to treat RIOM, only topical morphine resulted to be indicated to reduce oral pain. Its use is suggested by either MASCC/ISOO or ESMO recommendations. In a double-blind study, Sarvizadeh et al. randomized 30 patients to treat grade 3 mucositis with topical morphine or a magic mouthwash (magnesium aluminum, hydroxide, lidocaine, and diphenhydramine) for a period of 6 days. On the last day of treatment, mucositis resulted significantly lower in the study group compared to the control cohort (p = 0.045) [33]. Similar results were obtained in a group of 26 patients randomly assigned to receive topical morphine or magic mouthwashes [34]. The duration of severe pain as well as pain intensity resulted lower in patients who received morphine compared to the control group. In the present survey, only one center prescribes topical morphine to treat any grade of mucositis, while other agents like mucoadhesive solution and chlorhexidine are more frequently used.

Hyaluronic acid-based agents are the most frequent products administered by respondents to the survey. A recent meta-analysis showed that it was beneficial for both cutaneous and mucosal radiation-induced side effects (RR: 0.14, 95% CI: 0.04 to 0.45) [35].

Overall treatment time

The occurrence of RIOM causes pain and dysphagia which produce patients’ weight loss and worsening of overall treatment compliance. This aspect may lead to interruptions of the RT course due to uncontrolled side effects. Worsening of oncological outcomes occurs in patients who did not complete the RT treatment course within the planned time. González Ferreira et al. [7] carried out a literature review and showed that delays in RT could produce an average loss of locoregional control ranging from 1.2% per day to 12–14% per week of interruption [7]. Moreover, it has been estimated that a daily dose increase of about 0.6–0.8 Gy would be required to compensate for each day of overall treatment time prolongation. The median value of the overall treatment time (considering both curative and postoperative treatments) reported by centers participating in the present survey resulted to be quite low (41 days, IQR: 35–45). Based on this finding, two main considerations can be done: (1) despite the wide variety of approaches both in preventing and treating RIOM, their impact on the overall treatment course seems to be low and (2) a network of supportive care services (including management of pain, nutrition, and psychological support as well as hospitalization if required) is provided by the majority of RT facilities and this aspect could have done a positive impact on patients’ compliance.

Volume of treated patients

The definition of “high” and “low” volume centers (in terms of hospital volume and/or professional experience) has not been established yet. Nevertheless, it has been demonstrated that the higher the number of patients treated, the better the oncological outcomes. Eskander et al. performed a systematic review of the literature and showed that high-volume hospitals (HR 0.886, 95% CI 0.820–0.956) achieved better results in terms of patients’ long-term survival [36]. In order to quantify the impact of the centers’ experience on the management of RIOM, we performed a subgroup analysis according to the number of treated patients/year using an arbitrary cut-off of 50 patients. Results showed that in high-volume centers, modern RT (namely IMRT) and standard high-dose chemotherapy (3-weekly CDDP) are more frequently used compared to low-volume centers. Similarly, the overall use of published RIOM-related recommendations and availability of supportive care services are slightly higher in high-volume centers for the majority of the considered parameters. Nevertheless, the mean overall treatment time resulted similar between the two groups as well as the number of patients who required a treatment interruption due to RIOM-related toxicity.

Limitations

Several criticisms burdened the present study. Centers participating in the present survey represent only 15% of Italian RT facilities [37]. Nevertheless, the spread of geographical distribution among south (28%), center (20%), and northern Italy (52%), as well as the variability of treated patients/year number (centers at high and low volume), ensure that reported results could be considered representative of how RIOM is nowadays managed among Italian centers in the daily clinical practice. Moreover, several other drugs and agents reported in the literature (i.e., anti-oxidant or immunonutrition) have not been considered in the present analysis. Finally, other factors than mucositis (such as patient’s age, comorbidities, treatment characteristics, and dysgeusia) could impact the patient’s compliance with the radiation treatment.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study reporting an accurate snapshot of the Italian attitude on which agents and drugs are currently used in daily clinical practice to prevent and treat RIOM in Italian RT facilities. Results showed that a great variety still exist despite the availability of national and international recommendations. In this scenario, whether different strategies to manage RIOM could impact patients’ compliance and overall treatment time of the radiation course is still unclear and requires further investigation. Moreover, the presented findings strongly encourage efforts to standardize the RIOM management protocols in daily clinical practice among the RT facilities. To this aim, similar analyses in other countries would be useful to highlight eventual geographical differences.

Abbreviations

- AUC:

-

area under curve

- HNC:

-

head and neck cancer

- IMRT:

-

intensity-modulated radiotherapy

- NSAID:

-

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- LEL:

-

low-energy laser

- RIOM:

-

radiation-induced oral mucositis

- RT:

-

radiotherapy

- QoL:

-

quality of life

References

Cancer today. Accessed April 7, 2023. http://gco.iarc.fr/today/home

Treatment by cancer type. NCCN. Accessed April 7, 2023. https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Bernier J, Cooper JS, Pajak TF et al (2005) Defining risk levels in locally advanced head and neck cancers: a comparative analysis of concurrent postoperative radiation plus chemotherapy trials of the EORTC (#22931) and RTOG (# 9501). Head Neck 27(10):843–850. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.20279

Liu S, Zhao Q, Zheng Z et al (2021) Status of treatment and prophylaxis for radiation-induced oral mucositis in patients with head and neck cancer. Front Oncol 11:642575. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.642575

Maria OM, Eliopoulos N, Muanza T (2017) Radiation-induced oral mucositis. Front Oncol 7:89. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2017.00089

Elting LS, Cooksley CD, Chambers MS, Garden AS (2007) Risk, outcomes, and costs of radiation-induced oral mucositis among patients with head-and-neck malignancies. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 68(4):1110–1120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.01.053

González Ferreira JA, Jaén Olasolo J, Azinovic I, Jeremic B (2015) Effect of radiotherapy delay in overall treatment time on local control and survival in head and neck cancer: review of the literature. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother 20(5):328–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpor.2015.05.010

Sonis ST (2022) Precision medicine for risk prediction of oral complications of cancer therapy—the example of oral mucositis in patients receiving radiation therapy for cancers of the head and neck. Front Oral Health 3:917860. https://doi.org/10.3389/froh.2022.917860

Cox JD, Stetz J, Pajak TF (1995) Toxicity criteria of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 31(5):1341–1346. https://doi.org/10.1016/0360-3016(95)00060-C

Davy C, Heathcote S (2021) A systematic review of interventions to mitigate radiotherapy-induced oral mucositis in head and neck cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 29(4):2187–2202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05548-0

Mallick S, Benson R, Rath GK (2016) Radiation induced oral mucositis: a review of current literature on prevention and management. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 273(9):2285–2293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-015-3694-6

Moslemi D, Nokhandani AM, Otaghsaraei MT, Moghadamnia Y, Kazemi S, Moghadamnia AA (2016) Management of chemo/radiation-induced oral mucositis in patients with head and neck cancer: a review of the current literature. Radiother Oncol 120(1):13–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2016.04.001

Saunders DP, Epstein JB, Elad S et al (2013) Systematic review of antimicrobials, mucosal coating agents, anesthetics, and analgesics for the management of oral mucositis in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 21(11):3191–3207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-1871-y

Judge LF, Farrugia MK, Singh AK (2021) Narrative review of the management of oral mucositis during chemoradiation for head and neck cancer. Ann Transl Med 9(10):916. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-3931

Peterson DE, Boers-Doets CB, Bensadoun RJ, Herrstedt J (2015) ESMO Guidelines Committee. Management of oral and gastrointestinal mucosal injury: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. Ann Oncol 26(Suppl 5):v139–v151. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdv202

Elad S, Cheng KKF, Lalla RV et al (2020) MASCC/ISOO clinical practice guidelines for the management of mucositis secondary to cancer therapy. Cancer. 126(19):4423–4431. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.33100

Le Terapie di Supporto in Radioterapia: una Guida Pratica. » Associazione Italiana di Radioterapia ed Oncologia Clinica. Associazione Italiana di Radioterapia ed Oncologia Clinica. Published January 16, 2019. Accessed April 7, 2023. https://www.radioterapiaitalia.it/linee-guida-raccomandazioni/linee-guida-della-disciplina/le-terapie-di-supporto-in-radioterapia-una-guida-pratica/

Lalla RV, Bowen J, Barasch A et al (2014) MASCC/ISOO clinical practice guidelines for the management of mucositis secondary to cancer therapy. Cancer. 120(10):1453–1461. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28592

Ranna V, Cheng KKF, Castillo DA et al (2019) Development of the MASCC/ISOO clinical practice guidelines for mucositis: an overview of the methods. Support Care Cancer 27(10):3933–3948. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04891-1

Rubenstein EB, Peterson DE, Schubert M et al (2004) Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of cancer therapy-induced oral and gastrointestinal mucositis. Cancer. 100(9 Suppl):2026–2046. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.20163

Keefe DM, Schubert MM, Elting LS et al (2007) Updated clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of mucositis. Cancer. 109(5):820–831. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.22484

Peterson DE, Bensadoun RJ, Roila F, ESMO Guidelines Working Group (2009) Management of oral and gastrointestinal mucositis: ESMO clinical recommendations. Ann Oncol 20(Suppl 4):174–177. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdp165

Epstein JB, Silverman S, Paggiarino DA et al (2001) Benzydamine HCl for prophylaxis of radiation-induced oral mucositis: results from a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Cancer. 92(4):875–885. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(20010815)92:4<875::aid-cncr1396>3.0.co;2-1

Roopashri G, Jayanthi K, Guruprasad R (2011) Efficacy of benzydamine hydrochloride, chlorhexidine, and povidone iodine in the treatment of oral mucositis among patients undergoing radiotherapy in head and neck malignancies: a drug trail. Contemp Clin Dent 2(1):8–12. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-237X.79292

Kazemian A, Kamian S, Aghili M, Hashemi FA, Haddad P (2009) Benzydamine for prophylaxis of radiation-induced oral mucositis in head and neck cancers: a double-blind placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 18(2):174–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2354.2008.00943.x

Kin-Fong Cheng K, Yuen KT, J. (2006) A pilot study of chlorhexidine and benzydamine oral rinses for the prevention and treatment of irradiation mucositis in patients with head and neck cancer. Cancer Nurs 29(5):423–430. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002820-200609000-00012

Rastogi M, Khurana R, Revannasiddaiah S et al (2017) Role of benzydamine hydrochloride in the prevention of oral mucositis in head and neck cancer patients treated with radiotherapy (>50 Gy) with or without chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 25(5):1439–1443. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3548-9

Bensadoun RJ, Franquin JC, Ciais G et al (1999) Low-energy He/Ne laser in the prevention of radiation-induced mucositis. A multicenter phase III randomized study in patients with head and neck cancer. Support Care Cancer 7(4):244–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s005200050256

Bourbonne V, Otz J, Bensadoun RJ et al (2022) Radiotherapy mucositis in head and neck cancer: prevention by low-energy surface laser. BMJ Support Palliat Care 12(e6):e838–e845. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2019-001851

Genot-Klastersky MT, Klastersky J, Awada F et al (2008) The use of low-energy laser (LEL) for the prevention of chemotherapy- and/or radiotherapy-induced oral mucositis in cancer patients: results from two prospective studies. Support Care Cancer 16(12):1381–1387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-008-0439-8

Sandoval RL, Koga DH, Buloto LS, Suzuki R, Dib LL (2003) Management of chemo- and radiotherapy induced oral mucositis with low-energy laser: initial results of A.C. Camargo Hospital. J Appl Oral Sci 11(4):337–341. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-77572003000400012

Robijns J, Nair RG, Lodewijckx J et al (2022) Photobiomodulation therapy in management of cancer therapy-induced side effects: WALT position paper 2022. Front Oncol 12:927685. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.927685

Sarvizadeh M, Hemati S, Meidani M, Ashouri M, Roayaei M, Shahsanai A (2015) Morphine mouthwash for the management of oral mucositis in patients with head and neck cancer. Adv Biomed Res 4:44. https://doi.org/10.4103/2277-9175.151254

Cerchietti LCA, Navigante AH, Bonomi MR et al (2002) Effect of topical morphine for mucositis-associated pain following concomitant chemoradiotherapy for head and neck carcinoma. Cancer. 95(10):2230–2236. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.10938

Tai RZ, Loh EW, Tsai JT, Tam KW (2022) Effect of hyaluronic acid on radiotherapy-induced mucocutaneous side effects: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Support Care Cancer 30(6):4845–4855. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-06902-0

Eskander A, Merdad M, Irish JC et al (2014) Volume-outcome associations in head and neck cancer treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck 36(12):1820–1834. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.23498

I Centri di Radioterapia in Italia » Associazione Italiana di Radioterapia ed Oncologia Clinica. Associazione Italiana di Radioterapia ed Oncologia Clinica. Accessed April 7, 2023. https://www.radioterapiaitalia.it/ricerca-centri-radioterapia/

Acknowledgements

IEO, the European Institute of Oncology, is partially supported by the Italian Ministry of Health (“Ricerca Corrente” and “5x1000” funds). The Division of Radiation Oncology of IEO received research funding from AIRC (Italian Association for Cancer Research) and Fondazione IEO-CCM (Istituto Europeo di Oncologia-Centro Cardiologico Monzino) all outside the current project.

LB received a grant by the European Institute of Oncology-Cardiologic Center Monzino Foundation (FIEO-CCM), outside the current study. MGV was supported by a research fellowship from the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC) entitled “Radioablation ± hormonotherapy for prostate cancer oligo-recurrences (RADIOSA trial): potential of imaging and biology” registered at ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03940235 (accessed on 20th December 2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LB, MP: data collection, methodology, writing original draft; MGV: data analysis, visualization, writing original draft; MZ: data analysis, writing original draft; DA: conceptualization, methodology, writing original draft, supervision. All the remaining authors participated in the survey as responders. All authors had full access to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Given the investigative nature of the study (survey), no ethical approval was required. The study did not involve human or animal participants.

Conflict of interest

The Division of Radiation Oncology of IEO received institutional grants from Accuray Inc. and Ion Beam Applications (IBA). Alterio D. received an uncoditional financial support by Medizioni srl for the current study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Paolo Muto, Umberto Ricardi, and Daniela Alterio are co-last authors.

Supplementary information

ESM 1

(DOCX 16 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bergamaschi, L., Vincini, M.G., Zaffaroni, M. et al. Management of radiation-induced oral mucositis in head and neck cancer patients: a real-life survey among 25 Italian radiation oncology centers. Support Care Cancer 32, 38 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-08185-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-08185-5