Abstract

Purpose

Cancer “curvivors” (completed initial curative intent treatment with surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and/or other novel therapies) and “metavivors” (living with metastatic or chronic, incurable cancer) experience unique stressors, but it remains unknown whether these differences impact benefits from mind–body interventions. This study explored differences between curvivors and metavivors in distress (depression, anxiety, worry) and resiliency changes over the course of an 8-week group program, based in mind–body stress reduction, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and positive psychology.

Methods

From 2017–2021, 192 cancer survivors (83% curvivors; 17% metavivors) completed optional online surveys of resiliency (CES) and distress (PHQ-8, GAD-7, PSWQ-3) pre- and post- participation in an established clinical program. Mixed effect regression models explored curvivor-metavivor differences at baseline and in pre-post change.

Results

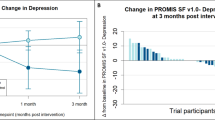

Compared to curvivors, metavivors began the program with significantly more resilient health behaviors (B = 0.99, 95% CI[0.12, 1.86], p = .03) and less depression (B = −2.42, 95%CI[−4.73, −0.12], p = .04), with no other significant differences. Curvivors experienced significantly greater reductions in depression (curvivor-metavivor difference in strength of change = 2.12, 95% CI [0.39, 3.83], p = .02) over the course of the program, with no other significant differences. Neither virtual delivery modality nor proportion of sessions attended significantly moderated strength of resiliency or distress change.

Conclusion

Metavivors entering this mind–body program had relatively higher well-being than did curvivors, and both groups experienced statistically comparable change in all domains other than depression. Resiliency programming may thus benefit a variety of cancer survivors, including those living with incurable cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data analyzed for the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request with ethics board approval.

References

Institute of Medicine, National Research Council (2006) From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition. Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E (eds) The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/11468

Aldaz BE, Treharne GJ, Knight RG, Conner TS, Perez D (2018) ‘It gets into your head as well as your body’: the experiences of patients with cancer during oncology treatment with curative intent. J Health Psychol 23:3–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105316671185

Park ER, Li FP, Liu Y et al (2005) Health insurance coverage in survivors of childhood cancer: the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 23:9187–9197. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.01.7418

Hall DL, Mishel MH, Germino BB (2014) Living with cancer-related uncertainty: associations with fatigue, insomnia, and affect in younger breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 22:2489–2495. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2243-y

Alfano CM, Rowland JH (2006) Recovery issues in cancer survivorship: a new challenge for supportive care. Cancer J 12:432–443. https://doi.org/10.1097/00130404-200609000-00012

Carreira H, Williams R, Müller M et al (2018) Associations between breast cancer survivorship and adverse mental health outcomes: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst 110:1311–1327. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djy177

National Cancer Institute (2022) NOT-CA-22–077: notice of intent to publish a funding opportunity announcement for research to understand and address the survivorship needs of individuals living with advanced cancer (R01 Clinical Trial Optional). https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-CA-22-077.html. Accessed 24 June 2022

Corneliussen-James D (2014) Speaking Out On Metastatic Breast Cancer. METAvivor: Metastatic Breast Cancer Research, Support, and Awareness. https://www.metavivor.org/blog/speaking-out-on-metastatic-breast-cancer. Accessed 19 May 2022

Berlinger N, Gusmano M (2011) Cancer chronicity: new research and policy challenges. J Health Serv Res Policy 16:121–123. https://doi.org/10.1258/jhsrp.2010.010126

Park EM, Rosenstein DL (2014) Living with advanced cancer: unmet survivorship needs. N C Med J 75:279–282. https://doi.org/10.18043/ncm.75.4.279

Harley C, Pini S, Bartlett YK, Velikova G (2015) Defining chronic cancer: patient experiences and self-management needs. BMJ Support Palliat Care 5:343–350. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000200

Park ER, Peppercorn J, El-Jawahri A (2018) Shades of survivorship. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 16:1163–1165. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2018.7071

LeMay K, Wilson KG (2008) Treatment of existential distress in life threatening illness: a review of manualized interventions. Clin Psychol Rev 28:472–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.013

Frick MA, Vachani CC, Bach C et al (2017) Survivorship and the chronic cancer patient: patterns in treatment-related effects, follow-up care, and use of survivorship care plans. Cancer 123:4268–4276. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30862

Antoni MH, Lechner S, Diaz A et al (2009) Cognitive behavioral stress management effects on psychosocial and physiological adaptation in women undergoing treatment for breast cancer. Brain Behav Immun 23:580–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2008.09.005

Carlson LE, Zelinski E, Toivonen K et al (2017) Mind-body therapies in cancer: what is the latest evidence? Curr Oncol Rep 19:67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-017-0626-1

Hall DL, Luberto CM, Philpotts LL et al (2018) Mind-body interventions for fear of cancer recurrence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychooncology 27:2546–2558. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4757

Antoni MH, Moreno PI, Penedo FJ (2023) Stress management interventions to facilitate psychological and physiological adaptation and optimal health outcomes in cancer patients and survivors. Annu Rev Psychol 74:423–455. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-030122-124119

Finkelstein-Fox L, Rasmussen AW, Hall DL et al (2022) Testing psychosocial mediators of a mind-body resiliency intervention for cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 30:5911–5919. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07022-5

Perez GK, Walsh EA, Quain K, Abramson JS, Park ER (2021) A virtual resiliency program for lymphoma survivors: helping survivors cope with post-treatment challenges. Psychol Health 36:1352–1367. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2020.1849699

Hall DL, Park ER, Cheung T, Davis RB, Yeh GY (2020) A pilot mind-body resiliency intervention targeting fear of recurrence among cancer survivors. J Psychosom Res 137:110215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110215

Park ER, Luberto CM, Chad-Friedman E et al (2021) A comprehensive resiliency framework: theoretical model, treatment, and evaluation. Glob Adv Health Med 10:21649561211000304. https://doi.org/10.1177/21649561211000306

Park ER, Traeger L, Vranceanu AM et al (2013) The development of a patient-centered program based on the relaxation response: the Relaxation Response Resiliency Program (3RP). Psychosomatics 54:165–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psym.2012.09.001

Lazarus R, Folkman S (1984) Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. Springer, New York

Hall DL, Yeh GY, O’Cleirigh C et al (2022) A multi-step approach to adapting a mind-body resiliency Intervention for Fear of Cancer Recurrence and Uncertainty in Survivorship (IN FOCUS). Glob Adv Health Med 11:21649561221074690

Gonzalez A, Shim M, Mahaffey B et al (2019) The Relaxation Response Resiliency Program (3RP) in patients with headache and musculoskeletal pain: a retrospective analysis of clinical data. Pain Manag Nurs 20:70–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2018.04.003

Greenberg J, Lin A, Zale EL et al (2019) Development and early feasibility testing of a mind-body physical activity program for patients with heterogeneous chronic pain; the GetActive study. J Pain Res 12:3279–3297. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S222448

Luberto CM, Wang A, Li R et al (2022) Videoconference-delivered mind-body resiliency training in adults with congenital heart disease: a pilot feasibility trial. Int J Cardiol Congenit Heart Dis 7:100324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcchd.2022.100324

Denninger JW, Laubach JP, Yee AJ et al (2017) Psychosocial effects of the relaxation response resiliency program (SMART-3RP) in patients with MGUS and smoldering multiple myeloma: a waitlist controlled randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 35:10051–10051. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.10051

Vranceanu AM, Merker VL, Plotkin SR, Park ER (2014) The relaxation response resiliency program (3RP) in patients with neurofibromatosis 1, neurofibromatosis 2, and schwannomatosis: results from a pilot study. J Neurooncol 120:103–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-014-1522-2

Traeger L, Styklunas GM, Park EY et al (2022) Promoting resilience and flourishing among older adult residents in community living: a feasibility study. Gerontologist 62:1507–1518. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnac031

Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG (1996) The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J Trauma Stress 9:455–471. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490090305

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B (2006) A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 166:1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

Zeynalova N, Schimpf S, Setter C et al (2019) The association between an anxiety disorder and cancer in medical history. J Affect Disord 246:640–642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.019

Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL et al (2009) The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord 114:163–173. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

Gonzalez P, Castañeda SF, Dale J et al (2014) Spiritual well-being and depressive symptoms among cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 22:2393–2400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2207-2

Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL, Borkovec TD (1990) Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behav Res Ther 28:487–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6

Berle D, Starcevic V, Moses K et al (2011) Preliminary validation of an ultra-brief version of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Clin Psychol Psychother 18:339–346. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.724

Wu SM, Schuler TA, Edwards MC, Yang HC, Brothers BM (2013) Factor analytic and item response theory evaluation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire in women with cancer. Qual Life Res 22:1441–1449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-012-0253-0

Hayes AF, Coutts JJ (2020) Use omega rather than Cronbach’s alpha for estimating reliability. But…. Commun Methods Meas 14:1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2020.1718629

Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S (2015) Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw 67:1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01

Rubin DB (1976) Inference and missing data. Biometrika 63:581–592. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/63.3.581

Heron-Speirs HA, Harvey ST, Baken DM (2012) Moderators of psycho-oncology therapy effectiveness: addressing design variable confounds in meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 19:49–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2012.01274.x

Schneider S, Moyer A, Knapp-Oliver S et al (2010) Pre-intervention distress moderates the efficacy of psychosocial treatment for cancer patients: a meta-analysis. J Behav Med 33:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-009-9227-2

Saracino RM, Aytürk E, Cham H et al (2020) Are we accurately evaluating depression in patients with cancer? Psychol Assess 32:98–107. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000765

Greenberg J, Braun TD, Schneider ML et al (2018) Is less more? A randomized comparison of home practice time in a mind-body program. Behav Res Ther 111:52–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2018.10.003

Flanagin A, Frey T, Christiansen SL, AMA Manual of Style Committee (2021) Updated guidance on the reporting of race and ethnicity in medical and science journals. JAMA 326:621–627. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.13304

Acknowledgements

We thank the program participants for their contributions to this research. We also thank April Hirschberg, MD for her work leading clinical groups together with Giselle Perez, PhD, Lara Traeger, PhD, and Elyse Park, PhD, MPH and thank Allyson Foor for assistance with coordination of this clinical program.

Funding

Dr. Finkelstein-Fox’s effort is supported by T32CA092203. Dr. Hall’s effort is supported by K23AT010157. Dr. Perez’s effort is supported by K07CA211955.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Finkelstein-Fox – Conception and design, data collection and assembly, data analysis and interpretation, writing, final approval. Bliss – Conception and design, data collection and assembly, writing, final approval. Rasmussen—Conception and design, data collection and assembly, writing, final approval. Hall—Conception and design, data collection and assembly, writing, final approval. El-Jawahri—Conception and design, writing, final approval. Perez—Conception and design, providing study materials, data collection and assembly, writing, final approval. Traeger—Conception and design, providing study materials, data collection and assembly, writing, final approval. Comander- Conception and design, data collection and assembly, data analysis and interpretation, writing, final approval. Peppercorn- Conception and design, writing, final approval. Anctil- Conception and design, data collection and assembly, writing, final approval. Noonan- Conception and design, writing, final approval. Park- Conception and design, providing study materials, data collection and assembly, data analysis and interpretation, writing, final approval.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Study procedures were approved by the Mass General Brigham IRB (Protocol #2011P001081). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Finkelstein-Fox, L., Bliss, C.C., Rasmussen, A.W. et al. Do cancer curvivors and metavivors have distinct needs for stress management intervention? Retrospective analysis of a mind–body survivorship program. Support Care Cancer 31, 616 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-08062-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-08062-1