Abstract

Purpose

Due to increasing numbers of colorectal and anal cancer survivors, more individuals are living with long-term symptoms after treatment. A systematic review was undertaken to assess the extent to which practice guidelines for colorectal and anal cancer provide recommendations for managing long-term symptoms and functioning impairments.

Methods

Four electronic databases and websites of 30 international cancer societies were searched for clinical practice guidelines, consensus statements, or best practice recommendations for colorectal or anal cancer. Quality of included guidelines was evaluated with the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II tool. Results were narratively summarized.

Results

We included 51 guidelines or consensus statements. Recommendations for managing long-term symptoms or functioning impairments were reported in 13 guidelines (25.4%). All 13 recommend a healthy lifestyle, diet, body weight, and physical activity. The ASCO Colorectal Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline is the most comprehensive, including interventions targeting sexual and bowel function to pain and cognitive issues, and also highlights limited evidence for informing management strategies. Other guidelines recommend treating incontinence, chronic diarrhea, and distress, and stress the need for greater awareness for sexual dysfunction, survivorship clinics, and referrals to specific supportive care interventions.

Conclusions

Few clinical practice guidelines include recommendations for managing long-term symptoms and functioning impairments. It is unclear if this is due to limited evidence or absence of management strategies and interventions. Clear recommendations for managing long-term symptoms and functioning to help health professionals in supporting colorectal and anal cancer survivors are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colon and rectal cancer combined are the third most commonly diagnosed cancer worldwide [1]. In 2018, 1,849,518 new cases of colon or rectal cancer were diagnosed, with an additional 48,541 anal cancers diagnosed [2]. The highest incidence rates are in developed countries, such as Australia with 16,171 newly diagnosed colorectal cancer patients and 470 anal cancer patients in 2018 [3]. Improvements in screening and treatment for bowel, colon, and anal cancer, referred to hereafter as colorectal cancer (CRC), have contributed to a growing population of cancer survivors with unmet needs, long-term symptoms, and functioning impairments after treatment that can negatively impact on health-related quality of life (HRQL) [4, 5].

Multiple long-term symptoms can be experienced after treatment for CRC. For bowel symptoms, these include rectal bleeding, diarrhea, fecal frequency, incontinence and urgency, and rectal tenesmus (feeling of incomplete defecation) [6]. Other common symptoms are chemotherapy-induced neuropathy, insomnia, fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, issues with body image, psychological distress, [7, 8], and sexual dysfunction [5]. All long-term symptoms contribute to increased symptom burden, in terms of both severity and frequency, which in turn is associated with decreased HRQL [9]. In order to decrease symptom burden and improve HRQL, evidence-based interventions should be used to manage long-term symptoms and functioning impairments. Since clinicians are often unaware of interventions designed to detect and manage symptoms [6], this systematic review aimed to investigate the extent to which clinical practice guidelines for CRC provide recommendations for managing long-term symptoms and functioning impairments following treatment for CRC.

Methods

Our systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidance [10]. The following 4 electronic databases were searched using the OVID web gateway: MEDLINE, EMbase, PsycINFO, and CINAHL from inception to 26th of July 2019. The search strategy included terms for colorectal cancer and clinical practice guidelines. Details of the search strategy are reported in Appendix 1. To supplement this, reference lists of studies identified were used to find other relevant guidelines, and 33 international cancer societies and guideline organization websites were searched for additional guidelines, consensus statements, or best practice recommendations.

Eligibility and inclusion criteria

Eligible guidelines were CRC-specific, written in English, and contained information about how to manage or treat long-term symptoms and functioning impairments after treatment. In cases where there was a chronological sequence of versions of a guideline released by a particular organization, only the most recent version of the guideline was reviewed.

Quality assessment

The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation (AGREE) II tool was used to assess the quality of eligible guidelines, i.e., containing information about how to manage or treat long-term symptoms and functioning impairments after treatment [11]. The AGREE II tool consists of 6 domains with 21 quality and two global rating items with 7 point-categories: 1 = did not meet criteria to 7 = met criteria. Quality items relating to guideline rigor, competing interests, and implementation were of particular relevance to our aims as these domains relate to the identification of the best possible evidence to inform the guidelines.

Data extraction and analysis

Data pertaining to country, year of publication, organization, title, and recommendations for management strategies or interventions for long-term symptoms and functioning impairments were extracted. A narrative synthesis of recommendations was conducted.

Results

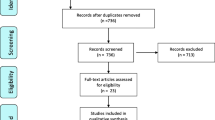

The searches retrieved 545 papers of which 20 were potentially eligible for inclusion. An additional 31 publications were retrieved through searches of international websites (Fig. 1). Fifty-one guidelines for CRC were identified (Appendix Table 3). Major international organizations that published these include the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO), and the European guidelines of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), European Society of Surgical Oncology (ESSO), and European Society of Radiotherapy and Oncology (ESTRO). We found nine guidelines specific to colon cancer, nine for rectal cancer, and five for anal cancer, and twenty-eight guidelines providing recommendations for both colon and rectal cancer.

If information on surveillance was included in the guidelines, it emphasized recurrence detection during follow-up. Only 13 of the 51 guidelines (25.4%) met the eligibility criterion of containing information about how to manage or treat long-term symptoms and functioning impairments after treatment (Table 1).

Quality assessment

The overall quality of the 13 eligible guidelines was high according to the AGREE II criteria (Fig. 2); however, none of the guidelines met all quality criteria. The lowest quality scores related to applicability (e.g., usefulness of guidelines for daily practice), likely barriers/facilitators to implementation, and strategies to improve uptake (Fig. 3).

Quality assessment score (%) according to AGREE II for 13 guidelines that included information on interventions to manage or treat long-term symptoms and functioning impairments after treatment. ESMO, European Society for Medical Oncology; NHMRC, National Health and Medical Research Council; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; GI, gastrointestinal

Information on interventions for long-term symptoms

The American Cancer Society Colorectal Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline is the most extensive, providing detailed information about several issues (Table 2). Long-term symptoms are described and possible interventions outlined. However, the guideline acknowledges that evidence is limited to support treatment, and sometimes management of long-term symptoms/function is based on expert opinion. Moreover, a healthy weight, physical activity, and a multi-fiber diet with low amounts of saturated fat are encouraged [12]. The Alberta Colorectal Cancer Surveillance (stages I, II, and III) guideline refers to the ASCO colorectal cancer survivorship care guideline for information about long-term symptom/functioning management and includes healthy lifestyle promotion recommendations [13].

Four guidelines are published by the NCCN. The survivorship section of the guidelines for rectal cancer, colon cancer, and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) version for colon cancer emphasize the importance of defined roles of care givers in the surveillance period to detect local recurrences in time and state “for chronic diarrhea or incontinence: consider anti-diarrheal agents, bulk-forming agents, diet manipulation, pelvic floor rehabilitation, and protective undergarments” [14,14,15,17]. Moreover, involvement in ostomy support groups or coordination by an ostomy care specialist can be considered, and undergoing national health-screenings, a healthy body weight, physical activity, healthy diet, and not smoking are recommended. Daily aspirin of 325 mg could be considered for secondary prevention. These four guidelines refer readers to NCCN survivorship guidelines for distress, pain, neuropathy, fatigue, sexual dysfunction, or precautions involving physical activity, and to the NCCN guidelines for Distress Management for issues around body changes following treatment for cancer. Further, several guidelines recommend monitoring of long-term symptoms, and functioning impairments should be organized by the primary care physician, who are oncologists in the MENA region [14,14,15,17]. Additionally, in the rectal and anal cancer guidelines, screening for sexual dysfunction and urinary dysfunction is recommended, and referral to a urologist or gynecologist should be made if symptoms persist. Also, bone density monitoring should be considered due to the potential for pelvic fractures after radiotherapy [15, 16]. For oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy, duloxetine is advised or therapies such as heat, ice, or acupuncture [14, 16, 17].

Four CRC guidelines with information on survivorship were published by ESMO. In these guidelines, the use of late effects/survivorship clinics after pelvic radiation is recommended [2, 18,18,20]. For anal cancer, patient-reported outcome data is scarce, but suggests attention to sexual dysfunction is needed. Pelvic floor exercises and biofeedback training are recommended to treat fecal urgency and incontinence [2]. After treatment for rectal cancer, lower genitourinary toxicity and social, financial, and emotional aspects should be addressed to maximize well-being, but recommendations for how to address these issues are not provided [18]. Only the guideline for early colon cancer describes how to treat cancer sequelae and highlights that assessment of medical and psychological late effects are a major part of survivorship care. Dietary counseling and use of over-the-counter medications such as fiber, laxative, stool softeners, and antidiarrheals are recommended. Employment, financial concerns, and distress should also be assessed [19]. Further, all four guidelines emphasize a healthy lifestyle to prevent co-morbidity [2, 18,18,20].

The Cancer Care Ontario Follow-up care guideline for survivors of colorectal cancer states that despite a lack of high-quality evidence for secondary prevention, patients should be counseled to have a healthy lifestyle, body weight and diet, and to participate in physical activity [21]. This is also recommended in the German guideline with the addition that “patients benefit if they can take the management of their symptoms and side effects into their own hands” [22]. However, recommendations for how to self-manage symptoms are not provided. A separate section on psychological care and treatments is included in the Australian guideline of the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). It recommends routine screening with the Distress Thermometer and the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Schedule and provides a range of evidence-based psychological interventions if required. These include relaxation-based, cognitive behavioral, and supportive-expressive therapies. Early referral to a psychologist or liaison psychiatrist is advised, and also peer support was accepted and appreciated by CRC survivors. [23]

Discussion

Of the 51 CRC-specific guidelines identified, only 13 (25%) contained recommendations for how to manage some long-term symptoms and functioning impairments following treatment for CRC. These 13 guidelines were published by the NCCN, ESMO, ASCO, Cancer Care Ontario, Alberta provincial GI tumor team, German Guideline program in oncology, and the NHMRC. All 13 guidelines recommend a healthy lifestyle, diet and body weight, and physical activity. The ASCO guideline provides the most comprehensive coverage of interventions ranging from cognitive and pain to bowel and sexual issues, and also acknowledges that evidence is limited to support base treatment guidelines. Other guidelines include some suggestions for treating chronic diarrhea, incontinence and psychological distress, and highlight need for greater awareness for sexual dysfunction, survivorship clinics, and referrals to specific supportive care interventions. Thus, few clinical practice guidelines for CRC provide a comprehensive range of recommendations for how to manage or treat long-term symptoms and functioning impairments following treatment for CRC.

The main focus of survivorship care in the guidelines is on detection of early recurrence, the timing of follow-up, and which diagnostic tools to use. Much less attention is paid to long-term symptoms and functioning impairment, or to the interventions recommended to manage and alleviate these issues to reduce patients’ symptom burden and improve HRQL. This is a major gap that needs to be filled as previous research demonstrates a link between HRQL and survival. In a large study of 1074 CRC patients, depressive symptoms significantly increased mortality risk in the first 2 years after diagnosis (hazard rate, 2.55, p = 0.001) with a hazard rate of 1.88 (p < 0.01) up to 10 years after diagnosis [24]. During the last few decades, more attention is being paid to developing interventions for late symptoms after cancer treatment. For example, Andreyev et al. reported that a gastroenterologist- or nurse-led algorithm-based treatment resulted in a decrease of bowel symptoms compared with a self-help booklet [25]. Also, interventions are emerging for sexual dysfunction after pelvic radiotherapy, such as mindfulness and cognitive behavioral therapy, couple therapy, scheduled intimacy, vaginal dilator therapy and moisturizers, hormone replacement, and phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors [26]. Research is needed to further assess interventions for long-term symptoms and functioning impairments. Moreover, guidelines recommend screening for distress and symptoms, but do not state if patient-reported outcomes could or should be used for routine screening. A number of trials have shown benefit of using patient-reported outcomes for routinely screening during treatment [27, 28]; their potential benefit in long-term follow-up of CRC should be investigated.

Several guidelines refer to generic survivorship guidelines. While these were excluded from our review, we note that the 2019 NCCN survivorship guideline contains information about long-term symptoms and treatment of cardiotoxicity, depression, anxiety, cognitive function, fatigue, lymphoedema, hormone problems, pain, sexual function, and sleep, independent of the location of the primary cancer. Unfortunately, interventions for gastrointestinal problems are not included [29]. NCCN regularly updates all guidelines. The NCCN guidelines for colon and rectal cancer met our inclusion criteria regarding information on long-term adverse effects after treatment and possible interventions, but in an older version (the NCCN CRC guideline), such information was not provided. The inclusion of this information in the updated guideline suggests rising international awareness for late effects and HRQL.

This systematic review highlights the limited guidance available on how to manage long-term symptoms and functioning impairments in CRC survivors. This knowledge gap has implications for both clinicians, patients, and their informal caregivers. A previous review showed that many CRC survivors find ways to self-manage their symptoms through trial and error rather than seek professional help [30]. Self-help strategies are often not evidence-based, so it may not be effective and perhaps even detrimental, worsening symptoms or impairment. It is not clear why survivors choose to self-manage, but the absence of recommendations for clinicians in clinical practice guidelines may at least in part be a contributing factor. Moreover, none of the guidelines addressed the need to support informal caregivers in managing symptoms. As mentioned above, interventions have been developed to manage several symptoms and functions caused by treatment for cancer, yet expert opinions are often used to inform clinical practice guidelines rather than evidence from clinical effectiveness trials. It is unclear whether the use of expert opinion is due to limited effectiveness evidence. Future research should focus on synthesizing all available evidence on supportive care interventions and management strategies, and guidelines need to be updated periodically to incorporate emerging evidence. Another recommendation, also stated in a few guidelines, is the use of survivorship clinics. Literature shows that patients are highly satisfied with the services of such a clinic, mainly due to the multidisciplinary approach, the time taken to address the symptoms, and the referrals to appropriate supporting programs [31].

Strengths of this review are the inclusion of international guidelines, a thorough search of both electronic databases and websites for 33 cancer societies, and guideline quality assessment against the criteria of the AGREE II tool. Two limitations of our review were the inclusion of only guidelines available in English, and with our search process, we could not accurately count the number of non-English guidelines excluded. Some non-English guidelines that we did not have resources to review may provide recommendations for long-term symptoms or functions. For example, the Dutch national guideline for CRC (which we are aware of as LW is a Dutch clinician) provides risk factors for fecal incontinence, recommends the use of diagnostic tools to evaluate long-term symptoms, and provides interventions for managing specific problems such as fecal incontinence with bulk-forming agents or loperamide to decrease fecal frequency [32]. However, despite excluding non-English guidelines, we expect that they would be informed by the same international evidence that informed guidelines published in English.

In conclusion, the majority of guidelines for CRC reviewed did not provide recommendations for management of long-term symptoms and functioning impairment following treatment for CRC. Their recommendations primarily focus on detection of early recurrence, the timing of follow-up, which diagnostic tools to use, and on the importance of a healthy diet and weight, and active lifestyle after treatment. Few recommendations are available for how to reduce or manage symptom burden and improve HRQL. This may be due to lack of evidence about effectiveness of potential management strategies. There is need for clear evidence-based recommendations for managing long-term symptoms and functioning impairments to assist health professionals in supporting CRC survivors and to ameliorate suffering due to persistent symptoms and functioning impairments that often go unmanaged.

References

Ferlay J et al (2012) Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN. Int J Cancer 136(5):E359–E386

Glynne-Jones R et al (2014) Anal cancer: ESMO-ESSO-ESTRO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 25(Supplement.3):iii10–iii20

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer compendium: information and trends by cancer type 2019 September 30, 2019]; Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer/cancer-data-in-australia/contents/summary

Glaser AW et al (2013) Patient-reported outcomes of cancer survivors in England 1–5 years after diagnosis: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 3(4)

Wiltink LM, Chen TY, Nout RA, Kranenbarg EM, Fiocco M, Laurberg S, van de Velde C, Marijnen CA (2014) Health-related quality of life 14 years after preoperative short-term radiotherapy and total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: report of a multicenter randomised trial. Eur J Cancer 50(14):2390–2398

Andreyev HJ, Davidson SE, Gillespie C, Allum WH, Swarbrick E, British Society of Gastroenterology, Association of Colo-Proctology of Great Britain and Ireland, Association of Upper Gastrointestinal Surgeons, Faculty of Clinical Oncology Section of the Royal College of Radiologists (2012) Practice guidance on the management of acute and chronic gastrointestinal problems arising as a result of treatment for cancer. Gut 61(2):179–192

Jansen L et al Health-related quality of life during the 10 years after diagnosis of colorectal cancer: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol 29(24):3263–3269

Mols F et al Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy and its association with quality of life among 2- to 11-year colorectal cancer survivors: results from the population-based PROFILES registry. J Clin Oncol 31(21):2699–2707

Deshields TL, Potter P, Olsen S, Liu J (2014) The persistence of symptom burden: symptom experience and quality of life of cancer patients across one year. Support Care Cancer 22(4):1089–1096

Moher D et al (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine 6(7)

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L, AGREE Next Steps Consortium (2010) AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting, and evaluation in health care. Prev Med 51(5):421–424

El-Shami K et al (2015) American Cancer Society colorectal Cancer survivorship care guidelines. CA Cancer J Clin 65:427–455

Alberta Provincial GI Tumour Team , Colorectal cancer surveillance (stages I, II, and III) 2019 August 27, 2019]; Available from: https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/hp/cancer/if-hp-cancer-guide-gi002-colon-surveillance.pdf

National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Colon cancer MENA v 4.2018. 2018 August 27, 2019]; Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/colon-mena.pdf

National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Anal carcinoma, Version 1.2019. 2019 August 27, 2019]; Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/anal.pdf

National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Rectal cancer, version 2.2019. 2019 August 27, 2019]; Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/rectal.pdf

National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Colon cancer, version 2.2019. 2019 August 27, 2019]; Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colon.pdf

Glynne-Jones R et al (2017) Rectal cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 28(suppl_4):iv22–iv40

Labianca R et al (2013) Early colon cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 24(SUPPL.6):vi64–vi72

Schmoll HJ, Van Cutsem E, Stein A, Valentini V, Glimelius B, Haustermans K, Nordlinger B, van de Velde CJ, Balmana J, Regula J, Nagtegaal ID, Beets - Tan RG, Arnold D, Ciardiello F, Hoff P, Kerr D, Köhne CH, Labianca R, Price T, Scheithauer W, Sobrero A, Tabernero J, Aderka D, Barroso S, Bodoky G, Douillard JY, El Ghazaly H, Gallardo J, Garin A, Glynne - Jones R, Jordan K, Meshcheryakov A, Papamichail D, Pfeiffer P, Souglakos I, Turhal S, Cervantes A (2012) ESMO consensus guidelines for management of patients with colon and rectal cancer. A Personalized Approach to Clinical Decision Makin. Ann Oncol 23:2479–2516

Earle C, et al. Follow-up care, surveillance protocol, and secondary prevention measures for survivors of colorectal cancer 2012 July 30, 2019]; Available from: https://www.cancercareontario.ca/en/content/follow-care-surveillance-protocols-and-secondary-prevention-measures-survivors-colorectal-cancer

German Guideline Program in Oncology, Evidenced-based guideline for colorectal cancer version 2.1. 2019 August 27, 2019]; Available from: https://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Downloads/Leitlinien/Kolorektales_Karzinom/Version_2/GGPO_Guideline_Colorectal_Cancer_2.1.pdf

Brown JC, Schmitz KH (2014) The prescription or proscription of exercise in colorectal cancer care. Med Sci Sports Exerc 46(12):2202–2209

Mols F, Husson O, Roukema JA, van de Poll-Franse L (2013) Depressive symptoms are a risk factor for all-cause mortality: results from a prospective population-based study among 3,080 cancer survivors from the PROFILES registry. J Cancer Surviv 7(3):484–492

Andreyev HJ, Benton BE, Lalji A, Norton C, Mohammed K, Gage H, Pennert K, Lindsay JO (2013) Algorithm-based management of patients with gastrointestinal symptoms in patients after pelvic radiation treatment (ORBIT): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 382(9910):2084–2092

White ID (2015) Sexual difficulties after pelvic radiotherapy: improving clinical management. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 27(11):647–655

Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, Scher HI, Hudis CA, Sabbatini P, Rogak L, Bennett AV, Dueck AC, Atkinson TM, Chou JF, Dulko D, Sit L, Barz A, Novotny P, Fruscione M, Sloan JA, Schrag D (2016) Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 34(6):557–565

Velikova G, Booth L, Smith AB, Brown PM, Lynch P, Brown JM, Selby PJ (2004) Measuring quality of life in routine oncology practice improves communication and patient well-being: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 22(4):714–724

National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Survivorship, version 2.2019. 2019 August 27, 2019]; Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/survivorship.pdf

Rutherford C, et al. (under review) Patient reported outcomes and experiences from the perspective of colorectal cancer survivors: meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. J Patient Reported Outcome

Tan SY, Turner J, Kerin-Ayres K, Butler S, Deguchi C, Khatri S, Mo C, Warby A, Cunningham I, Malalasekera A, Dhillon HM, Vardy JL (2019) Health concerns of cancer survivors after primary anti-cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer 27(10):3739–3747

Integraal Kankercentrum Nederland (IKNL), Colorectaal carcinoom. 2014 August 27, 2019]; Available from: https://www.oncoline.nl/colorectaalcarcinoom

Funding

This project was supported by the generous contributions of the Estate of the Late Emma Elwin (Ellie) a’Beckett Fellowship Grant awarded to Claudia Rutherford.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Data control

All primary data of this systematic review consists of guidelines published as papers of international journals or on website of scientific communities. Since these are public guidelines the journal could review these.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Systematic search strategy

Topic (colorectal cancer)

-

1.

(colorectal adj1 (cancer* or neoplasm* or tumo$r$ or carcinoma$)).ti,ab,mp

-

2.

(bowel adj1 (cancer$ or neoplasm$* or tumo$r$ or carcinoma$)).ti,ab,mp

-

3.

(colon adj1 (cancer$ or neoplasm$ or tumo$r$ or carcinoma$)).ti,ab,mp

-

4.

(anal adj1 (cancer$ or neoplasm$ or tumo$r$ or carcinoma$)).ti,ab,mp

-

5.

((rectal or rectum or anal) adj1 (cancer$ or neoplasm$ or tumo$r$ or carcinoma$)).ti,ab,mp

-

6.

or/1-6

Outcomes

-

7.

(clinical practice guideline*).ti,ab,kw

-

8.

(clinical guideline*).ti,ab

-

9.

(best practice guideline*).ti,ab

-

10.

((survivorship or supportive care) guideline*).ti,ab,kw

-

11.

(treatment recommendation*).ti,ab

-

12.

(evidence$based recommendation*).ti,ab

-

13.

(clinical pathway).ti,ab

-

14.

(care pathway*).ti,ab,kw.

-

15.

or/7-14

Exclusion

-

16.

Prevention

-

17.

(p$ediatric* or child* or infant* or youth* or adolescen*).ti,ab.

-

18.

animal*.mp,ti,ab.

-

19.

(mouse or rat or mice).ab.

-

20.

(in vivo or in vitro).mp.

-

21.

((semi-structur* or semistructur* or unstructur* or informal or in-depth or indepth or face-to-face or structur* or guide) adj3 (interview* or discussion* or questionnaire*)).ti,ab.

-

22.

interviews as topic/

-

23.

(focus group* or qualitative or ethnograph* or fieldwork or “field work” or “key informant”).ti,ab.

-

24.

focus groups/ or narration/ or qualitative research/

-

25.

(retraction of publication or retracted publication).pt.

-

26.

(cohort analysis or cohort study).pt,ab,ti,kw.

-

27.

longitudinal stud*.pt,ab,ti,kw.

-

28.

retrospective.ti,ab.

-

29.

Epidemiolog*.ti,ab.

-

30.

cross-section*.ti,ab.

-

31.

Case Control Study/ or Control Group/

-

32.

(case$ and control$).mp,tw.

-

33.

(case$ and series).tw.

-

34.

Matched-Pair Analysis/

-

35.

(animal* not human*).sh.

-

36.

historical article.pt.

-

37.

review.pt.

-

38.

letter.pt.

-

39.

comment.pt.

-

40.

editorial.pt.

-

41.

or/16-40

-

42.

6 and 15

-

43.

42 not 41

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wiltink, L.M., White, K., King, M.T. et al. Systematic review of clinical practice guidelines for colorectal and anal cancer: the extent of recommendations for managing long-term symptoms and functional impairments. Support Care Cancer 28, 2523–2532 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05301-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05301-7