Abstract

Two mutually unexclusive hypotheses prevail in the theory of nutritional ecology: the balanced diet hypothesis states that consumers feed on different food items because they have complementary nutrient and energy compositions. The toxin-dilution hypothesis poses that consumers feed on different food items to dilute the toxins present in each. Both predict that consumers should not feed on low-quality food when ample high-quality food forming a complete diet is present. We investigated the diet choice of Phytoseiulus persimilis, a predatory mite of web-producing spider mites. It can develop and reproduce on single prey species, for example the spider mite Tetranychus urticae. A closely related prey, T. evansi, is of notorious bad quality for P. persimilis and other predator species. We show that juvenile predators feeding on this prey have low survival and do not develop into adults. Adults stop reproducing and have increased mortality when feeding on it. Feeding on a mixed diet of the two prey decreases predator performance, but short-term effects of feeding on the low-quality prey can be partially reversed by subsequently feeding on the high-quality prey. Yet, predators consume low-quality prey in the presence of high-quality prey, which is in disagreement with both hypotheses. We suggest that it is perhaps not the instantaneous reproduction on single prey or mixtures of prey that matters for the fitness of predators, but that it is the overall reproduction by a female and her offspring on an ephemeral prey patch, which may be increased by including inferior prey in their diet.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Many predators face the task of selecting their diet from among various prey types and species, and, according to the balanced diet hypothesis, feed on a mixed diet to acquire energy and nutrients needed for growth and development (Pulliam 1975; Bilde and Toft 1994; Raubenheimer and Simpson 1997; Mayntz et al. 2005; Lefcheck et al. 2013). They also need to avoid adverse effects of feeding on toxic prey, which they can do by mixing them with non-toxic prey (the so-called toxin-dilution hypothesis, Freeland and Janzen 1974; Toft and Wise 1999a; Lefcheck et al. 2013). Toft and Wise (1999a) define high-quality prey as those that sustain development and reproduction and result in low mortality. Low-quality prey are then those that fall short in allowing for development, survival and/or reproduction, and this may be because of lack of essential nutrients or because of toxicity. Feeding on such low-quality prey is not expected under natural conditions unless it confers some benefit to the predators (Toft 1995), for example, because they provide nutrients or energy that would be in short supply when feeding on high-quality prey only. This includes feeding on a limited number of low-quality prey to avoid starvation when other prey are scarce (Rickers et al. 2006; Glendinning 2007). Thus, scarcity of high-quality prey could result in selection for adaptation to low-quality prey or other food, hence, towards more generalist feeding habits. Otherwise, adding low-quality food to a high-quality diet usually decreases predator performance (Eubanks and Denno 1999; Toft and Wise 1999a, b; Bilde and Toft 2001; Oelbermann and Scheu 2002; Lefcheck et al. 2013), and is therefore not expected. If toxic prey do not provide scarce nutrients and predators do not innately have an aversion to them, predators can deal with their occurrence in the environment either by learning to avoid them (Fisker and Toft 2004; Glendinning 2007; Nelson et al. 2011) or by becoming tolerant to the toxins (Freeland and Janzen 1974; Glendinning 2007). In contrast to these theoretical expectations, here we present evidence that a predator feeds on a prey species of low quality, even when its high-quality prey is abundant and there is no advantage of feeding on a mixed diet.

We used the well-studied predatory mite species Phytoseiulus persimilis, a biological control agent of the two-spotted spider mite (Tetranychus urticae) in many agricultural systems (van Lenteren 2012). This spider mite is used here as benchmark high-quality prey. The predator can develop and reproduce perfectly well during multiple generations on a diet of T. urticae alone (Stenseth 1979), hence, apparently does not need a mixed diet. Phytoseiulus persimilis does not perform well on Tetranychus evansi, which is a low-quality prey for several predators (de Moraes and McMurtry 1985, 1986; Escudero and Ferragut 2005; Koller et al. 2007; de Vasconcelos et al. 2008). Thus far, only one predatory mite species, Phytoseiulus longipes, has been reported to perform well on it (Furtado et al. 2007; da Silva et al. 2010; Ferrero et al. 2014). Although the two spider mite species are closely related, there are more differences between them than their quality as prey. Tetranychus urticae is extremely polyphagous, attacking more than 1150 plant species worldwide (Migeon and Dorkeld 2020). Tetranychus evansi is more specialized, occurring on c. 130 plant species, especially solanaceous plants (Migeon and Dorkeld 2020). It has been suggested that T. evansi is a low-quality prey because it accumulates or sequesters the toxic secondary plant compounds amply present in their solanaceous host plants (Kennedy 2003; Escudero and Ferragut 2005; Koller et al. 2007; Ferrero et al. 2014). Another difference between the two species is that many strains of T. urticae induce defences in their host plants, whereas T. evansi suppresses them in several plant species (Kant et al. 2004; Sarmento et al. 2011a; Alba et al. 2015; de Oliveira et al. 2016; Knegt et al. 2020). Lastly, T. urticae is found almost everywhere (Migeon and Dorkeld 2020), but T. evansi originates from South America and has only recently invaded Africa, Europe and Japan (Navajas et al. 2013), In Europe, it now co-occurs with T. urticae and P. persimilis (Escudero and Ferragut 2005). Several of these differences in ecology of the two spider mite species have been implicated as being related to their quality as prey. Here, however, we do not investigate the cause of the low quality of T. evansi as prey, but concentrate on its consequences for the diet choice and performance of P. persimilis.

We first assessed the effects of feeding on low-quality prey and on a mixture of low-quality and high-quality prey on predator survival and development. We also evaluated prey preference and reproduction on the two prey and investigated whether experience with the low-quality prey resulted in the development of aversion towards this prey. Furthermore, we investigated the reversibility of the negative effects of feeding on the low-quality prey on development and reproduction.

Material and methods

Organisms

Tomato seeds (Solanum lycopersicum var. Santa Clara I-5300) were sown in soil (50% coco peat, 15% white peat, 35% frozen black peat, Jongkind Grond BV, Aalsmeer) in a PVC tray (6 × 12 cells) and plants were transplanted to plastic pots (2 L) with soil 14 days after germination. The rearing units of T. evansi and T. urticae at the University of Amsterdam were started with specimens from the Laboratory of Acarology, Federal University of Viçosa, Minas Gerais, Brazil, collected in 2002 from infested tomato plants (Sarmento et al. 2011a, b). They were reared on detached tomato leaves kept in plastic trays (30 × 22 cm, 8 cm high) containing water to maintain leaf turgor. These trays were placed inside larger trays (54 × 38 cm, 8.5 cm high) filled with water with detergent (c. 1:50, v/v) to prevent escapes of mites and contamination among populations. The rearing units were maintained in a climate room (25 °C, 70 – 80% relative humidity, 16 h light).

Phytoseiulus persimilis was obtained from Koppert (Berkel and Rodenrijs, the Netherlands) and was kept on detached cucumber leaves infested with T. urticae, to which it was adapted. From this stock rearing unit, we started a new unit 1 month before the experiments, which was fed with the Brazilian strain of T. urticae. This unit was kept in a plastic tray (30 × 22 cm, 8 cm high) inside a larger PVC tray (54 × 38 cm, 8.5 cm high) filled with water with detergent (as above). Two to three tomato leaves infested with spider mites were added to the inner tray every three to four days. The units were maintained in a climate room (as above).

The predators used in our experiments came from cohorts obtained by taking approximately 30 adult females of P. persimilis from the new rearing unit and transferring them to tomato leaflets infested with T. urticae arranged on wet cotton wool in plastic trays. The females were allowed to feed and oviposit for 24 h, were then removed, and the leaflets with predator eggs and prey were either incubated in a climate room (as above), or predator eggs were used immediately for the experiments. Adult female P. persimilis go through a pre-oviposition period of around 1.5 days, during which they increase about 60% in weight and reach a body length of c. 0.6 mm (Sabelis 1981). After 7–9 days, the cohort of predatory mites was adult; the females were allowed to mate and were subsequently used for experiments.

Juvenile performance

We measured the performance of juvenile predatory mites feeding on eggs of T. urticae and T. evansi. Predators without food were used as control. The predators develop from eggs to a six-legged larva stage, the only mobile stage that does not require food, to the eight-legged protonymph (Takafuji and Chant 1976; Sabelis 1981). Protonymphs start feeding on spider mite eggs and juveniles and develop into deutonymphs, which develop into adults.

Leaf discs (diameter 24 mm) were cut from leaves of clean tomato plants and arranged on paper tissue soaked with water, positioned on wet foam inside a tray (12.5 by 7.5 cm, 2.5 cm high) filled with tap water. The wet tissue prevented the mites from escaping from the discs. Each leaf disc was infested with 20 adult females of T. evansi or T. urticae, taken from stock rearing units. The trays with the leaf discs were incubated in a climate room (as above) for 24 h. Subsequently, spider mite females and the web produced by them were removed from leaf discs using a fine paintbrush, leaving their eggs behind. The numbers of eggs of spider mites on each leaf disc were recorded.

One egg from a cohort of P. persimilis was transferred to each leaf disc. For logistical reasons, this experiment was performed in three blocks that were repeated in time. As the stock populations of the two spider mites fluctuated differentially through time, the number of replicates varied according to the availability of spider mites and ranged from 18 (T. urticae and no food, with 6 replicates in each of three blocks) to 24 (T. evansi with 6, 12 and 6 replicates in the three blocks). We observed the development, survival and predation rate of juveniles of P. persimilis from egg to adult once a day. The various stages were assessed by checking for exuviae resulting from moulting. Because spider mite eggs take around four days to hatch at 25 °C (Bonato 1999), the leaf discs were replaced with new leaf discs with spider mite eggs of the corresponding treatments every three or four days. At removal, ample numbers of prey eggs were still present. Leaf discs without spider mite eggs (treatment No food) were also replaced.

Survival data were analyzed with a Cox mixed-effects proportional hazards model (package coxme, Therneau 2015) with block as a random factor and food type as factor. Pairwise comparisons among diets were done with the function emmeans from the package with the same name (Lenth 2019). Because the treatment without food did not result in development into adults for obvious reasons, development data were analyzed with the Kaplan–Meier estimates (packages survdif and survminer, Therneau 2020; Kassambara et al. 2020) with prey type as a factor. The average predation rate per day was calculated per juvenile and was log(x + 1) transformed and compared for the two prey species with a linear mixed-effects model (LME, function lme of the package nlme, Pinheiro et al. 2020) with prey as a factor and block as a random factor. All statistics were calculated with R statistical software (R Core Team 2020).

Prey preference and adult performance on mixed and single diets

After a pre-oviposition period, female P. persimilis convert spider mites into predator eggs with an efficiency of c. 70% on a weight basis (Sabelis 1981), hence, reproduction is strongly affected by prey consumption. We, therefore, assessed both oviposition and prey consumption by adult female predators. Tomato leaf discs (as above) were cut from detached leaves so that the main leaf vein divided the discs into two halves with approximately similar areas. Each disc half was infested with 20 adult females of either T. evansi or T. urticae from the stock rearing units. To prevent spider mites from crossing from one half to the other, a thin thread of wet cotton wool was put along de midrib, contacting the surrounding water so that it was soaked (Pallini et al. 1998). The trays with the leaf discs were incubated in a climate room (conditions as above) for 24 h, adult female spider mites and web were subsequently removed and eggs were counted. The cotton thread was removed from the leaf midrib and an entomological pin was inserted at the centre of the disc, drilling the midrib (Dicke and Dijkman 1992). An adult female P. persimilis (8–10 days since egg stage) was carefully placed on the tip of the entomological pin. The predators immediately moved down to the leaf disc and started attacking eggs. Similar leaf discs were prepared for each prey species separately as controls, except that we transferred 20 adult females of the same prey species (40 adult females per disc in total) to both halves of the leaf discs, removed them and their web 24 h later and counted the eggs as above. The numbers of eggs (± s.e.) of both prey species encountered in the mixed prey species treatment and controls were 122.08 (± 2.39) for T. urticae and 111.81 (± 3.36) for T. evansi. The experiment was done in two blocks in time, with each block having replicates of all treatments. There were 12 replicates of each treatment with 3 replicates of each in the first block and 9 of each in the second block.

The survival, predation and oviposition rates of P. persimilis were observed during four consecutive days, after which ample numbers of spider mite eggs were still present. Data of individuals that died or went missing were included in the analysis of predation and oviposition data until the day they were absent. The predation data of predators that received a mixed diet served to analyse prey preference by comparing the numbers of each of the two prey species eaten with an LME with prey species and its interaction with time as fixed factors and each individual predatory mite as a random factor to account for repeated measures. The blocks in which the experiment was performed were initially entered as a second random factor, but proved not significant, so were removed. Contrasts were assessed with the package emmeans (Lenth 2019). Survival of adult predators during the experiment was analyzed with Kaplan–Meier estimates (Kassambara et al. 2020; packages survdif and survminer, Therneau 2020) with the diet as a factor. To assess whether there was an effect of the numbers of T. evansi consumed on predator survival, we analyzed the survival of individuals feeding on a mixed diet or a diet of T. evansi with a GLM with a binomial error distribution (logit link) with the average daily intake of T. evansi eggs as factor.

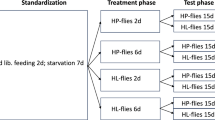

Reversibility of diet effects

Because the previous experiments showed negative effects of feeding on T. evansi eggs on juvenile and adult performance, we investigated whether these effects were reversible, in which case the negative effects of temporarily feeding on low-quality prey may be limited. For juveniles, leaf discs were prepared as above, and larvae of P. persimilis (one day old) were each transferred to a leaf disc, containing either eggs of T. evansi, eggs of T. urticae or no food. Survival and development of the juvenile predators were assessed during two consecutive days. After these two days, the effects of the different diets were apparent, and we transferred the juveniles to new leaf discs with eggs of T. urticae, prepared as above, to study the reversibility of the diet effects. Subsequently, the development and survival of the juveniles of P. persimilis were evaluated daily until they reached adulthood or died. We registered the numbers of eggs killed by the juvenile predators throughout the experiment. There were 12 individuals for each treatment. Survival and development until adulthood were analyzed with a Cox proportional hazards model as above.

For adult performance, leaf discs were cut from tomato leaves and arranged in plastic trays as described above, and 20 adult female spider mites (T. urticae or T. evansi) from the stock colonies were used to infest leaf discs separately. Further preparation of the discs was as above. All adult female predatory mites (age as above) were offered leaf discs with eggs of T. urticae for the first two days to verify that they oviposited. Subsequently, they were transferred to new leaf discs with either eggs of T. evansi, eggs of T. urticae or no food and were kept on these leaf discs for two consecutive days, after which they were transferred to new leaf discs with eggs of T. urticae. Survival, the numbers of eggs they produced, and the numbers of prey eggs killed were assessed daily. Survival data of females that were alive for at least three days were analyzed with a Cox proportional hazards model in R (Therneau 2020). This resulted in 19, 21 and 23 individuals for the treatments with T. evansi, without food and with T. urticae, respectively. Oviposition of predators that did not survive until the fourth day of the experiment was excluded from the analysis, resulting in 10, 11 and 18 individuals for the treatments with T. evansi, without food, and with T. urticae, respectively. The remaining data were analyzed with a linear mixed-effects model (Pinheiro et al. 2020) with individuals as a random factor and treatment and day as factors. To check whether the predators receiving the three treatments did not differ from each other before treatments, we first analyzed the data of the first two days for all three groups together. Subsequently, oviposition data of the third and the fourth day were analyzed for the two groups that received prey, and for all three groups for the last two days.

Results

Juvenile performance

Immature survival varied significantly with diet (Fig. 1a, Cox mixed-effects model: Chi2 = 27.5, d.f. = 2, P < 0.0001). Immature P. persimilis survived significantly better on a diet of eggs of T. urticae than on eggs of T. evansi and without food. Diet also significantly affected the cumulative proportions of juveniles that developed into adults through time (Fig. 1b, Mantel–Heanszel test of Kaplan–Meier survival estimates: Chi2 = 32.3, d.f. = 2, P < 0.0001). As expected, juveniles did not develop into adults without prey. Most juveniles became adults when feeding on eggs of T. urticae, and only one juvenile became adult on a diet of T. evansi (Fig. 1b). The developmental rate was significantly higher on a diet of T. urticae than on the other diets (Fig. 1b). Larvae raised without food that did not go missing during the experiment developed into the next stage (protonymphs) (Fig. 1c). On a diet of T. evansi, most individuals died as protonymphs, a few developed into deutonymphs, one developed into an adult and one died as egg (Fig. 1c). On a diet of T. urticae, most individuals developed into adults, but one died as egg and one as protonymph (Fig. 1c).

The performance of juvenile Phytoseiulus persimilis on diets consisting of eggs of T. urticae or T. evansi on leaf discs of bean, cucumber or tomato. a. The cumulative proportion (± s.e.) of juveniles surviving from the egg stage to adulthood per prey species as a function of individual age. Letters next to the legend give significance among diets. b. The cumulative proportions (± s.e.) of juveniles that became adult as a function of age of the individuals. Letters next to the legend give significance among diets. c. The final stages reached by the juveniles as function of their diet, shown as a proportion of the initial numbers of individuals

All protonymps and deutonymphs consumed eggs of the species present, but juveniles on a diet of T. evansi consumed on average 4.5 (s.e. ± 0.5) eggs and those on a diet of T. urticae only 2.4 (± 0.2) eggs, and this difference was significant (LME: likelihood ratio = 11.9, d.f. = 1, P = 0.0006). This shows that the lack of development on a diet of eggs of T. evansi was not caused by lack of finding prey eggs.

Prey preference and adult performance on mixed and single diets

All adult predators receiving a mixed diet consumed T. evansi eggs, but they consumed significantly more eggs of T. urticae than of T. evansi (Fig. 2a mixed treatment, LME: likelihood ratio = 85.4, d.f. = 1, P < 0.001). This preference did not change significantly throughout the experiment (interaction of prey species with time, likelihood ratio 2.59, d.f. = 1, P = 0.107), showing that the predators did not learn to avoid feeding on T. evansi.

Performance of adult female P. persimilis on diets of eggs of T. urticae, T. evansi or on a mixture of the two. a. Average predation (± s.e.) of eggs of the two species during 4 days by predators feeding on a mixed diet. b. The cumulative proportion of adults (± s.e.) surviving during the four days of the experiment. Letters next to the curves give significance among diets. c. Incidence of mortality as a function of the average number of T. evansi eggs consumed per day. The curve is fitted with a GLM with a binomial error distribution. d. Average oviposition (± s.e.) by females feeding on these diets during 4 days. Vertical text along horizontal axis gives diet. Different letters above bars give significance of difference among diets per day, white capital letters within bars give significance of difference among days per diet (contrasts after LME, P < 0.05)

The survival of adult predators differed significantly among diets (Mantel–Heanszel test of Kaplan–Meier survival estimates: Chi2 = 16.1, d.f. = 2, P = 0.0003), with a diet of T. evansi alone resulting in significantly lower survival than the other two diets (Fig. 2b). For those predators that fed on eggs of T. evansi (diet T. evansi and mixed diet), mortality increased significantly with the numbers of T. evansi eggs consumed (Fig. 2c, GLM: Chi2 = 16.9, d.f. = 1, P = 0.001).

Predators on a diet of T. evansi alone produced significantly fewer eggs than predators with the two other diets throughout the experiment; their oviposition on the first day was mainly based on the food ingested on the day before (Sabelis 1990) and they stopped ovipositing after the first day (Fig. 2d). Predators on a mixed diet produced similar numbers of eggs as predators on a diet of T. urticae during the first two days, but subsequently produced significantly fewer eggs. Together, this resulted in a significant effect of the interaction of diet with time (LME: likelihood ratio = 15.9, d.f. = 2, P = 0.0004). The differences in oviposition rates among diets were largely a reflection of the differences in predation rates (Supplementary Material S1).

Together, these results show that eggs of T. evansi are indeed of low quality for adult predators, causing increased mortality and decreased oviposition. The predators preferred the high-quality prey, but they did not show signs of completely avoiding feeding on low-quality prey in the presence of high-quality prey.

Reversibility of diet effects

Because the previous experiments showed a negative effect of consuming T. evansi eggs on the performance of P. persimilis, we investigated whether these effects were temporary or permanent. The juvenile survival of predators that were reared on different diets during the first two days since larva and then on eggs of T. urticae did not differ significantly among groups receiving different diets (Fig. 3a, Cox proportional hazards: Likelihood ratio test = 2.09, d.f. = 2, P = 0.4). The survival of individuals that did not receive food for 2 days was slightly lower than that of individuals that received eggs of T. urticae or of T. evansi (Fig. 3a), but the majority of these individuals survived the two days without food.

The reversibility of the effect of a diet of T. evansi eggs in juvenile (a–c) and adult (d) predators. a–c: One day old larvae, which soon developed into the next stage, were kept on a diet of eggs of T. urticae, T. evansi or without food for two days (indicated by the grey background) and were subsequently reared to adulthood or until they died on a diet of T. urticae eggs (white background). a. Cumulative proportions (± s.e.) of juveniles on the three different diets surviving through time. b. Cumulative proportions (± s.e.) of juveniles reaching the adult stage through time. Letters next to final points indicate significance of difference in development among diets. c. The final stages reached by the juveniles as function of their diet, shown as a proportion of the initial numbers of individuals. d. Young adult females were offered a diet of T. urticae eggs during the first two days, then received no food, a diet of T. urticae eggs or a diet of T. evansi eggs during two days (grey background), and were then returned to a diet of T. urticae. Shown are average oviposition rates (± s.e.) of individuals on the three different diets through time. Letters near averages show significance of difference among treatments per day (contrasts after LME, P < 0.05, ns not significant)

The diet during the first two days of the protonymph stage significantly affected the developmental rate (Fig. 3b, Mantel–Heanszel test of Kaplan–Meier survival estimates: Chi2 = 29.4, d.f. = 2, P < 0.0001). Immatures that had fed continuously on T. urticae developed significantly faster into adults than immatures on the other diets (Fig. 3b). A few individuals that did not receive food during the first two days died as larva, some individuals without food and with T. evansi died as protonymph, some individuals feeding on T. urticae died as deutonymph, but the majority of individuals of this last group developed into adults (Fig. 3c). Juveniles offered a diet of T. evansi eggs consumed many more eggs than those with a diet of T. urticae eggs, but after having been offered T. urticae eggs, predation did not differ among the three treatment groups (Supp. Mat. S2, Fig. S2a).

Subsequently, we assessed the reversibility of the negative effects of feeding on T. evansi eggs for adult female predators. Survival of adult predators that received T. evansi (47.4%) or no food (47.6%) for two days was lower than that of predators on a diet of T. urticae (60.9%), but this difference was not significant (Cox proportional hazards: Likelihood ratio test = 2.05, d.f. = 2, P = 0.4). The numbers of predator eggs produced during the first two days, when all of them received eggs of T. urticae, did not differ significantly among groups during this period (Fig. 3d, Likelihood ratio = 1.59, d.f. = 2, P = 0.71). During the second period, the oviposition rates of the group of predators without food and that receiving eggs of T. evansi dropped significantly relative to that of the group with eggs of T. urticae, and the former two groups did not oviposit on the fourth day (Fig. 3d, LME, interaction treatment with time: likelihood ratio = 43.0, d.f. = 2, P < 0.0001). The oviposition on the first day after changing diet was again partially affected by the diet of the day before (Sabelis 1990). In the last period, all predators received eggs of T. urticae for another two days, and oviposition differed significantly among the three groups (Fig. 3d, LME, interaction of treatment with time: Likelihood ratio = 38.1, d.f. = 2, P < 0.0001). The groups that had been without food or with T. evansi started ovipositing again on day 5, and the oviposition rates of the groups that had fed on T. evansi or T. urticae did not differ from each other on day six (Fig. 3d). The predators that received T. evansi during two days consumed low numbers of this prey, but upon being switched back to a diet of T. urticae eggs, they resumed predation within one day, as did the predators that did not receive food during this period (Supp. Mat. S2, Fig. S2b). Together, these data show that the negative effects of a diet of T. evansi eggs on the performance of juvenile and adult predators are reversible and comparable to having no food.

Discussion

In summary, we show that feeding on T. evansi negatively affected the performance of the predatory mite P. persimilis. The negative effects were reversible when predators were feeding on the low-quality prey for short periods. We furthermore show that the adult predators did have a preference for T. urticae, the high-quality prey, but that they did not avoid feeding on the low-quality prey when ample high-quality prey was present.

Our results largely corroborate results by De Moraes and McMurtry (1985; 1986), who also found reduced oviposition and survival of P. persimilis on a diet of T. evansi. They observed that the predators often pierced the chorion of T. evansi eggs but apparently did not feed on them. The same may have occurred in our experiments, so the numbers of eggs reported as preyed here might be a combination of the actual numbers preyed and killed but not fed upon. It can be argued that this piercing of eggs would cost time and energy, resulting in the observed reduced performance of the mites when offered a diet with T. evansi. Phytoseiulus persimilis is mainly limited by the rate of digestion of prey and not by their encounter rate or the time spent handling prey (Sabelis 1990). If predators on a mixed diet would only have fed on the eggs of T. urticae, they would not have lost much time with piercing and rejecting eggs of T. evansi, so their performance on a mixed diet would not be significantly worse than on a diet of T. urticae only. We, therefore, conclude that the reduced performance on a mixed diet was caused by the ingestion of some toxic or digestibility-reducing factor present in the eggs of T. evansi.

The definition of high-quality prey by Toft and Wise (1999a) as prey that sustain development and reproduction and result in low mortality certainly applies to a diet of T. urticae. The strain of P. persimilis used here has been reared exclusively on this prey species for a long time, which may also have led to more adaptation to it. Toft and Wise (1999a) define toxic prey as one that causes higher mortality rates than in controls without food. According to this definition, T. evansi does not qualify as toxic for juvenile P. persimilis, as these showed a higher survival and some development on a diet of T. evansi than without food (Fig. 1a). However, adult predatory mites feeding on T. evansi had lower survival than those feeding on other diets and mortality increased with increasing numbers of T. evansi eggs consumed (Fig. 2b, c). Although there was no control without food included in this experiment, adult P. persimilis are known to survive for at least eight days without food as long as free water is available or when humidity is high (Bernstein 1983; Gaede 1992). Given that water was freely available during the experiments presented here, the lack of food would not have resulted in increased mortality during the experiments described here. Furthermore, the predators that died during the four days of the experiment had, on average, consumed more eggs of T. evansi per day than the mites that survived. We, therefore, conclude that T. evansi is, at least to some level, toxic to adult P. persimilis.

It has been suggested that predators feed on low-quality prey because they do not recognize them as such, but this then begs the question of why they do not. Predators can develop an aversion to toxic prey by learning the association between the harmful effects of the food and other compounds in the food, such as taste (Gelperin 1968; Berenbaum and Miliczky 1984; Fisker and Toft 2004; Rickers et al. 2006; Glendinning 2007; Nelson et al. 2011). In the case of the predator studied here, it is clear that the adult predators preferentially feed on the high-quality prey from the first day that they are offered a mixed diet (Fig. 2a), showing that they can discriminate between the two prey species. Yet, they persist in feeding on the low-quality prey to such an extent that it reduces their performance, at least during the experiments. Feeding on T. evansi for longer periods causes irreversible losses in fitness in juveniles (Fig. 1) and adults (Fig. 2), but when the predators fed on the low-quality prey for a period of only a few days, the negative effects could be partially reversed by feeding on high-quality prey afterwards (Fig. 3). For example, almost no juveniles became adults when feeding exclusively on T. evansi eggs (Fig. 1a, b), but most did so when feeding on T. evansi for a limited period (Fig. 3b, c). Although adult females can survive without food for at least 8 days when they have access to water (Bernstein 1983; Gaede 1992), they will stop ovipositing in the absence of prey. When food becomes available again, they can resume reproduction at the same level as before starvation (Sabelis 1981), and this is what was observed here for females without food and females feeding on T. evansi. Hence, avoiding feeding on T. evansi may not confer large fitness advantages initially, but will do so after longer periods. Perhaps the predators, therefore, need longer exposure to a mixture of high- and low-quality prey to develop an aversion. Phytoseiulus persimilis, however, is known to develop aversion or lack of attraction towards volatiles based on experience in one day (Drukker et al. 2000; de Boer et al. 2005; Zhang et al. 2022), and we suggest that similar learning capacities are present with respect to a combination of tactile and contact-chemical cues, possibly also combined with volatile cues. We, therefore, suspect that there is another reason for the sustained feeding on the low-quality prey, which will be discussed below.

Mixing the toxic prey with high-quality prey resulted in less severe effects on predator performance than feeding exclusively on the low-quality prey, which is in agreement with the toxin-dilution hypothesis. Such effects were found for toxic prey in several other studies (Toft 1995), but there seems to be no advantage of adding the low-quality prey to a diet of high-quality prey (Eubanks and Denno 1999; Toft and Wise 1999a, b; Bilde and Toft 2001; Oelbermann and Scheu 2002; Nielsen et al. 2002). Nevertheless, the predators in our experiments consumed T. evansi persistently in the presence of ample high-quality prey, as was also reported in other studies (De Moraes and McMurtry 1986; Snyder et al. 2000; Fisker and Toft 2004; Stamp and Meyerhoefer 2004; Rickers et al. 2006; Hinkelman and Tenhumberg 2013). The balanced diet hypothesis predicts that the performance of the predators on a mixed diet is better than on the single diets (Bilde and Toft 1994; Raubenheimer and Simpson 1997; Lefcheck et al. 2013), which was clearly not the case here. The lack of agreement with these two main hypotheses calls for further hypotheses on diet mixing.

Besides developing an aversion to low-quality food, another way of dealing with it is to ingest small quantities to induce detoxification systems or through selection for intestinal micro-organisms that can help in detoxification (Freeland and Janzen 1974; Nielsen et al. 2000; Fisker and Toft 2004), and perhaps this is what predators were doing in our experiments. As Freeland and Janzen (1974) suggest, such low-quality foods should be ingested with extreme caution, advice that is apparently lost on P. persimilis, which suffered consequences of ingesting low-quality food without reducing its intake over subsequent days. Perhaps longer-term exposure of the predator to mixtures of the two prey would result in either increased tolerance to the adverse effects of the low-quality prey or to increased aversion to it.

In their review of the effects of mixed diets, Lefcheck et al. (2013) argue that diet choice depends not only on prey quality, but also on prey densities and the risk of competition and predation. Furthermore, it is perhaps not the instantaneous oviposition rate on certain mixtures of prey or single prey that matters, but the total number of offspring and grand-offspring that is produced throughout the existence of a prey patch, especially for predators that spend several generations on one ephemeral patch. For example, Venzon et al. (2002) suggested that a predator’s prey choice was not determined by prey quality, but patch quality, i.e., the total number of offspring produced in a prey patch throughout its existence. The interaction between predatory mites and spider mites on a patch, consisting of a plant or group of neighbouring plants, typically lasts for several generations (Sabelis et al. 2002), and predators could perhaps adapt to toxins or digestibility reducers present in the low-quality prey in this period. Furthermore, consuming low-quality prey instead of high-quality prey may prolong the total interaction time of the predators and prey on a patch, resulting in the production of higher numbers of dispersing offspring (Pels and Sabelis 1999; Revynthi et al. 2018).

Another potential explanation for the persistent feeding of predators on low-quality prey, even in the presence of abundant high-quality prey, is that predators may often be food limited under natural conditions and, therefore, need to feed on these prey to survive adverse periods (Toft and Wise 1999a, b; Bilde and Toft 2001). In this case, feeding continuously on this low-quality prey perhaps induces the adaptation to this food, and may also result in increased performance under natural conditions in the long run. Contradicting this idea somewhat is the finding that exposure of P. persimilis to sublethal doses of acaricides did not seem to induce detoxification genes (Bajda et al. 2022), suggesting that such adaptation through detoxification may not readily occur in this predatory mite. Moreover, another, closely related predatory mite species, P. macropilis, co-occurs with T. evansi on tomato plants in Brazil, yet can still not reproduce when feeding on it (de Moraes and McMurtry 1985; Rosa et al. 2005), so it remains to be seen if predators can easily adapt to this prey species. Nevertheless, studies of mixed diets should consider testing the effects of diets under natural conditions when laboratory experiments show that they are suboptimal (Lefcheck et al. 2013).

Data availability

Upon publication of the ms, data will be made available on UvA/AUAS figshare.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Alba JM, Schimmel BCJ, Glas JJ et al (2015) Spider mites suppress tomato defenses downstream of jasmonate and salicylate independently of hormonal crosstalk. New Phytol 205:828–840. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.13075

Bajda SA, De Clercq P, Van Leeuwen T (2022) Selectivity and molecular stress responses to classical and botanical acaricides in the predatory mite Phytoseiulus persimilis Athias-Henriot (Acari: Phytoseiidae). Pest Manag Sci 78:881–895

Berenbaum MR, Miliczky E (1984) Mantids and milkweed bugs: efficacy of aposematic coloration against invertebrate predators. Am Midl Nat 111:64–68

Bernstein C (1983) Some aspects of Phytoseiulus persimilis [Acarina: Phytoseiidae] dispersal behaviour. Entomophaga 28:185–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02372143

Bilde T, Toft S (1994) Prey preference and egg production of the carabid beetle Agonum dorsale. Entomol Exp Appl 73:151–156

Bilde T, Toft S (2001) The value of three cereal aphid species as food for a generalist predator. Physiol Entomol 26:58–68

Bonato O (1999) The effect of temperature on life history parameters of Tetranychus evansi (Acari: Tetranychidae). Exp Appl Acarol 23:11–19

da Silva FR, de Moraes GJ, Gondim MG Jr et al (2010) Efficiency of Phytoseiulus longipes Evans as a control agent of Tetranychus evansi Baker & Pritchard (Acari: Phytoseiidae: Tetranychidae) on screenhouse tomatoes. Neotrop Entomol 39:991–995

de Moraes GJ, McMurtry JA (1985) Comparison of Tetranychus evansi and Tetranychus urticae [Acari, Tetranychidae] as prey for eight species of phytoseiid mites. Entomophaga 30:393–397

de Moraes G, McMurtry J (1986) Suitability of the spider mite Tetranychus evansi as prey for Phytoseiulus persimilis. Entomol Exp Appl 40:109–115

de Boer JG, Snoeren TAL, Dicke M (2005) Predatory mites learn to discriminate between plant volatiles induced by prey and nonprey herbivores. Anim Behav 69:869–879

de Oliveira EF, Pallini A, Janssen A (2016) Herbivores with similar feeding modes interact through the induction of different plant responses. Oecologia 180:1–10

de Vasconcelos GJN, de Moraes GJ, Delalibera I, Knapp M (2008) Life history of the predatory mite Phytoseiulus fragariae on Tetranychus evansi and Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Phytoseiidae, Tetranychidae) at five temperatures. Exp Appl Acarol 44:27–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-007-9124-8

Dicke M, Dijkman H (1992) Induced defense in detached uninfested plant-leaves—effects on behavior of herbivores and their predators. Oecologia 91:554–560. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00650331

Drukker B, Bruin J, Jacobs G et al (2000) How predatory mites learn to cope with variability in volatile plant signals in the environment of their herbivorous prey. Exp Appl Acarol 24:881–895

Escudero L, Ferragut F (2005) Life-history of predatory mites Neoseiulus californicus and Phytoseiulus persimilis (Acari: Phytoseiidae) on four spider mite species as prey, with special reference to Tetranychus evansi (Acari: Tetranychidae). Biol Control 32:378–384

Eubanks MD, Denno RF (1999) The ecological consequences of variation in plant and prey for an omnivorous insect. Ecology 80:1253–1266

Ferrero M, Tixier MS, Kreiter S (2014) Different feeding behaviors in a single predatory mite species. 1. Comparative life histories of three populations of Phytoseiulus longipes (Acari: Phytoseiidae) depending on prey species and plant substrate. Exp Appl Acarol 62:313–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-013-9745-z

Fisker EN, Toft S (2004) Effects of chronic exposure to a toxic prey in a generalist predator. Physiol Entomol 29:129–138

Freeland WJ, Janzen DH (1974) Strategies in herbivory by mammals: the role of plant secondary compounds. Am Nat 108:269–289. https://doi.org/10.2307/2459891

Furtado IP, de Moraes GJ, Kreiter S et al (2007) Potential of a Brazilian population of the predatory mite Phytoseiulus longipes as a biological control agent of Tetranychus evansi (Acari: Phytoseiidae: Tetranychidae). Biol Control 42:139–147

Gaede K (1992) On the water balance of Phytoseiulus persimilis A—H. and its ecological significance. Exp Appl Acarol 15:181–198

Gelperin A (1968) Feeding behaviour of the praying mantis: a learned modification. Nature 219:399–400

Glendinning JI (2007) How do predators cope with chemically defended foods? Biol Bull 213:252–266

Hinkelman TM, Tenhumberg B (2013) Larval performance and kill rate of convergent ladybird beetles, Hippodamia convergens, on black bean aphids, Aphis fabae, and pea aphids, Acyrthosiphon pisum. J Insect Sci 13:46. https://doi.org/10.1673/031.013.4601

Kant MR, Ament K, Sabelis MW et al (2004) Differential timing of spider mite-induced direct and indirect defenses in tomato plants. Plant Physiol 135:483–495

Kassambara A, Kosinski M, Biecek P (2020) survminer: drawing survival curves using “ggplot2”

Kennedy GG (2003) Tomato, pests, parasitoids, and predators: tritrophic interactions involving the genus Lycopersicon. Annu Rev Entomol 48:51–72

Knegt B, Meijer TT, Kant MR et al (2020) Tetranychus evansi spider mite populations suppress tomato defenses to varying degrees. Ecol Evol 10:4375–4390. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.6204

Koller M, Knapp M, Schausberger P (2007) Direct and indirect adverse effects of tomato on the predatory mite Neoseiulus californicus feeding on the spider mite Tetranychus evansi. Entomol Exp Appl 125:297–305

Lefcheck JS, Whalen MA, Davenport TM et al (2013) Physiological effects of diet mixing on consumer fitness: a meta-analysis. Ecology 94:565–572

Lenth R (2019) emmeans: estimated marginal means, aka Least-Squares Means. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans

Mayntz D, Raubenheimer D, Salomon M et al (2005) Nutrient-specific foraging in invertebrate predators. Science 307:111–113

Migeon A, Dorkeld F (2020) Spider mites web: a comprehensive database for the Tetranychidae. https://www1.montpellier.inra.fr/CBGP/spmweb/

Navajas M, de Moraes GJ, Auger P, Migeon A (2013) Review of the invasion of Tetranychus evansi: biology, colonization pathways, potential expansion and prospects for biological control. Exp Appl Acarol 59:43–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-012-9590-5

Nelson DW, Crossland MR, Shine R (2011) Foraging responses of predators to novel toxic prey: effects of predator learning and relative prey abundance. Oikos 120:152–158

Nielsen SA, Hauge MS, Nielsen FH, Toft S (2000) Activities of glutathione S-transferase and glutathione peroxidases related to diet quality in an aphid predator, the seven-spot ladybird, Coccinella septempunctata L. (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Altern Lab Anim 28:445–449

Nielsen FH, Hauge MS, Toft S (2002) The influence of mixed aphid diets on larval performance of Coccinella septempunctata (Col., Coccinellidae). J Appl Entomol 126:194–197. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1439-0418.2002.00629.x

Oelbermann K, Scheu S (2002) Effects of prey type and mixed diets on survival, growth and development of a generalist predator, Pardosa lugubris (Araneae : Lycosidae). Basic Appl Ecol 3:285–291. https://doi.org/10.1078/1439-1791-00094

Pallini A, Janssen A, Sabelis MW (1998) Predators induce interspecific herbivore competition for food in refuge space. Ecol Lett 1:171–177. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1461-0248.1998.00019.x

Pels B, Sabelis MW (1999) Local dynamics, overexploitation and predator dispersal in an acarine predator-prey system. Oikos 86:573–583

Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, et al (2020) NLME: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. In: HttpCRANR-Proj. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme

Pulliam HR (1975) Diet optimization with nutrient constraints. Am Nat 109:765–768

R Core Team (2020) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Version 4.0.2. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL http://www.R-project.org

Raubenheimer D, Simpson SJ (1997) Integrative models of nutrient balancing: application to insects and vertebrates. Nutr Res Rev 10:151–179

Revynthi AM, Egas M, Janssen A, Sabelis MW (2018) Prey exploitation and dispersal strategies vary among natural populations of a predatory mite. Ecol Evol 8:10384–10394

Rickers S, Langel R, Scheu S (2006) Dietary routing of nutrients from prey to offspring in a generalist predator: effects of prey quality. Funct Ecol 20:124–131

Rosa AA, Gondim MGC, Fiaboe KKM et al (2005) Predatory mites associated with Tetranychus evansi Baker & Pritchard (Acari : Tetranychidae) on native solanaceous plants of coastal Pernambuco State, Brazil. Neotrop Entomol 34:689–692

Sabelis MW (1981) Biological control of two-spotted spider mites using phytoseiid predators. Pudoc Wageningen, The Netherlands

Sabelis MW (1990) How to analyze prey preference when prey density varies? A new method to discriminate between effects of gut fullness and prey type composition. Oecologia 82:289–298

Sabelis MW, van Baalen M, Pels B et al (2002) Evolution of exploitation and defense in tritrophic interactions. In: Dieckmann U, Metz JA, Sabelis MW, Sigmund K (eds) Adaptive dynamics of infectious diseases: In pursuit of virulence management. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 297–321

Sarmento RA, Lemos F, Bleeker PM et al (2011a) A herbivore that manipulates plant defence. Ecol Lett 14:229–236

Sarmento RA, Lemos F, Dias CR et al (2011b) A herbivorous mite down-regulates plant defence and produces web to exclude competitors. PLoS ONE 6(1–7):e23757

Snyder WE, Joseph SB, Preziosi RF, Moore AJ (2000) Nutritional benefits of cannibalism for the lady beetle Harmonia axyridis (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) when prey quality is poor. Environ Entomol 29:1173–1179

Stamp N, Meyerhoefer B (2004) Effects of prey quality on social wasps when given a choice of prey. Entomol Exp Appl 110:45–51

Stenseth C (1979) Effect of temperature and humidity on the development of Phytoseiulus persimilis and its ability to regulate populations of Tetranychus urticae [Acarina: Phytoseiidae, Tetranychidae]. Entomophaga 24:311–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02374246

Takafuji A, Chant DA (1976) Comparative studies of two species of predaceous phytoseiid mites with special reference to the density of their prey. Res Popul Ecol 17:255–310

Therneau TM (2015) COXME: mixed effects Cox models

Therneau TM (2020) A package for survival analysis in R. Version R package version 3.1–124URL https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival

Toft S (1995) Value of the aphid Rhopalosiphum padi as food for cereal spiders. J Appl Ecol 32:552–560

Toft S, Wise DH (1999a) Growth, development, and survival of a generalist predator fed single- and mixed-species diets of different quality. Oecologia 119:191–197

Toft S, Wise DH (1999b) Behavioral and ecophysiological responses of a generalist predator to single- and mixed-species diets of different quality. Oecologia 119:198–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004420050777

van Lenteren JC (2012) The state of commercial augmentative biological control: plenty of natural enemies, but a frustrating lack of uptake. Biocontrol 57:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10526-011-9395-1

Venzon M, Janssen A, Sabelis MW (2002) Prey preference and reproductive success of the generalist predator Orius laevigatus. Oikos 97:116–124

Zhang NX, Andringa J, Brouwer J et al (2022) The omnivorous predator Macrolophus pygmaeus induces production of plant volatiles that attract a specialist predator. J Pest Sci 95:1343–1355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-021-01463-3

Acknowledgements

We thank Ludek Tikovsky, Harold Lemereis and T. Hendrix for taking care of the plants in the greenhouse, Merijn Kant, and Marco van Weij for discussions on experimental planning. The authors also thank the colleagues from the Laboratory of Acarology of the Federal University of Viçosa and the Population Biology group of the University of Amsterdam for discussions. FL was financially supported by CNPq (140951/2011-3), Capes (BEX 11499/12-5) and NWO (TOP Project 854.11.005). SB is a post-doctoral researcher supported by ERANET, C-IPM, Grant No. 618110. The ms benefitted greatly from the comments of two anonymous reviewers.

Funding

The research was funded by CNPq and Capes (Brazil), NWO (the Netherlands) and ERANET (EU).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FL, SB, AJ, MVDD, TVL, AP and MWS conceived and designed research. FL, SB, MVAD and JMA conducted experiments. FL and AJ analyzed data. FL and AJ wrote the manuscript. All authors except MWS (deceased) read, corrected and approved the manuscript. The wife of the deceased, Dr Isa Sabelis Lesna approved submission of the ms.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

All applicable international, national, and institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed. This article does not contain any studies with human participants.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Communicated by Liliane Ruess.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lemos, F., Bajda, S., Duarte, M.V.A. et al. Imperfect diet choice reduces the performance of a predatory mite. Oecologia 201, 929–939 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-023-05359-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-023-05359-0