Abstract

This study aims to investigate the relationship between motor skills at age 7 and spinal pain at age 11. The study included participants from the Danish National Birth Cohort. Data on motor skills were obtained from the Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire, completed by the mothers when the children were 7 years old, and spinal pain was self-reported at age 11 for frequency and intensity of neck, mid back, and low back pain. This was categorized into “no,” “moderate,” or “severe” pain, based on frequency and pain intensity. Associations were estimated using multinomial logistic regression models. Data on both motor skills and spinal pain was available for 25,000 children. There was a consistent pattern of reporting more neck or mid back pain at age 11 for those with lower levels of fine motor skills and coordination scores at age 11. The relationship was significant for severe pain (the highest relative risk ratio being 1.87 and the lowest 1.18), but not for moderate pain (the highest relative risk ratio being 1.22 and the lowest 1.07). Gross motor skills were not associated with spinal pain, and there was no relationship between low back pain and motor skills.

Conclusion: Our results indicate a link between motor development at 7 years of age and neck and mid back pain, but not low back pain, at 11 years of age. Improvement of motor skills in young children might reduce the future burden of neck and mid back pain and should be a target of future research.

What is Known: |

• Spinal pain in preadolescence and adolescence is common and predisposes to spinal pain in adulthood. |

• Motor skills influence the biomechanics of movement and therefore has a potential impact on musculoskeletal health. |

What is New: |

• Poor fine motor- and coordination skills in childhood were associated with increased risk of severe neck- or mid back pain, but not low back pain, four 4 years later. |

• Poor gross motor skills were not associated with higher risk of later spinal pain. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Back and neck pain are major contributors to the global burden of disease [1] and the most common somatic reasons for disability pension in Scandinavia [2, 3]. It is often considered as a problem relating to the working age population, but research has shown that it can have its onset already early in life [4,5,6], that prevalence approaches adult levels around the age of 18 [7, 8], and that teenagers with back pain are likely to become adults with back pain [9]. Therefore, it is essential to identify risk factors predisposing to spinal pain early in life to improve our chances for prevention [5].

Good motor skills are considered important for children’s physical, social, and psychological development. Motor skills are also important for an active lifestyle, since several studies have shown a positive association between good motor skills and higher levels of physical activity [10,11,12]. Consequently, there is evidence of many health benefits to be gained from an improvement in motor skills. For instance, it has been demonstrated that good motor skills positively influence cardiorespiratory fitness [10, 13], body weight [10, 14,15,16], and sports participation [10, 16], all suggesting that early competency in motor skills may have important health implications.

There is also reason to believe that motor skills may be associated with musculoskeletal problems as motor skills are the ability to perform certain tasks such as walking or catching a ball, which in turn is highly dependent on both balance (the ability to stay upright or stay in control of body movement) and coordination (the ability to move two or more body parts under control, smoothly, and effectively). The level of motor skills strongly influences motor performance, i.e., the ability to perform tasks involving movement. Motor performance in children with Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD) is usually slower, less accurate, and more variable than in their peers. Motor learning is also impacted, with children with DCD having difficulty acquiring skills typically learned during childhood, such as tying shoes or riding a bicycle [17]. Physical education can also be affected, as children with DCD have trouble throwing, catching, or kicking a ball, running, skipping, and playing sports [17]. Age-appropriate balance and coordination allows the child to be involved in sports participation with a reasonable degree of success as it aids fluid body movement for physical skill performance (e.g. walking a balance beam or playing football), and therefore, it is likely that both quantity and quality of physical activity are affected in children with poor coordination, even if they do not meet the criteria for DCD. With good balance and coordination, there is less likelihood of injury as the child is likely to have appropriate postural responses when needed (e.g. putting hands out to protect themselves when falling of a bike). The physical attributes of balance and coordination also allow appropriate biomechanical function of the musculoskeletal system and thus reduces the risk of inappropriate load of joints.

Furthermore, children with DCD engage in fewer physical and group activities than their peers, perhaps as a reflection of their poorer athletic performance and social competence, and this can lead to social isolation [17], which has also been observed in children with spinal pain [4, 18, 19]. Again, as levels of coordination and motor skills are based on a continuum, is it reasonable to assume that the same mechanisms are present in children with a lesser degree of coordination impairment, i.e., not reaching the threshold for DCD.

The presence of a link between spinal pain and motor coordination and/or motor skills is supported by intervention studies, which have shown that focused motor skills training can increase muscle control, coordination, and balance in adults and decrease back pain–related disability compared to other types of exercise [20, 21]. Good motor control has also been shown to reduce the frequency of musculoskeletal injuries in the extremities [22,23,24], which again might help to reduce spinal pain, as two studies have shown an increased occurrence of spinal pain in case of lower extremity pain [25, 26].

Given that motor delay observed in childhood are still apparent in adolescence [27], it is possible that development of motor skills early in life may influence the onset, or the maintenance, of spinal pain in childhood. Our group has previously conducted a large study of motor mile stones and found no association between age of unsupported sitting and independent walking and later spinal pain [28]. However, a link between motor coordination in childhood and the development of back and neck pain has not been investigated.

This study is an extension of the previous study [28], taking advantage of the extensive database in the Danish National Birth Cohort to investigate a potential relationship between motor development in childhood and spinal pain in preadolescence. Specifically, we estimated the magnitude of the relationship between motor coordination at 7 years of age and the presence of spinal pain (SP) at 11 years of age.

Material and methods

Population and data collection

The Danish National Birth Cohort (DNBC) began as a survey of pregnant women in Denmark. Between 1996 and 2002, pregnant women were invited to enrol in the cohort at their first antenatal visit to the general practitioner. Women were included if they intended to carry the pregnancy to term and spoke Danish well enough to complete telephone interviews. Assessment of participants was conducted with interview surveys of the mothers, while the participants were in utero and again at the ages of 6 and 18 months, as well as maternal questionnaires when the children were around 7 years of age. Surveys included a range of socio-demographic, anthropometric, health-related, and behavioural variables of both mothers and children as well as motor development.

A follow-up was planned for the year the children turned 11, where a questionnaire was distributed by mail and completed by the children themselves. However, administration of the questionnaires was somewhat irregular, and therefore, the age ranges from 10 to 14, but with the majority being 11 years of age at the time of questionnaire completion (henceforth called age 11 for readability). The questionnaire included data on spinal pain.

The target sample for the analyses in this study consisted of liveborn singletons included in the DNBC. Children were included in the analyses if their mothers had completed the 7-year survey, including questions about motor skills, and the children themselves had answered the questions about spinal pain at age 11. However, if children have serious physical or developmental problems, they are very likely to experience developmental delay as well as later spinal pain, and thus, a potential relationship could be driven by these children. Therefore, children were excluded from the analyses if their mothers answered positive to the question “The following questions are about what your child can do right now, but first I need to know if he/she has any serious physical or developmental problems? “ at the 18-month interview.

The Danish National Birth Cohort is presented in detail elsewhere [29].

Variables

Exposure: motor development at seven years of age (questionnaire completed by the mother)

The Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire (DCDQ) was used to assess motor development at age seven. Parents were asked to assess 15 statements related to their child as compared to other children of the same age and sex. Each question had five response options: (1) “not true,” (2) “a little true,” (3) “fairly true,” (4) “true,” and (5) “very true,” giving a maximum score of 75. The scoring is divided into subscales for three domains: statements 1–6 (max 30 points) evaluating “control during movement,” statements 7–10 (max 20 points) evaluating “fine motor/handwriting,” and statements 11–15 (max 25 points) about “general coordination.”

The DCDQ was developed to screen for Developmental Coordination Disorder [30] and has been validated for use with 7-year-old children [31, 32].

Outcome: spinal pain (questionnaire completed by the child at age 11)

The Young Spine Questionnaire (YSQ) includes assessment of presence, frequency, and intensity of neck pain, mid back pain, and low back pain. The YSQ was developed for and tested among 5–12-years old and is described elsewhere [33]. The exact wording of the frequency questions was “How often have you had pain in your neck/middle back/low back,” with four response categories: “often”, “once in a while,” “once or twice,” and “never.” Respondents that had experienced pain were requested to rate the pain intensity by means of The Revised Faces Pain Scale (rFPS), ranging from 1 (“Not at all”) to 6 (“Really very much”).

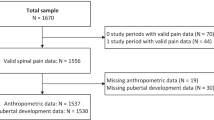

To distinguish between trivial and non-trivial pain, we combined pain frequency and intensity for each spinal region into “no pain,” “moderate pain,” or “severe pain,” in the same manner as in a previous study of the same cohort [34]. The optimal cut-point for consequential spinal pain in children is presently unknown but based on findings from previous studies of children in this age group [35]; also, using the YSQ, severe pain was defined as pain of four or more on the Faces Pain Scale-Revised [36] and occurring at least “once in a while.” No pain was defined as “never” or “once or twice”/”once in a while” with pain intensity below 3. Exact classification of pain groups appears from Fig. 1. Overall spinal pain was defined as a composite variable including the three spinal regions. If the reported pain differed between the three spinal locations, the location with the most severe pain was used.

The primary outcomes are moderate and severe spinal pain at 11 years of age, and secondary outcomes are pain in the three areas of the spine separately, i.e., neck pain, mid back pain, and low back pain.

Confounders

In the previous study, investigating the relationship between motor milestones and later spinal pain [28], sex, birthweight, maternal smoking during pregnancy, maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy, household income, and mother’s level of schooling (20 response options categorized into four levels [37]) were found to be confounders for at least one spinal region. Therefore, they were a priori selected to be included in the present analyses.

Furthermore, overweight or excess body fat has been found to increase the risk of both poor motor skills [38] and spinal pain, also in children [39], and therefore, height and weight at baseline were also included as potential confounders.

All of these confounders were reported by the mother at various follow-up times, except birth weight, which was obtained from the Danish Medical Birth Register [40].

For the exact wording of questions and response options, see Supplementary Material 1.

Analyses

To assess representativeness, the study samples for univariate and adjusted analyses were compared to the original cohort with respect to exposure, outcomes, and confounders.

Continuous data were reported as means with standard deviations (SD) and dichotomous and categorical data as absolute numbers and proportions.

At 7 years of age, the DCDQ scores were very skewed with a marked ceiling effect. Therefore, based on visual inspection of the distribution, the total score and all subscales were divided into three categories for interpretation:

-

3 = the lowest 10% (poorest development of motor skills) which is the validated cut-point for DCD [32].

-

2 = above the tenth percentile but below maximum score.

-

1 = maximum score (best development of motor skills).

The relationship between motor skills and later spinal pain was depicted graphically by showing the prevalence of all spinal pain (moderate and severe combined) by motor skills categories before estimates of associations were calculated. The associations between the exposure (DCDQ) and the outcomes (severe and moderate spinal pain, neck pain, mid back pain, and low back pain) were estimated by multinominal logistic regression, adjusted for all potential confounders. Stata 16 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA) was used for all analyses, and significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

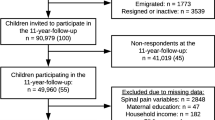

In total, 91,848 liveborn singletons without serious physical or mental problems were included in the DNBC between 1996 and 2003. The mothers of 54,439 children (59% of the original cohort) completed the survey when the child was 7 years of age. The 11-year follow-up was completed by 47,830 children, of which the mothers had completed the DCDQ for 26,382. Of these, 25,084 (28% of the original cohort) answered the YSQ and were included in the unadjusted analyses. To be included in the adjusted analyses, data for all covariates were required, leaving 16,921 children for these analyses (Fig. 2). Our samples differed slightly from the original cohort by being less disadvantaged on almost all parameters (i.e., higher birthweight, higher gestational age, less maternal smoking, less maternal alcohol consumption, higher education, higher income, and less spinal pain). However, all differences were very small and there were no differences in the exposure (DCDQ) (Table 1).

Almost one-third (29%) reported moderate spinal pain, and 11% severe spinal pain. The most common pain region was the neck (both moderate and severe), and for all regions, the prevalence was about three times higher for moderate pain than for severe pain (Table 1).

DCDQ scores were strongly skewed (Fig. 3). The tenth percentile (cut point between category 3 and 2) was 56 for the total DCDQ score, 21 for the gross motor skills subscale, 14 for the fine motor skill subscale, and 17 for the coordination subscale.

Distribution of DCDQ scores for the total score, gross motor skills, fine motor skills, and coordination at age 7. DCDQ: Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire at the age of seven years; score: total score; gross: subscale for gross motor skills; fine: subscale for fine motor skills; coor: subscale for coordination

Association with spinal pain

The graphs in Fig. 4 generally show an increasing frequency of spinal pain at age 11 with increasing motor difficulties at age 7, but the differences are small (please note the scale on the y-axis). Results were similar for neck pain and mid back pain, whereas no relationship was seen with low back pain. Graphs by region can be seen in Supplementary Material 2.

Prevalence of spinal pain (moderate and severe combined) at age 11 by categories* of motor skills at age 7; 95% confidence interval. *1: maximum score, 2: above the tenth percentile but below maximum score; 3: the lowest 10 percent. SP2: moderate and severe spinal pain combined; DCDQ: Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire at the age of seven; totcat: categories for total score; grosscat: categories for subscale for gross motor skills; finecat: categories for subscale for fine motor skills; coorcat: categories for subscale for coordination

There were slightly increased relative risk ratios (RRR) for moderate spinal pain, neck pain, and mid back pain at age 11 with lower DCDQ scores at age 7. The relationship was consistent but weak with RRR ranging from 1.07 to 1.22 for children with the lowest levels of motor skills and was generally not statistically significant. There was no association with low back pain (Table 2).

The associations were stronger for severe spinal pain than for moderate pain. There was consistently increased RRRs for spinal pain, neck pain, and mid back pain, with decreasing DCDQ scores. The associations ranged from 1.04 to 1.87 and were statistically significant in 19 of the 24 estimated associations. There were no associations with low back pain (Table 3).

The relationship was driven by the subscales for fine motor skills and coordination with no or weak associations for gross motor skills. The highest estimated relative risk ratio was 1.87 (95% CI:1.34–2.61) for development of severe mid back pain in the group with poorest coordination (Tables 2 and 3).

Discussion

We found a consistent pattern of more reporting of neck or mid back pain at age 11 with poorer motor skills scores at age 7. The relationship was stronger for severe than for moderate pain, but all estimates were small and only statistically significant for severe pain. There was no relationship with low back pain.

According to the recent review by Noll et al. [41], only two studies have investigated the influence of balance on back pain in children and adolescents: a prospective study of balance at age 16 and back pain at age 34, and a cross-sectional study of balance and back pain the past week in children aged 8–12 years. Neither of the two found an association, but as one did not report paediatric spinal pain and the other was cross-sectional, results are difficult to relate to the present study. To our knowledge, other domains of motor skills have not been investigated in relation to spinal pain in children.

A major strength of this study is the large general population-based sample. Almost one-third of all pregnant women in Denmark in the years from 1996 to 2002 were enrolled in the DNBC cohort (29) and 55% of the invited children responded to the 11-year follow-up. Nevertheless, attrition is substantial, and pregnant women who participated in the DNBC were generally healthier and had higher socioeconomic status than women who did not participate [42]. The differential drop out pattern could induce participation bias, as children of parents with lower socioeconomic status and shorter education have higher incidence of back pain [43, 44]. However, although only 28% of the original cohort is included in the final analyses, we believe the possible attrition bias is limited since adding confounders to the model did not change the estimates (unadjusted estimates not shown) and the prevalence of spinal pain was similar to those found in another Danish study investigating the same age group with the same instrument (YSQ) but with response rates above 90% [35]. Furthermore, Greene et al. found minimal influence of attrition bias on selected associations in the DNBC cohort [45] and prevalence of spinal pain with inverse probability weighting to resemble the general Danish population has shown similar rates as the final sample in this study [34].

The self-reported measure of back pain could create some concern. However, although back pain in childhood was previously considered rare and a sign of serious underlying pathology, more recent studies have indicated that the condition is common, and it is usually not possible to diagnose a specific patho-anatomical cause for the pain, suggesting that the vast majority of spinal pain is non-specific. In that light, the self-reports of pain are probably the best option.

The most important limitation of this study is the measurements of motor skills. The DCDQ was originally developed to detect children with motor skills deficiencies [32] and is therefore better to differentiate among poor performers than across a normal range of children. This was illustrated by high sensitivity demonstrated in clinical samples but not in population-based samples [30] and was also clear by the strong ceiling effect in our sample with more than 80% of mothers answering positively to most questions.

Our results should trigger more research into the area of motor skills as a potential vehicle for prevention of development of spinal pain in the young population. However, future studies should use instruments developed to describe motor skills in normal populations. Furthermore, the prevalence of spinal pain is still low at age 11 compared to older adolescents, especially for low back pain which represents the largest burden in adults, and therefore investigations with longer follow-up are needed.

Conclusion

Our results indicate a link between motor development as measured by the DCDQ at 7 years of age and neck and mid back pain at 11 years of age. The relationship was driven by the subscales of coordination and fine motor skills, whereas associations with “control of movement” were weak or non-existent. No associations with low back pain were detected. Thus, improvement of motor skills in young children might reduce the future burden of neck and mid back pain and should be a target of future research.

Abbreviations

- DNBC:

-

The Danish National Birth Cohort

- DCDQ:

-

Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire

- rFPS:

-

Revised Faces Pain Scale

- RRR:

-

Relative risk ratio

- SP:

-

Spinal pain (neck pain, mid back pain and/or low back pain)

- YSQ:

-

The Young Spine Questionnaire

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

References

Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 (2016). Lancet 388(10053):1545–602

(Försäkringskassan) SIA (2002) Vad kostar olika sjukdomar? -sjukpenningkostnader fördelade efter sjukskrivningsdiagnos. Stockholm Sweden

Flachs EM EL, Koch MB, Ryd JT, Dibba E, Ettrup L, Juel K (2015) Sygdomsbyrden i Danmark. In: Statens Institut for folkesundhed, editor. København: Sundhedsstyrelsen

Kamper SJ, Yamato TP, Williams CM (2016) The prevalence, risk factors, prognosis and treatment for back pain in children and adolescents: an overview of systematic reviews. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 30(6):1021–1036

Dunn KM, Hestbaek L, Cassidy JD (2013) Low back pain across the life course. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 27(5):591–600

Hoy D, Bain C, Williams G, March L, Brooks P, Blyth F et al (2012) A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis Rheum 64(6):2028–2037

Calvo-Munoz I, Gomez-Conesa A, Sanchez-Meca J (2013) Prevalence of low back pain in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr 13:14

Jeffries LJ, Milanese SF, Grimmer-Somers KA (2007) Epidemiology of adolescent spinal pain: a systematic overview of the research literature. Spine 32(23):2630–2637

Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Kyvik KO, Manniche C (2006) The course of low back pain from adolescence to adulthood: eight-year follow-up of 9600 twins. Spine 31(4):468–472

Lubans DR, Morgan PJ, Cliff DP, Barnett LM, Okely AD (2010) Fundamental movement skills in children and adolescents: review of associated health benefits. Sports Med 40(12):1019–1035

Fisher A, Reilly JJ, Kelly LA, Montgomery C, Williamson A, Paton JY et al (2005) Fundamental movement skills and habitual physical activity in young children. Med Sci Sports Exerc 37(4):684–688

Williams HG, Pfeiffer KA, O’Neill JR, Dowda M, McIver KL, Brown WH et al (2008) Motor skill performance and physical activity in preschool children. Obesity (Silver Spring) 16(6):1421–1426

Okely AD, Booth ML, Patterson JW (2001) Relationship of physical activity to fundamental movement skills among adolescents. Med Sci Sports Exerc 33(11):1899–1904

Morano M, Colella D, Caroli M (2011) Gross motor skill performance in a sample of overweight and non-overweight preschool children. International journal of pediatric obesity : IJPO : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity 6(Suppl 2):42–46

D’Hondt E, Deforche B, Vaeyens R, Vandorpe B, Vandendriessche J, Pion J et al (2011) Gross motor coordination in relation to weight status and age in 5- to 12-year-old boys and girls: a cross-sectional study. International journal of pediatric obesity : IJPO : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity 6(2–2):e556–e564

Krombholz H (2013) Motor and cognitive performance of overweight preschool children. Percept Mot Skills 116(1):40–57

Zwicker JG, Missiuna C, Harris SR, Boyd LA (2012) Developmental coordination disorder: a review and update. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 16(6):573–581

Lauridsen HH, Stolpe AB, Myburgh C, Hestbaek L (2020) What are important consequences in children with non-specific spinal pain? A qualitative study of Danish children aged 9–12 years. BMJ Open 10(10):e037315

Batley S, Aartun E, Boyle E, Hartvigsen J, Stern PJ, Hestbaek L (2019) The association between psychological and social factors and spinal pain in adolescents. Eur J Pediatr 178(3):275–286

van Dillen LR, Lanier VM, Steger-May K, Wallendorf M, Norton BJ, Civello JM et al (2021) Effect of Motor Skill Training in Functional Activities vs Strength and Flexibility Exercise on Function in People With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol 78(4):385–395

Aasa B, Berglund L, Michaelson P, Aasa U (2015) Individualized low-load motor control exercises and education versus a high-load lifting exercise and education to improve activity, pain intensity, and physical performance in patients with low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 45(2):77–85

Schiftan GS, Ross LA, Hahne AJ (2014) The effectiveness of proprioceptive training in preventing ankle sprains in sporting populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sci Med Sport / Sports Med Australia

Parkkari J, Taanila H, Suni J, Mattila VM, Ohrankammen O, Vuorinen P et al (2011) Neuromuscular training with injury prevention counselling to decrease the risk of acute musculoskeletal injury in young men during military service: a population-based, randomised study. BMC Med 9:35

Pasanen K, Parkkari J, Pasanen M, Hiilloskorpi H, Makinen T, Jarvinen M et al (2008) Neuromuscular training and the risk of leg injuries in female floorball players: cluster randomised controlled study. BMJ 337:a295

Seay JF, Shing T, Wilburn K, Westrick R, Kardouni JR (2018) Lower-extremity injury increases risk of first-time low back pain in the US Army. Med Sci Sports Exerc 50(5):987–994

Fuglkjaer S, Vach W, Hartvigsen J, Wedderkopp N, Junge T, Hestbaek L (2018) Does lower extremity pain precede spinal pain? A longitudinal study Eur J Pediatr 177(12):1803–1810

Cantell MH, Smyth MM, Ahonen TP (1994) Clumsiness in adolescence: educational, motor, and social outcomes of motor delay detected at 5 years Adapted Phys Activity Quart 11:115–29

Kamper SJ, Williams CM, Hestbaek L (2017) Does Motor Development in Infancy Predict Spinal Pain in Later Childhood? A Cohort Study. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 47(10):763–768

Olsen J, Melbye M, Olsen SF, Sorensen TI, Aaby P, Andersen AM et al (2001) The Danish National Birth Cohort—its background, structure and aim. Scand J Public Health 29(4):300–307

Schoemaker MM, Flapper B, Verheij NP, Wilson BN, Reinders-Messelink HA, de Kloet A (2006) Evaluation of the Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire as a screening instrument. Dev Med Child Neurol 48(8):668–673

Wilson BN, Crawford SG, Green D, Roberts G, Aylott A, Kaplan BJ (2009) Psychometric properties of the revised Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr 29(2):182–202

Wilson BN, Kaplan BJ, Crawford SG, Campbell A, Dewey D (2000) Reliability and validity of a parent questionnaire on childhood motor skills. Am J Occup Ther 54(5):484–493

Lauridsen HH, Hestbaek L (2013) Development of the young spine questionnaire. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 14:185

Joergensen AC, Hestbaek L, Andersen PK, Nybo Andersen AM (2019) Epidemiology of spinal pain in children: a study within the Danish National Birth Cohort. Eur J Pediatr 178(5):695–706

Aartun E, Hartvigsen J, Wedderkopp N, Hestbaek L (2014) Spinal pain in adolescents: prevalence, incidence, and course: a school-based two-year prospective cohort study in 1,300 Danes aged 11–13. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 15:187

Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, Spafford PA, van Korlaar I, Goodenough B (2001) The Faces Pain Scale-Revised: toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement. Pain 93(2):173–183

ISCED (2012) International standard classification of education ISED2011. UNESO Institute for Statistics, Montreal, Canada: UNESO Institute for Statistics, Montreal

Nobre JNP, Morais RLS, Fernandes AC, Viegas AA, Figueiredo PHS, Costa HS et al (2022) Is body fat mass associated with worse gross motor skills in preschoolers? An exploratory study. PLoS ONE 17(3):e0264182

Shiri R, Karppinen J, Leino-Arjas P, Solovieva S, Viikari-Juntura E (2010) The association between obesity and low back pain: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 171(2):135–154

Bliddal M, Broe A, Pottegård JA, Olsen J (2018) Danish Medical Birth Register. Eur J Epidemiol 33(1):27–36

Noll M, Kjaer P, Mendonca CR, Wedderkopp N (2022) Motor performance and back pain in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Eur J Pain 26(1):77–102

Nohr EA, Frydenberg M, Henriksen TB, Olsen J (2006) Does low participation in cohort studies induce bias? Epidemiology 17(4):413–418

Mustard CA, Kalcevich C, Frank JW, Boyle M (2005) Childhood and early adult predictors of risk of incident back pain: Ontario Child Health Study 2001 follow-up. Am J Epidemiol 162(8):779–786

Hestbaek L, Korsholm L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Kyvik KO (2008) Does socioeconomic status in adolescence predict low back pain in adulthood? A repeated cross-sectional study of 4,771 Danish adolescents. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society 17(12):1727–1734

Greene N, Greenland S, Olsen J, Nohr EA (2011) Estimating bias from loss to follow-up in the Danish National Birth Cohort. Epidemiology 22(6):815–822

Acknowledgements

The Danish National Birth Cohort was established with a significant grant from the Danish National Research Foundation. Additional support was obtained from the Danish Regional Committees, the Pharmacy Foundation, the Egmont Foundation, the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation, the Health Foundation, and other minor grants. The DNBC Biobank has been supported by the Novo Nordisk Foundation and the Lundbeck Foundation. Follow-up of mothers and children have been supported by the Danish Medical Research Council (SSVF 0646, 271-08-0839/06-066023, O602-01042B, 0602-02738B), the Lundbeck Foundation (195/04, R100-A9193), The Innovation Fund Denmark 0603-00294B (09-067124), the Nordea Foundation (02-2013-2014), Aarhus Ideas (AU R9-A959-13-S804), University of Copenhagen Strategic Grant (IFSV 2012), and the Danish Council for Independent Research (DFF-4183-00594 and DFF-4183-00152).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Royal Danish Library.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LH conceptualized and designed the study; LH, SK, ACJ, and JH contributed to method development including operationalization of variables; LH and ACJ carried out data management and analyses. LH drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to interpretation of results and intellectual content, and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclaimer

The funder/sponsor did not participate in the work.

Ethics approval

The Danish National Birth Cohort was initially approved by the Copenhagen Committee on Biomedical Research Ethics under ref. no (KF) 01-471/94 and by the Danish Data Protection Agency under ref. no 2012-54-0268. As from the 22nd September 2015, the Statens Serum Institut is responsible for the DNBC under the institute’s general approval covering research projects, ref. no 2015-57-0102. An informed consent procedure is not required in order to carry out a data collection among DNBC participants. The subsequent follow-up waves in the DNBC have therefore been approved solely by the Danish Data Protection Agency, as they involve the collection of data only. The 11-year data collection is approved under 2013-41-2364. Approval of the present analyses was obtained from the DNBC Steering Committee, and no personally identifiable data were available.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Communicated by Gregorio Milani.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hestbæk, L., Kamper, S.J., Hartvigsen, J. et al. Motor skills at 7 years of age and spinal pain at 11 years of age: a cohort study of 26,000 preadolescents. Eur J Pediatr 182, 2843–2853 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-023-04964-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-023-04964-8