Abstract

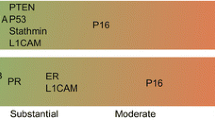

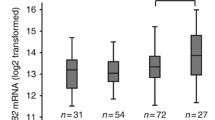

The accurate distinction between primary endocervical adenocarcinomas (ECA) and endometrial adenocarcinomas (EMA) may require the use of multiple ancillary monoclonal antibodies in panels of immunohistochemistry stains. In addition to reappraising the expressions of four commonly used individual monoclonal antibodies [estrogen receptor (ER), Vimentin (Vim), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and p16INK4], this study was designed to investigate whether CEA and p16INK4 can be effectively exchanged between two relevant three-marker panels (ER/Vim/CEA vs. ER/Vim/p16INK4) in distinguishing ECA from EMA. A tissue microarray was constructed using paraffin-embedded, formalin-fixed tissues from 35 hysterectomy specimens, including 14 ECA and 21 EMA. Utilizing the avidin–biotin technique, tissue array sections were immunostained with the four aforementioned individual markers (ER, Vim, CEA, and p16INK4). In addition to the four individual monoclonal antibodies, both their respective three-marker panels, proposed here, showed statistically significant (p < 0.05) frequency differences between these two gynecologic tumors (ECA vs. EMA). The panel performance and test effectiveness revealed that both three-marker panels are promising and very helpful. According to our data, when histomorphological and clinical doubt exists as to the primary site of origin, we recommend using either of these two conventional three-marker panels, which consist of ER/Vim/CEA and ER/Vim/p16INK4. CEA and p16INK4 can be interchanged with confidence without significantly influencing the panel presentations and efficiencies in distinguishing between adenocarcinomas of endocervical and endometrial origin.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Lurain JR, Bidus MA, Elkas JC (2007) Uterine cancer, cervical and vaginal cancer. In: Berek RS (ed) Novak’s gynecology, 14th edn. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (LWW), Philadelphia, pp 1343–1402

Schorge JO, Knowles LM, Lea JS (2004) Adenocarcinoma of the cervix. Curr Treat Options Oncol 5:119–127

McCluggage WG, Sumathi VP, McBride HA et al (2002) A panel of immunohistochemical stains, including carcinoembryonic antigen, vimentin, and estrogen receptor, aids the distinction between primary endometrial and endocervical adenocarcinomas. Int J Gynecol Pathol 21:11–15

Yao CC, Kok LF, Lee MY et al (2009) Ancillary p16(INK4a) adds no meaningful value to the performance of ER/PR/Vim/CEA panel in distinguishing between primary endocervical and endometrial adenocarcinomas in a tissue microarray study. Arch Gynecol Obstet 280:405–413

Han CP, Lee MY, Kok LF et al (2009) Adding the p16INK4a-marker to the traditional 3-marker (ER/Vim/CEA) panel engenders no supplemental benefit in distinguishing between primary endocervical and endometrial adenocarcinomas in a tissue microarray study. Int J Gynecol Pathol 28:489–496

McCluggage WG, Jenkins D (2003) p16 immunoreactivity may assist in the distinction between endometrial and endocervical adenocarcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol 22:231–235

Mittal K, Soslow R, McCluggage WG (2008) Application of immunohistochemistry to gynecologic pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Medicine 132:402–423

Walker RA (2006) Quantification of immunohistochemistry—issues concerning methods, utility and semiquantitative assessment I. Histopathology 49:406–410

Taylor CR, Levenson RM (2006) Quantification of immunohistochemistry—issues concerning methods, utility and semiquantitative assessment II. Histopathology 49:411–424

Remmele W, Schicketanz K-H (1993) Immunohistochemical determination of estrogen and progesterone receptor content in human breast cancer. Computer-assisted image analysis (QIC score) vs. subjective grading (IRS). Pathol Res Pract 189:862–866

Klein M, Vignaud JM, Hennequin V et al (2001) Increased expression of the vascular endothelial growth factor is a pejorative prognosis marker in papillary thyroid carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:656–658

Kamoi S, AlJuboury MI, Akin MR et al (2002) Immunohistochemical staining in the distinction between primary endometrial and endocervical adenocarcinomas: another viewpoint. Int J Gynecol Pathol 21:217–223

Matos LL, Stabenow E, Tavares MR et al (2006) Immunohistochemistry quantification by a digital computer-assisted method compared to semiquantitative analysis. Clinics 61:417–424

Zweig MH, Campbell G (1993) Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) plots: a fundamental evaluation tool in clinical medicine. Clin Chem 39:561–577

Metz CE (1978) Basic principles of ROC analysis. Semin Nucl Med 8:283–98

Kamoi S, AlJuboury MI, Akin MR et al (2002) Immunohistochemical staining in the distinction between primary endometrial and endocervical adenocarcinomas: another viewpoint. Int J Gynecol Pathol 21:217–223

Khoury T, Tan D, Wang J et al (2006) Inclusion of MUC1 (Ma695) in a panel of immunohistochemical markers is useful for distinguishing between endocervical and endometrial mucinous adenocarcinoma. BMC Clin Pathol 6:1

Reid-Nicholson M, Iyengar P, Hummer AJ et al (2006) Immunophenotypic diversity of endometrial adenocarcinomas: implications for differential diagnosis. Mod Pathol 19:1091–1100

Dabbs DJ, Sturtz K, Zaino RJ (1996) Distinguishing endometrial from endocervical adenocarcinoma. Hum Pathol 27:172–177

Castrillon DH, Lee KR, Nucci MR (2002) Distinction between endometrial and endocervical adenocarcinoma: an immunohistochemical study. Int J Gynecol Pathol 21:4–10

Alkushi A, Irving J, Hsu F et al (2003) Immunoprofile of cervical and endometrial adenocarcinomas using a tissue microarray. Virchows Arch 442:271–277

Han CP, Lee MY, Tzeng SL (2008) Nuclear receptor interaction protein (NRIP) expression assay using human tissue microarray and immunohistochemistry technology confirming nuclear localization. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 27:25

Han CP, Kok LF, Wang PW et al (2009) Scoring p16INK4a immunohistochemistry based on independent nucleic staining alone can sufficiently distinguish between endocervical and endometrial adenocarcinomas in a tissue microarray study. Mod Path 22:797–806

Bodner G, Schocke MF, Rachbauer F et al (2002) Differentiation of malignant and benign musculoskeletal tumors: combined color and power Doppler US and spectral wave analysis. Radiology 223:410–416

Young RH, Clement PB (2004) Pathology of endometrial carcinoma. In: Fuller AF, Seiden MV, Young RH, American Cancer Society (eds) Uterine cancer, 1st edn. PMPH, USA, pp 52–77

Young RH, Clement PB (2002) Endocervical adenocarcinoma and its variants: their morphology and differential diagnosis. Histopathology 41:185–207

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from Department of Health (DOH98-PAB-1001-E and DOH98-PAB-1009-I), Chung-Shan Medical University Hospital (CSH-97-A-09 and CSH-2009-B-007), Taiwan, ROC.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

C.-P. Han, M.-Y. Lee, and Y.-S. Tyan have equally contributed to this article.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Han, CP., Lee, MY., Tyan, YS. et al. p16INK4 and CEA can be mutually exchanged with confidence between both relevant three-marker panels (ER/Vim/CEA and ER/Vim/p16INK4) in distinguishing primary endometrial adenocarcinomas from endocervical adenocarcinomas in a tissue microarray study. Virchows Arch 455, 353–361 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-009-0826-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-009-0826-7