Abstract

Titin, the giant elastic ruler protein of striated muscle sarcomeres, contains a catalytic kinase domain related to a family of intrasterically regulated protein kinases. The most extensively studied member of this branch of the human kinome is the Ca2+–calmodulin (CaM)-regulated myosin light-chain kinases (MLCK). However, not all kinases of the MLCK branch are functional MLCKs, and about half lack a CaM binding site in their C-terminal autoinhibitory tail (AI). A unifying feature is their association with the cytoskeleton, mostly via actin and myosin filaments. Titin kinase, similar to its invertebrate analogue twitchin kinase and likely other “MLCKs”, is not Ca2+–calmodulin-activated. Recently, local protein unfolding of the C-terminal AI has emerged as a common mechanism in the activation of CaM kinases. Single-molecule data suggested that opening of the TK active site could also be achieved by mechanical unfolding of the AI. Mechanical modulation of catalytic activity might thus allow cytoskeletal signalling proteins to act as mechanosensors, creating feedback mechanisms between cytoskeletal tension and tension generation or cellular remodelling. Similar to other MLCK-like kinases like DRAK2 and DAPK1, TK is linked to protein turnover regulation via the autophagy/lysosomal system, suggesting the MLCK-like kinases have common functions beyond contraction regulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Many cellular processes, from cell differentiation and migration during development to functional organ adaptation postnatally, involve the sensing and processing of mechanical stress to trigger cellular responses. Many tissues change their physiological properties rapidly in response to altered mechanical load, including skin, bone, connective tissue, vessels, and smooth and striated muscles. These responses include cell proliferation (e.g. skin callus formation), apoptosis and resorption, or functional remodelling of pre-existent cells by hypertrophy or atrophy. In striated muscle, remodelling on the cellular level plays a major role in the adaptation to changes in workload (reviewed in [35, 108]) especially in the heart, where cell proliferation plays a negligible role in short-term adaptation [11]. Of clinical interest is the short-term adaptation of heart muscle to increased preload by the Frank Starling mechanism that modulates cardiac performance on a beat-to-beat basis, but cardiac growth and remodelling are also directly and indirectly mechanically controlled [24]. For such control mechanisms to act, the muscle cell must contain sensors responding to changes in mechanical load. While mechanosensors have been identified at the cell membrane, e.g. the integrin receptor signalling pathway [22, 29], increasing evidence points to a pivotal role of sensing mechanisms in the contractile machinery itself.

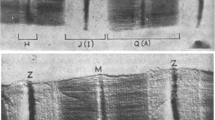

Striated muscle contractility depends on ordered arrays of myosin and actin filaments in repetitive units, the sarcomeres (reviewed in [30]). Sarcomeres have emerged not only to generate force and motion, but also to integrate a host of signalling functions in muscle mechanotransduction. Both the transverse anchoring planes of actin and myosin filaments—the Z-disk and M-band, respectively—have been implicated in active signalling processes relaying information on mechanical strain to cellular systems that control gene expression, protein synthesis, and protein degradation (reviewed in [35, 36, 50, 60, 69]). Recently, combinations of structural biology, biochemical and cell biological analysis, molecular dynamics simulations [38, 68], and single-molecule force spectroscopy [12, 96, 125] have led to fundamental mechanistic insights into the function of some mechanosignalling complexes at the Z-disk and M-band anchoring planes.

Upon development of active force by myosin motors pulling on actin filaments, substantial mechanical stress acts on the various structures of the sarcomere, which needs to be counteracted by the cross-links of the actin and myosin filaments themselves. Electron microscopic analysis of isometrically contracting skeletal muscle fibres revealed that the resistance of Z-disks and M-bands to mechanical strain differ markedly: While Z-disks showed no appreciable deformation along the sarcomere axis, the M-bands buckled rapidly [49] up to the point of rupture. This selective buckling of the M-band is likely a result of the shear forces between adjacent myosin filaments and is on the order of 10 nm or more [1, 52]. At the same time, the myosin interfilament spacing does not change significantly under isometric contraction, suggesting that most contraction-induced changes seem to result in axial M-band strain and displacement of myosin [31]. This is contrary to the Z-disk, where active contraction results predominantly in changes in lattice spacing (reviewed in [36]).

The integration of actin and myosin filaments at the M-band and Z-disk, and thus also the length of the sarcomere, are determined by the giant sarcomeric protein titin [126] (also known as connectin [75]). Titin is a highly modular, over 1-μm long protein composed mostly of immunoglobulin (Ig) and fibronectin-like (Fn) domains and elastic linker regions [63]. Titin combines multiple functions: a molecular ruler for sarcomere assembly, the main source of passive elasticity in the sarcomere, and a hub for signal transduction [35, 69, 123]. Apart from the hundreds of Ig and Fn domains, many of which interact with sarcomeric ligands (reviewed in [60, 61, 66]), and the elastic regions in the I-band [63], titin contains a single catalytic kinase domain (TK) near its C-terminal, M-band-associated end [64]. The TK domain is located at the M-band periphery, about 50 nm from the central M-band line M1 [86] and is superficially similar to the catalytic domains of other kinases of the myosin light-chain kinase (MLCK) branch (Fig. 1) of the human kinome [37, 64, 70], as well as the kinase domains of the related giant muscle proteins twitchin (TwK) from Caenorhabditis elegans [9] and projectin from Drosophila melanogaster [10]. Generally, MLCK-like kinases are considered to be autoinhibited serine/threonine kinases, where the major mechanism of activation is the relief of autoinhibition by the binding of Ca2+–calmodulin (CaM) to the C-terminal autoinhibitory region, thus removing the sterical blockage of the active site without requirement of phosphorylation of sites in the activation loop, as in phosphorylation-regulated protein kinases. MLCK1 to 3 are expressed in smooth, skeletal and cardiac muscle, respectively, while MLCK4 (MYLK4) seems ubiquitously expressed; its role as a myosin light-chain kinase is not experimentally verified. The classical MLCKs phosphorylate the N-terminus of myosin regulatory light chain to initiate or modulate myosin contractility [56]. MLCKs are thus involved in myosin-linked processes as diverse as cell migration, cytoskeletal remodelling, vessel tone control, peristaltic movement or fine-tuning of striated muscle contractility.

The MLCK branch of the human kinome (adapted from [70]). The CaM kinase family contains a group of related protein kinases that includes obscurin kinases 1 and 2 (OBSCN-1 and OBSCN-2), striated muscle preferentially expressed protein kinases 1 and 2 (SPEG-1 and SPEG-2), titin (TTN), trio and kalirin (KALRN), the myosin light-chain kinases of smooth muscle (MYLK1), skeletal muscle (MYLK2), cardiac muscle (MYLK3) and the more ubiquitously expressed MYLK4. Death-associated protein kinases 1–3 (DAPK1–3) and the death-associated protein kinase-related apoptosis-inducing protein kinase 1 and 2 (DRAK1 and DRAK2) form a separate sub-branch. Kinases that are unlikely to be CaM-regulated are shown in red

However, as we shall see, there are crucial differences in the TK structure and regulation mechanism that may lead to new perspectives also on other members of the MLCK branch of the human kinome.

An unusual active site: implications for regulation and activity of titin kinase

The crystal structure of titin kinase [78] revealed the complex autoinhibited conformation of TK. The C-terminal autoinhibitory tail (AI) is formed from three secondary structure elements, αR1, αR2 and βR1, wrapping around the catalytic domain and tightly occluding the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) binding site. This autoinhibited conformation is overall highly similar to the invertebrate TwK [51, 58], but also to the autoinhibited conformation of classical CaM-regulated kinases like CaMKIIδ [103] or death-associated protein kinase 1 (DAPK1, [23]) (Fig. 2).

Structures of C-terminally autoinhibited protein kinases. Despite sequence identity of only about 40% and global overall structural similarity within the protein family, the titin and twitchin kinase domains show unique structural homology of their AI. In both kinases, the C-terminal autoinhibitory tail αR2 helix (bright red) tightly occludes the ATP binding cleft, while the αR1 helix (dark red in all kinases shown) does not directly block the catalytic cleft and shows a conserved topology. The function of the more C-terminal part of the autoinhibitory tail (bright red) is that of the actual autoinhibitor (in some cases like CaMKIIδ as a pseudosubstrate) despite very different secondary structure. In the case of CaMKIIδ and CaMKI, this segment contains the CaM binding site. Titin and twitchin share the unusual antiparallel β-sheet between the βR1 strand at the very C-terminus of the autoinhibitory tail and the activation segment βC10 strand. The complete autoinhibited structure of DAPK1 is not yet available; the published structure shows a similar αR1 helix topology as the other CaM kinase-like kinases; the CaM binding site is again in the—missing—C-terminal part of the autoinhibitory tail. Activation segments are shown in orange, the catalytic aspartate side chain in red. There are unresolved gaps in the CaMKI structure including a larger part of the activation segment. The following PDB entries are shown: nematode twitchin, 1KOA; human titin, 1TKI; human CaMKIIδ, 2VN9; human CaMKI, 2JC6; human DAPK1, A2A2

However, although the short amphipathic helix αR1 binds weakly to CaM as an isolated peptide [37], TK as well as the twitchin kinase domains from both Caenorhabditis and Aplysia fail to be activated by CaM [37, 45, 46, 58, 78], and CaM binding to the TK holoenzyme could only be detected using chemical cross-linking but not by size exclusion chromatography [37], unlike the stable CaM–DAPK complex [23]. Similarly, the projectin kinase domain from Locusta migratoria is insensitive to CaM [130]. Recent structural progress allows to compare the topology of the AI regions of these kinases: the ATP binding site in the canonical CaM-regulated kinases is blocked by a peptide segment which also forms the Ca2+–calmodulin binding site, in a region topologically equivalent to αR2 in TK and TwK (Fig. 2). Ca2+–calmodulin binding to TK AI peptides (and the amphipathic helix binding Ca2+–S100A1 in twitchin) resides further N-terminal, in αR1. These observations suggested that αR1, despite binding to CaM as an isolated peptide in a manner similar to but weaker than genuine CaM binding sites [4], has neither the right overall topology nor affinity for primary CaM regulation. TK and TwK are thus so far unique among the MLCK-like kinases in that CaM is not a primary activator of kinase activity.

Twitchin kinase could, however, be activated in vitro by the dimeric calcium-binding protein S100A1 in the presence of Ca2+ and low concentrations of Zn2+ [45]; this could not be confirmed for titin kinase [78]. As the C. elegans genome does not contain an S100 gene, the physiological significance of S100 activation of giant muscle protein kinases remains unclear. Although a yet unidentified protein activator cannot be excluded, TwK and TK thus seem to share a non-canonical C-terminal autoinhibition mechanism that is primarily insensitive to Ca2+–calmodulin, despite possibly divergent physiological functions and further differences in the structure of their active sites.

Additionally, in the C-terminal AI, several titin-specific amino acids in the active site of TK lead to an unusual autoinhibited conformation. All active protein kinases contain a completely conserved aspartate residue in the catalysis loop, which acts as a catalytic base during the phosphotransfer reaction (reviewed e.g., in [41, 122]). The catalytic base in mammalian titin, D127 (nomenclature based on the structure of TK, 1TKI [78]) is blocked by Y170, whose hydroxyl group is poised towards the catalytic base similar to the autoinhibitory tyrosine in phosphorylation-regulated tyrosine kinases like Src [78] (Fig. 3a–c). Apart from suggesting a tyrosine–phosphorylation step in the activation, one speculative implication could be that TK might also have tyrosine kinase activity and act as a dual-specificity kinase, but there is no experimental evidence for this. A similar pseudosubstrate inhibition is observed in the CaM kinase family in CaMKIIδ by T287 (Fig. 2) [103]. This residue, however, resides in the AI close to the CaM binding site, whereas Y170 in TK lies in the extended activation segment [78] (Fig. 3c). In TK, Y170 is coordinated by a salt bridge and hydrogen bond network with D127 that also involves R129. The equivalent positions in other S/T kinases like cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA, D166 and K168) or CaMKIIδ (D136 and K138), form essential salt bridge and hydrogen bond connections to the ATP γ-phosphate, with D166/136 serving as a catalytic base that facilitates the dissociation of the substrate hydroxyl and thus promoting the nucleophilic attack on the γ-phosphate moiety [115, 124]. While a lysine at the +2 position from the catalytic base is a feature conserved in all CaMK-like kinases (except for obscurin kinase 2, [32]) and almost all S/T kinases, the unusual R129 in TK is highly conserved among chordates. Possible exceptions are avian TKs, where available sequences show a lysine at position 129 (Fig. 4). In the structurally and kinetically well-investigated S/T kinases like phosphorylase kinase and PKA, interactions of the equivalent lysine (K151 and K168, respectively) with the ATP γ-phosphate likely stabilise the transition and product states [115, 124]. An arginine residue at this position with its higher pKa could thus be expected to lead to a low catalysis rate due to slow product release. The equivalent position in all tyrosine kinases, however, is also an arginine (Fig. 4). The enzymatic characterisation of avian TK might therefore be insightful. The interplay between the two autoinhibitory motifs, the C-terminal AI and Y170, is complex and may involve also long-range conformational changes: an extensive hydrogen bond network links the catalytic aspartate, tyrosines Y170 and Y169 to Y281 in the αR1 helix (Fig. 3d), suggesting that conformational changes in the Y170 loop could feed back on conformational changes in the AI, and vice versa. The position of Y170 suggests that phosphorylation of this residue could lead to full activation of TK once the autoinhibitory tail was removed. Although a tyrosine kinase activity phosphorylating recombinant TK was detectable in early differentiating cultured myoblasts [78], the identity and physiological significance of this kinase has remained enigmatic. Weak CaM modulation of TK activity is detectable only when phosphorylation of the autoinhibitory tyrosine is mimicked by replacement with glutamate, which renders the enzyme part constitutively active [78]. There is no indication so far that tyrosine phosphorylation of TK is activated by CaM. However, the low degree of CaM-stimulated activity in very pure preparations of Y170E mutant TK (at most tenfold, our unpublished observations) suggests that CaM regulation of TK, even in the tyrosine-phosphorylated state, is not likely to play a major regulatory role.

Structure of titin kinase and motifs involved in autoinhibition and catalysis. a Overall topology of TK, with the C-terminal autoinhibitory tail (hues of red) blocking access to the active site between the large and small lobes. The active site is blocked by αR2 (bright red). Side chains of key residues discussed are shown. The activation segment is shown in orange. b View towards the ATP binding cleft shows how αR2 (bright red) blocks ATP binding. K36, a key residue for coordinating the α/β-phosphates of ATP is shown as well as E51 in αC1. These two residues often form a salt bridge in active kinases but are separated by more than 4 Å in autoinhibited TK. c The catalysis loop around the catalytic base D127 shows the salt bridge and hydrogen bond network (green lines) between D127, R129, Q150 and the autoinhibitory Y170. d The tyrosine hydrogen bond network between the catalytic base D127, connecting Y170 and Y169 in the extended activation segment with αR1 in the autoinhibitory tail (dark red). Based on the crystal structure of TK, PDB entry 1TKI

a The catalysis loop and activation segment of titin kinase across the chordate classes. Key residues are highlighted in yellow, and residues identical to human titin are shown in capital letters. Note that the known avian titins show the lysine residue at position 129 that is canonical in other S/T kinases, where an arginine is conserved in all higher chordate titins down to lancelet. Note that sequence coverage makes the assessment of some amino acid exchanges in the lower species difficult. Available sequences suggest that the second kinase in the lancelet (Branchiostoma floridae) giant muscle protein (XP_002597967) is inactive, as the catalytic aspartate 127 (red) is exchanged for histidine. Numbering based on the TK crystal structure. b Catalysis loop and activation segments of exemplary human tyrosine and serine–threonine kinases and pseudokinases. Residues crucial for catalytic activity are highlighted in yellow, the catalytic aspartate is marked in red. Note the arginine residue at +2/4 from the catalytic aspartate instead of lysine in tyrosine kinases, a constellation found in TK and the obscurin kinase-2 domain. The boxed asparagine and acidic residues at D + 5 and in the DFG motif at the beginning of the activation segment are involved in coordinating the Mg2+ of Mg-ATP [120]. CASK, also sometimes classified as a pseudokinase [14], shows Mg2+-independent activity due to several mutations in the Mg2+-coordinating residues [81]. On this basis, the presumed pseudokinase STK40 might also show unusual catalytic activity like other pseudokinases [121]. ULK4, STRAD4 [102] and ILK [133], however, all lack crucial residues for catalysis, notably the catalytic aspartate for STRAD and ILK, and are inactive. Acronyms not mentioned in Fig. 1. IRK, insulin receptor kinase; SRC-K, Src kinase; PKA, cAMP-dependent protein kinase; CASK CaM-activated serine–threonine kinase [81]; STK40 serine–threonine kinase 40; ULK4, unc-51-like kinase 4; STRAD, STE20-related kinase adapter protein beta; ILK, integrin receptor-linked kinase

The other unusual exchange in TK is the replacement of the aspartate in the conserved DFG motif at the beginning of the activation segment with glutamate, E147 (Figs. 3a and 4). Lastly, closer inspection of the active site reveals a further configuration suggestive of an inactive conformation of autoinhibited TK. E51 of the αC1 helix is a completely conserved residue engaged with K36 in a salt bridge in active kinases [100]. In autoinhibited TK, these residues are separated beyond salt bridge distance by 4.91 Å (Fig. 3b), as opposed to, e.g. DAPK with 2.68 Å. However, whether this is supportive of an inactive conformation requiring further allosteric activation by αC1 helix movement is debatable, as the corresponding residues in the active, CaM-bound complexes of DAPK or CaMKIIδ are also separated by more than 4 Å (4.51 and 4.74 Å, respectively). Overall, the structure of the autoinhibited TK suggests that the catalytic site has accommodated these exchanges, and adopts a conformation consistent with an active kinase rather than a pseudokinase [14], as is also highlighted by the conservation of other crucial residues involved in catalysis (Fig. 4b). Indeed, cellular responses to TK discussed below require the presence of D127 [65].

A mechanically modulated activation mechanism?

The CaM-insensitive autoinhibited state of TK raises the question how an open state, capable of binding ATP and peptide substrates or potential scaffold proteins, could be achieved. For access of the autoinhibitory tyrosine, the C-terminal autoinhibitory tail needs to be partly removed, with no protein factor identified so far being able to do so. Relieving intramolecular autoinhibition can be regarded as a partial unfolding event of the autoinhibited conformation of the kinase. The folded and closed, and partially unfolded open states are separated by an energy barrier that can be overcome by ligand binding, e.g. CaM in the classical CaM kinases or phosphorylation. For a protein that is firmly integrated into the cytoskeleton and the contractile machinery and thus exposed to force, the conformational space is not only governed by thermal energy or ligand interactions, but also by the anisotropic effects of mechanical force [26]. Could enzymatic functions in titin, whose elastic functions in the I-band are paradigmatic for force-induced conformational changes by reversible protein unfolding [104], also be modulated by mechanically induced conformational changes?

The C-terminus of titin is embedded into the M-band via interactions in a ternary complex with myomesin, the giant GTPase regulator and protein kinase obscurin [105, 139] and its small structural homologue obscurin-like 1 [33, 93]. The M-band, being much more compliant than the Z-disk [3, 49], is ideally placed as a strain sensor [1, 2]. As the M-band lattice is deformed only during active contraction due to the shear forces between adjacent myosin filaments, it is optimally placed for detecting the actual workload on the myofibril [1]. Force-probe molecular dynamics simulations were thus used to test the hypothesis that conformational changes consistent with kinase activation could be induced mechanically in TK. Indeed, these simulations suggested that this could be the case and that forces acting at low velocities can lead to the sequential unfolding of the autoinhibitory tail, thus opening the active site while preserving the catalytic core [38]. Experimental verification of these simulations, which were performed at pulling rates of between 0.4 to 5 m/s due to computational restraints, were performed using single-molecule atomic force spectroscopy at the much slower pulling rate of 0.72 μm/s. This experimental probing of the mechanical properties of TK confirmed that relief of autoinhibition is possible by partial unfolding of the C-terminal autoinhibitory domain by “gating” forces around 30 pN and displacements around 10 nm [97]. Analysis of the force spectroscopy data and molecular dynamics simulations suggested that the open conformation is able to bind ATP, and to promote further steps in TK activation, by exposing the autoinhibitory Y170 for auto- or trans-phosphorylation. The experimentally determined forces of 30 pN at physiological temperature compare to the force generated by about five to six myosin motor domains (assuming a force of 6 pN each [94]), the myosin heads within one “crown” of the myosin filament. In the A-band, these crowns of 3 × 2 myosin heads are arranged every 14.3 nm on either side of the M-band. Therefore, a displacement of a myosin filament by just one 14.3 nm myosin repeat with respect to the Z-disks will lead to a theoretical maximal force imbalance of (3 × 2 × 2) × 6 pN or 72 pN. The measured gating force of 30 pN, and the gating distance of 9 nm for opening the TK active site are therefore within the predicted range of shear forces arising physiologically between myosin filaments.

Interestingly, local protein unfolding and refolding is emerging as a common mechanism in the activation of C-terminally autoinhibited kinases (Fig. 5). In the CaM-regulated CaMKIIδ, the entire autoinhibitory tail undergoes substantial unfolding with partial refolding of the CaM binding region in the complex with calmodulin [103]. The autoinhibited form of the MLCK-like DAPK is not yet available, but its CaM-bound structure [23] suggests that similar major structural rearrangements and partial AI unfolding must occur during activation. These combined results suggest that TK—and possibly TwK—could indeed function as a force sensor by switching between a closed and open conformation by mechanically, rather than ligand-induced partial unfolding of its autoinhibitory tail.

Links to the protein turnover machinery

Protein kinases propagate signals either by the direct phosphorylation of one or many downstream substrates or by interacting with further scaffold proteins and/or other protein kinases in more complex signalosomes, where elements involved in signal propagation and regulation conjoin. In a search for ligands interacting with the open, but not the autoinhibited closed form of TK, a signalling complex of two structurally related ubiquitin-associated zinc-finger proteins, nbr1 and p62/SQSTM1 was identified, where nbr1 forms the primary interaction with the open TK [65]. A muscle-specific family of closely related ubiquitin E3 ligases, MURF1, MURF2 and MURF3, in turn interact with p62/SQSTM1 (Fig. 6). In the absence of mechanical activity in pharmacologically arrested cardiomyocytes, this signalosome dissociates, and p62/SQSTM1 translocates to the intercalated disk and around the nucleus, while MURF2 translocates to the nucleus, where it can then interact with nuclear partners like SRF [65]. SRF interaction was also reported for MURF1 [134] and MURF3 [116]. Nuclear MURF2 leads to down-regulation of nuclear SRF and its cytoplasmic relocalisation, thus suppressing SRF-dependent muscle gene expression [65]. Nuclear MURF2 translocation was also observed in denervated skeletal muscle [65] and recently in an animal model of critical illness myopathy, where MURF1 and MURF2 were observed to translocate together with p62/SQSTM1 to the nucleus, followed later by the cytoplasmic accumulation of MURFs, p62 and SRF [87]. These observations suggest that MURFs can act as transcriptional repressors in both mechanically inactive cardiac and skeletal muscle cells. The interaction of MURF2 with SRF, and also the as yet uncharacterized interaction of MURF1 with the transcriptional cofactor, glucocorticoid modulatory element binding protein-1 (GMEB-1) [79] thus suggest important atrophy-related nuclear functions of MURFs, possibly by ubiquitination of nuclear targets (reviewed in [35]). In addition, MURFs regulate the turnover of multiple structural and metabolic proteins during muscle atrophy and remodelling (reviewed in [82, 135]).

Local protein unfolding and refolding in the activation of protein kinases. a The genuinely CaM-activated CaMKIIδ is autoinhibited by the C-terminal autoinhibitory tail (hues of red) that blocks predominantly the catalytic base via an unstructured segment bearing the autoinhibitory threonine 287 (side chain shown in red). The activation segment (orange) is in an open configuration, similar to titin. Upon binding of CaM, the C-terminal autoinhibitory tail (hues of red) undergoes major unfolding–refolding events: the main inhibitory region around T287 (AI, bright red) adopts a helical conformation in complex with CaM, whereas the previously helical region around αR1 (dark red) unfolds and opens up further regulatory threonine phosphorylation sites [103]. b In titin kinase, external force (F) can lead to the activation-related unfolding of the autoinhibitory tail, with the main autoinhibitory αR2 (bright red) being pulled out of the ATP binding site and thus exposing D127 (red) and Y170 (orange). The αR1 helix (dark red) remains structured but eventually also unfolds; whether it undergoes conformational changes upon nbr1 binding is currently unknown. Open structures based on the low-velocity force-probe molecular dynamics simulations in [38], and the CaMKIId -CaM complex [103], PDB 2WEL. The unresolved segment in the CaMKIIδ AI structure has been extrapolated as a dashed red line. Autoinhibited structures as in Fig. 2.

Known interactions of the titin kinase associated, ubiquitin- and LC3-binding proteins Nbr1 and SQSTM1/p62. Both Nbr1 and SQSTM1 bind polyubiquitin chains via their C-terminal UBA domain and to the autophagy membrane component Atg8/LC3. Further links to small protein modifiers exist via the MURFs to SUMO [21, 79, 95]. Nbr1 and SQSTM1 interact with several other protein kinases including the atypical protein kinase-Cζp38 MAP kinase and several signalling adaptors, many of which are relevant for the control of muscle growth and remodelling

This signalling complex reveals links to the regulation of muscle protein turnover not only by the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway (Fig. 6) and is tightly regulated during development [92]. P62/SQSTM1 is emerging as a central adaptor molecule involved in several pathways relevant in myogenic differentiation and stress response. P62/SQSTM1 interactions include MAP kinase p38 [117], the MAP kinase kinase MEK5 [25] as well as its upstream MAPK kinase kinase, MEKK3 [84] that are involved in ERK5 activation. Further interactions involve the TNF receptor-associated kinase RIP [109], atypical protein kinases-C (aPKC [98]), Src family tyrosine protein kinases like lck [55, 91], and insulin receptor/insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor signalling via Grb14 [17, 47]. P62/SQSTM1 links input from a number of these kinases to the activation of NFκB [84, 109, 110, 117, 136]. Some of these have multiple roles in cell survival and myogenic differentiation. For example, p38 activates the myogenic transcription factors MEF2 and MyoD by phosphorylation of MEF2C [99, 141], and the MEK5/ERK5 kinase cascade is crucially involved in myogenic differentiation and hypertrophic growth via MEF2 activation [8, 27, 85, 127]. P62/SQSTM1 also interacts with, and regulates the orphan hormone receptor COUP-TFII [72], which has been implicated in strain adaptation of cardiac gene expression and metabolic adaptation in skeletal muscle [20, 83, 106].

P62/SQSTM1 can also target ligands of its PB1 and ZZ domain region to polyubiquitin chains via its C-terminal ubiquitin-associated UBA domain. This may assemble larger signalosomes via lysine-63 linked polyubiquitin, in analogy to other ubiquitin-mediated kinase signalling pathways [40, 118]. Association with lysine-48 linked polyubiquitin chains, however, could target these complexes for proteasomal degradation [112] and, via the interaction of p62 with LC3, to the autophagy of ubiquitinated proteins [90]. Nbr1 has recently emerged to be similarly implicated in autophagic protein turnover by recruiting polyubiquitinated proteins and binding to the autophagosomal membrane anchor LC3 [57, 128]. Similar to p62/SQSTM1, however, nbr1 also emerges as a scaffold for multiple protein kinase signalling pathways including PKCζ and p38 MAP kinase (Fig. 6) [131, 132], hinting at important generic and partly overlapping roles of theses adaptor proteins in cell signalling as well as protein turnover regulation.

Autophagy is increasingly recognised as a crucial protein degradation mechanism in muscle in addition to the ubiquitin–proteasome system [108], but is also emerging as a novel mechanism in regulating cellular signal transduction by removing activated signalling proteins [6, 54]. It is interesting to speculate whether the main role of nbr1 in TK signalling is in signal propagation or attenuation, a question that can only be answered by analysing appropriate knockout models. There may also be significant redundancy between p62/SQSTM1 and nbr1 due to the overlapping ligand spectrum. This may explain, for example, why p62 knockout animals do not seem to show an overt muscle phenotype [28, 59, 88] despite the involvement of p62/SQSTM1 in muscle autophagy [76], and why a truncated nbr1 mouse model (leaving the titin- and p62-binding PB1 domain region intact) shows a bone [132], but not muscle phenotype (MG and C. Whitehouse, unpublished observations).

The vital importance of TK in maintaining the turnover of muscle proteins in human via nbr1 and p62/SQSTM1 is highlighted by a point mutation in the αR1 helix, R279W, in the human kinase domain that abrogates nbr1 binding. This leads to a myopathy with failure of load-dependent protein turnover (human myopathy with early respiratory failure, HMERF) with the aberrant localisation, aggregation of p62/SQSTM1 and possibly vesicular accumulation of nbr and nuclear translocation of MURF [65]. These observations suggest that TK acts as a strain-modulated sarcomeric “receptor” for proteins involved in cellular remodelling and thus contributes to the control of mechanical load-dependent remodelling of muscle. Interestingly, HMERF can also be caused by mutations in other proteins than titin kinase [119], and the identification of these additional disease loci should prove highly insightful for unravelling the disease mechanism and might also answer why in TK-associated HMERF, cardiac muscle appears to be spared in early disease.

It will be interesting to see whether strain activation of TK occurs continually to regulate sarcomere homeostasis and remodelling or only to sense and repair local mechanical damage. This remains to be tested and will require the combined use of animal models with biochemical and biophysical methods.

Substrates and scaffolds

Little is known about other physiological ligands and substrates of TK. The first in vitro substrate identified in developing myoblasts was the small, muscle-specific Z-disk protein telethonin (also known as TCAP), where constitutively active TK phosphorylates S157 in the C-terminus [78]. As constitutively active TK disrupts myofibril formation in cultured myoblasts, it was suggested that TK-mediated telethonin regulation might play an important role in the control of ordered sarcomere assembly [78]. However, a titin M-band deletion mouse model, where a larger part of the M-band including the TK domain was deleted, can form myofibrils even though these quickly become unstable [129]. Although the ultimate disassembly of titin M-band-deficient sarcomeres would agree with the impaired communication to the protein turnover machinery via nbr1/SQSTM1/MURF, all of which are expressed in the heart from the earliest detectable stages onwards [92], the role of telethonin phosphorylation remains utterly enigmatic—as does, in fact, the protein overall. Although telethonin is a Z-disk protein, it interacts with a host of proteins including secreted growth factors (reviewed in [66]), and has also been observed at the M-band [142], similar to other Z-disk proteins like myotilin [18]. Analysis of telethonin phosphorylation may be confounded by the observation that TK is not the only kinase, which, at least in vitro, can phosphorylate the C-terminus telethonin, as telethonin interacts also with protein kinase D [43] and is a substrate of this kinase of the CaM kinase branch. Redundant kinase pathways might therefore complicate the phenotype of PKD or TK knockout animals.

Point mutations inactivating the telethonin phosphorylation sites or short-term knockdown impair myofibril formation or maintenance in Xenopus [107]; in human, deletion of the C-terminal portion of telethonin [80] or mutations close to the TK phosphorylation site (R153H, [44]) cause hereditary limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (LGMD2G) or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. This suggests an important yet uncharacterised function of the telethonin C-terminus in muscle maintenance. Surprisingly, a knockout mouse for telethonin shows only a mild, late onset myopathic phenotype with apparently normal myofibrils [74], despite the function of telethonin as a major cross-linker of titin filaments at the Z-disk [12, 142]. However, telethonin localisation is clearly sensitive to mechanical load, with the protein being a sensitive marker of neurogenic atrophy [111] and its mRNA being rapidly down-regulated under denervation atrophy [77]. Understanding the physiological role of telethonin and its phosphorylation in load-dependent muscle remodelling will now likely require new approaches.

Both nbr1 and p62/SQSTM1 are in vitro substrates for TK [65], but as phosphorylation with recombinant titin kinase requires either mutagenesis on Y170 or C-terminal truncation, both of which may compromise catalytic activity or enzyme stability, the full impact and enzymatics of TK for these interacting proteins may be difficult to assess in vitro and may again require the use of more physiological settings. As both proteins also interact with many other signalling proteins and kinases [35, 73, 92, 131, 132], a scaffold function for the spatial integration of multiple signalling components is plausible, that could play a role in either signal propagation or attenuation (Fig. 6). In neonatal cardiomyocytes, the unloading-induced repression of SRF-dependent gene expression could be relieved by transfected constitutively active titin kinase [65], but not by a catalytically inactive D127A mutant, which also led to the reduction of cellular MURF. In this context, TK therefore acts as a brake on atrophic pathways, of which MURFs are one component. The exact mechanism of load-dependent muscle remodelling may again require a multidisciplinary approach to unravel completely.

The uneasy family relationships of the cytoskeletal “MLCK” kinases

The implications from our current understanding of titin kinase signalling are that the MLCK branch of kinases is neither only involved in myosin regulation, nor is it universally Ca2+–calmodulin-regulated. In fact, a comparison of their C-terminal autoinhibitory tails suggests that about half of these kinases do not show recognisable amphipathic segments with suitable topology relative to the catalytic core (Fig. 7) and are likely to be regulated by different ligands or altogether different mechanisms. Some MLCK-like kinases with genuine light-chain kinase activity like cardiac MLCK (MYLK3), have also been reported not to be regulated by Ca2+/calmodulin in vitro [19], despite a completely canonical CaM binding site (Fig. 7), and additional factors modulating calmodulin sensitivity like phosphorylation of the AI, similar to, e.g. CaMKIIδ, may be involved. Clearly, a rigorous biochemical analysis of this kinase family is required.

Sequence comparison of the autoinhibitory tails of the MLCK-like kinase branch. The CaM binding site in the skeletal MLCK M13 peptide [53, 89] and in confirmed and predicted CaM-regulated kinases are boxed in red; CaM kinase-I (CaMKI) is shown for comparison. About half of the MLCK-like kinases do not show a basic amphipathic region or a sufficiently long autoinhibitory tail and are thus possibly regulated by different mechanisms than CaM binding. The αR1 helix in titin and nematode twitchin are marked in magenta; αR2 (which blocks the ATP binding site) and βR1 are shown in red and blue, respectively. The synthetic titin peptide adopting helical conformation upon CaM binding [4], and the S100 binding peptide in twitchin [45] are underlined. Abbreviations as in Fig. 1.

Furthermore, it is now emerging that many MLCK-like kinases are not actual myosin light-chain kinases, but are involved in other regulatory processes: DAPK1 phosphorylates Beclin-1, a key protein involved in the initiation of autophagy, and is now recognised to regulate cell survival via the autophagy pathway [13, 140]. Similarly, “death-associated protein kinase-related apoptosis-inducing protein kinase 2” (DRAK2) phosphorylates p70S6 kinase [71] and is thus involved in metabolic flow regulation and, via the AKT-mTOR pathway, eventually also in the regulation of protein turnover [108]. The full scope of regulators and downstream ligands for most other MLCK-like kinases is yet to emerge, but it is noteworthy that three of them are now linked to autophagy and protein turnover regulation.

However, a unifying feature that is emerging is the apparently universal association of MLCK-like kinases with the cytoskeleton (Fig. 8). Apart from titin and obscurin, whose cytoskeletal integration is obvious and which, in the case of titin, combines the function of an elastic link between actin and myosin filaments with kinase signalling, similar linker functions emerge for other kinases. Non-muscle MLCK is firmly attached to actin and myosin filaments via an N-terminal nebulin-like actin-binding motif and the C-terminal myosin-binding telokin Ig domain [42, 48, 62, 114, 137, 138], and it could be interesting to investigate whether MLCK activity might therefore, in addition to the well-established CaM regulation, be subject to mechanical modulation that might contribute to stretch-induced MLCK activity [7, 67].

Domain pattern and interactions of the MLCK-like kinases. This kinase family is highly modular, combining catalytic kinase domains with various cytoskeleton-associated domains of the intracellular immunoglobulin and fibronectin family, as well as spectrin and ankyrin repeat domains. Most, if not all, MLCK-like kinases are cytoskeleton-associated via interactions with components of the actin or myosin filaments (red). The exact topology of the actin and myosin binding sites in invertebrate twitchin has not yet been established (red italics). Titin as well as three genuine MLCKs contain an entropic spring sequence, the PEVK sequence (after the predominant amino acids: proline, glutamate, valine and lysine [63]), which forms an elastic connection between the N-terminal actin and C-terminal myosin associated regions. Obscurin, kalirin and trio are unique in that they combine cytoskeleton-associated Rho-GDP/GTP exchange factor domains with protein kinase domains. The presence of two tandem kinase domains in SPEG and obscurin seems specific for striated muscle proteins, but their function is unknown. The domain patterns of the giant titin, twitchin and obscurin proteins is shown only partially around the signalling domains and schematically around the PEVK segment for titin

Similarly, molluscan twitchin kinase is tightly attached to both actin and myosin filaments and seems to be stretch-activated, thereby possibly contributing to the phosphorylation-mediated maintenance of the catch state in response to stretch [5, 15, 16, 34]. Indeed, the simulated unfolding of C. elegans twitchin kinase and initial force spectroscopy data, showed similar patterns as for TK [38, 39]. The cytoskeletal association for other MLCK-like kinases is less well investigated, but it seems clear that TRIO and Kalirin are actin-associated [101, 113]. A better understanding of the molecular interactions and knowledge of the full scope of substrates will provide a significant advance in understanding these kinases at the crossroads of cellular mechanics and signalling, which might be better called cytoskeletal kinases.

Conclusions and perspectives

Over recent years, the notion that the sarcomere is purely a contractile machine of high order has been challenged by the discovery that multiple signalling pathways not only affect the assembly or function of this structure, but that the sarcomere is a source of active communication controlling muscle cell proliferation, growth, and remodelling. The kinase domain of the giant elastic protein titin highlights that classification by sequence similarity may not always come to the bottom of the functional complexity of the human kinome. Its analysis has suggested that kinase signalling and mechanosensing may be more tightly interwoven than previously assumed, with the opening of the TK active site being directly mechanically triggered. Important insight has also been gained from studies in C. elegans, underscoring the value of this model organism. The observation that TK itself and many of its interactors are targets of hereditary muscle diseases not only highlights their importance, but raises the hope that a detailed understanding of their functions may result in new therapeutic approaches to ameliorate certain acquired and hereditary muscle diseases. The involvement of TK and its ligands in load-dependent muscle turnover should now be studied in more clinically relevant models like left ventricular load-dependent remodelling or in skeletal muscle disuse atrophy. Although titin is abundant, kinases are well drugable targets, and the TK signalling pathway might offer new perspectives for targeting muscle atrophy or cardiac hypertrophy. However, to what extent it is the scaffolding function rather than the actual catalytic activity of titin kinase that plays a dominant role in its crucial biological function remains to be elucidated. In the future therefore, integrating atomic structures and molecular modelling with cellular and single-molecule AFM data will be required not only to address the mechanosignalling functions of titin and its disruptions in muscle disease, but also to understand related functions in other cytoskeletal systems. The direct mechanical activation of ATP binding by titin kinase may prove a paradigm for other cytoskeletal signalling domains, especially the kinases of the cytoskeletal MLCK-like family in vertebrates and invertebrates, whose tight cytoskeletal association makes such a regulation plausible.

References

Agarkova I, Perriard JC (2005) The M-band: an elastic web that crosslinks thick filaments in the center of the sarcomere. Trends Cell Biol 15:477–85

Agarkova I, Ehler E, Lange S, Schoenauer R, Perriard JC (2003) M-band: a safeguard for sarcomere stability? J Muscle Res Cell Motil 24:191–203

Akiyama N, Ohnuki Y, Kunioka Y, Saeki Y, Yamada T (2006) Transverse stiffness of myofibrils of skeletal and cardiac muscles studied by atomic force microscopy. J Physiol Sci 56:145–151

Amodeo P, Castiglione Morelli MA, Strazzullo G, Fucile P, Gautel M, Motta A (2001) Kinase recognition by calmodulin: modeling the interaction with the autoinhibitory region of human cardiac titin kinase. J Mol Biol 306:81–95

Avrova SV, Shelud'ko NS, Borovikov YS, Galler S (2009) Twitchin of mollusc smooth muscles can induce “catch”-like properties in human skeletal muscle: support for the assumption that the “catch” state involves twitchin linkages between myofilaments. J Comp Physiol B 179:945–50

Backues SK and Klionsky DJ (2010) Autophagy gets in on the regulatory act. J Mol Cell Biol (in press)

Barany K, Rokolya A, Barany M (1990) Stretch activates myosin light chain kinase in arterial smooth muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 173:164–171

Barsyte-Lovejoy D, Galanis A, Clancy A, Sharrocks AD (2004) ERK5 is targeted to myocyte enhancer factor 2A (MEF2A) through a MAPK docking motif. Biochem J 381:693–9

Benian GM, Kiff JE, Neckelmann N, Moerman DG, Waterston RH (1989) Sequence of an unusually large protein implicated in regulation of myosin activity in C. elegans. Nature 342:45–50

Benian GM, Ayme-Southgate A, Tinley TL (1999) The genetics and molecular biology of the titin/connectin-like proteins of invertebrates. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 138:235–68

Bergmann O, Bhardwaj RD, Bernard S, Zdunek S, Barnabe-Heider F, Walsh S, Zupicich J, Alkass K, Buchholz BA, Druid H, Jovinge S, Frisen J (2009) Evidence for cardiomyocyte renewal in humans. Science 324:98–102

Bertz M, Wilmanns M, Rief M (2009) The titin-telethonin complex is a directed, superstable molecular bond in the muscle Z-disk. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:13307–133310

Bialik S, Kimchi A (2010) Lethal weapons: DAP-kinase, autophagy and cell death DAP-kinase regulates autophagy. Curr Opin Cell Biol 22:199–205

Boudeau J, Miranda-Saavedra D, Barton GJ, Alessi DR (2006) Emerging roles of pseudokinases. Trends Cell Biol 16:443–52

Butler TM, Siegman MJ (2011) A force-activated kinase in a catch smooth muscle. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 31:349–358.

Butler TM, Mooers SU, Narayan SR, Siegman MJ (2010) The N-terminal region of twitchin binds thick and thin contractile filaments: redundant mechanisms of catch force maintenance. J Biol Chem 285:40654–65

Cariou B, Perdereau D, Cailliau K, Browaeys-Poly E, Bereziat V, Vasseur-Cognet M, Girard J, Burnol AF (2002) The adapter protein ZIP binds Grb14 and regulates its inhibitory action on insulin signaling by recruiting protein kinase Czeta. Mol Cell Biol 22:6959–6970

Carlsson L, Yu J-G, Moza M, Carpen O, Thornell L-E (2007) Myotilin: a prominent marker of myofibrillar remodelling. Neuromuscul Disord 17:61–68

Chan JY, Takeda M, Briggs LE, Graham ML, Lu JT, Horikoshi N, Weinberg EO, Aoki H, Sato N, Chien KR, Kasahara H (2008) Identification of cardiac-specific myosin light chain kinase. Circ Res 102:571–80

Crowther LM, Wang SC, Eriksson NA, Myers S, Murray L and Muscat GE (2010) chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter-transcription factor II regulates nuclear receptor, myogenic and metabolic gene expression in skeletal muscle cells. Physiol Genomics (in press)

Dai KS, Liew CC (2001) A novel human striated muscle RING zinc finger protein, SMRZ, interacts with SMT3b via its RING domain. J Biol Chem 276:23992–23999

Däpp C, Schmutz S, Hoppeler H, Flück M (2004) Transcriptional reprogramming and ultrastructure during atrophy and recovery of mouse soleus muscle. Physiol Genomics 20:97–107

de Diego I, Kuper J, Bakalova N, Kursula P, Wilmanns M (2010) Molecular basis of the death-associated protein kinase-calcium/calmodulin regulator complex. Sci Signal 3:ra6 doi:10.1126/scisignal.2000552

de Tombe PP, Solaro RJ (2000) Integration of cardiac myofilament activity and regulation with pathways signaling hypertrophy and failure. Ann Biomed Eng 28:991–1001

Diaz-Meco MT, Moscat J (2001) MEK5, a new target of the atypical protein kinase C isoforms in mitogenic signaling. Mol Cell Biol 21:1218–27

Dietz H, Berkemeier F, Bertz M, Rief M (2006) Anisotropic deformation response of single protein molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:12724–8

Dinev D, Jordan BW, Neufeld B, Lee JD, Lindemann D, Rapp UR, Ludwig S (2001) Extracellular signal regulated kinase 5 (ERK5) is required for the differentiation of muscle cells. EMBO Rep 2:829–34

Duran A, Serrano M, Leitges M, Flores JM, Picard S, Brown JP, Moscat J, Diaz-Meco MT (2004) The atypical PKC-interacting protein p62 is an important mediator of RANK-activated osteoclastogenesis. Dev Cell 6:303–9

Durieux AC, Desplanches D, Freyssenet D, Fluck M (2007) Mechanotransduction in striated muscle via focal adhesion kinase. Biochem Soc Trans 35:1312–3

Ehler E, Gautel M (2008) The sarcomere and sarcomerogenesis. Adv Exp Med Biol 642:1–14

Farman GP, Allen EJ, Gore D, Irving TC, de Tombe PP (2007) Interfilament spacing is preserved during sarcomere length isometric contractions in rat cardiac trabeculae. Biophys J 92:L73–5

Fukuzawa A, Idowu S, Gautel M (2005) Complete human gene structure of obscurin: implications for isoform generation by differential splicing. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 26:427–34

Fukuzawa A, Lange S, Holt MR, Vihola A, Carmignac V, Ferreiro A, Udd AB, Gautel M (2008) Interactions with titin and myomesin target obscurin and its small homologue, obscurin-like 1, to the sarcomeric M-band: implications for hereditary myopathies. J Cell Sci 121:1841–1851

Funabara D, Hamamoto C, Yamamoto K, Inoue A, Ueda M, Osawa R, Kanoh S, Hartshorne DJ, Suzuki S, Watabe S (2007) Unphosphorylated twitchin forms a complex with actin and myosin that may contribute to tension maintenance in catch. J Exp Biol 210:4399–410

Gautel M (2008) The sarcomere and the nucleus: functional links to hypertrophy, atrophy and sarcopenia. Adv Med Biol Exp 642:176–191

Gautel M (2010) The sarcomeric cytoskeleton: who picks up the strain? Curr Opin Cell Biol 23:39–46.

Gautel M, Castiglione-Morelli M, Pfuhl M, Motta A, Pastore A (1995) A calmodulin-binding sequence in the C-terminus of human cardiac titin kinase. Eur J Biochem 230:752–759

Grater F, Shen J, Jiang H, Gautel M, Grubmuller H (2005) Mechanically induced titin kinase activation studied by force-probe molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys J 88:790–804

Greene D, Garcia T, Sutton B, Gernert KM, Benian GM, Oberhauser AF (2008) Single-molecule force spectroscopy reveals a stepwise unfolding of C. elegans giant protein kinase domains. Biophys J 95:1360–1370

Haglund K, Dikic I (2005) Ubiquitylation and cell signaling. EMBO J 24:3353–9

Hanks SK, Hunter T (1995) Protein kinases 6. The eukaryotic protein kinase superfamily: kinase (catalytic) domain structure and classification. FASEB J 9:576–96

Hatch V, Zhi G, Smith L, Stull JT, Craig R, Lehman W (2001) Myosin light chain kinase binding to a unique site on F-actin revealed by three-dimensional image reconstruction. J Cell Biol 154:611–7

Haworth RS, Cuello F, Herron TJ, Franzen G, Kentish JC, Gautel M, Avkiran M (2004) Protein kinase D is a novel mediator of cardiac troponin I phosphorylation and regulates myofilament function. Circ Res 95:1091–1099

Hayashi T, Arimura T, Itoh-Satoh M, Ueda K, Hohda S, Inagaki N, Takahashi M, Hori H, Yasunami M, Nishi H, Koga Y, Nakamura H, Matsuzaki M, Choi BY, Bae SW, You CW, Han KH, Park JE, Knoll R, Hoshijima M, Chien KR, Kimura A (2004) Tcap gene mutations in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 44:2192–201

Heierhorst J, Kobe B, Feil SC, Parker MW, Benian GM, Weiss KR, Kemp BE (1996) Ca2+/S100 regulation of giant protein kinases. Nature 380:636–9

Heierhorst J, Tang X, Lei J, Probst WC, Weiss KR, Kemp BE, Benian GB (1996) Substrate specificity and inhibitor sensitivity of Ca2+/S100-dependent protein kinases. Eur J Biochem 242:454–459

Holt LJ, Siddle K (2005) Grb10 and Grb14: enigmatic regulators of insulin action—and more? Biochem J 388:393–406

Hong F, Haldeman BD, John OA, Brewer PD, Wu YY, Ni S, Wilson DP, Walsh MP, Baker JE, Cremo CR (2009) Characterization of tightly associated smooth muscle myosin-myosin light-chain kinase-calmodulin complexes. J Mol Biol 390:879–92

Horowits R, Podolsky RJ (1987) The positional stability of thick filaments in activated skeletal muscle depends on sarcomere length: evidence for the role of titin filaments. J Cell Biol 105:2217–2223

Hoshijima M (2006) Mechanical stress-strain sensors embedded in cardiac cytoskeleton: Z disk, titin, and associated structures. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290:H1313–1325

Hu S-H, Parker MW, Lei JY, Wilce MCJ, Benian GM, Kemp BE (1994) Insights into autoregulation from the crystal structure of twitchin kinase. Nature 369:581–584

Huxley HE, Faruqi AR, Kress M, Bordas J, Koch MH (1982) Time-resolved X-ray diffraction studies of the myosin layer-line reflections during muscle contraction. J Mol Biol 158:637–84

Ikura M, Clore GM, Gronenborn AM, Zhu G, Klee CB, Bax A (1992) Solution structure of a calmodulin-target peptide complex by multi-dimensional NMR. Science 256:632–638

Johansen T, Lamark T (2011) Selective autophagy mediated by autophagic adapter proteins. Autophagy 7

Joung I, Strominger JL, Shin J (1996) Molecular cloning of a phosphotyrosine-independent ligand of the p56lck SH2 domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:5991–5995

Kamm KE, Stull JT (2001) Dedicated myosin light chain kinases with diverse cellular functions. J Biol Chem 276:4527–4530

Kirkin V, Lamark T, Sou YS, Bjorkoy G, Nunn JL, Bruun JA, Shvets E, McEwan DG, Clausen TH, Wild P, Bilusic I, Theurillat JP, Overvatn A, Ishii T, Elazar Z, Komatsu M, Dikic I, Johansen T (2009) A role for NBR1 in autophagosomal degradation of ubiquitinated substrates. Mol Cell 33:505–16

Kobe B, Heierhorst J, Feil SC, Parker MW, Benian GB, Weiss KR, Kemp BE (1996) Giant protein kinases: domain interactions and structural basis of autoregulation. EMBO J 15:6810–6821

Komatsu M, Waguri S, Koike M, Sou YS, Ueno T, Hara T, Mizushima N, Iwata J, Ezaki J, Murata S, Hamazaki J, Nishito Y, Iemura S, Natsume T, Yanagawa T, Uwayama J, Warabi E, Yoshida H, Ishii T, Kobayashi A, Yamamoto M, Yue Z, Uchiyama Y, Kominami E, Tanaka K (2007) Homeostatic levels of p62 control cytoplasmic inclusion body formation in autophagy-deficient mice. Cell 131:1149–63

Kontrogianni-Konstantopoulos A, Ackermann MA, Bowman AL, Yap SV, Bloch RJ (2009) Muscle giants: molecular scaffolds in sarcomerogenesis. Physiol Rev 89:1217–67

Kruger M, Linke WA (2009) Titin-based mechanical signalling in normal and failing myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol 46:490–498

Kudryashov DS, Stepanova OV, Vilitkevich EL, Nikonenko TA, Nadezhdina ES, Shanina NA, Lukas TJ, Van Eldik LJ, Watterson DM, Shirinsky VP (2004) Myosin light chain kinase (210 kDa) is a potential cytoskeleton integrator through its unique N-terminal domain. Exp Cell Res 298:407–417

Labeit S, Kolmerer B (1995) Titins: giant proteins in charge of muscle ultrastructure and elasticity. Science 270:293–296

Labeit S, Gautel M, Lakey A, Trinick J (1992) Towards a molecular understanding of titin. EMBO J 11:1711–1716

Lange S, Xiang F, Yakovenko A, Vihola A, Hackman P, Rostkova E, Kristensen J, Brandmeier B, Franzen G, Hedberg B, Gunnarsson LG, Hughes SM, Marchand S, Sejersen T, Richard I, Edstrom L, Ehler E, Udd B, Gautel M (2005) The kinase domain of titin controls muscle gene expression and protein turnover. Science 308:1599–1603

Lange S, Ehler E, Gautel M (2006) From A to Z and back? Multicompartment proteins in the sarcomere. Trends Cell Biol 16:11–18

Ledvora R, Barany K, VanderMeulen D, Barron J, Barany M (1983) Stretch-induced phosphorylation of the 20,000-dalton light chain of myosin in arterial smooth muscle. J Biol Chem 258:14080–14083

Lee EH, Hsin J, Sotomayor M, Comellas G, Schulten K (2009) Discovery through the computational microscope. Structure 17:1295–306

Linke WA, Kruger M (2010) The giant protein titin as an integrator of myocyte signaling pathways. Physiol Bethesda 25:186–98

Manning G, Whyte DB, Martinez R, Hunter T, Sudarsanam S (2002) The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science 298:1912–34

Mao J, Luo H, Han B, Bertrand R, Wu J (2009) Drak2 is upstream of p70S6 kinase: its implication in cytokine-induced islet apoptosis, diabetes, and islet transplantation. J Immunol 182:4762–70

Marcus SL, Winrow CJ, Capone JP, Rachubinski RA (1996) A p56(lck) ligand serves as a coactivator of an orphan nuclear hormone receptor. J Biol Chem 271:27197–200

Mardakheh FK, Yekezare M, Machesky LM, Heath JK (2009) Spred2 interaction with the late endosomal protein NBR1 down-regulates fibroblast growth factor receptor signaling. J Cell Biol 187:265–77

Markert CD, Meaney MP, Voelker KA, Grange RW, Dalley HW, Cann JK, Ahmed M, Bishwokarma B, Walker SJ, Yu SX, Brown M, Lawlor MW, Beggs AH, Childers MK (2010) Functional muscle analysis of the Tcap knockout mouse. Hum Mol Genet 19:2268–2283

Maruyama K (1976) Connectin, an elastic protein from myofibrils. J Biochem 80:405–407

Masiero E, Sandri M (2010) Autophagy inhibition induces atrophy and myopathy in adult skeletal muscles. Autophagy 6:307–309

Mason P, Bayol S, Loughna PT (1999) The novel sarcomeric protein telethonin exhibits developmental and functional regulation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 257:699–703

Mayans O, Van der Ven P, Wilm M, Mues A, Young P, Fürst DO, Wilmanns M, Gautel M (1998) Structural basis of the activation of the titin kinase domain during myofibrillogenesis. Nature 395:863–869

McElhinny MS, Kakinuma K, Sorimachi H, Labeit S, Gregorio CC (2002) Muscle-specific RING finger-1 interacts with titin to regulate sarcomeric M-line and thick filament structure and may have nuclear functions via its interaction with glucocorticoid modulatory element binding protein-1. J Cell Biol 157:125–136

Moreira ES, Wiltshire TJ, Faulkner G, Nilforoushan A, Vainzof M, Suzuki OT, Valle G, Reeves R, Zatz M, Passos-Bueno MR, Jenne DE (2000) Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 2G is caused by mutations in the gene encoding the sarcomeric protein telethonin. Nat Genet 24:163–6

Mukherjee K, Sharma M, Jahn R, Wahl MC, Sudhof TC (2010) Evolution of CASK into a Mg2+-sensitive kinase. Sci Signal 3:ra33

Murton AJ, Constantin D, Greenhaff PL (2008) The involvement of the ubiquitin proteasome system in human skeletal muscle remodelling and atrophy. Biochim Biophys Acta 1782:730–43

Myers SA, Wang SC, Muscat GE (2006) The chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter-transcription factors modulate genes and pathways involved in skeletal muscle cell metabolism. J Biol Chem 281:24149–60

Nakamura K, Kimple AJ, Siderovski DP, Johnson GL (2010) PB1 domain interaction of p62/sequestosome 1 and MEKK3 regulates NF-kappaB activation. J Biol Chem 285:2077–89

Nicol RL, Frey N, Pearson G, Cobb M, Richardson J, Olson EN (2001) Activated MEK5 induces serial assembly of sarcomeres and eccentric cardiac hypertrophy. EMBO J 20:2757–67

Obermann WMJ, Gautel M, Steiner F, Van der Ven P, Weber K, Fürst DO (1996) The structure of the sarcomeric M band: localization of defined domains of myomesin, M-protein and the 250 kD carboxy-terminal region of titin by immunoelectron microscopy. J Cell Biol 134:1441–1453

Ochala J, Gustafson A-M, Lano Diez M, Renaud G, Li M, Aare S, Qaisar R, Banduseela VC, Hedstrom Y, Tang X, Dworkin B, Ford GC, Nair S, Perera S, Gautel M, Larsson L (2011) Preferential skeletal muscle myosin loss in response to mechanical silencing in a novel rat intensive care unit model: underlying mechanisms. J Physiol (in press)

Okada K, Yanagawa T, Warabi E, Yamastu K, Uwayama J, Takeda K, Utsunomiya H, Yoshida H, Shoda J, Ishii T (2009) The alpha-glucosidase inhibitor acarbose prevents obesity and simple steatosis in sequestosome 1/A170/p62 deficient mice. Hepatol Res 39:490–500

O'Neil KT, DeGrado WF (1990) How calmodulin binds its targets: sequence independent recognition of amphiphilic alpha-helices. Trends Biochem Sci 15:59–64

Pankiv S, Clausen TH, Lamark T, Brech A, Bruun J-A, Outzen H, Overvatn A, Bjorkoy G, Johansen T (2007) p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. J Biol Chem 282:24131–24145

Park I, Chung J, Walsh CT, Yun Y, Strominger JL, Shin J (1995) Phosphotyrosine-independent binding of a 62-kDa protein to the src homology 2 (SH2) domain of p56lck and its regulation by phosphorylation of Ser-59 in the lck unique N-terminal region. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92:12338–42

Perera S, Holt MR, Mankoo BS, Gautel M (2011) Developmental regulation of MURF ubiquitin ligases and autophagy proteins nbr1, p62/SQSTM1 and LC3 during cardiac myofibril assembly and turnover. Dev Biol 351:46–61 [Epub ahead of print Dec 22, 2010]

Pernigo S, Fukuzawa A, Bertz M, Holt M, Rief M, Steiner RA, Gautel M (2010) Structural insight into M-band assembly and mechanics from the titin-obscurin-like-1 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:2908–2913

Piazzesi G, Reconditi M, Linari M, Lucii L, Bianco P, Brunello E, Decostre V, Stewart A, Gore DB, Irving TC, Irving M, Lombardi V (2007) Skeletal muscle performance determined by modulation of number of myosin motors rather than motor force or stroke size. Cell 131:784–95

Pizon V, Iakovenko A, Van der Ven PFM, Kelly RA, Fatu C, Fürst DO, Karsenti E, Gautel M (2002) Transient association of titin and myosin with microtubules in nascent myofibrils directed by the MURF2 RING-finger protein. J Cell Sci 115:4469–4482

Puchner EM, Gaub HE (2009) Force and function: probing proteins with AFM-based force spectroscopy. Curr Opin Struct Biol 19:605–14

Puchner E, Alexandrovich A, Kho AL, Hensen U, Schäfer LV, Brandmeier B, Gräter F, Grubmuller H, Gaub HE, Gautel M (2008) Mechanoenzymatics of titin kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:13385–13390

Puls A, Schmidt S, Grawe F, Stabel S (1997) Interaction of protein kinase C zeta with ZIP, a novel protein kinase C- binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:6191–6

Puri PL, Wu Z, Zhang P, Wood LD, Bhakta KS, Han J, Feramisco JR, Karin M, Wang JY (2000) Induction of terminal differentiation by constitutive activation of p38 MAP kinase in human rhabdomyosarcoma cells. Genes Dev 14:574–584

Rabiller M, Getlik M, Kluter S, Richters A, Tuckmantel S, Simard JR, Rauh D (2010) Proteus in the world of proteins: conformational changes in protein kinases. Arch Pharm Weinheim 343:193–206

Rabiner CA, Mains RE, Eipper BA (2005) Kalirin: a dual rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor that is so much more than the sum of its many parts. Neuroscientist 11:148–160

Rajakulendran T, Sicheri F (2010) Allosteric protein kinase regulation by pseudokinases: insights from STRAD. Sci Signal 3:pe8

Rellos P, Pike AC, Niesen FH, Salah E, Lee WH, von Delft F, Knapp S (2010) Structure of the CaMKIIdelta/calmodulin complex reveals the molecular mechanism of CaMKII kinase activation. PLoS Biol 8:e1000426

Rief M, Gautel M, Oesterhelt F, Fernandez JM, Gaub HE (1997) Reversible unfolding of individual titin Ig-domains by AFM. Science 276:1109–1112

Russell MW, Raeker MO, Korytkowski KA, Sonneman KJ (2002) Identification, tissue expression and chromosomal localization of human Obscurin-MLCK, a member of the titin and Dbl families of myosin light chain kinases. Gene 282:237–46

Sack MN, Disch DL, Rockman HA, Kelly DP (1997) A role for Sp and nuclear receptor transcription factors in a cardiac hypertrophic growth program. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:6438–43

Sadikot T, Hammond CR, Ferrari MB (2010) Distinct roles for telethonin N-versus C-terminus in sarcomere assembly and maintenance. Dev Dyn 239:1124–1135

Sandri M (2008) Signaling in muscle atrophy and hypertrophy. Physiol Bethesda 23:160–70

Sanz L, Sanchez P, Lallena MJ, Diaz-Meco MT, Moscat J (1999) The interaction of p62 with RIP links the atypical PKCs to NF-kappaB activation. EMBO J 18:3044–3053

Sanz L, Diaz-Meco MT, Nakano H, Moscat J (2000) The atypical PKC-interacting protein p62 channels NF-kappaB activation by the IL-1-TRAF6 pathway. EMBO J 19:1576–86

Schröder R, Iakovenko A, Reimann J, Mues A, Bönnemann C, Matten J, Gautel M (2001) Early and selective downregulation of telethonin in neurogenic atrophy. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 22:259–264

Seibenhener ML, Geetha T, Wooten MW (2007) Sequestosome 1/p62—more than just a scaffold. FEBS Lett 581:175–9

Seipel K, O'Brien S, Iannotti E, Medley Q, Streuli M (2001) Tara, a novel F-actin binding protein, associates with the Trio guanine nucleotide exchange factor and regulates actin cytoskeletal organization. J Cell Sci 114:389–399

Sellers JR, Pato MD (1984) The binding of smooth muscle myosin light chain kinase and phosphatases to actin and myosin. J Biol Chem 259:7740–6

Skamnaki VT, Owen DJ, Noble ME, Lowe ED, Lowe G, Oikonomakos NG, Johnson LN (1999) Catalytic mechanism of phosphorylase kinase probed by mutational studies. Biochemistry 38:14718–30

Spencer JA, Eliazer S, Ilaria RL Jr, Richardson JA, Olson EN (2000) Regulation of microtubule dynamics and myogenic differentiation by MURF, a striated muscle RING-finger protein. J Cell Biol 150:771–84

Sudo T, Maruyama M, Osada H (2000) p62 functions as a p38 MAP kinase regulator. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 269:521–5

Sun L, Chen ZJ (2004) The novel functions of ubiquitination in signaling. Curr Opin Cell Biol 16:119–126

Tasca G, Mirabella M, Broccolini A, Monforte M, Sabatelli M, Biscione GL, Piluso G, Gualandi F, Tonali PA, Udd B, Ricci E (2010) An Italian case of hereditary myopathy with early respiratory failure (HMERF) not associated with the titin kinase domain R279W mutation. Neuromuscul Disord 20:730–4

Taylor SS, Kornev AP (2010) Protein kinases: evolution of dynamic regulatory proteins. Trends Biochem Sci 36:65–77. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2010.09.006

Taylor SS, Kornev AP (2010) Yet another “active” pseudokinase, Erb3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:8047–8

Taylor SS, Radzio-Andzelm E (1994) Three protein kinase structures define a common motif. Structure 2:345–55

Tskhovrebova L, Trinick J (2003) Titin: properties and family relationships. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4:679–89

Valiev M, Yang J, Adams JA, Taylor SS, Weare JH (2007) Phosphorylation reaction in cAPK protein kinase-free energy quantum mechanical/molecular mechanics simulations. J Phys Chem B 111:13455–64

Vogel V (2006) Mechanotransduction involving multimodular proteins: converting force into biochemical signals. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 35:459–88

Wang K, McClure J, Tu A (1979) Titin: major myofibrillar components of striated muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 76:3698–3702

Wang X, Merritt AJ, Seyfried J, Guo C, Papadakis ES, Finegan KG, Kayahara M, Dixon J, Boot-Handford RP, Cartwright EJ, Mayer U, Tournier C (2005) Targeted deletion of mek5 causes early embryonic death and defects in the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5/myocyte enhancer factor 2 cell survival pathway. Mol Cell Biol 25:336–345

Waters S, Marchbank K, Solomon E, Whitehouse C, Gautel M (2009) Interactions with LC3 and polyubiquitin chains link nbr1 to autophagic protein turnover. FEBS Lett 583:1846–52

Weinert S, Bergmann N, Luo X, Erdmann B, Gotthardt M (2006) M line-deficient titin causes cardiac lethality through impaired maturation of the sarcomere. J Cell Biol 173:559–70

Weitkamp B, Jurk K, Beinbrech G (1998) Projectin-thin filament interactions and modulation of the sensitivity of the actomyosin ATPase to calcium by projectin kinase. J Biol Chem 273:19802–8

Whitehouse C, Chambers J, Howe K, Cobourne M, Sharpe P, Solomon E (2002) NBR1 interacts with fasciculation and elongation protein zeta-1 (FEZ1) and calcium and integrin binding protein (CIB) and shows developmentally restricted expression in the neural tube. Eur J Biochem 269:538–45

Whitehouse CA, Waters S, Marchbank K, Horner A, McGowan NW, Jovanovic JV, Xavier GM, Kashima TG, Cobourne MT, Richards GO, Sharpe PT, Skerry TM, Grigoriadis AE, Solomon E (2010) Neighbor of Brca1 gene (Nbr1) functions as a negative regulator of postnatal osteoblastic bone formation and p38 MAPK activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:12913–8

Wickstrom SA, Lange A, Montanez E, Fassler R (2010) The ILK/PINCH/parvin complex: the kinase is dead, long live the pseudokinase! EMBO J 29:281–91

Willis MS, Ike C, Li L, Wang DZ, Glass DJ, Patterson C (2007) Muscle ring finger 1, but not muscle ring finger 2, regulates cardiac hypertrophy in vivo. Circ Res 100:456–9

Willis MS, Zungu M, Patterson C (2010) Cardiac muscle ring finger-1—friend or foe? Trends Cardiovasc Med 20:12–6

Wooten MW, Seibenhener ML, Mamidipudi V, Diaz-Meco MT, Barker PA, Moscat J (2001) The atypical protein kinase C-interacting protein p62 Is a scaffold for NF-kB activation by nerve growth factor. J Biol Chem 276:7709–7712

Yang CX, Chen HQ, Chen C, Yu WP, Zhang WC, Peng YJ, He WQ, Wei DM, Gao X, Zhu MS (2006) Microfilament-binding properties of N-terminal extension of the isoform of smooth muscle long myosin light chain kinase. Cell Res 16:367–376

Ye LH, Hayakawa K, Kishi H, Imamura M, Nakamura A, Okagaki T, Takagi T, Iwata A, Tanaka T, Kohama K (1997) The structure and function of the actin-binding domain of myosin light chain kinase of smooth muscle. J Biol Chem 272:32182–9

Young P, Ehler E, Gautel M (2001) Obscurin, a giant sarcomeric Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor protein involved in sarcomere assembly. J Cell Biol 154:123–136

Zalckvar E, Berissi H, Mizrachy L, Idelchuk Y, Koren I, Eisenstein M, Sabanay H, Pinkas-Kramarski R, Kimchi A (2009) DAP-kinase-mediated phosphorylation on the BH3 domain of beclin 1 promotes dissociation of beclin 1 from Bcl-XL and induction of autophagy. EMBO Rep 10:285–92

Zetser A, Gredinger E, Bengal E (1999) p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway promotes skeletal muscle differentiation. Participation of the Mef2c transcription factor. J Biol Chem 274:5193–5200

Zou P, Pinotsis N, Lange S, Song Y-H, Popov A, Mavridis I, Mayans O, Gautel M, Wilmanns M (2006) Palindromic assembly of the giant muscle protein titin in the sarcomeric Z-disk. Nature 439:229–233

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges the generous support by the British Heart Foundation, the Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust. Many thanks to Ulf Hensen and Helmut Grubmüller for coordinates of mechanically opened TK.

Structure figures were generated with PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.3, Schrödinger, LLC.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This is an invited review for the DeTombe/Granzier Special Issue on “The cytoskeleton and the cellular transduction of mechanical strain”.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Gautel, M. Cytoskeletal protein kinases: titin and its relations in mechanosensing. Pflugers Arch - Eur J Physiol 462, 119–134 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00424-011-0946-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00424-011-0946-1