Abstract

Purpose

Metastatic oesophageal cancer is commonly considered as a palliative situation with a poor prognosis. However, there is increasing evidence that well-selected patients with a limited number of liver metastases (ECLM) may benefit from a multimodal approach including surgery.

Methods

A systematic review of the current literature for randomized trials, retrospective studies, and case series with patients undergoing hepatectomies for oesophageal and oesophagogastric junction cancer liver metastases was conducted up to the 31st of August 2021 using the MEDLINE (PubMed) and Cochrane Library databases.

Results

A total of 661 articles were identified. After removal of duplicates, 483 articles were screened, of which 11 met the inclusion criteria. The available literature suggests that ECLM resection in patients with liver oligometastatic disease may lead to improved survival and even long-term survival in some cases. The response to concomitant chemotherapy and liver resection seems to be of significance. Furthermore, a long disease-free interval in metachronous disease, low number of liver metastases, young age, and good overall performance status have been described as potential predictive markers of outcome for the resection of liver metastases.

Conclusion

Surgery may be offered to carefully selected patients to potentially improve survival rates compared to palliative treatment approaches. Studies with standardized patient selection criteria and treatment protocols are required to further define the role for surgery in ECLM. In this context, particular consideration should be given to neoadjuvant treatment concepts including immunotherapies in stage IVB oesophageal and oesophagogastric junction cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The treatment of oesophageal cancer has markedly improved over the last decades. Embedded in a multimodal treatment concept, 5-year survival rates around 50% can be achieved given the absence of distant metastatic disease [1, 2]. However, patients with stage IVB oesophageal cancer are generally treated in a palliative intention with chemotherapy or best supportive care and have a poor median survival between 4 and 8 months [3].

Hepatic metastases remain one of the most common sites of distant dissemination in oesophageal cancer (EC) with an incidence of 35–40% at the time of diagnosis. It also represents the first site of recurrence in 6–25% of cases after oesophagectomy with curative intent [4, 5].

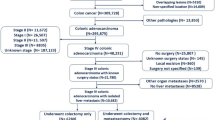

Over the last decades, liver resections for metastatic cancer have become a standard treatment for defined tumour entities, especially in patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) and neuroendocrine tumours. Overall perioperative mortality rates between 1 and 5% have been reported, although a high dependency on case load per centre and the average extent of liver surgeries (minor resections up to extended hepatectomies) have to be taken into consideration when comparing these studies [6,7,8]. However, 5-year overall survival (OS) rates over 50% was achievable in patients who underwent liver resections for CRC liver metastases [9, 10].

The role for liver resections in liver oligometastatic EC remains controversial and the available literature is scarce. Some studies reported improved survival rates in patients, who underwent oesophageal cancer liver metastases (ECLM) resection, if compared to palliative treatment alone [11,12,13]. Other studies reported little or no survival benefit, which raises the question what criteria might help to stratify patients that may benefit from a surgical approach [14, 15]. This article provides an overview of the available literature and the role for surgery in patients with ECLM.

Methods

A systematic literature search was conducted using the MEDLINE (PubMed) and Cochrane Library databases. Studies with cancer patients undergoing surgery for oesophageal or gastroesophageal cancer liver metastases were included, if an appropriate follow-up with information on survival following surgery was available. The search strategy included combinations of the following keywords: ‘esophageal cancer’, ‘esophagogastric junction cancer’, ‘gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma’, ‘liver resection’, ‘hepatectomy’, and ‘metastasectomy’.

Only original articles in English were considered for this systematic review. Case reports and case series with less than 4 patients were excluded. Studies with patients, who underwent liver resections for multiple tumour entities, were excluded, if there was no sufficient subgroup data available on patients with oesophageal or oesophagogastric junction cancer liver metastases.

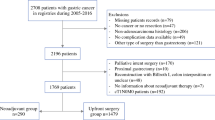

The search was carried out until the 31st of August 2021 and identified 653 articles. Further 8 articles were added from the references of other systematic reviews. After removal of duplicates, 483 articles were screened. Following this, 407 articles were excluded as abstracts and titles did not meet the inclusion criteria. The remaining 76 articles were reviewed by full text. Finally, 11 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review.

Resection for non-colorectal/non-neuroendocrine liver metastases

The surgical treatment for colorectal and neuroendocrine liver metastases has become the standard of care, given that a complete curative resection can be achieved [16, 17]. However, liver metastasis resection for non-colorectal/non-neuroendocrine primary tumours remains a controversial issue and no clear international level 1 recommendations are available, with many basing practice on case series and anecdotal evidence. Some studies demonstrate improved short-term survival rates and even long-term survival in patients, who underwent resections for non-colorectal/non-neuroendocrine liver metastases (NCNNLM) [18,19,20,21]. Following the resection of NCNNLM, 5-year overall survival rates between 30 and 61% have been reported [18, 20, 21]. However, direct correlations on reported survival rates cannot be drawn due to heterogeneity of primary tumours and the percentage of patients with ECLM within these studies is generally very low to zero. It has been demonstrated that the survival advantage depends on the primary site with patients undergoing resection for genitourinary liver metastases benefitting the most in terms of overall survival [22]. Patients with liver metastases from gastroesophageal primaries were found to have less favourable results with a median survival between 16 and 26 months [18, 22, 23].

However, a recent study from 2018 analysed 1792 patients with metastatic adenocarcinoma of the stomach, the oesophagogastric junction, and the distal oesophagus [24]. Of these, 92 patients (5%) underwent metastasectomy with the most common metastatic sites being peritoneal (29%), hepatic (24%), and distant lymph nodes (11%). The study included two patients with oesophageal and ten patients with oesophagogastric junction primaries. Patients, who underwent surgery for metastatic disease, had higher survival rates compared to conservatively treated patients. The median OS after metastasectomy was 16.7 months with a 3-year OS after surgery of 30.6%, which is beyond the results that can be achieved with palliative chemotherapy alone [3].

Similar results were provided by Schmidt et al., who reported a median survival of 21.3 months with a 3-year OS of 29.5% and a 5-year OS of 21.9% in 112 patients with metastatic gastric or oesophagogastric junction cancer that underwent surgical resection [25]. Badgwell et al. demonstrated a 5-year OS of 25% in 82 patients after resection of oesophagogastric cancer metastases [26]. The subgroup of patients, in whom solid organ metastases were resected, had an even higher 5-year OS of 34%. Another study by Andreou et al. reported a median survival of 18 months in 47 patients undergoing hepatectomy for oesophagogastric cancer metastases with 3- and 5-year OS rates of 37% and 24%, respectively [27].

Taken together, the resection of NCNNLM from gastroesophageal primaries may offer improved survival rates, although clear selection criteria for patients benefitting from a surgical approach have not yet been defined. However, the above-mentioned studies with metastatic gastroesophageal cancers may not be transferable to EC patients as they mostly consisted of patients with gastric and oesophagogastric junction adenocarcinomas and, if any, a negligible number of distal oesophageal AC. Similarly, there were no patients with oesophageal SCC in these studies (Table 1).

Liver resection for oesophageal cancer liver metastases

The literature on patients that underwent surgery for ECLM is scant. The few available studies are of retrospective design with low patient numbers and are significantly biased by patient selection (Table 2). However, there is data that may encourage a more aggressive multimodal treatment approach including surgery in selected patients with stage IVB EC [28,29,30,31].

The authors of a retrospective study from 2016 identified 96 patients with stage IVB EC that were treated with chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CRT) [32]. A subset of 14 patients also received surgery (11 patients for non-regional lymph node metastases, 3 patients for distant organ metastases). The median OS of all patients was 21.0 months. The median OS in the subgroup of patients that received surgery was not reached and a corresponding 5-year OS rate of 50.5% was reported vs 20 months and a 5-year OS rate of 11.7% for those without surgery. However, there was a strong patient selection bias as patients in the group receiving surgery tended to be younger and were less likely to have distant organ metastases.

In 2015, Huddy et al. published a case series that included four patients that underwent liver resection for metachronous liver metastases following a curatively intended oesophagectomy [12]. Two out of the four patients were still alive and without evidence for recurrent disease 22 and 92 months after liver resection. Adam et al. found a median OS of 16 months and a 3-year survival rate of 32% in patients, who underwent resection for synchronous and metachronous ECLM [18]. Similar survival rates were reported by Liu and colleagues, who published a retrospective study with 69 consecutive patients with metachronous, solitary ECLM [33]. A subgroup of 26 patients underwent liver resection, whereas the remaining 43 patients were treated conservatively with chemotherapy and additional local therapies including radiofrequency ablation (n = 16), high intensity focused ultrasound (n = 12), or microwave ablation (n = 15). Patients in the surgical group had significantly higher 1- and 2-year survival rates compared to the non-surgically treated patients (50.8% and 21.2% vs. 31% and 7.1%, p = 0.027 and < 0.05, respectively).

A recently published study by Seesing et al. included 34 patients, in whom a resection of gastroesophageal cancer metastases was performed [5]. Of these patients, 19 received a resection of hepatic metastases and 15 a resection of pulmonary metastases. A subgroup analysis of the patients with ECLM (n = 11) revealed a median OS of 52 months and a 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS of 91%, 55%, and 27%, respectively. The survival after pulmonary metastasectomy (n = 11) was even higher with 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS of 82%, 64%, and 64%, respectively. Similar results were provided by Van Deale et al. in a retrospective study consisting of 12 patients with EC and synchronous liver (n = 6) or lymph node metastases (n = 5) as well as one patient with liver and lymph node metastases [13]. Ten patients underwent an Ivor-Lewis oesophagectomy with a two-field lymphadenectomy. The metastatic liver lesions were treated synchronously via wedge resection (n = 4), radiofrequency ablation (n = 1), or microwave ablation (n = 1); the five patients with distant lymph node metastases underwent surgical resection. After a median follow-up of 22 months, 50% of the surgically resected patients were still alive with 33% being free of disease recurrence.

Ichida et al. conducted a retrospective study that included 315 patients, who had undergone curatively intended oesophagectomies [11]. During a median follow-up period of 47 months, 138 patients (47%) developed disease recurrence. Five out of 26 patients with hepatic recurrences were treated with hepatic metastasectomy. A trend towards an improved survival in the group receiving surgery vs. no surgery could be observed (median OS 13 vs. 5 months). However, the non-surgically treated patients had either multinodular hepatic recurrence and/or additional extrahepatic recurrence or a poor general performance status, which makes a direct comparison with the surgically treated patients difficult. Nonetheless, there was one patient after hepatic resection, who was still alive and without evidence of recurrent disease 70 months after recurrence detection.

A recently published article reviewed studies and case reports with patients suffering from liver oligometastatic EC [4]. The authors concluded that surgery seems to be the treatment of choice for resectable ECLM, especially for patients with 3 or less lesions. However, the review included only retrospective studies and small case reports/case series. Due to their significant heterogeneity, patient selection bias, small patient numbers, and a lack of defined treatment protocols, these studies may not support such definite conclusions.

Nevertheless, the survival rates provided by Seesing and van Daele following ECLM resection are very encouraging [5, 13]. Therefore, the authors suggest to discuss the option of ECLM resection in MDT meetings, especially for suitable patients with liver oligometastatic disease.

Factors associated with an improved survival after resection of ECLM

Preoperative chemotherapy

As most of the studies with patients undergoing ECLM resection included only small patient numbers, the role of preoperative (palliative/neoadjuvant) chemotherapy has not been assessed appropriately. However, there is some evidence that preoperative chemotherapy may positively impact on survival rates, as a response to chemotherapy or a lack of progression was either a positive prognostic marker in surgically treated metastatic gastroesophageal cancer patients or it was used as selection criterion for a surgical approach in ECLM in the first place [12, 13, 24, 25, 27]. However, this could be more accurate for patients with synchronous ECLM that were often treated with simultaneous resection of the primary tumour and the metastasis(-es). Seesing and colleagues demonstrated superior survival rates in patients with predominantly metachronous liver metastases that underwent surgery to a large extent without prior chemotherapy [5]. On the contrary, all five patients in the study by Ichida et al. underwent surgery for metachronous ECLM without prior chemotherapy and had a relatively poor median survival of 13 months postmetastasectomy [11].

Wang et al. investigated the impact of a multimodal treatment approach in stage IVB EC that included surgery of the primary tumour and the metastatic lesion in selected cases [32]. All patients (n = 96) received palliative chemotherapy followed by concurrent CRT. Of these, 14 patients also underwent surgery as mentioned above. In a multivariate analysis, the radiographic response of the primary tumour to induction chemotherapy (complete vs incomplete) was associated with an improved OS. A radiologic complete response was defined as a lack of residual SUV after treatment assessed via PET/CT. When concurrent CRT response variables were not included in the multivariate analysis, the receipt of surgery was a significant independent predictor of improved OS and disease-free survival (DFS). Intriguingly, the radiographic response of the primary tumour to induction chemotherapy or concurrent CRT appeared to be of more significance than the response of the metastatic lesions.

Another study from 2015 included 112 patients with metastatic gastric or oesophagogastric junction adenocarcinomas that underwent surgical resection [25]. In the subgroup of patients that received neoadjuvant treatment (n = 72), the clinical responders (defined by a decrease of the maximal transversal primary tumour diameter of > 50% measured on CT and a decrease of the endoluminal tumour size of > 75% on endoscopic findings) had a significantly prolonged median survival compared to the non-responders (77.3 months vs 23.5 months; p < 0.001). Moreover, the group that did not receive preoperative chemotherapy had a significantly reduced median survival compared to the group, in which a preoperative chemotherapy was administered (11.0 months vs 31.1 months, p < 0.001). Therefore, the authors of the study concluded that a primary resection is not appropriate for patients with metastatic gastroesophageal cancer.

Similar findings were provided by Andreou et al., who published a retrospective study with 47 gastroesophageal cancer patients, in whom hepatic resections for mainly synchronous liver metastases were performed [27]. Of these, 32 patients underwent a simultaneous resection of the primary tumour and hepatic metastases. In the multivariate analysis, not undergoing preoperative chemotherapy was significantly associated with poor survival (5-year OS: 9% vs 45%, p = 0.005). In the subset of patients receiving preoperative chemotherapy (n = 20), the patients responding to the preoperative treatment or with stable disease on radiographic imaging (n = 13) had a significantly improved OS compared to those with progressive disease (n = 7) (5-year OS rate: 70% vs 0%, p = 0.045).

As opposed to the two studies mentioned above, a Dutch study reported superior survival rates in 19 patients with hepatic metastases from gastroesophageal primaries (8 × gastric primary, 11 × oesophageal primary), of which only 4 received neoadjuvant treatment prior to metastasectomy [5]. After resection of the predominantly metachronous liver metastases (17 × deriving from AC, 2 × from SCC), the median OS was 28 months and the 3- and 5-year survival rates were 41% and 31%, respectively. These contrary findings can lead to the conclusion that synchronous and metachronous liver metastases from gastroesophageal primaries have a differing underlying tumour biology and may require different patient selection criteria and treatment approaches.

However, the timing after receipt of preoperative (palliative) chemotherapy may play a pivotal role that needs to be taken into consideration when patients with ECLM are evaluated for surgery as the group around Carmona-Bayonas found that a longer duration of chemotherapy prior to surgery increases mortality (HR 1.04, p = 0.009) [24].

Patient and tumour-related factors

In a study from 2014 on 23 patients with pulmonary, predominantly metachronous metastases from oesophageal SCC, a short disease-free interval (DFI) < 12 months was associated with poor survival (p = 0.02) [34]. These results were in keeping with previous study results from 2008 [35]. Liu et al. could show similar results for patients with ECLM [33]. In this study, the outcomes of patients that underwent surgery for metachronous ECLM were compared with a group of non-surgically treated patients. A DFI > 12 months was associated with a significantly improved survival rate in both groups (p [both] < 0.05). Seesing and colleagues reported superior survival rates in 11 patients following the resection of mainly metachronous ECLM [5]. The patients included in the study had a DFI between 11 and 27 months, which supports the assumption that patients with a longer DFI may benefit from surgery. Conversely, Ichida et al. reported a median DFI of 6 months (0–14) in patients that underwent ECLM resection [11]. The study could not demonstrate a survival benefit of the surgically treated patients compared to a group that was treated conservatively (median survival 13 vs 5 months, p = 0.06).

The differentiation of the tumour may also have prognostic relevance when evaluating patients for ECLM resection. Poorly differentiated primary tumours have been mentioned as negative prognostic markers in metastatic EC [34].

Moreover, a complete resection of all tumour manifestations with overall clear resection margins (R0-resection) was reported to have a significant impact on survival rates in limited metastatic gastroesophageal cancers [25, 27, 32, 36]. Schmidt et al. demonstrated that complete resection of the primary tumour and the metastases in these patients lead to a significantly improved median survival of 29.5 months compared to patients with incomplete resection (R1/2) (p = 0.003) [25]. Andreou et al. could show that an R1-resection in patients that underwent hepatectomy for oesophagogastric cancer was associated with a poor OS [27]. Chao and colleagues revealed that scheduled surgery following CRT in patients with oesophageal SCC and distant nodal metastases (nodal M1a/b disease) leads to a survival benefit only in patients, in whom an R0-resection had been achieved (median OS 45 months vs 9.5 months after incomplete resection and 10.5 months in patients receiving definitive CRT, p = 0.0013) [36]. Analogously, the two studies with the longest OS following ECLM resection had high rates of R0-resections of about 90% [5, 13].

In the available literature, only patients with a low number of liver metastases/metastatic deposits underwent resection of ECLM. In the two studies with the longest OS after resection of ECLM, 77% (n = 20) of the patients had solitary liver metastases, 15% (n = 4) had two liver lesions, and only one patient was treated for 3 liver metastases [5, 13]. Although significantly affected by selection bias, these results may indicate that patients with a low metastatic burden could potentially benefit from a surgical approach. Therefore, a thorough preoperative radiographic imaging including CT, MRI, PET-CT, and (endoscopic) ultrasound/CEUS is of utmost importance [37].

Furthermore, the patients’ age and performance status need to be taken into account like in other areas where major surgery is being considered as young and relatively fit patients with stage IVB EC seem to benefit from an aggressive multimodal therapy including surgery [32].

The response to chemotherapy seems to be a significant factor in patients undergoing ECLM resection (this may also hold true for the response to targeted therapies/immunotherapies, although studies referring to this are not available as of yet). Therefore, in patients with a good response to chemotherapy and/or other potentially favourable factors such as a long disease-free interval in metachronous disease, low number of liver metastases, young age, and good overall performance status, ECLM resection should be considered, if an R0 resection status is achievable.

Discussion

Liver resections for liver oligometastatic EC remain a controversial issue as the available data is scarce and often of poor quality. Nevertheless, the few available studies demonstrated a survival benefit in patients that underwent liver resections in stage IVB EC, if compared to palliative chemotherapy only [3, 13]. In highly selected patients, 5-year survival rates up to 27% have been reported [5]. Even a chance for long-term survival seems possible [11, 12]. However, the main limitation of all the available studies on ECLM resection is that they are significantly biased. The lack of consistent patient selection criteria and treatment protocols disallow any definite conclusions as to whether ECLM resection should be part of the common armamentarium in the treatment of metastatic EC. Nevertheless, although being of limited validity, the available data speaks against the proposition that there is no role for surgery in metastatic EC. Patients with liver oligometastatic EC that responded well to palliative chemotherapy/CRT or with a long DFI > 12 months after primary surgery may benefit from ECLM resection, given a good performance status and the chance of a complete resection of all tumour manifestations [5, 27, 32, 33]. At the same time, the potential intraoperative and/or postoperative complications of liver resections need to be taken into account. In spite of the improvements in surgical techniques and perioperative management, the potential complications accompanying liver resections may further shorten the already limited lifetime of patients with metastatic EC, especially when extended hepatectomies are required in order to achieve an R0-resection status [6]. In patients with liver metastases from gastric and oesophageal cancer, posthepatectomy complications were found to be an independent predictor of poor overall survival [27]. In some cases, the required extent of liver resection is being underestimated in the preoperative radiographic imaging [26]. In accordance with the principle ‘primum non nocere’, a relevant number of planned ECLM resections may have to be abandoned after surgical exploration if the resection of ECLM would require more extended hepatectomies. Alternatively, surgical and interventional approaches such as radiofrequency ablation or microwave ablation can be combined in order to avoid major liver resections [4]. In this context, high-quality imaging (i.e. MRI with liver-specific contrast and diffusion weighting) is of vital concernment in order to develop a thorough multimodal treatment plan in patients with ECLM [37, 38].

A tool similar to the one developed by Blank and colleagues for patients with metastatic gastric and oesophagogastric junction cancer may help to identify patients that could benefit from ECLM resection [39]. The score defines a low-risk group according to tumour differentiation, histopathological response to prior chemotherapy, and (anticipated) resection status (complete vs. incomplete resection). Patients in the low-risk group (n = 22) had a significantly improved median survival of 35.3 months and a 3-year OS of 47.6% compared to 12.0 months and a 3-year OS of 14.2% in the high-risk group (n = 126).

There is further evidence that may favour surgery in patients with limited metastatic disease from oesophageal AC. The AIO-FLOT 3 trial evaluated the outcomes in patients with limited metastatic gastric or EGJ cancer, who received chemotherapy followed by surgical resection [40]. Out of the 67 patients with limited metastatic disease, 36 (60%) proceeded to surgery. The median OS was 31.3 months for patients who underwent surgery compared to 15.9 months for patients that received a non-surgical treatment. A limitation of these results is the lack of randomization for the patients with limited metastatic disease in the group receiving surgery vs chemotherapy only. To address this issue, the RENAISSANCE (AIO-FLOT 5) Trial as a prospective, multicentre phase III trial is currently recruiting patients with the aim to compare these two groups in a randomized manner [41]. Whether these findings can be adopted for ECLM will require further prospective studies, although a comparable outcome for distal oesophageal adenocarcinoma seems to suggest itself because of its molecular similarity with gastric cancer [42]. However, a transferability of the results to liver metastases deriving from oesophageal SCC is problematic as oesophageal SCCs seem to have a different tumour biology and differences in lymphatic spread compared to adenocarcinomas [42,43,44]. Therefore, ECLM from SCC and AC should be separately evaluated.

Conclusion

The available literature is limited and does not facilitate definite conclusions as to whether the resection of ECLM should be standard practice as part of the multimodal treatment concept in metastatic oesophageal cancer. Notwithstanding this, there is enough evidence to justify further studies to identify those select patients with a favourable tumour biology who may benefit from such treatment approaches, especially in the light of emerging immunotherapies.

References

Van Hagen P, Hulshof MC, van Lanschot JJ, Steyerberg EW, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Wijnhoven BP, Richel DJ, Nieuwenhuijzen GA, Hospers GA, Bonenkamp JJ, Cuesta MA, Blaisse RJ, Busch OR, ten Kate FJ, Creemers GJ, Punt CJ, Plukker JT, Verheul HM, SpillenaarBilgen EJ, van Dekken H, van der Sangen MJ, Rozema T, Biermann K, Beukema JC, Piet AH, van Rij CM, Reinders JG, Tilanus HW, van der Gaast A, CROSS Group (2012) Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med 366:2074–2084. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1112088 (PMID: 22646630)

Donlon NE, Ravi N, King S, Cunninhgam M, Cuffe S, Lowery M, Wall C, Hughes N, Muldoon C, Ryan C, Moore J, O’Farrell C, Gorry C, Duff AM, Enright C, Nugent TS, Elliot JA, Donohoe CL, Reynolds JV (2021) Modern oncological and operative outcomes in oesophageal cancer: the St. James’s hospital experience. Ir J Med Sci 190:297–305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-020-02321-4 (PMID: 32696244)

Janmaat VT, Steyerberg EW, van der Gaast A, Mathijssen RH, Bruno MJ, Peppelenbosch MP, Kuipers EJ, Spaander MC (2017) Palliative chemotherapy and targeted therapies for esophageal and gastroesophageal junction cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 11:004063. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004063.pub4 (PMID: 29182797)

Procopio F, Marano S, Gentile D, Da Roit A, Basato S, Riva P, De Vita F, Torzilli G, Castoro C (2019) Management of liver oligometastatic esophageal cancer: overview and critical analysis of the different loco-regional treatments. Cancers (Basel) 12:20. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12010020 (PMID: 31861604)

Seesing MFJ, van der Veen A, Brenkman HJF, Stockmann HBAC, Nieuwenhuijzen GAP, Rosman C, van den Wildenberg FJH, van Berge Henegouwen MI, van Duijvendijk P, Wijnhoven BPL, Stoot JHMB, Lacle M, Ruurda JP, van Hillegersberg R, Gastroesophageal Metastasectomy Group (2019) Resection of hepatic and pulmonary metastasis from metastatic esophageal and gastric cancer: a nationwide study. Dis Esophagus 32:doz034. https://doi.org/10.1093/dote/doz034 (PMID: 31220859)

Filmann N, Walter D, Schadde E, Bruns C, Keck T, Lang H, Oldhafer K, Schlitt HJ, Schön MR, Herrmann E, Bechstein WO, Schnitzbauer AA (2019) Mortality after liver surgery in Germany. Br J Surg 106:1523–1529. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11236 (PMID: 31339558)

Farges O, Goutte N, Bendersky N, Falissard B, ACHBT-French Hepatectomy Study Group (2012) Incidence and risks of liver resection: an all-inclusive French nationwide study. Ann Surg 256:697–704. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e31827241d5 (discussion 704-5 PMID: 23095612)

Angelsen JH, Horn A, Sorbye H, Eide GE, Løes IM, Viste A (2017) Population-based study on resection rates and survival in patients with colorectal liver metastasis in Norway. Br J Surg 104:580–589. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.10457 (PMID: 28181674)

Abdalla EK, Vauthey JN, Ellis LM, Ellis V, Pollock R, Broglio KR, Hess K, Curley SA (2004) Recurrence and outcomes following hepatic resection, radiofrequency ablation, and combined resection/ablation for colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg 239:818–25 (discussion 825-7 [PMID: 15166961 00000658-200406000-00009])

Fernandez FG, Drebin JA, Linehan DC, Dehdashti F, Siegel BA, Strasberg SM (2004) Five-year survival after resection of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer in patients screened by positron emission tomography with F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG-PET). Ann Surg 240:438–47 (discussion 447-50 [PMID: 15319715 00000658-200409000-00005])

Ichida H, Imamura H, Yoshimoto J, Sugo H, Kajiyama Y, Tsurumaru M, Suzuki K, Ishizaki Y, Kawasaki S (2013) Pattern of postoperative recurrence and hepatic and/or pulmonary resection for liver and/or lung metastases from esophageal carcinoma. World J Surg 37:398–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-012-1830-7 (PMID: 23142988)

Huddy JR, Thomas RL, Worthington TR, Karanjia ND (2015) Liver metastases from esophageal carcinoma: is there a role for surgical resection? Dis Esophagus 28:483–487. https://doi.org/10.1111/dote.12233 (PMID: 24898890)

Van Daele E, Scuderi V, Pape E, Van de Putte D, Varin O, Van Nieuwenhove Y, Ceelen W, Troisi R, Pattyn P (2018) Long-term survival after multimodality therapy including surgery for metastatic esophageal cancer. Acta Chir Belg 118:227–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/00015458.2017.1411557 (PMID: 29258384)

Tanaka T, Fujita H, Matono S, Nagano T, Nishimura K, Murata K, Shirouzu K, Suzuki G, Hayabuchi N, Yamana H (2010) Outcomes of multimodality therapy for stage IVB esophageal cancer with distant organ metastasis (M1-Org). Dis Esophagus 23:646–651. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2050.2010.01069.x (PMID: 20545979)

Schauer M, Stein H, Lordick F, Feith M, Theisen J, Siewert JR (2008) Results of a multimodal therapy in patients with stage IV Barrett’s adenocarcinoma. World J Surg 32:2655–2660. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-008-9722-6 (PMID: 18802733)

Nordlinger B, Sorbye H, Glimelius B, Poston GJ, Schlag PM, Rougier P, Bechstein WO, Primrose JN, Walpole ET, Finch-Jones M, Jaeck D, Mirza D, Parks RW, Mauer M, Tanis E, Van Cutsem E, Scheithauer W, Gruenberger T, EORTC Gastro-Intestinal Tract Cancer Group, Cancer Research UK, ArbeitsgruppeLebermetastasen und–tumoren in der ChirurgischenArbeitsgemeinschaftOnkologie (ALM-CAO), Australasian Gastro-Intestinal Trials Group (AGITG), Fédération Francophone de Cancérologie Digestive (FFCD) (2013) Perioperative FOLFOX4 chemotherapy and surgery versus surgery alone for resectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer (EORTC 40983): long-term results of a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 14:1208–1215 ([PMID: 24120480 S1470-2045(13)70447-9])

Fairweather M, Swanson R, Wang J, Brais LK, Dutton T, Kulke MH, Clancy TE (2017) Management of neuroendocrine tumor liver metastases: long-term outcomes and prognostic factors from a large prospective database. Ann Surg Oncol 24:2319–2325. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-017-5839-x (PMID: 28303430)

Adam R, Chiche L, Aloia T, Elias D, Salmon R, Rivoire M, Jaeck D, Saric J, Le Treut YP, Belghiti J, Mantion G, Mentha G, Association Française de Chirurgie (2006) Hepatic resection for noncolorectal nonendocrine liver metastases: analysis of 1,452 patients and development of a prognostic model. Ann Surg 244:524–535 ([PMID: 16998361 00000658-200610000-00007])

Weitz J, Blumgart LH, Fong Y, Jarnagin WR, D’Angelica M, Harrison LE, DeMatteo RP (2005) Partial hepatectomy for metastases from noncolorectal, nonneuroendocrine carcinoma. Ann Surg 241:269–276 ([PMID: 15650637 00000658-200502000-00012])

Gandy RC, Bergamin PA, Haghighi KS (2017) Hepatic resection of non-colorectal non-endocrine liver metastases. ANZ J Surg 87:810–814. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.13470 (PMID: 27037839)

Slotta JE, Schuld J, Distler S, Richter S, Schilling MK, Kollmar O (2014) Hepatic resection of non-colorectal and non-neuroendocrine liver metastases - survival benefit for patients with non-gastrointestinal primary cancers - a case-controlled study. Int J Surg 12:163–168 ([PMID: 24342081 S1743-9191(13)01124-2])

Fitzgerald TL, Brinkley J, Banks S, Vohra N, Englert ZP, Zervos EE (2014) The benefits of liver resection for non-colorectal, non-neuroendocrine liver metastases: a systematic review. Langenbecks Arch Surg 399:989–1000. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-014-1241-3 (PMID: 25148767)

Bresadola V, Rossetto A, Adani GL, Baccarani U, Lorenzin D, Favero A, Bresadola F (2011) Liver resection for noncolorectal and nonneuroendocrine metastases: results of a study on 56 patients at a single institution. Tumori 97:316–322. https://doi.org/10.1700/912.10028 (PMID: 21789009)

Carmona-Bayonas A, Jiménez-Fonseca P, Echavarria I, Sánchez Cánovas M, Aguado G, Gallego J, Custodio A, Hernández R, Viudez A, Cano JM, AGAMENON Study Group (2018) Surgery for metastases for esophageal-gastric cancer in the real world: data from the AGAMENON national registry. Eur J Surg Oncol 44:1191–1198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2018.03.019 (PMID: 29685755)

Schmidt T, Alldinger I, Blank S, Klose J, Springfeld C, Dreikhausen L, Weichert W, Grenacher L, Bruckner T, Lordick F, Ulrich A, Büchler MW, Ott K (2015) Surgery in oesophago-gastric cancer with metastatic disease: treatment, prognosis and preoperative patient selection. Eur J Surg Oncol 41:1340–1347 ([PMID: 26213358 S0748-7983(15)00436-9])

Badgwell B, Roy-Chowdhuri S, Chiang YJ, Matamoros A, Blum M, Fournier K, Mansfield P, Ajani J (2015) Long-term survival in patients with metastatic gastric and gastroesophageal cancer treated with surgery. J Surg Oncol 111:875–881. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.23907 (PMID: 25872485)

Andreou A, Viganò L, Zimmitti G, Seehofer D, Dreyer M, Pascher A, Bahra M, Schoening W, Schmitz V, Thuss-Patience PC, Denecke T, Puhl G, Vauthey JN, Neuhaus P, Capussotti L, Pratschke J, Schmidt SC (2014) Response to preoperative chemotherapy predicts survival in patients undergoing hepatectomy for liver metastases from gastric and esophageal cancer. J Gastrointest Surg 18:1974–1986. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-014-2623-0 (PMID: 25159501)

Depypere L, Lerut T, Moons J, Coosemans W, Decker G, Van Veer H, De Leyn P, Nafteux P (2017) Isolated local recurrence or solitary solid organ metastasis after esophagectomy for cancer is not the end of the road. Dis Esophagus 30:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/dote.12508 (PMID: 27704661)

Parry K, Visser E, van Rossum PS, Mohammad NH, Ruurda JP, van Hillegersberg R (2015) Prognosis and treatment after diagnosis of recurrent esophageal carcinoma following esophagectomy with curative intent. Ann Surg Oncol 22(Suppl 3):S1292-300. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-015-4840-5 (PMID: 26334295)

Ichikawa H, Kosugi S, Nakagawa S, Kanda T, Tsuchida M, Koike T, Tanaka O, Hatakeyama K (2011) Operative treatment for metachronous pulmonary metastasis from esophageal carcinoma. Surgery 149:164–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2010.07.047 (PMID: 20817205)

Kanamori J, Aokage K, Hishida T, Yoshida J, Tsuboi M, Fujita T, Nagino M, Daiko H (2017) The role of pulmonary resection in tumors metastatic from esophageal carcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol 47:25–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyw141 (PMID: 27655907)

Wang J, Suri JS, Allen PK, Liao Z, Komaki R, Ho L, Hofstetter WL, Lin SH (2016) Factors predictive of improved outcomes with multimodality local therapy after palliative chemotherapy for stage IV esophageal cancer. Am J Clin Oncol 39:228–235. https://doi.org/10.1097/COC.0000000000000066 (PMID: 24710122)

Liu J, Wei Z, Wang Y, Xia Z, Zhao G (2018) Hepatic resection for post-operative solitary liver metastasis from oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. ANZ J Surg 88:E252–E256. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.13810 (PMID: 27764891)

Kobayashi N, Kohno T, Haruta S, Fujimori S, Shinohara H, Ueno M, Udagawa H (2014) Pulmonary metastasectomy secondary to esophageal carcinoma: long-term survival and prognostic factors. Ann Surg Oncol 21(Suppl 3):S365-9. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-014-3677-7 (PMID: 24796966)

Shiono S, Kawamura M, Sato T, Nakagawa K, Nakajima J, Yoshino I, Ikeda N, Horio H, Akiyama H, Kobayashi K, Metastatic Lung Tumor Study Group of Japan (2008) Disease-free interval length correlates to prognosis of patients who underwent metastasectomy for esophageal lung metastases. J Thorac Oncol 3:1046–1049. https://doi.org/10.1097/JTO.0b013e318183aa0c (PMID: 18758309)

Chao YK, Wu YC, Liu YH, Tseng CK, Chang HK, Hsieh MJ, Chu Y, Liu HP (2010) Distant nodal metastases from intrathoracic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: characteristics of long-term survivors after chemoradiotherapy. J Surg Oncol 102:158–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.21588 (PMID: 20648587)

DeSouza NM, Liu Y, Chiti A, Oprea-Lager D, Gebhart G, Van Beers BE, Herrmann K, Lecouvet FE (2018) Strategies and technical challenges for imaging oligometastatic disease: recommendations from the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer imaging group. Eur J Cancer 91:153–163 ([PMID: 29331524 S0959-8049(17)31491-0])

Taouli B, Koh DM (2010) Diffusion-weighted MR imaging of the liver. Radiology 254:47–66. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.09090021 (PMID: 20032142)

Blank S, Lordick F, Dobritz M, Grenacher L, Burian M, Langer R, Roth W, Schaible A, Becker K, Bläker H, Sisic L, Stange A, Compani P, Schulze-Bergkamen H, Jäger D, Büchler M, Siewert JR, Ott K (2013) A reliable risk score for stage IV esophagogastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 39:823–830 ([PMID: 23375470 S0748-7983(13)00007-3])

Al-Batran SE, Homann N, Pauligk C, Illerhaus G, Martens UM, Stoehlmacher J, Schmalenberg H, Luley KB, Prasnikar N, Egger M, Probst S, Messmann H, Moehler M, Fischbach W, Hartmann JT, Mayer F, Höffkes HG, Koenigsmann M, Arnold D, Kraus TW, Grimm K, Berkhoff S, Post S, Jäger E, Bechstein W, Ronellenfitsch U, Mönig S, Hofheinz RD (2017) Effect of neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgical resection on survival in patients with limited metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer: the AIO-FLOT3 trial. JAMA Oncol 3:1237–1244. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0515 (PMID: 28448662)

Al-Batran SE, Goetze TO, Mueller DW, Vogel A, Winkler M, Lorenzen S, Novotny A, Pauligk C, Homann N, Jungbluth T, Reissfelder C, Caca K, Retter S, Horndasch E, Gumpp J, Bolling C, Fuchs KH, Blau W, Padberg W, Pohl M, Wunsch A, Michl P, Mannes F, Schwarzbach M, Schmalenberg H, Hohaus M, Scholz C, Benckert C, Knorrenschild JR, Kanngießer V, Zander T, Alakus H, Hofheinz RD, Roedel C, Shah MA, Sasako M, Lorenz D, Izbicki J, Bechstein WO, Lang H, Moenig SP (2017) The RENAISSANCE (AIO-FLOT5) trial: effect of chemotherapy alone vs. chemotherapy followed by surgical resection on survival and quality of life in patients with limited-metastatic adenocarcinoma of the stomach or esophagogastric junction - a phase III trial of the German AIO/CAO-V/CAOGI. BMC Cancer 17:893. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-017-3918-9 (PMID: 29282088)

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (2017) Integrated genomic characterization of oesophageal carcinoma. Nature 541:169–175. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature20805 (PMID: 28052061)

Siewert JR, Stein HJ, Feith M, Bruecher BL, Bartels H, Fink U (2001) Histologic tumor type is an independent prognostic parameter in esophageal cancer: lessons from more than 1,000 consecutive resections at a single center in the Western world. Ann Surg 234:360–7 (discussion 368-9 [PMID: 11524589 0000658-200109000-00010])

Stein HJ, Feith M, Bruecher BL, Naehrig J, Sarbia M, Siewert JR (2005) Early esophageal cancer: pattern of lymphatic spread and prognostic factors for long-term survival after surgical resection. Ann Surg 242:566–73 (discussion 573-5 [PMID: 16192817 00000658-200510000-00012])

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Andreas RR Weiss, Noel E Donlon, and Christina Hackl developed the conception and design of the study. Andreas RR Weiss performed the literature search and data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. Noel E Donlon, Hans J Schlitt, and Christina Hackl critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Weiss, A.R.R., Donlon, N.E., Schlitt, H.J. et al. Resection of oesophageal and oesophagogastric junction cancer liver metastases — a summary of current evidence. Langenbecks Arch Surg 407, 947–955 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-021-02387-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-021-02387-3